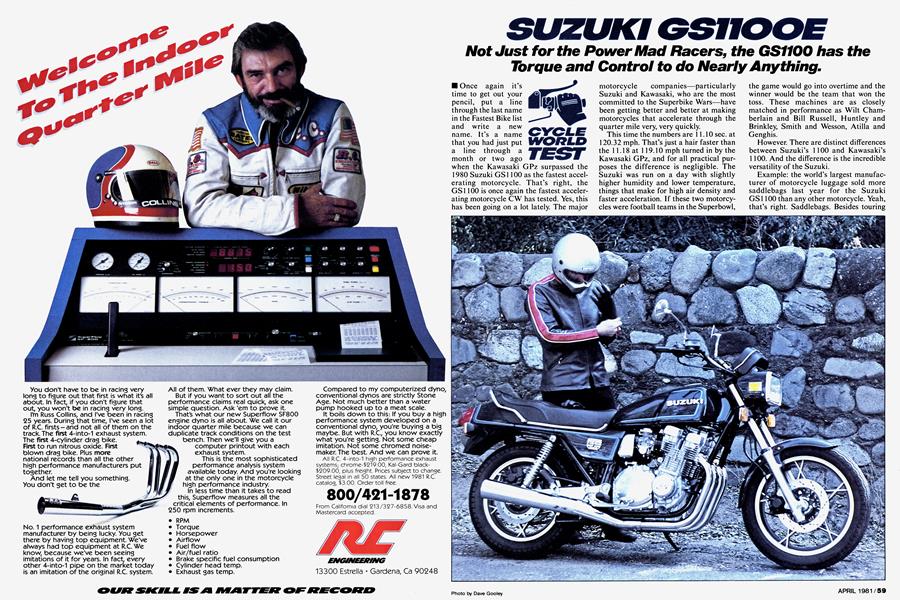

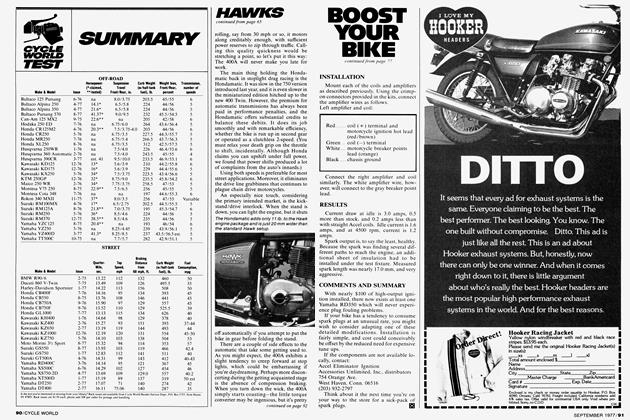

SUZUKI GS1100E

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Not Just for the Power Mad Racers, the GS1100 has the Torque and Control to do Nearly Anything.

