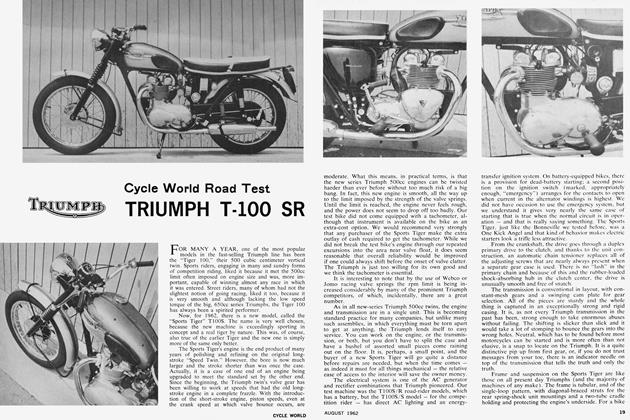

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

KAWASAKI 350 S2

“Gee, It’s Nice To Have A Little Brother."

THE MACH III is a heavy act to follow, having established its reputation as a giant-killer. So readers will undoubtedly be disappointed that the Kawasaki’s new three-cylinder marvel, the 350 S2, is only one of the fastest 350s we’ve tested rather than the fastest.

Perhaps we shouldn’t be so performance-conscious. But the factory rates the output of this new engine at 45 blip, which should put it in a class with the peppiest 500s. The 350 Three is peppy, but not 45 ponies worth. So while Kawasaki searches for the missing horsepower, we will concern ourselves with the virtues of the S2 as it stands. And there are plenty.

Quite obviously, the bike is intended for the performanceminded short haul rider, rather than the long distance touring man. While the S2 sustains highway speeds easily, it is a gasoline gourmand rather than a moderate gourmet. To characterize it further, it is much lighter feeling than the Mach III 500, steers more easily, feels comfortably narrow, has better ground clearance in corners than does the Mach III, and will pop those same delightful (or scary) wheelies in the lower gears.

Mechanically, the S2 has benefited from Kawasaki’s experience with the Mach III. It further sports its own unique styling gimmick, a feisty high-riding tail molding, as well as a bright, flashy paint job.

The S2’s engine is little more than a scaled down version of the powerful 500-cc HI unit. Located within the leak-free, horizontally split, aluminum die-castings of the crankcase is a pressed-together crankshaft with the crank throws set 120 degrees apart. Six ball bearings support the rather long crank assembly, and rubber seals prevent leakage of air into the separate crankcase chambers. The short connecting rods are supported by roller bearings at the big ends of the crankshaft, and the pistons are supported in caged needle bearings. A slight offset of the connecting rods towards the rear (inlet) side of the engine helps minimize piston slap by changing the point of highest lateral combustion pressure, which occurs at top dead center.

Oil for lubrication is supplied by a plunger-type pump controlled by the engine’s rpm and a cable connected to the throttle. Thus, at low engine speeds and throttle openings, less oil is supplied, reducing exhaust smoking and spark plug fouling. Oil from the pump is directed to the left-hand main bearing through a plastic pipe, and is further fed to the right-hand bearing before being mixed with the fuel/air charge to be burned and discharged through the exhaust pipes. Oil is also injected into each intake stub to lubricate the pistons, wrist pins and cylinder walls.

The small 53-mm cylinder bores permit large port areas in relation to the size of the pistons, which leads to a theoretically more efficient engine. The three two-ring pistons ride in cast iron cylinder sleeves, which are fitted into the aluminum alloy cylinder jackets by a cast-in-bond process to assure maximum heat dissipation. When the H1 first appeared, some critics were concerned about possible overheating of the center cylinder due to the blockage of a cooling airflow by the front forks and wheel. But Kawasaki spent much time in the wind tunnel developing a front fender design which permitted sufficient airflow for adequate cooling.

Missing on the S2 are the cast-in “bridges” between the cylinder fins which are employed on the HI, presumably to reduce mechanical noise. Perhaps the engine’s smaller size makes these bridges unnecessary, for mechanical noise is moderate on the S2, and certainly no more than that emanating from the Mach 111.

The three 24-mm Mikuni carburetors supplying the fuel are connected to the aircleaner by short neoprene hoses. When the clutch is withdrawn, the engine is extremely quiet at idle rpm, and the exhaust note remains very low even in full throttle acceleration.

The tly in the ointment is the intake roar produced by the air cleaner when the throttles are opened wide. It’s not an unpleasant sound, but it is one which could become tiring on long high speed trips. A solution might be found by battling inside the air cleaner, or by creating a plenum chamber, which would take up more space in an already crowded area under the seat.

