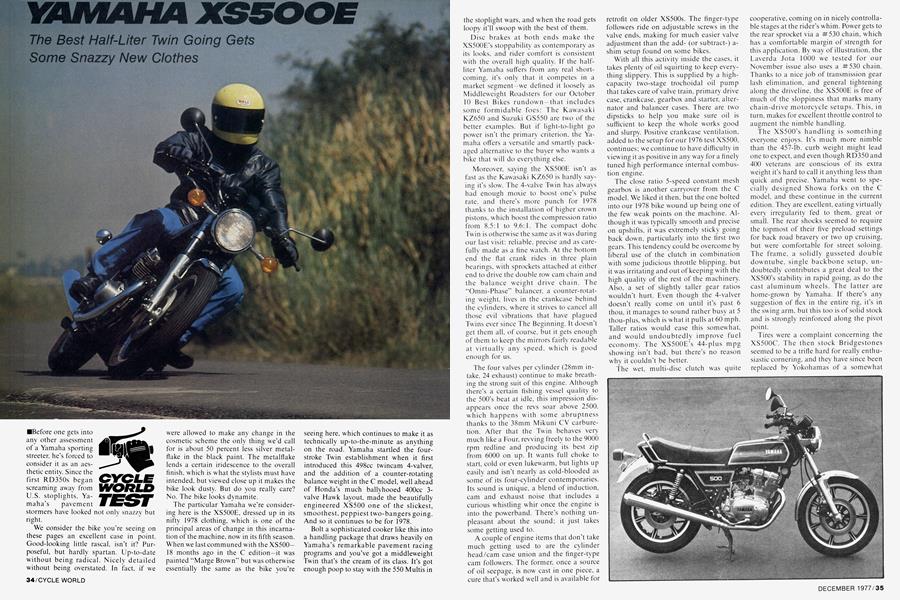

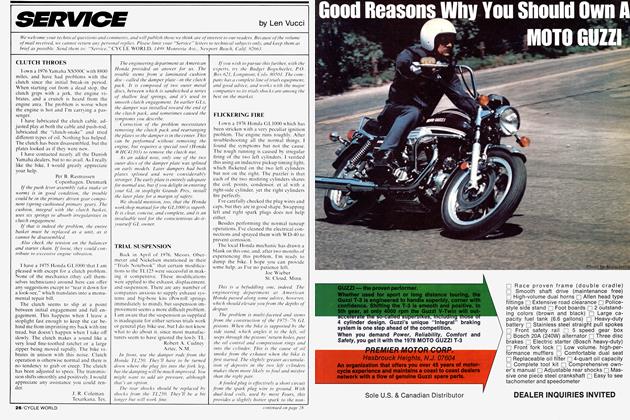

YAMAHA XS500E

CYCLE WORLD TEST

The Best Half-Liter Twin Going Gets Some Snazzy New Clothes

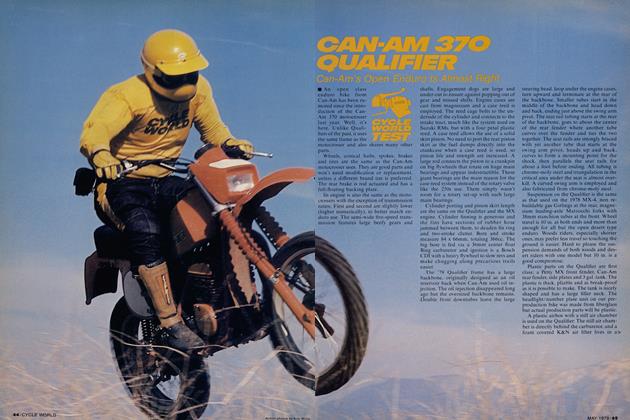

Before one gets into any other assessment of a Yamaha sporting Streeter, he’s forced to consider it as an aesthetic entity. Since the first RD350s began screaming away from U.S. stoplights. Yamaha’s pavement stormers have looked not only snazzy bul right.

We consider the bike you're seeing on these pages an excellent case in point. Good-looking little rascal, isn't it? Pur poseful, but hardly spartan. Up-to-date without being radical. Nicely detailed without being overstated. In fact, if we

were allowed to make any change in the cosmetic scheme the only thing we’d call for is about 50 percent less silver metalflake in the black paint. The metalflake lends a certain iridescence to the overall finish, which is what the stylists must have intended, but viewed close up it makes the bike look dusty. But do you really care? No. The bike looks dynamite.

The particular Yamaha we’re considering here is the XS500E, dressed up in its nifty 1978 clothing, which is one of the principal areas of change in this incarnation of the machine, now in its fifth season. When we last communed with the XS500— 18 months ago in the C edition—it was painted “Marge Brown” but was otherwise essentially the same as the bike you’re

seeing here, which continues to make it as technically up-to-the-minute as anything on the road. Yamaha startled the fourstroke Twin establishment when it first introduced this 498cc twincam 4-valver, and the addition of a counter-rotating balance weight in the C model, well ahead of Honda's much ballyhooed 400cc 3valve Hawk layout, made the beautifully engineered XS500 one of the slickest, smoothest, peppiest two-bangers going. And so it continues to be for 1978.

