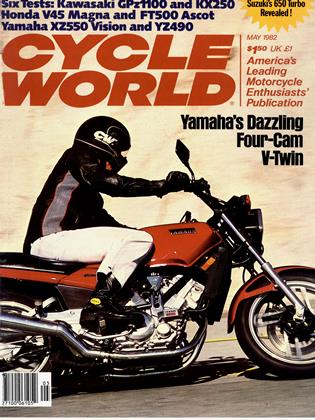

YAMAHA XZ550 VISION

CYCLE WORLD TEST

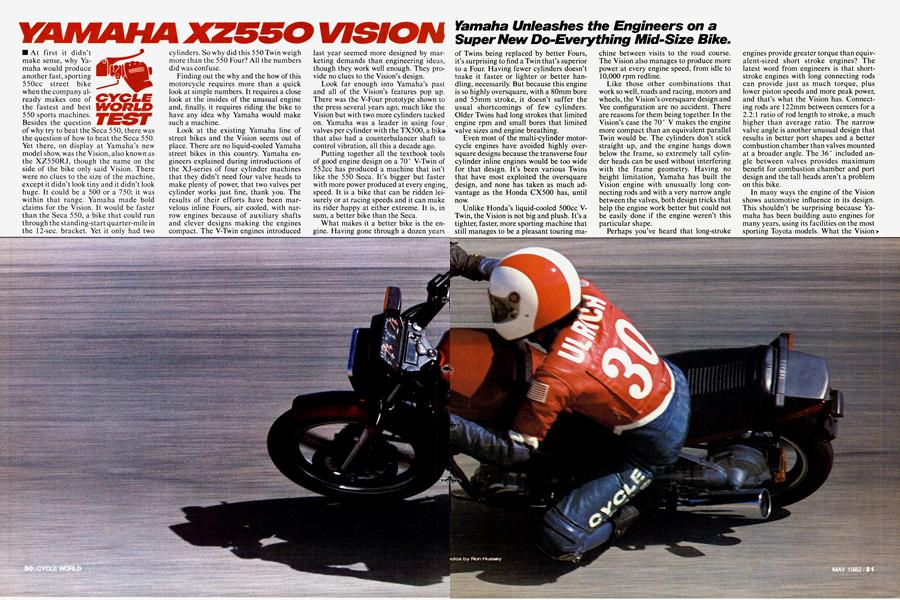

At first it didn't make sense, why Yamaha would produce another fast, sporting 550cc street bike when the company already makes one of the fastest and best 550 sports machines. Besides the question of why try to beat the Seca 550, there was the question of how to beat the Seca 550. Yet there, on display at Yamaha's new model show, was the Vision, also known as the XZ55ORJ, though the name on the side of the bike only said Vision. There were no clues to the size of the machine, except it didn't look tiny and it didn't look huge. It could be a 500 or a 750; it was within that range. Yamaha made bold claims for the Vision. It would be faster than the Seca 550, a bike that could run through the standing-start quarter-mile in the 12-sec. bracket. Yet it only had two cylinders. So why did this 550 Twin weigh more than the 550 Four? All the numbers did was confuse.

Finding out the why and the how of this motorcycle requires more than a quick look at simple numbers. It requires a close look at the insides of the unusual engine and, finally, it requires riding the bike to have any idea why Yamaha would make such a machine.

Look at the existing Yamaha line of street bikes and the Vision seems out of place. There are no liquid-cooled Yamaha street bikes in this country. Yamaha engineers explained during introductions of the XJ-series of four cylinder machines that they didn’t need four valve heads to make plenty of power, that two valves per cylinder works just fine, thank you. The results of their efforts have been marvelous inline Fours, air cooled, with narrow engines because of auxiliary shafts and clever designs making the engines compact. The V-Twin engines introduced

last year seemed more designed by marketing demands than engineering ideas, though they work well enough. They provide no clues to the Vision’s design.