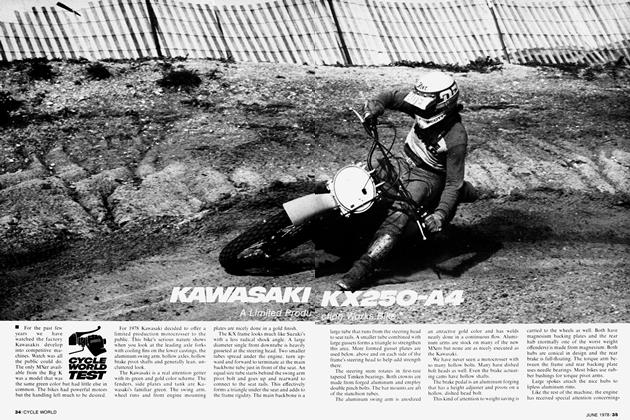

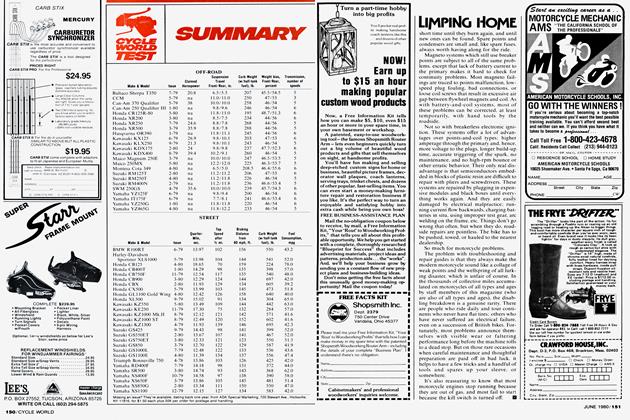

Once again it's time to get out your pencil, put a line through the last name in the Fastest Bike list and write a new name. It's a name that you had just put a line through a month or two ago When the Kawasaki GPz surpassed the 1980 Suzuki GS1100 as the fastest accelrating motorcycle. That's right, the S1 100 is once again the fastest acceler uing motorcycle CW has tested. Yes, this las been going on a lot lately. The major

motorcycle companies—particularly

Suzuki and Kawasaki, who are the most committed to the Superbike Wars—have been getting better and better at making motorcycles that accelerate through the quarter mile very, very quickly.

This time the numbers are 11.10 sec. at 120.32 mph. That’s just a hair faster than the 11.18 at 119.10 mph turned in by the Kawasaki GPz, and for all practical purposes the difference is negligible. The Suzuki was run on a day with slightly higher humidity and lower temperature, things that make for high air density and faster acceleration. If these two motorcycles were football teams in the Superbowl,

the game would go into overtime and the winner would be the team that won the toss. These machines are as closely matched in performance as Wilt Chamberlain and Bill Russell, Huntley and Brinkley, Smith and Wesson, Atilla and Genghis.

However. There are distinct differences between Suzuki’s 1100 and Kawasaki’s 1100. And the difference is the incredible versatility of the Suzuki.

Example: the world’s largest manufacturer of motorcycle luggage sold more saddlebags last year for the Suzuki GS1100 than any other motorcycle. Yeah, that’s right. Saddlebags. Besides touring from staging lights to trap lights, from green flag to checkered flag, the GS1100 is a great motorcycle for touring from, say, Schenectady to San Francisco.

Even that doesn’t cover the range of ability of the Suzuki. It starts easily when cold, idles through traffic, handles fine on bumpy freeways or crooked canyon roads. It can carry two-up or solo. It can do, in fact, anything a street bike should do.

Just as the performance of the GS1100 is so versatile, the parts that make it so are of a uniform excellence. This is not a wonderful machine because of the engine or because of the suspension, but because of all the pieces. The multi-adjustable suspension enables the bike to be either luxuriously plush or stable handling. And the engine offers the same range of abilities, from smooth idling to high torque to peak horsepower.

Four cylinder, inline, air-cooled, dual overhead cam motors have become the standard for motorcycle power plants, and for good reason. They offer excellent power, moderate weight and size, they are smooth and can be made durable and reliable.

Suzuki’s interpretation of this theme is straightforward and thoughtful. Its biggest claim to fame is the TSCC (Twin Swirl Combustion Chamber) head. For the record, there’s nothing novel about getting the intake mixture to swirl around the combustion chamber. Lots of engines are designed to promote swirl, and that in turn helps fill the cylinder evenly with a well-vaporized mixture. The swirl is particularly important at small and medium throttle openings and at slower engine speeds when cylinder vacuum is high. Normally a wedge-type combustion chamber is used to get high amounts of swirl and it’s common on most automotive engines. But the Suzuki system (originally designed by an Italian engineer, Vincezo Piatti) achieves the swirl in a different way. Rather than having the mixture swirl around the cylinder as if it were running around the circumference of the cylinder, the TSCC tilts the axis of the swirl 90 ° so the intake mixture swirls in the same direction as the motorcycle’s tires rotate. And with two intake valves and two exhaust valves, there are two of these swirls occurring in the combustion chamber, hence the name.

Operating the eight intake valves and eight exhaust valves are a pair of overhead camshafts, which is normal contemporary practice, but in between the cams and the valves are lever-type cam followers, not the usual shims and buckets. Besides the benefits of the swirl, the system, as developed by Suzuki, ties together numerous engineering themes, such as the small valves, narrow included angle, reduced height of the head, and better valve cooling.