Bolt a sophisticated cooker like this into a handling package that draws heavily on Yamaha's remarkable pavement racing programs and you've got a middleweight Twin that's the cream of its class. It's got enough poop to stay with the 550 Multis in the stoplight wars, and when the road gets loopy it’ll swoop with the best of them.

Disc brakes at both ends make the XS500E’s stoppability as contemporary as its looks, and rider comfort is consistent with the overall high quality. If the halfliter Yamaha suffers from any real shortcoming, it’s only that it competes in a market segment—we defined it loosely as Middleweight Roadsters for our October 10 Best Bikes rundown —that includes some formidable foes: The Kawasaki KZ650 and Suzuki GS550 are two of the better examples. But if light-to-light go power isn’t the primary criterion, the Yamaha offers a versatile and smartly packaged alternative to the buyer who wants a bike that will do everything else.

Moreover, saying the XS500E isn’t as fast as the Kawasaki KZ650 is hardly saying it’s slow. The 4-valve Twin has always had enough moxie to boost one’s pulse rate, and there’s more punch for 1978 thanks to the installation of higher crown pistons, which boost the compression ratio from 8.5:1 to 9.6:1. The compact dohc Twin is otherwise the same as it w^as during our last visit: reliable, precise and as carefully made as a fine watch. At the bottom end the fiat crank rides in three plain bearings, with sprockets attached at either end to drive the double row' cam chain and the balance weight drive chain. The “Omni-Phase” balancer, a counter-rotating weight, lives in the crankcase behind the cylinders, where it strives to cancel all those evil vibrations that have plagued Twins ever since The Beginning. It doesn't get them all. of course, but it gets enough of them to keep the mirrors fairly readable at virtually any speed, which is good enough for us.

The four valves per cylinder (28mm intake, 24 exhaust) continue to make breathing the strong suit of this engine. Although there's a certain fishing vessel quality to the 500’s beat at idle, this impression disappears once the revs soar above 2500. which happens with some abruptness thanks to the 38mm Mikuni CV carbure -tion. After that the Twin behaves very much like a Four, revving freely to the 9000 rpm redline and producing its best zip from 6000 on up. It wants full choke to start, cold or even lukewarm, but lights up easily and isn't nearly as cold-blooded as some of its four-cylinder contemporaries. Its sound is unique, a blend of induction, cam and exhaust noise that includes a curious whistling whir once the engine is into the powerband. There’s nothing unpleasant about the sound; it just takes some getting used to.

A couple of engine items that don't take much getting used to are the cylinder head/cam case union and the finger-type cam followers. The former, once a source of oil seepage, is now cast in one piece, a cure that’s worked well and is available for retrofit on older XS500s. The finger-type followers ride on adjustable screws in the valve ends, making for much easier valve adjustment than the add(or subtract-) ashim setup found on some bikes.

With all this activity inside the cases, it takes plenty of oil squirting to keep everything slippery. This is supplied by a highcapacity two-stage trochoidal oil pump that takes care of valve train, primary drive case, crankcase, gearbox and starter, alternator and balancer cases. There are two dipsticks to help you make sure oil is sufficient to keep the whole works good and slurpy. Positive crankcase ventilation, added to the setup for our 1976 test XS500, continues; we continue to have difficulty in viewing it as positive in any way for a finely tuned high performance internal combustion engine.

The close ratio 5-speed constant mesh gearbox is another carryover from the C model. We liked it then, but the one bolted into our 1978 bike wound up being one of the few weak points on the machine. Although it was typically smooth and precise on upshifts, it was extremely sticky going back down, particularly into the first two gears. This tendency could be overcome by liberal use of the clutch in combination with some judicious throttle blipping, but it was irritating and out of keeping with the high quality of the rest of the machinery. Also, a set of slightly taller gear ratios wouldn't hurt. Even though the 4-valver doesn’t really come on until it’s past 6 thou, it manages to sound rather busy at 5 thou-plus, which is what it pulls at 60 mph. Taller ratios would ease this somewhat, and would undoubtedly improve fuel economy. The XS500E’s 44-plus mpg showing isn't bad, but there’s no reason why it couldn’t be better.

The wet, multi-disc clutch was quite cooperative, coming on in nicely controllable stages at the rider’s whim. Power gets to the rear sprocket via a #530 chain, which has a comfortable margin of strength for this application. By way of illustration, the Laverda Jota 1000 we tested for our November issue also uses a #530 chain. Thanks to a nice job of transmission gear lash elimination, and general tightening along the driveline, the XS500E is free of much of the sloppiness that marks many chain-drive motorcycle setups. This, in turn, makes for excellent throttle control to augment the nimble handling.

