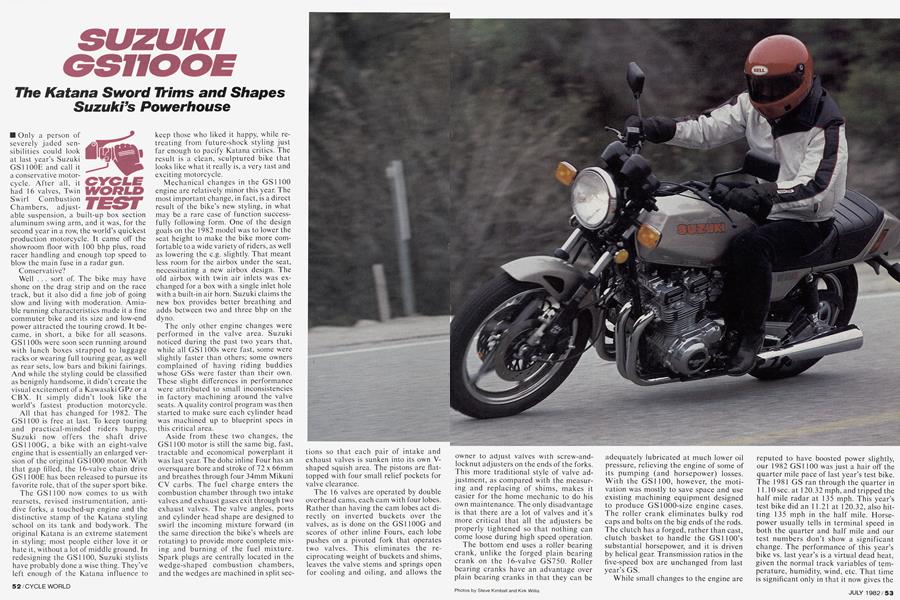

SUZUKI GS1100E

CYCLE WORLD TEST

The Katana Sword Trims and Shapes Suzuki's Powerhouse

Only a person of severely jaded sensibilities could look at last year’s Suzuki GS1100E and call it a conservative motorcycle. After all, it had 16 valves, Twin Swirl Combustion Chambers, adjustable suspension, a built-up box section aluminum swing arm, and it was, for the second year in a row, the world’s quickest production motorcycle. It came off the showroom floor with 100 bhp plus, road racer handling and enough top speed to blow the main fuse in a radar gun.

Conservative?

Well . . . sort of. The bike may have shone on the drag strip and on the race track, but it also did a fine job of going slow and living with moderation. Amiable running characteristics made it a fine commuter bike and its size and low-end power attracted the touring crowd. It became, in short, a bike for all seasons. GS1100s were soon seen running around with lunch boxes strapped to luggage racks or wearing full touring gear, as well as rear sets, low bars and bikini fairings. And while the styling could be classified as benignly handsome, it didn’t create the visual excitement of a Kawasaki GPz or a CBX. It simply didn’t look like the world’s fastest production motorcycle.

All that has changed for 1982. The GS1100 is free at last. To keep touring and practical-minded riders happy, Suzuki now offers the shaft drive GS1100G, a bike with an eight-valve engine that is essentially an enlarged version of the original GS1000 motor. With that gap filled, the 16-valve chain drive GSI 100E has been released to pursue its favorite role, that of the super sport bike.

The GS1100 now comes to us with rearsets, revised instrumentation, antidive forks, a touched-up engine and the distinctive stamp of the Katana styling school on its tank and bodywork. The original Katana is an extreme statement in styling; most people either love it or hate it, without a lot of middle ground. In redesigning the GS1100, Suzuki stylists have probably done a wise thing. They’ve left enough of the Katana influence to keep those who liked it happy, while retreating from future-shock styling just far enough to pacify Katana critics. The result is a clean, sculptured bike that looks like what it really is, a very tast and exciting motorcycle.

Mechanical changes in the GS1100 engine are relatively minor this year. The most important change, in fact, is a direct result of the bike’s new styling, in what may be a rare case of function successfully following form. One of the design goals on the 1982 model was to lower the seat height to make the bike more comfortable to a wide variety of riders, as well as lowering the c.g. slightly. That meant less room for the airbox under the seat, necessitating a new airbox design. The old airbox with twin air inlets was exchanged for a box with a single inlet hole with a built-in air horn. Suzuki claims the new box provides better breathing and adds between two and three bhp on the dyno.

The only other engine changes were performed in the valve area. Suzuki noticed during the past two years that, while all GS1100s were fast, some were slightly faster than others; some owners complained of having riding buddies whose GSs were faster than their own. These slight differences in performance were attributed to small inconsistencies in factory machining around the valve seats. A quality control program was then started to make sure each cylinder head was machined up to blueprint specs in this critical area.