For the owner who likes to maintain his bike himself the system has one important benefit: valve adjusting doesn’t require a box of expensive shims. The procedure is as simple as that of your father’s (or grandfather’s) ’28 Chevy. A locking nut holds the position of the screw-type adjuster on the end of the cam follower. The only difficulty is the sheer number of 16 valve adjusters.

What the TSCC and all the other wonders in the Suzuki’s engine are supposed to do is make the Suzuki go fast, run well and hold together. At that, the Suzuki is a success. But. Compared with other engines of the same size, it appears there are other ways of getting comparable performance.

Witness the Kawasaki GPzllOO. The mechanical components are all normal: two valves per cylinder and nothing special about the design, at least on the surface. True, it has electronic fuel injection, but the fuel injection only has a noticeable effect at low and moderate engine speeds where the mixture is more precisely metered. For peak power there is no substantial difference in performance between the Kawasaki and Suzuki 1100s. Just two different ways to the same result.

That’s in stock trim, though. Both these machines are in surprisingly mild states of tune, all things considered, and either one can develop the 105 to 110 horsepower it takes to blitz the quarter mile with a 119 or 120 mph trap speed.

Tuned to within an inch of its life, the TSCC 16 valve head likely can produce more horsepower than an equivalent engine with an eight valve head. That’s why the International Drag Bike Association changed the power-to-displacement rules for four-valve-per-cylinder bikes last year after Terry Vance decimated records with his GS1100-based Pro Stocker. The potential is there.

This engine isn’t just for racing. Its enormous torque makes it a natural for the full dress touring crowd. And it’s amazingly smooth for its size, even without a rubber-mounted engine. Now that the federal emission rules have quit changing all the motorcycle manufacturers can settle down to meeting the rules and preserving good throttle response, something that Suzuki is learning about. The 1100 started easily when cold, provided the choke knob on the steering head was pulled out all the way. It would idle at maybe 3000 or 4000 rpm until the knob was pushed in a ways, but could still be ridden immediately from cold, something that we couldn’t say about many Suzukis a couple of years ago.

Even compared with last year’s GS1100 the machine runs better. Apparently the only change is a different air bleed jet in the carbs, but low speed throttle response is substantially improved. No more is there a slight hesitation or jerkiness to the engine at low speeds. Not ridden carefully it’s still possible to bring out typical CV carb suddenness, but it’s much less a constant problem than it was and it makes the 1100 more enjoyable to ride leisurely.

Whether the GS1100 is ridden leisurely or hard, the suspension has a combination of settings that is appropriate. This is surely the most adjustable motorcycle suspension available. The forks, for instance, have four damping adjustments, four spring preload adjustments, plus a person could ignore the factory recommendations and change the air pressure. That doesn’t even include changes in fork oil level or viscosity. Shocks have four damping settings and five preload settings.

This combination of adjustments can give a rider the wrong setting as easily as the right setting, but as long as the rider figures out what combination works best he can get either a superior ride or a firm and stable suspension.

Air pressure changes aren’t recommended on the forks because increased air pressure can reduce effective travel. That’s why the bike comes with 7.1 psi of pressure. And a connecting tube links both fork legs so the pressure is the same in both. That also makes measuring and filling the legs easier. Fork spring preload is changed by pulling off the rubber caps on the forks, removing the handlebar, and turning a screw-operated rotating cam at the top of each fork leg. Use a large screwdriver when the bike is on the centerstand and there’s no problem. Try to do it without the bars removed and the screw head will probably be destroyed.

Spring preload affects the ride height of the front end. Used properly it can compensate for different loads. With a fairing installed preload can be set up a notch or two. And when preload is increased, the damping can be correspondingly stiffened. The range of adjustments is very good. Set at the softest the bike is soft riding and comfortable, yet won’t wallow or wobble when pressed. At mid-range settings the bike becomes much tighter feeling. It doesn’t dive as much when direction is changed and it responds quicker to handlebar movements. At the firmest settings the suspension is still compliant, but very stiff. The rider feels bumps and dips and there’s less movement of the suspension when cornering. Unless the rider weighs as much as a big dirt bike the stiffest settings won’t improve handling because the bike can skitter around too much. But for twoup full-dress touring the stiffest settings keep the mighty Suzuki safe and stable.

