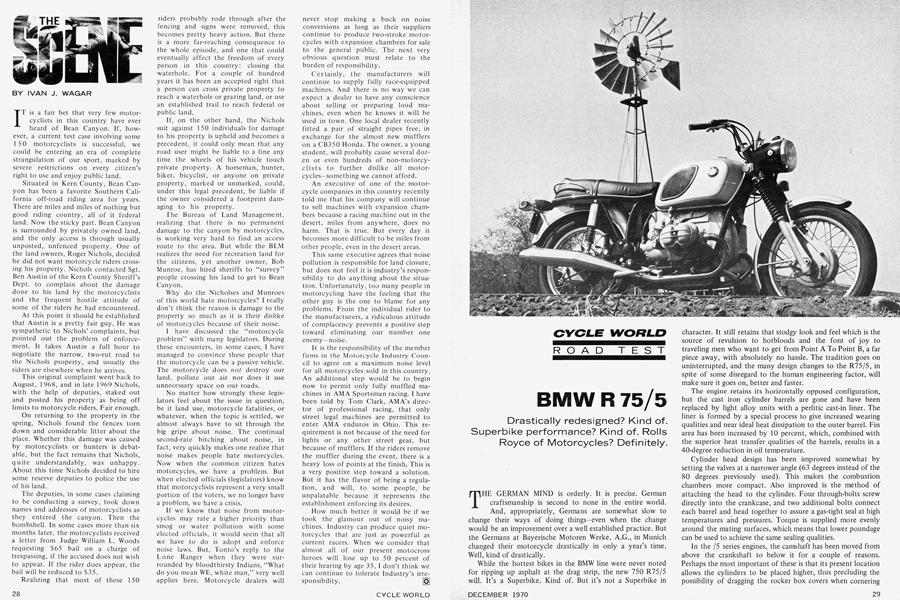

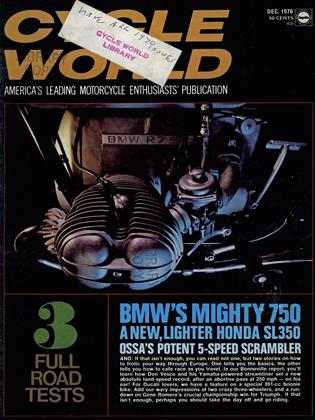

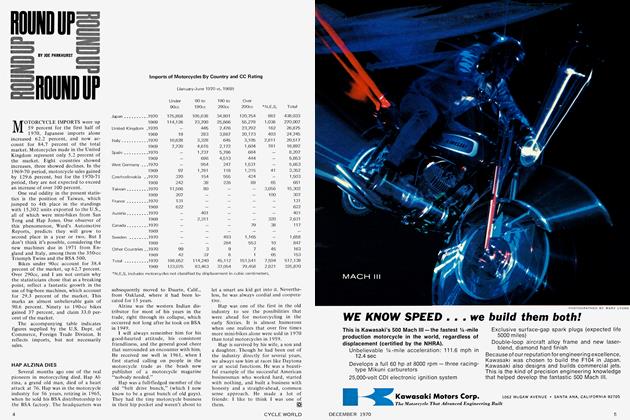

BMW R 75/5

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

Drastically redesigned? Kind of. Superbike performance? Kind of. Rolls Royce of Motorcycles? Definitely.

THE GERMAN MIND is orderly. It is precise. German craftsmanship is second to none in the entire world. And, appropriately, Germans are somewhat slow to change their ways of doing things—even when the change would be an improvement over a well established practice. But the Germans at Bayerische Motoren Werke, A.G., in Munich changed their motorcycle drastically in only a year’s time. Well, kind of drastically.

While the hottest bikes in the BMW line were never noted for ripping up asphalt at the drag strip, the new 750 R75/5 will. It’s a Superbike.. Kind of. But it’s not a Superbike in

character. It still retains that stodgy look and feel which is the source of revulsion to hotbloods and the font of joy to traveling men who want to get from Point A To Point B, a far piece away, with absolutely no hassle. The tradition goes on uninterrupted, and the many design changes to the R75/5, in spite of some disregard to the human engineering factor, will make sure it goes on, better and faster.

The engine retains its horizontally opposed configuration, but the cast iron cylinder barrels are gone and have been replaced by light alloy units with a perlitic cast-in liner. The liner is formed by a special process to give increased wearing qualities and near ideal heat dissipation to the outer barrel. Fin area has been increased by 10 percent, which, combined with the superior heat transfer qualities of the barrels, results in a 40-degree reduction in oil temperature.