Look far enough into Yamaha’s past and all of the Vision’s features pop up. There was the V-Four prototype shown to ' the press several years ago, much like the Vision but with two more cylinders tacked on. Yamaha was a leader in using four valves per cylinder with the TX500, a biksr that also had a counterbalancer shaft to control vibration, all this a decade ago.

Putting together all the textbook tools of good engine design on a 70° V-Twin of 552cc has produced a machine that isn’t like the 550 Seca. It’s bigger but faster with more power produced at every engine, speed. It is a bike that can be ridden leisurely or at racing speeds and it can make its rider happy at either extreme. It is, in sum, a better bike than the Seca.

What makes it a better bike is the engine. Having gone through a dozen years of Twins being replaced by better Fours, it’s surprising to find a Twin that’s superior to a Four. Having fewer cylinders doesn’t tnake it faster or lighter or better handling, necessarily. But because this engine is so highly oversquare, with a 80mm bore and 55mm stroke, it doesn’t suffer the usual shortcomings of few cylinders. Older Twins had long strokes that limited engine rpm and small bores that limited valve sizes and engine breathing.

Even most of the multi-cylinder motorcycle engines have avoided highly oversquare designs because the transverse four cylinder inline engines would be too wide for that design. It’s been various Twins that have most exploited the oversquare design, and none has taken as much advantage as the Honda CX500 has, until now.

Unlike Honda’s liquid-cooled 500cc VTwin, the Vision is not big and plush. It’s a tighter, faster, more sporting machine that still manages to be a pleasant touring machine between visits to the road course. The Vision also manages to produce more power at every engine speed, from idle to 10,000 rpm redline.

Like those other combinations that work so well, roads and racing, motors and wheels, the Vision’s oversquare design and Vee configuration are no accident. There are reasons for them being together. In the Vision’s case the 70° V makes the engine more compact than an equivalent parallel Twin would be. The cylinders don’t stick straight up, and the engine hangs down below the frame, so extremely tall cylinder heads can be used without interfering with the frame geometry. Having no height limitation, Yamaha has built the Vision engine with unusually long connecting rods and with a very narrow angle between the valves, both design tricks that help the engine work better but could not be easily done if the engine weren’t this particular shape.

Perhaps you’ve heard that long-stroke engines provide greater torque than equivalent-sized short stroke engines? The latest word from engineers is that shortstroke engines with long connecting rods can provide just as much torque, plus lower piston speeds and more peak power, and that’s what the Vision has. Connecting rods are 122mm between centers for a 2.2:1 ratio of rod length to stroke, a much higher than average ratio. The narrow valve angle is another unusual design that results in better port shapes and a better combustion chamber than valves mounted at a broader angle. The 36° included angle between valves provides maximum benefit for combustion chamber and port design and the tall heads aren’t a problem on this bike.

In many ways the engine of the Vision shows automotive influence in its design. This shouldn’t be surprising because Yamaha has been building auto engines for many years, using its facilities on the most sporting Toyota models. What the Vision» does not copy are Yamaha’s existing VTwins, the XV750 and XV920. The only similarity to the existing designs is in the cam drive, which uses anti-lash sprockets on each end of the crank to drive the overhead cams. The layout is the same, though no parts are interchangeable.

Yamaha Unleashes the Engineers on a Super New Do-Everything Mid-Size Bike.

At its most basic characteristics, the new Yamaha is different than the previous V-Twin. They don’t even rotate the same direction. Last year the air-cooled V-Twins came out with engines that spun opposite fhe direction of the bike’s wheels; this counterrotation, Yamaha said, reduces vibration from the 75° V engine. That’s why the Virago and XV920 didn’t need any counterbalancer shaft, explained Yamaha. Now there’s a 70° liquid-cooled VTwin Yamaha with the engine spinning the same direction as the bike’s wheels, equipped with a counterrotating balancer shaft and it’s mounted in an entirely different steel tube frame. And, just like the

last V-Twins from Yamaha, this new engine works.