Power transmission is accomplished by straight-cut gears from the crankshaft to the clutch. The gears themselves seemed reasonably quiet on our test machine except under load, when they whined a bit. But an alarming clatter sets in when the machine is in neutral with the clutch engaged. Withdrawing the clutch lever quiets things down to a whisper, which would indicate that the clutch unit itself is loose on the transmission shaft, or that there is too much back and forth movement of the transmission mainshaft itself. Since our test machine was an early production model and the similar-in-design HI has little such noise, we can expect that production models will be cured of this annoying fault.

The clutch itself is a model of perfection. In spite of slightly stiff lever pressure, which will be lessened by 30 percent in production models, it took up the drive smoothly and positively every time, and several blistering runs through the clocks hardly affected it. A series of rubber cushion blocks in the rear wheel smooths out the engine’s power impulses and helps increase rear chain and transmission life.

The transmission is practically a carbon copy of the HI unit and features ball bearings on the input sides and needle bearings on the output sides of the shafts. Beefy gears are moved back and forth by short, stout selector forks which girdle a cylindrical shifting drum. The gearshift pedal is connected to the shifter shaft by a linkage system which affords a short lever throw, but the selector detent spring is a little too strong, necessitating heavy pedal pressure for downshifting. Upshifting was a pleasure, however, and the ideally spaced gear ratios get progressively closer as one shifts up, making it easy to keep the engine on the boil when riding through hilly swervery.

Like its larger brother, the S2 is somewhat “tail-heavy,” with 57 percent of its weight on the rear wheel. It is also decidedly “pipey.” Power delivery is very smooth from the minimum recommended engine speed of 3000 rpm right up to just below 6000 rpm. At the latter figure, however, the S2 really wakes up and starts to move. Whacking the throttle full on in low gear produced fantastic “wheelies” and made the machine slightly difficult to control right off the line during the acceleration tests.

When the HI was introduced, a great amount of lip service was given to the benefits of the then revolutionary Capacitive Discharge Ignition system. In spite of the advantages of the high secondary voltage available to the spark plug and a very short rise time, some of the earlier His experienced trouble with the “magic black boxes,” and some distributor problems were also encountered. The latest Hls have improved components, and troubles have been few. So why does the S2 use a more conventional coil and battery ignition? The reason is simple: cost! The CDI system is very expensive; installing it on the S2 would have increased the price of the machine nearly S100! In its place, three separate sets of conventional breaker points allow ultra-precise ignition timing, which may be checked with a strobe light, and ordinary ignition coils which are relatively inexpensive to replace. The AC generator’s output is rectified back to DC to charge the battery and operate the lights. With this system, there is no commutator or brushes to wear out, and it is smaller in size and weight than a DC generator.

Starting the S2 is a snap, whether the engine is hot or cold. The folding kickstarter spins the engine over remarkably rapidly, and the engine often begins running before the kickstarter has traversed half its arc. Even though the crank folds, it is not quite enough to keep the rider’s leg from hitting it while sitting on the machine at a stoplight. Here again, a change is being made for later production models.

In spite of the fact that the S2’s crank throws are set 120 degrees apart, and the engine is a two-cycle which gives the same number of firing pulses as a four-stroke Six, there is some vibration in the 6000-6500 rpm range, and then way up the scale near 8000 rpm. The handlebars are mounted in a firm rubber, which takes most of this annoyance from the rider’s hands, but a tingle is felt through the footpegs at the above mentioned speeds. Happily, this vibration period begins at just above 70 mph, which is the legal maximum speed limit in most states. Our test bike’s wildly optimistic speedometer showed a considerably higher speed.

Throttle response was excellent from idle right up to maximum revs as long as the twistgrip was opened progressively from low rpm. The quick-acting twistgrip requires about a half-turn from idle to full throttle, and dumping the throttle on at engine speeds below 3000 rpm produced sluggish performance, accompanied by “four-stroking” and misfiring. This little engine loves to rev, and shouldn’t be lugged around town.

Braking, too, is slightly improved over the HI in terms of sheer stopping power and control. Considerable lever pressure is necessary to slow the bike from high speed, but “feel” is somewhat better, and the rear brake is nearly ideal in terms of pedal effort. Fading of both brakes accompanied the second and third panic stops during braking tests, however. >

KAWASAKI 350 S2

The front forks, although quite solt ly sprung, give an excellent ride. Rebound damping is also quite good and the machine does not have a tendency to “pogo” when negotiating a fast, badly paved corner. As is the fashion these days, the front fork springs are located inside the fork tubes, and the exposed portion of the tubes is kept clean by rubber wipers, which also keep dirt and grit from damaging the oil seals. For two-up riding, we would prefer slightly stiffer springing.