Cylinder head design has been improved somewhat by setting the valves at a narrower angle (63 degrees instead of the 80 degrees previously used). This makes the combustion chambers more compact. Also improved is the method of attaching the head to the cylinder. Four through-bolts screw directly into the crankcase, and two additional bolts connect each barrel and head together to assure a gas-tight seal at high temperatures and pressures. Torque is supplied more evenly around the mating surfaces, which means that lower poundage can be used to achieve the same sealing qualities.

In the /5 series engines, the camshaft has been moved from above the crankshaft to below it for a couple of reasons. Perhaps the most important of these is that its present location allows the cylinders to be placed higher, thus precluding the possibility of dragging the rocker box covers when cornering hard with today’s improved tires, which allow greater lean angles than ever before possible. Another advantage is better lubrication to the cam lobes and followers.

Defying the BMW tradition of having no chains in their twin-cylinder motorcycles, the /5 series all use an automotivetype, silent-running duplex chain to drive the camshaft. A plastic-coated tensioner blade acts as a vibration damper, and the flywheel end carries the new Eaton system oil pump.

A totally new crankshaft is employed. It is now a one-piece forging with exceptional bending and flexing resistance. Bearing dimensions are the same as on BMW’s 2.8-liter automobile engine—that is, hefty. Following automotive practice, the main bearings are now of the plain, three-layer variety, using bronze, lead and indium.

Pistons and rings have been changed, too, with a thin, chromium-plated top ring, a shouldered ring in the middle and an equal chamfer ring at the bottom for positive oil control. These thinner rings have less tendency to “flutter” at high engine speeds.

Plain bearings have a greater load-carrying capacity than roller bearings of the same size, but they require a copious supply of oil to carry away the extra heat generated in performing their task. This is accomplished by the use of an Eaton-type oil pump which is a four-lobed eccentric rotor revolving in a five-chambered housing. At 6000 rpm, the pump circulates 212 gal. of oil per hour through the engine. This means that the entire contents of the oil sump passes through the bearings some 355 times every hour.

A large-capacity oil filter is used and features a full-flow pressure-relief valve. The pressure regulating valve is placed downstream from the filter so that only filtered oil may pass back into the engine. Crankcase breathing is accomplished through an anti-turbulence chamber and then to a diaphragm valve in the intake manifold, where a vacuum is present, assuring the proverbial cleanliness of BMW engines.

Carburetion on the R75/5 is accomplished by using two Bing 32-mm constant pressure carburetors. They depend on manifold vacuum, engine speed, and the opening of a butterfly valve to control the raising of the slide, which is connected to a tapered pin. Raising the slide increases the cross section of the ring and allows fuel to emerge from the atomizer jet, but only as fast as the engine can use it.

Hence, it is impossible to flood a properly adjusted carburetor of this type by “blipping” the throttle too vigorously. Fresh air is admitted to the carburetors through an anti-turbulence chamber which houses a large, paper-element air filter. It is conceivable that the restrictions posed by such a “rat-maze” could have an adverse effect on performance, but BMW felt that silent running (from squelching the intake roar) was more important. And a power output of 57 bhp figures out to 76 bhp per liter, which is quite good. Our only objection to the carburetors is their proximity to the rider’s shins. There just wasn’t any way to keep that sensitive part of one’s anatomy far enough away to prevent a painful knock, short of planting one’s posterior on the passenger’s portion of the saddle. And if you’re carrying a passenger, be prepared to suffer.

To gild the lily, BMW installed an electric starter, presumably for the American market. The unit develops a healthy 0.5 hp and is capable of spinning the engine over rapidly, even in sub-freezing temperatures. It is housed on top of the engine, and the resulting increase in engine height makes the engine look bigger than it should to some onlookers. A repeat lock prevents the starter from being actuated once the engine is running, saving the flywheel gear teeth and the starter gear from damage.

Electrical chores are handled admirably by a crankshaftmounted 12-V, 200-watt, three-phase Bosch alternator. Even at idle, when the charging control light goes off, there is sufficient power to begin charging the battery. AC current from the alternator is rectified to DC by diodes, and a mechanical contractor is used as a voltage regulator.

Featuring modern, thin-plate construction, the battery is rated at a healthy 18 amp/hr. and provides a cold start current of 65 amps.

One of the most vehement criticisms of earlier BMWs was the clutch/transmission unit. An inordinately heavy flywheel was used in an effort to keep the engine as smooth as possible. But, in order to allow the constant-mesh transmission to shift noiselessly, an excessive delay was necessary for the engine to slow down enough for the flywheel surface and clutch surface to reach approximately the same speed. Our last test BMW, a 1968 R 60US (CW July, 1968), was notoriously noisy and cumbersome in shifting because of the aforementioned flywheel, which made it necessary to wait a few seconds before attempting a shift. Happily, BMW has seen fit to reduce the weight of the flywheel proportionately with the increased size of the engine, so smooth, rapid shifts were the rule rather than the exception on this machine. But it still is noisy.