Aside from these two changes, the GS1100 motor is still the same big, fast, tractable and economical powerplant it was last year. The dohc inline Four has an oversquare bore and stroke of 72 x 66mm and breathes through four 34mm Mikuni CV carbs. The fuel charge enters the combustion chamber through two intake valves and exhaust gases exit through two exhaust valves. The valve angles, ports and cylinder head shape are designed to swirl the incoming mixture forward (in the same direction the bike’s wheels are rotating) to provide more complete mixing and burning of the fuel mixture. Spark plugs are centrally located in the wedge-shaped combustion chambers, and the wedges are machined in split sections so that each pair of intake and exhaust valves is sunken into its own Vshaped squish area. The pistons are flattopped with four small relief pockets for valve clearance.

The 16 valves are operated by double overhead cams, each cam with four lobes. Rather than having the cam lobes act directly on inverted buckets over the valves, as is done on the GSI 100G and scores of other inline Fours, each lobe pushes on a pivoted fork that operates two valves. This eliminates the reciprocating weight of buckets and shims, leaves the valve stems and springs open for cooling and oiling, and allows the owner to adjust valves with screw-andlocknut adjusters on the ends of the forks. This more traditional style of valve adjustment, as compared with the measuring and replacing of shims, makes it easier for the home mechanic to do his own maintenance. The only disadvantage is that there are a lot of valves and it’s more critical that all the adjusters be properly tightened so that nothing can come loose during high speed operation.

The bottom end uses a roller bearing crank, unlike the forged plain bearing crank on the 16-valve GS750. Roller bearing cranks have an advantage over plain bearing cranks in that they can be adequately lubricated at much lower oil pressure, relieving the engine of some of its pumping (and horsepower) losses. With the GS1100, however, the motivation was mostly to save space and use existing machining equipment designed to produce GS 1000-size engine cases. The roller crank eliminates bulky rod caps and bolts on the big ends of the rods. The clutch has a forged, rather than cast, clutch basket to handle the GS1 100’s substantial horsepower, and it is driven by helical gear. Transmission ratios in the five-speed box are unchanged from last year’s GS.

While small changes to the engine are

reputed to have boosted power slightly, our 1982 GS 1100 was just a hair off the quarter mile pace of last year’s test bike. The 1981 GS ran through the quarter in 11.10 sec. at 120.32 mph, and tripped the half mile radar at 135 mph. This year’s test bike did an 11.21 at 120.32, also hitting 135 mph in the half mile. Horsepower usually tells in terminal speed in both the quarter and half mile and our test numbers don’t show a significant change. The performance of this year’s bike vs. last year’s is a virtual dead heat, given the normal track variables of temperature, humidity, wind, etc. That time is significant only in that it now gives the Kawasaki GPzl 100 a knife-edge lead in the big bike performance battle. The 1982 Kawasaki (May, 1982) turned an 11.18 sec. at 120.16 mph quarter, with a half mile speed, also, of 135 mph. That’s a little slower than last year’s GS and a little quicker than this year’s.

What all this tells us is that both bikes are tremendously fast and powerful, and either, on a good day with the right prevailing winds, will edge out the other by an almost meaningless margin.

The Japanese are now squeezing astounding quarter mile performance out of smaller engines, with 550s accelerating into the mid-12s. Much work has been done the past few years, and is still being done, to broaden the powerbands of these engines so that they pull well out of corners and accelerate hard without having the tach needle pegged. Progress has been made, but when it comes to ready, arm yanking power at any rpm, nothing beats cubic inches.

The GS1100 engine is a highly tuned powerplant, rated at 108 bhp at 8500 rpm, with peak torque of 67.6 lb.-ft. at 6500 rpm. You would expect the bike to get well out of its own way at the high end of the tach, but the pleasant surprise in stepping back on a GS1100 after a short absence is in how well it pulls from the growling bottom of its rev band. From idle up to 4000 rpm the bike pulls like a truck—a very fast truck—and the rider, if he wanted to, could get into all kinds of legal trouble without ever breaking into the top half of the tach.

The GS1100 finally comes with the choke lever mounted at the left handlebar rather than in the center of the steering stem. Remote choke lever locations are not a big problem on all bikes, but Suzukis as a group need a lot of choke fiddling during the first minute or two after startup. The engine starts immediately on full choke and then goes to about 4500-rpm-and-climbing unless the choke is quickly backed off about half way. The bike can be ridden away on half choke and reduced to full off after about a minute of riding, in moderate temperature conditions.

Throttle response is good but there is a small amount of lean surge at steadystate cruising speeds and low throttle openings. It feels as though the carb pistons are undecided as to where, exactly, they want to position themselves. At higher road speeds, during hard riding, or in the fast-slow transitions of daily riding no carb problem is evident and the throttle is quick and responsive.