Rear suspension units, too, are excellent. Our biggest gripe about the rear »suspension units often found on Japanese machines has been the woeful lack of adequate rebound damping, which causes all sorts of weird things to happen at speed, exactly when you need the best control. The S2’s rear suspension units are right up to par. and the spring rate is easily adjustable to compensate for a heavy rider or a passenger.

The 3.00-18 front and 3.50-18 rear Japanese Yokohama tires both have a rear tire tread pattern (which seems to be the vogue these days) with the tread extending well down into the sidewall area to allow high cornering angles. The tires also have a rather soft compound for improved traction, which we wouldn’t consider trading for a few more miles of tread wear. They stick.

Despite a hefty weight of nearly 350 lb., the S2 deceptively feels like a good 1 25 while threading through traffic, and is as sure-footed as many larger machines through high speed curves. Even though it is slightly “tail heavy,” the front end only felt light when accelerating hard in first and second gears, which made accelerating at steep cornering angles from low speeds a very delicate operation. We found it helpful to set the steering damper so that it gave a slight drag. This was sufficient for all our riding, even over badly surfaced roads.

Styling of the S2 is definitely “mod.” The gracefully valanced front fender is attached to the fork tubes by a single bracket on each side. The 3.7-gal. fuel tank is met at the rear

by a sumptuous, wide and soft seat, which terminates into the rear fender/tai 11 ig^ht assembly. These three items are fabricated from steel, while the side covers are formed of fiberglass.

Everything but the frame and headlight brackets is painted a deep red and accented by blue and orange strips. The mufflers are swept up rakishly which improves the appearance and the cornering ability because they won’t scrape the ground. Their high mounting position, however, makes the passenger’s footpegs rather high too. Thus, a long-legged passenger will find his legs cramping after only a short time.

The frame is a smaller version of the HI unit. It features a wide lower cradle to support the engine which extends rearward and upward to just in front of the top rear suspension mounting points. A top cradle supports the seat and extends forward, beneath the gas tank, and terminates in the steering head as do the lower cradle ends. An additional support runs from the steering head down to a crossbrace between the top cradle members. Heavy gusseting around the swinging arm mounting area obviates flexing while cornering, and the swinging arm itself is very strong looking. Engine mountings are substantial as well, and overall quality of the welding and finish is good.

Riding position of the S2 is very comfortable, with a medium-rise handlebar and neutrally placed footpegs. The seat is quite wide and proved to be comfortable for long stretches, and the rear passenger seat rail, affixed to the rear portion of the seat, is much handier than the popular grab strap across the seat. Said strap is usually located under the rider’s backside, which makes it difficult for a passenger to use it for support! All the controls are well placed, with the turn signal switch, horn button and headlamp dimmer on the left grip assembly, and the “starter lever” (choke control) on the right assembly. The ignition switch is located between the speedometer and tachometer, and the front fork lock provided will operate with the front wheel turned either right or left.

So there you have it. Kawasaki’s 350 Three is a delightful hot-rod that will most certainly be a popular and sought-after machine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

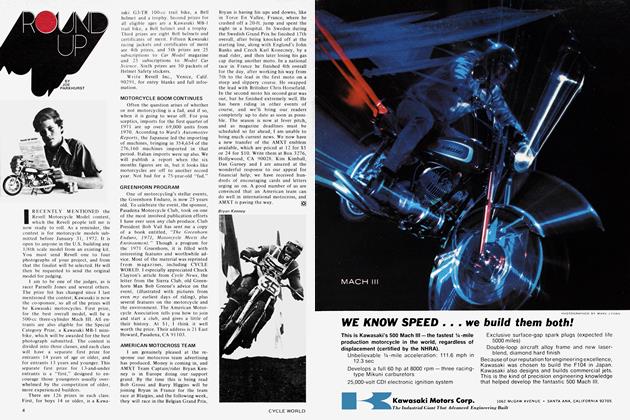

DepartmentsRound Up

SEPT 1971 1971 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

SEPT 1971 1971 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Dept

SEPT 1971 1971 By Jody Nicholas -

Departments

DepartmentsFeedback

SEPT 1971 1971 -

Technical, Etc.

Technical, Etc.Balancing the Mighty Multi

SEPT 1971 1971 By Gary Peters, Matt Coulson -

Features

FeaturesIt's A Steal

SEPT 1971 1971 By Joseph E. Bloggs