The XS500’s handling is something everyone enjoys. It’s much more nimble than the 457-lb. curb weight might lead one to expect, and even though RD350 and 400 veterans are conscious of its extra weight it’s hard to call it anything less than quick and precise. Yamaha went to specially designed Showa forks on the C model, and these continue in the current edition. They are excellent, eating virtually every irregularity fed to them, great or small. The rear shocks seemed to require the topmost of their five preload settings for back road bravery or two up cruising, but were comfortable for street soloing. The frame, a solidly gusseted double downtube, single backbone setup, undoubtedly contributes a great deal to the XS500’s stability in rapid going, as do the cast aluminum wheels. The latter are home-grown by Yamaha. If there’s any suggestion of flex in the entire rig, it’s in the swing arm. but this too is of solid stock and is strongly reinforced along the pivot point.

Tires were a complaint concerning the XS500C. The then stock Bridgestones seemed to be a trifle hard for really enthusiastic cornering, and they have since been replaced by Yokohamas of a somewhat

YAMAHA

XS500E

$1589

Tests performed at Number One Products

Tests performed at Number One Products

softer compound. These provide plenty of stick, although it’s still a touchy business to drag anything on the ground when you’re smokin’ thanks to the excellent cornering clearance on both sides.

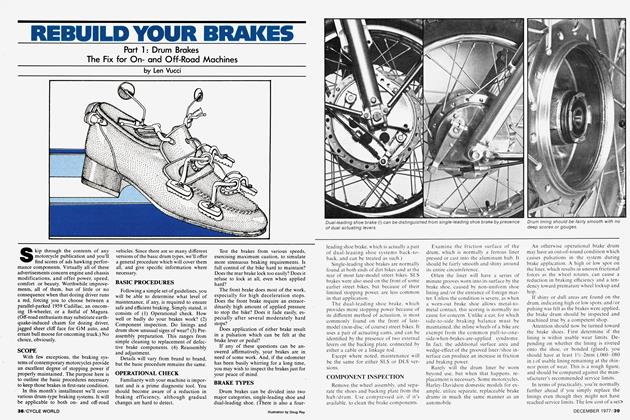

We’re not sure whether the new' tires have augmented the new' XS500’s stopping. which wasn't quite as good on our E model test bike as it was on the C. The C hauled down from 60 mph in an outstanding 127 feet. The E required somewhat more space, and showed a lot of forward weight transfer with consequent rear wheel hop. Nevertheless, the two-disc setupinstalled by Yamaha because it w'as more economical to mate to the aluminum wheels—is very good indeed. The forward

caliper is mounted behind the fork leg, for reduced steering inertia, and there are provisions on the left-hand fork leg for an extra caliper and disc, which could be a very useful addition for anyone planning to go the cafe route with this bike.

Electrics are reasonably simple and nicely packaged, with the fuse box and battery stowed beneath the seat and the wiring running up the backbone to the instruments and controls. One of the latter is a headlight switch. You can’t actually ride your Yamaha with the headlamp oft. but you can start it sans lights if you like. The headlamp cuts in once the engine starts. We prefer having complete sovereignty over our own headlamps, of

course, but this arrangement at least allows the rider an opportunity to get the most from his battery without competition from the bike’s lighting.

Instrumentation is standard, which is to say good, and the tach and speedometer faces are illuminated by a soft green light that’s easy to live with in extended night riding. The by-now'-familiar self-canceling turn signals, a touch we’d like to see on other bikes, are also part of the package.

The riding position on the XS500 continues to be rather upright, w'hich is fine for street use but not quite so welcome when you’re out barnstorming. This is partly a function of the handlebars— topped off with ribbed rubber grips that can become a trifle firm in extended use, besides their marked tendency to smudge the rider’s hands—and partly a function of the seat. The latter is perfectly comfortable, but slopes upward toward the rear of the bike making it somewhat difficult to sit well back. The seat frame also shows a substantial amount of flex, although this didn't seem to present any problems for any of the test riders. A nice touch is the so-called passenger safety strap, which is fastened under the seat with twx) bolts. Remove these and the strap is gone completely—no holes, no trace of its presence.

Other than the cavity that embraces the battery and fuse box, plus the little tray for the bike’s unusually comprehensive tool kit (at seat’s extreme rear), there’s no subseat storage space.

Cosmetically, the Yamaha XS500E mixes elements of “Star Wars” and “Hard Times.” From tank to the rear of the seat, the look, augmented by the black paint and snazzy gold striping, says tomorrow. But the headlamp and taillamp say yesterday. Yamaha had the taillamp neatly butted into the fiberglass bobtail on the C model, then cluttered the look with an afterthought license plate lamp and mounting bracket. On the E. the designers have reverted to the same style taillamp as employed on the more classically styled XS65Ö. It looks OK on the latter, but out of place on this machine. Another backward step, although not so out of harmony w'ith the bike’s overall looks, is the return to chrome fenders. The C model sported slick-looking plastic fenders that apparently did not increase the bike’s performance on the showroom floor.

However, we fully expect to see XS500Es running around out there wearing threeeighths fairings, skinny little seats and other cafe paraphernalia. It won’t take much to push the 500’s already jazzy looks in this direction.

Yamaha rather modestly calls this nifty little bundle “an example of w'hat a fourstroke Twin should be.” We could perhaps edit that to read “The example of what a four-stroke Twdn should be.” §l