If anything, the new V-Twin works better than its big brothers. It was designed to produce more power for its size than the larger V-Twins. Those bigger machines weren’t designed to compete head-to-head with the fastest 750s and 900s in terms of performance, so they didn’t have to be tuned so highly. The Vision is not afforded that luxury. Yamaha decided the Vision would compete directly with any four-cylinder machine for performance and the differences between the Virago-style engine and the Vision engine are there to support more peak power.

The first key to more power is higher engine speed. The larger V-Twins only needed a 7000 rpm limit for adequate power. That lower engine speed meant they could be balanced for a narrower rpm band and didn’t need the counterbalancer shaft. For the Vision, maintaining a smooth-running engine over a very wide rpm band meant the addition of the geardriven counterbalancer. Vibration forces increase dramatically with increased en-

gine speed and, even though the Vision engine is smaller than the Virago engine, the 10,000 rpm redline makes the counterbalancer a useful addition. Mounted at the front of the engine, forward of the crankshaft, it is driven by a spring-cushioned straight-cut gear. Its 25mm shaft diameter spins in large ball bearings at both sides of the vertically-split cases.

At the ends of the massive crankshaft are full-circle plain bearings. Because the cases are not split horizontally, the Yamaha has one-piece main bearings that are pressed into the cases. Machined surfaces on the inside of the cases act as the thrust bearings. The bottom end, like the rest of the Vision engine, looks big and strong. Main bearings carry a 45mm shaft. Connecting rod big ends are 45mm, the small ends 20mm. The rods ride sideby-side on the single throw crank, the forward cylinder being mounted on the righthand side. At the top of the connecting* rods are 80mm pistons, with slight rise and cut-outs in the top for four valves. There is little unusual about the cast aluminum pistons, the top ring being coated, the sec-

ond compression ring being a taper and the oil control a three-piece ring.

Power is transmitted from the one-piece crankshaft to the multi-plate clutch by straight-cut gears. The clutch is normal Yamaha, with eight plates and a wave washer to smooth engagement. It is located on the righthand side of the transmission mainshaft, which rides on large ball bearings.

There are no auxiliary or extra shafts in the Vision. The transmission consists of the mainshaft and the countershaft. The driveshaft takes its power from the lefthand end of the countershaft through bevel gears. Because the engine spins in the conventional direction, that is clockwise when viewed from the righthand side, the driveshaft connects to the forward side of the countershaft’s beveled gear. It would also be possible to take power off the aft-side of the countershaft’s bevel "gear and spin the engine backwards, as Honda is doing on its V-Fours, but either way seems to work well.

From the bevel gears power runs through a small U-joint and back to the

driveshaft in the lefthand side of the swing arm. This is a different swing arm than that on the Virago and uses a spring loaded ramp-type shock absorber at the end of the driveshaft, just ahead of the ring and pinion.

All the gears in the Vision’s engine are straight-cut. The starter operates through an idler gear to the generator flywheel. At the other end of the crankshaft there are nylon gears to operate the water pump and other small spur gears spinning the oil pump. The water pump has a small plastic impeller and ceramic seals. It pulls coolant from the bottom of the aluminum radiator and pushes it out through a pair of chromed steel tubes, one running to each cylinder. Coolant runs around the steel-lined aluminum cylinder and up through the cylinder head, where it runs back to the radiator.

While the bottom end is strong, compact and relatively simple, the top end of the Vision is what makes all the power. It does so with lots of big valves spending as much of their lives open as possible and with big, straight ports and little restric-

tion in the exhaust or intake.