Climbing on the GS1100 for a ride, it becomes apparent that more than just the bike’s styling has been changed. The tank is longer than last year’s and the leading edge of the seat is 4 in. farther back than before. The footpegs are rearset a corresponding amount, and the redesigned seat has been lowered an inch. This combination gives the rider an impression of being more tucked into the bike, rather than perching on top of it as before. The handlebars are long, by sport bike standards, and reach a long way back to meet you. Fortunately, the Suzuki still uses easily replaced tubular bars rather than forged aluminum pieces, so the rider can cheaply and easily install any handlebars that make him happy. In any case, the rider looks out over a long tank and sits relatively rearward on the bike.

The frame of the GS1100 is virtually unchanged but the bike has all new front forks with anti-dive, adjustable spring preload, four-way adjustable damping and air assist. Spring preload is set by turning a slotted screw under the fork caps to one of four positions. The screw operates a notched adjusting collar in the top of the fork leg, compressing the fork spring like a smaller version of the typical preload ramp on a rear shock absorber.

Last year’s GS used a leading axle fork with the adjustable damping rods going straight up through the centers of the fork legs, with adjustment wheels at the bottom. Addition of anti-dive valves this year has moved the axle back to the center of the fork legs, so damping adjusters are now at the bottoms of cast-in oil galleries on the sides of the fork legs. Knurled black plastic knobs, numbered for four damping positions, are located just above the axle. Turning the knob raises or lowers rebound damping by rotating smaller or larger oil restriction holes in line with the oil gallery.

The anti-dive units bolted to the fronts of the fork legs use hydraulic pressure from the front brakes to control fork movement. Pressure in the brake lines acts on spring loaded valves in the antidive unit, restricting oil flow through the fork rods. The more brake pressure, the greater the restriction. Full application of the brakes (more than 29 lb. of lever pull) seats the anti-dive valve so no oil gets through. The unit also contains a blow-off valve, so if a sharp road shock hits the suspension under braking the forks can still absorb the blow rather than transmitting the shock into the chassis.

Use of a center axle fork and changes at the triple clamps have moved the rake/trail figures around on the GS. It now has 28° of rake and 4.57 in. of trail, vs. 27° and 4.06 in. last year. Wheelbase has been reduced from 59.8 in. to 59.4 in. The idea behind these changes was to make the bike a bit more stable at the very high speeds of which it’s capable (more rake and trail) and at the same time to quicken steering reaction when the bike is turned into a corner (shorter wheelbase).

Both achieved the intended effect; a couple of days on mountain roads and a full day of track testing failed to uncover any defects in the bike’s handling. The GS1100 is a big long bike and it feels like one; no rider will ever be deceived into thinking he’s on a 550, but it carries its weight and size very well. Steering input to set the bike up for a corner is light and precise, and high speed handling is dead stable in sweeping corners or in a straight line. Our test rider went out of his way to initiate speed wobbles by shutting the throttle off and turning it back on in Willow’s fast Turn Eight. The big Suzuki merely shuddered slightly and continued through the corner under control. If the back tire is hung out slightly in a corner, the GS recovers well, without wobbling or trying to high-side. The bike is forgiving.

At absolute race track speeds, the only limit is ground clearance, which is not 'quite as good as the Kawasaki GPzl 100’s. The centerstand and sidestand drag first. Removing those gives a good increase in cornering clearance, and the footpegs and muffler heat shields drag next. If the bike is pushed hard with the pegs dragging, the stock tires begin to heat up and lose traction.

That is under continuous race.track use.

On the street it’s possible to ride very hard with no more than the occasional scrape of the centerstand. The tires work superbly. The anti-dive forks help maintain good ground clearance under heavy braking into corners, and the fully adjustable suspension allows the rider to set up the ride for loading and road conditions.

Stock suspension settings, as delivered, are 7.1 psi air pressure in the forks with the springs on full soft and damping set to #2. The shocks are set with preload and damping both on full soft. The owner’s manual advises leaving the air pressure at 7.1 psi under all conditions and adjusting spring preload and/or damping to cope with different loads or riding preferences. The stock settings work very well for solo riding, and the suspension can be dialed up, if the rider prefers a stiffer ride, without hurting the handling.

On the race track, the best compromise between suspension compliance and optimum ground clearance worked out to be 12 psi in the forks, fork damping on Four and spring preload on One, with the rear shocks on Four for both damping and preload. The extra air pressure helped cornering clearance while providing more progressive springing and better compliance over bumpy turns than high spring preload allowed.

As with all machines offering a lot of adjustment, it is possible to get the Suzuki’s suspension fouled up. But as long as recommended settings—and sensible adjustments to those settings—are used, the Suzuki provides exemplary big bike handling on the track and on the street.

In a footnote to suspension setup, the GS may have a Japanese First; a set of stock shocks that don’t go away with hard use. They continued to work perfectly during extended track testing, and we even have an early-season report from an endurance racer who says he hasn’t bothered to change them yet because they are still working fine.