Steering precision of the GS1100 must be qualified. Like the World’s Strongest Woman, the big Suzuki is very good, but pays a price for its size. Given that it has a 60.5 in. wheelbase and weighs a little over 550 lb., the Suzuki handles very well. Large, heavy motorcycles however, don’t respond to steering input as well as smaller, lighter motorcycles. And the Suzuki, to once again make comparisons with the GPzllOO Kawasaki, is a little more vague in responding to rider commands.

While the weight and size may be a challenge for the suspension and frame and tires, the brakes handle the load admirably. As with the other big Suzukis, the GS1100 has the best brakes in its class. They are responsive, take just the right pressure, are controllable and resist fade. The angled lines drilled through the triple discs are probably, as Suzuki says, just for looks, but they certainly don’t interfere with the exceptional performance of the brakes. And the rest of the components, the calipers and pads and master cylinder, are an ideal combination of pieces. If it weren’t for the brakes on this bike, the brakes on lots of other bikes would seem much better than they are.

Shifting the transmission is as satisfying as using the brakes. Lever pressure is light, shifts are positive and it rarely misses a shift. And the clutch, which may not be quite as strong as that of the other fast 1100, was easily able to handle the drag strip chores. Plus it required relatively light lever pressure and engaged smoothly and positively.

Polished is perhaps the best word to describe the way the Suzuki works. Everything on it works smoothly and easily. The few minor annoyances on last year’s GS1100 are either eliminated, or have become less annoying now that we’ve become accustomed to them. There’s now a normal fuel petcock on the bike, vacuum operated, with reserve and prime settings, so the rider doesn’t rely entirely on a gauge that’s not perfectly accurate.

Instrument lighting is now very good. The light seems to come through the instrument face, marking the redline of the tach in bright red at night, while the needles and odometer are easily readable. First time someone rode the GS1100 the signal light switch felt odd, with its five notches. Now that everyone is used to it, it works fine and makes sense. Just push it full left or full right, and if you want to cancel it yourself, just push it back to• wards center. The self canceller doesñ'i eliminate manual return as do some othei systems.

Perhaps the styling, which hasn'i changed at all, has grown on us the most, First photos of the original GS1 100 were from the European shows where the bike came with a huge hunch-backed bas tank that made everything on the bike look wrong. Then came the stock U.S. mode] 1100 and many riders couldn't get used tc the huge rectangular headlight, the noselike tailpiece, the lunchbox-like instru ment pod. Now a year later everything i5 beginning to fit. The tailpiece is blending in with the rest of the body panels. The appearance of bulk and weight is disap pearing. People around this office whc used to make rude comments about the GS1 100's looks now use it as an example of elegant design.

One thing that hasn't changed aboul the GS 1100, or how we think of it, is per formance. It's still magnificent. There'~ still a thrill in blasting away from peoph on mere 1000cc bikes as if you weren'l even trying. It's still fun to disappear frorr passed cars without even shifting down That sitting in-the-oval-office-with-the red-button feeling never fades. It's th same feeling Ronald and Leonoid mus share, that Nikita and Ike shared. And it'~ a feeling that the GS1 100 rider and th GPz1 100 rider share. It's a feeling of con trol over not just the tire-smoking power 01 the motorcycle, but over poor souls or 750s and l000s who don't gun their en gines and power away like they do wher you ride the XL500 to work.

But the Suzuki, unlike that othei low-i 1-sec. bike, has a much wider appeal It isn't just the Chrondek-for-lunch-bunci that crave the GS1 100's power, it's als touring riders who find the adjustable sus pension, the comfortable seat, the smooti reliability of the engine and the ampli load capacity of the Suzuki just what the3 want.

No one will ever accuse the GSI 100 01 being a Rodney Dangerfield of motorcy des. Above all else, it gets respect.

SUZUKI GS1100E

$3999