Because the Vision engine is highly oversquare there is lots of room for valves in the pentroof combustion chambers. Yamaha has made the most of this with a pair of 31 mm intake valves and a pair of 26mm exhaust valves in each cylinder. To put this in perspective, the valve sizes on the Kawasaki GPz550 are 27mm intake and 24mm exhaust and there are the same number of valves in the four-cylinder Kawasaki as there are in the two-cylinder Yamaha. On valve sizes alone the Vision has a breathing advantage on its four-cylinder competition, a trick not often available to a Twin. In addition the Vision makes more of its bigger valves by using abnormally sporting cams.

Duration of the intake cams in the Vision is 284 °, exhaust cams are 276 °. Overlap is 70° and lift is 8.8mm for intake and 8.3mm for exhaust. These numbers are more extreme than those of the cams used in a GPz550 or a Yamaha Seca 550, for instance. Duration is longer, overlap is greater and valve lift is higher, all contributing to more peak power because the >

valves open farther, longer, enabling more air to flow through the Vision’s engine. The next closest 550-class bike to the Vision for radical cam timing and valve area is Yamaha’s own Seca 550 with 268° and 264° cam duration, 30 and 26mm valves and 7.8 and 7.1 mm valve lift. That was the target the Vision engineers had to aim at and they hit it.

Because the overlap is so great, a high 10.5:1 compression ratio could be used without excessive compression pressure leading to preignition. Performance cams require high compression, generally, and this one has it.

Besides the extreme cam timing, the valve train is noteworthy for several other features. Cam followers are normal inverted buckets, with the shims installed at the top of the buckets, just under the cams. To hold noise to a minimum clearance between the bucket and the shims is reduced from that on normal Yamahas with bucket-and-shim valve opening. Valve stems are slim at 6mm, another feature reducing interference in the ports. The cams are the same on the front and rear cylinders. To time the cams there are cam sprockets with four holes, each hole being used on a different cam. This way only one sprocket has to be produced. The cams ride directly in the aluminum head and the cam cap. But each cam holding cap has a rubber plug in it. Remove the plug and there’s a hole in the cap. Turn the cams to the right position and there are holes through each end of each cam. The purpose of all these holes is to provide access to the headbolts. A long 8mm alien wrench can fit through the caps, cams and heads to the deeply-inset headbolts. There may have been other ways for Yamaha to fasten the head onto the cylinder, but this is a clean, convenient system.

Silent link-plate chains drive the cams and are tensioned by slippers and automatic tensioners. Instead of the common ramp-type automatic adjuster, the Vision uses an adjuster with a serrated plunger held in place by a locking lever. This type of adjuster is more resistant to backing out at high rpm.

Two large exhaust ports in each head connect to twin header pipes, which connect in the exhaust system before branching out into two mufflers. The length of exhaust systems on the front and back cylinders is much different, the forward cylinder using long double tubes wrapping under the engine, the back cylinder having a short branched exhaust.

In the center of the V is the intake system. The carburetors are unusual for a motorcycle, being a pair of downdraft, butterfly-throttle automotive-type carbs. There are accelerator pumps and an enrichening choke circuit, plus a vacuum-

operated fuel pump mounted between the two carbs. Each carb has a 36mm barrel, leading through a short tube to the intake port that branches apart to the two intake valves. Because the liquid-cooled engine shouldn’t have a different operating temperature for the two cylinders, it is surprising to find different main jets in the two carbs. The rear carb has a one size larger main jet, apparently due to the differences in exhaust flow.

Remember the radical cam timing? Normally a motorcycle would suffer poor low speed throttle response and power from such cam timing in exchange for the increase in peak power. To compensate for that the Vision has Yamaha’s Intake Control System, a small plastic chamber that connects to the intake port. This type of intake reservoir was first used on Yamaha’s dirt bikes to good effect and now comes to street bikes. It is a simple system, with a small hose connecting a two-chambered plastic container to the intake port of one intake valve on each head. Having the YICS connect to just one of the two intake valves provides a sw irl to the incoming mixture as the waves of air pressure flow in and out of the plastic chamber, improving combustion efficiency at low speeds. What makes this system work is an absurdly simple little plastic container. It’s that small gray triangle on the righthand side of the bike beside the carbs. It

only weighs a couple of ounces. It has no moving parts. But pull it off and plug the holes and the Vision doesn’t run as well at low engine speeds, so there must be something to it.