The Suzuki’s brakes are also excellent: hard stopping, predictable and easily modulated without gorilla-like lever pressure, and they felt as good on the race track as they did in city traffic. Besides feeling good, they produced good numbers during our braking test, stopping from 30 mph in 32 ft. and from 60 mph in 129 ft., both distances slightly better than average for a bike of the GS1100’s weight.

Weight, by the way, is another area of improvement for this year’s GS. Our bike weighed in at 549 lb. with half a tank of gas, 8 lb. lighter than the old GS, even> though the new one is carrying 3 lb. more fule with the tank half full. Most of this trimming has been accomplished through small savings of a few ounces here and there in dozens of places on the bike, i.e. plastic seat pan, aluminum brake reservoir, smaller and lighter ignition coils.

As part of the GS1 100’s facelift this year, the instruments have been redesigned. The box-like instrument module of last year has been replaced with an instrument cluster, which looks more businesslike and motorcyclish. Gone is the motorcycle picture with Christmas tree warning lights all over it. In its place we have a simple row of warning lights and more prominently, a round oil temperature gauge and a matching fuel gauge on the other side of the panel. The new shapes make the instruments appear as though they came from an airplane, rather than the dash of an economy car.

The fuel gauge on our test bike took forever to crawl down to half a tank, then practically dropped to empty, so its accuracy left some room for improvement. The Suzuki now has a nice big 5.7 gal. tank, an improvement of a full gallon over last year’s 4.7 gal. tank. The top section of the tank is almost flat, so it's one of those tanks that appear full, after surging gas all over the top, then allow you to sneak in about another half gallon. The removable filler cap that has to be set down somewhere, usually on the seat, is not our favorite type, but the gas filler is so nicely integrated into the shape of the tank, it’s hard to complain. The GS averaged 47 mpg on our test loop and never dropped below 35 mpg when pushed hard, so weekend and touring riders will be able to enjoy around 200 to 250 mi. between gas stops. Reserve is a generous 1.2 gal., so there’s no need for immediate suspense when the tank is switched over.

Our test bike, incidentally, ran out of gas and when switched over to reserve was found to be empty. Hmmm. We took the petcock out and found that the plastic piece that forms the upper and lower stand pipes had been installed backwards. We turned it around and it worked fine. Fortunately, we discovered this in our parking lot and not somewhere west of Laramie.

The seat has a small caterpillar-climbing-the-tank section in the front. There is a very slight rise between the front and rear portions of the seat, with more than enough room for both rider and passenger to move around. Padding is good, so the big gas tank can be run dry nonstop. The seat is removable rather than hinged. The ignition key unlocks the seat at the tailpiece and then two wide levers have to be pushed forward to release it. This is sometimes a three-handed operation in which the rear clasp relocks while you wrestle with the side levers. Not too much fun.

The Suzuki’s tailpiece has a small compartment for documents and the usual minimum quality tool kit. The shaped sidecovers snap away from rubber grommets to uncover the battery on one side and fuse block and electrics on the other.

Controls and handlebar switches are well laid out and easy to use. The turn signals are self-cancelling, with a timen that switches them off after 10 sec. of operation if the bike is traveling faster than 9 mph. At lower speeds they don’t cancel so you don’t have to keep switching the signal back on at long stoplights. The 55/60 watt quartz halogen headlight puts out a strong beam with good peripheral lighting on dark roads. Best of all, the big 8-in. bulb is round(!) so (a) it looks like it belongs on a motorcycle and (b) will mate up with a variety of aftermarket fairings without (b sub-1 ) looking ridiculous and (b sub-2) leaking wind all over your frozen body.

That bare, round headlight may be the key to the GS1 100’s personality. Suzuki has told us that the restyling and refinement of the GS is intended to make the bike more appealing to sport riders, now that the shaft drive 1100 is available for touring riders. That suggests a narrowing of the bike’s function, a homing in on a particular segment of the buying public,. In that respect the updated design is successful; the GS1100 now looks like the kind of bike it really is.

On the other hand, the new styling and mechanical improvements do nothing to compromise the bike or take away the broad appeal it has enjoyed in the past. The GS1 100 may be pure powerhouse" sport bike, but it has no small fairingcum-instrument-module to prevent the installation of a full-dress touring fairing (or a Randy Mamola look-alike GP fairing) if the owner wants one. The bodywork is modern, but not so heavily styled that it precludes the use of saddlebags," luggage racks and other accessories. The handlebars are still bars and not castings, so the location of handgrips is easily and cheaply changed to fit the rider. In short, the GS1 100 will work for just about anyone who wants to ride a motorcycle on pavement.

Beyond having its traditional versatility left intact, the GS is simply a good bike made better.

SUZUKI GS1100E

$3999