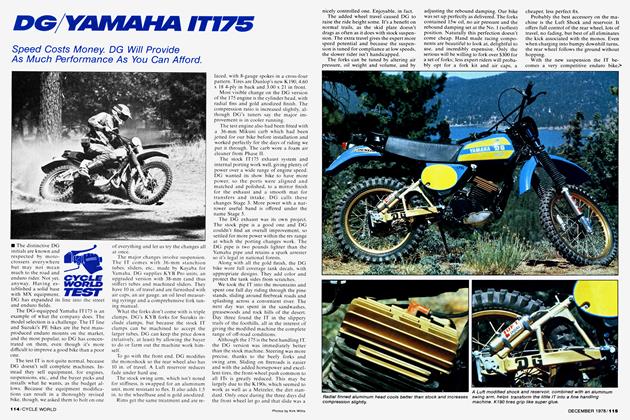

How this engine is carried in the motorcycle is just as novel as the plastic box or the downdraft carbs. Until now motorcycle frames could be a full cradle tube frame, a stressed engine tube frame or a pressed steel backbone, usually with a stressed engine. The Vision has a welded steel tube frame, but it’s not a cradle type. There are no downtubes and there are no tubes under the engine. Instead, the steer-^ ing head is fastened to a pair of top tubes and a pair of bottom tubes. The top tubes branch out to the sides and angle down towards the rear axle. The bottom tubes also splay out, but they do not angle down very much, wrapping around the sides of the engine before bending back. Onto the back of this frame attaches the braced" swing arm. Like the monoshock suspension on Yamaha’s early motocross bikes, the top brace of the swing arm pushes against a single shock mounted high in the frame, where it fastens to the top frame tubes under the seat.

Look at the photos of the frame and itlooks simple. There’s a lot of good thinking in this frame, too. Loads from the rear suspension are fed directly into the backbone. It’s virtually a straight line from the

rear axle through the swing arm, the rear shock, the frame and up to the steering head. Next, the distance from the top frame tubes to the lower frame tubes is very short. This adds to strength and rigidity. The engine hangs from this frame, feeding its torque and stresses into the swing arm pivot plate on the frame *and attached to the lower frame tubes at the center of the Vee, right at the base of the cylinders. This narrow engine can be mounted at the lowest possible position without forcing the frame out of shape. Engine removal is made easier by a removable lower righthand frame tube. It -unbolts at the front and back not only for engine removal, but for some engine service tasks.

On the front of this frame hangs the aluminum radiator and its electric fan. Where the radiator is mounted is important in the Vision’s design. If Yamaha had ëtuck a normal set of straight-leg forks on the Vision frame the legs would have hit the radiator any time the forks were turned more than a few degrees off center. The normal approach would have been to stick the steering head another couple of inches forward, which would have lengthened the wheelbase that much. For the weight and size of this bike Yamaha didn’t want a longer wheelbase. That would have slowed down the steering just that much more. Instead, the Vision has trailing axle

forks. The steering head and the front axle are just where Yamaha wants them to be. The placement provides for the right steering head angle and the proper trail. But there is greater than normal offset to the triple clamps and the axle is behind the fork sliders, so that when the bars are turned to the stops the fork legs don’t hit the radiator. It’s a clever approach to an unusual problem.

Aside from the position of the front axle and the rear suspension unit, the suspension on the Vision is very simple. Fork design is normal telescopic with no adjustment of damping, no air caps and no antidive. Just plain old coil springs and hydraulic damping, doing a good job of keeping the front wheel on the ground and the handlebars controllable.

Just as simple is the rear suspension unit, a single coil spring of variable rate and a non-adjustable damper within that spring. Spring preload can be adjusted to five positions by turning a collar around the shock body. Adjusting the spring preload requires raising the hinged seat first.

Attached to the ends of the suspension are lightweight cast wheels unlike any previous Yamaha wheels. Having spent a year not getting used to the spiral pin-wheel look on most Yamahas, the new wheel looks very good. It uses thin rectangularshaped links between the open-center hub and the rim. It’s the open center that con-

tributes most to the weight reduction of these wheels. The spokes fasten to an open hub, along with the large 11.8 in. single disc. In back the same design includes a drum brake and splines for the shaft drive.

Using a large single disc does not provide as much brake swept area as using two more normal sized discs in front. It is Yamaha’s way to get the best performance with the lowest cost and weight. The engineers back in Japan know they could get better high speed braking power and control with another disc, and that would even braking loads on the front suspension so it didn’t bind when the front brake is applied hard, but those are the compromises they have to make.

An important part of the Vision’s development is in its styling. Yamaha has been perhaps the most active Japanese motorcycle manufacturer in styling. Yamaha Specials began a look that is still with us and that other companies are still copying. Then came the Seca models, extending from the futuristic Seca 750 to the beautifully clean Seca 650. Now the Vision and the new 400 Seca are branching into a different area, with more angles and Vshapes.

Most of the Vision’s styling emphasis comes from the gas tank. It’s a large tank, with a big flat top and a combination of angles forming the sides. There’s a crease in the middle of the tank creating a notice>

able V-shape in the sides. The bottom of this tank is lower than the carburetors, necessitating the vacuum-operated fuel pump. The inner panel of the tank has to provide room for the wide top tubes of the frame and the air filter tucked between the frame tubes, robbing the tank of more capacity. Fortunately this hasn’t kept Yamaha from expanding the tank so it contains a useful supply of fuel, and the styling’s just gravy.

At the back of the tank is a small diamond-shaped cover, leading to the upswept angle of the seat, ending in the wrap-around taillight. By using a moderately sized 18-in. rear tire and the unusual frame, there’s plenty of room for a deep padded seat without raising seat height into the clouds. The slope of the seat is minimal and doesn’t prevent the rider and a passenger from finding a comfortable position.

More angularity is found in the instruments and the rectangular halogen headlight. The box-shaped instrument cluster includes a temperature gauge with the speedometer and tachometer, but doesn’t have any of the more exotic array of sensors and blinking lights, a decision that meets with our approval.

All the various squares and triangles and V-shapes form a tidy and compact motorcycle. Better still, it doesn’t look like anything else. The Vision is distinctive from any angle, with no borrowed shapes or pieces. Many details on the Vision are similarly unusual in design and novel in their own right. Large cast aluminum plates form the footpeg brackets and hold things like brake levers and the mufflers. They are light and simple and fit well on the Vision. Handlebars are another unusual design. There are several multipiece handlebars on motorcycles now, but most of them are add-on designs with lots of parts and no adjustment. On the Vision the aluminum uprights attach to the sides of the top triple clamp, forming part of the clamp. This eliminates an additional handlebar pedestal and makes for an uncluttered top triple clamp, into which is set the ignition switch and several warning lights. And unlike many other new bikes, there is no rubber or plastic cover for this area. At the top of the handlebar uprights are clamps holding the bar ends, which are angled, providing for up-and-down adjustment. The range of adjustment is limited by a pin in the handlebar end, but it’s sufficient to keep most riders content with the riding position. While the handlebar assembly of the Vision is simpler and more adjustable than most, it still doesn’t offer the easy change in handlebar shapes of ordinary tubular handlebars, a feature many riders like.

Positioned in any of the three possible handlebar positions, the bars would be

considered normal. All the other positions and signals from the Vision indicate it falls within that vast middleground of sporting street bikes, looking ready for track use but also being comfortable enough for extended travel.

Riding the Vision demonstrates how wide that middle ground can be. Around town the Vision’s behavior is exemplary. It starts well cold or hot and can be ridden away immediately without hesitation, stalling, surging or dying. Only if the throttle is opened fully at low engine speed can the engine be made to cough or sputter, but without trying to provoke a difficulty, none occurs. The engine is surprisingly torquey. It pulls strongly from idle, with noticeable flywheel effect for getting under way, but no hesitation to rev at any engine speed. Revving the engine with the bike parked produces a medium-loud gear whine from all those straight-cut gears. There’s also a pleasantly subdued exhaust note, but there is no clatter or mechanical noises besides the whir of gears. That gear noise disappears on the road as the exhaust note becomes the only sound from the motorcycle that a rider can hear. It’s a pleasant sound, a bit too muffled to please some ears, but a healthy and sporting note.

Hold the throttle open a little longer between shifts and the engine just keeps on pulling, harder and harder, with no flat spots anywhere. Peak power is produced at 9500 rpm and there is a slight drop in power beyond this, as the tach climbs to the 10,000 rpm redline, but the engine is happy to keep spinning until the needle is well past the redline. This isn’t a two-stage kind of power, but there is enough power at all engine speeds so it can be ridden gently or thrashed on a track and feel like a high performance machine all the time.

Controls on the Vision are particularly light and convenient. The butterfly-throttle carburetors need only light return springs, so the throttle is easy to turn and smooth. The clutch pull is similarly light, engagement is positive and it releases fully, with none of the slight clutch drag common to some Yamahas.

Excellent engine smoothness makes the Vision pleasant on the highway. The counterbalancer cancels the imbalance of the crank and manages to work effectively at every engine speed. What it doesn’t cancel is the pulse of the engine that results from the power pulses. Being a Twin, there are half as many impulses as a Four would have at the same engine speed and it is this reduced frequency of impulse that eliminates the buzz that occurs in most high revving Fours. This smooth running engine doesn’t have as noticeable a smooth spot as many Fours, which makes judging engine speed almost impossible without the tach. As nice as the smooth-running engine is, some riders lamented the lack of Twin feel in the Vision. Not having the usual V-Twin stagger is one reason why the Vision was thought of as a mid-size bike,

or a sport bike than it was thought of as a Twin.

Handling is as strong as the engine per formance. For the past several years Jap anese sport bikes have progressed from questionable to competent in handling as frames have been strengthened and suspension has become more controlled. The vision’s contemporaries are noteworthy for their absence of handling flaws, most of them possessing good cornering clearance and an admirable resistance to wobbles under most circumstances. The Vision goes these bikes one better. It isn’t just that it has nothing wrong, but that it offers positive characteristics that help a rider.,,.

Instead of compensating for the machine’s flaws, the Vision rider gets to apply the machine’s strengths, and nowhere is this more evident than at a racetrack. Taking off from a start the Vision is a match for the best in class, though it’s not going to beat those fast red bikes to the first corner. With its single front disc brake, the Vision doesn’t look like it could match the braking power of the double front discequipped bikes. Yet on the track riders would begin laps braking at normal points and find themselves going too slowly through turns, with lots of cornering clearance left and lots of room for more speech With a few laps of practice riders could enter turns much deeper than they could on last year’s Kawasaki GPz550, for instance.

It isn’t that the brakes of the Yamaha

are stronger than the double discs, but that the single disc of the Vision is strong enough and controllable enough not to be a hinderance and the handling of the Vision is markedly superior to competing bikes. Most of the Vision’s racetrack advantage comes from its ability to change directions quickly. That’s what the Vision is designed to do, and it does it well.

This ability to change directions easily and controllably has not cost the Vision any stability. It is provided by the compact engine, mounted low in the frame and reducing the roll inertia of the bike. The Vision does have a steep 26.3 ° steering head »angle, but the 57 in. wheelbase and 4.5 in. of trail aren’t extreme for this size bike, both figures being a bit longer than normal. The Vision’s 462 lb. weight is about average, a good 38 lb. heavier than the Seca 550 but a couple of pounds lighter than the Kawasaki GPz550.

Combining with the ease of steering is precision and excellent cornering clearance. This is particularly valuable in variable radius corners, where slight corrections at the handlebars make instant changes in the bike’s attitude, keeping the Vision on the proper line. Like most Japanese bikes, the Vision is designed to touch down at the pegs first when leaned over far. Unlike anything else in its class, the Vision must be leaned over far more before those pegs scrape. Pipes and pedals and stands are well tucked up out of the way and pose no problem in cornering.

The stock Dunlop tires work well on this bike, not sliding even at extreme angles on average pavement. The Vision’s driveshaft was as benign as the tires on the track, not causing any difficulty or even being noticeable.

Only one part of the test track caused any difficulty for the Vision, that being the fast, bumpy turn eight at Willow Springs. The Vision could be ridden flat out in 5th through eight, but it produced a slight pogo sensation with a lighter rider on board. It didn’t get worse after 100 mi. of racetrack use and it wasn’t difficult to deal with, but some more suspension tuning could probably eliminate this.

Remember that the Vision doesn’t have the fashionable multi-adjustable suspension that many larger bikes have. It has a variable rate coil spring and a damper in the back and forks with no more adjustment than what a change of fork oil can provide. The result is a sporting suspension that works well on the track with a variety of rider sizes aboard. The shortcomings of this suspension are more apparent off the track where the ride can be a bit firmer than some of the competition for one rider and too soft for a rider with passenger. It doesn’t take a very large passenger to make the back end bottom over dips and bumps. The bike isn’t incapable of carrying a passenger, but it also isn’t as adept at load carrying as a larger bike is.

At the other extreme, the Vision can be bouncy on concrete freeways where it

hobby-horses over expansion joints. It could be improved in several areas by a progressive rate suspension or more adjustment, but either of these would cost more money and that is an important consideration on a bike competing against as many other models as this one.

Compensating for a little roughness in the suspension is a seat that is better padded and better shaped than the seats on most bikes this size. It is relatively flat, with no grab strap over it, making it easy for the rider to move around on the saddle during long trips. The excellent seat and smooth motor make the Vision an excellent touring bike even though it doesn’t have the pillow-like suspension of a GL500 Honda, for instance. With its 4.5 gal. gas tank the Vision can easily go 200 mi. between fillups. A rider doesn’t have a difficult time riding that far on the Vision, either. The broad, flat top of the tank makes a good tank bag surface, though the odd handlebars interfere with mounting some kinds of fairings.

How the Vision stacks up against its competition will be concluded after the new single shock GPz550 is tested. Right now it is equal to the fastest 550s for speed and acceleration, superior to anything in its class for handling, and all the time it manages to be as easy to ride and as comfortable as any mid-size machine.

Well done, Yamaha. You’ve managed to make a bike that’s not just different, but different for good reasons. BS

YAMAHA

XZ550RJ

$3099

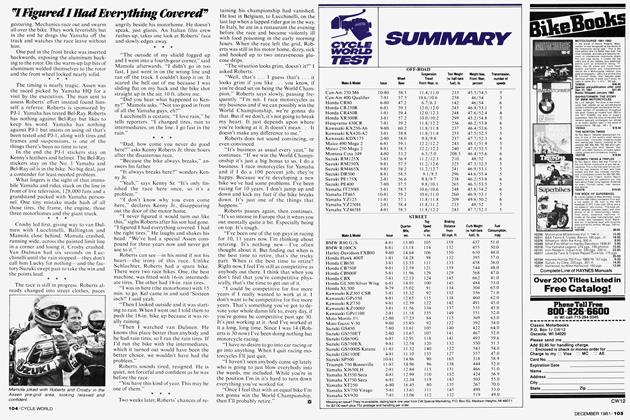

ACCELERATION