The automotive-type, single-disc dry clutch is a model of perfection. Clutch lever pressure is very light, and the assuredness with which the clutch takes up the drive is astounding. The last thing one would expect from a BMW is a “wheelie” when one is banging a shift into second gear. But that’s what we got. Scaareee! Even after several runs at the drag strip, the clutch needed little adjustment and continued its job with very little initial slippage. The clutch unit is splinecoupled to the gearbox, as in previous models.

Closer gear ratios are featured in the redesigned transmission which also aid in smooth shifting. Gear pinion teeth are wider to cope with the increased power of the engine, and an all-new Palloid-pattern crown wheel is featured. A vibration damper on the mainshaft, a taper dog engagement and an eccentric selector fork are notable features.

Final drive remains basically unchanged. A drive shaft running in an oil bath is enclosed within the right-hand swinging arm member. A universal joint is used at the transmission output shaft to compensate for the swinging arm’s up-and-down movements. Changes in length of the drive shaft are compensated for by curved, helical teeth in an internally splined coupling shaft.

Also new is the main frame which has been reduced some 10 lb. in weight over the previous models. Taper-drawn oval tubes were introduced to the motorcycle industry some 30 years ago by BMW, and are once again used in the /5 series frames. The relatively low-slung oval tube backbone intersects the twin tubes of the cradle just behind the steering head, and the complete assembly is reinforced by long welded seams and gusset plates to form an exceptionally rigid unit in all planes.

Slight flexibility in the longitudinal plane, a desired feature, is still present and the lightweight rear end structure which supports the dual seat carries bolt-on mountings for the upper ends of the suspension struts. Weight of the frame is now a light 29 lb.

The telescopic front fork, first developed by BMW in 1933 and adapted to their production models in 1935, was replaced in 1954 by the Earles, leading-link fork. This fork possessed excellent suspension characteristics with surprisingly fast reaction to road irregularities. But the leading-link front fork had a serious disadvantage in that it had heavy steering as a result of the large mass of the main fork stanchions which lay well ahead of the pivot axis of the steering. A low-frequency wobble was apt to occur at low speeds, while at high speeds a large castor angle and a hydraulic steering damper were necessary to tame the fork reactions.

Although an amazing 8.4 in. of fork travel is claimed for the new telescopies, the fork spring length is so short that the forks lose almost half their travel when the machine is moved off the center stand. Add the weight of even one rider and they collapse even further, leaving only about 3.5 in. of travel available for impact. And the travel for the rebound stroke is, in our estimation, mostly wasted. Under normal riding conditions, the forks would not bottom, but under heavy braking they did with a resounding thump. A longer spring with perhaps a bit higher poundage rating would improve the front suspension immeasurably.

Rebound damping, on the other hand, was considered nearly ideal, and the fork legs feature lengthy fork leg sides to increase the wearing properties. Careful location of the sliding tubes offer what is claimed to be a reaction superior to the leading-link unit in encountering road irregularities. An additional benefit is a weight reduction of six pounds over the Earles-type fork.

At the rear of the machine, the suspension units are excellent and feature a three-way, spring-rate adjustment by means of a lever. Rear suspension travel has been increased from 4.1 in. to 4.9 in.

Pre-loaded taper roller bearings support the swinging arm member and are easily adjusted with the aid of a torque wrench.

Redesigned brakes add to the overall newness of the machine. Although they are slightly smaller in swept area than the previous units, a slightly larger diameter imparts a feeling of security to the rider when braking down from 80 mph or so in a panic-stop situation. Strong, straight spokes connect the hubs to newly designed alloy rims, with a reduced section size and an increase in strength. Tire sizes of 3.25-19 front and 4.00-18 rear provide the required amount of stopping and going traction. Fiberglass fenders add to the reduction in overall weight, with the front fender brace doing double-duty as a fork brace.

Big it looks and big it is. With a curb weight of 457 lb. the BMW is certainly no lightweight, but it doesn’t pretend to be. An illusion of largeness is created by the curiously humped fuel tank, which would be much more attractive if the top were flatter. Finish is up to traditional BMW standards. Welds are almost mathematically perfect, and paintwork is outstanding. Our test bike was finished in the famous German Rennsilber and never failed to catch an envious glance at every corner. German chrome needs no comment.

Everything seemed to fit perfectly with beautifully matched engine castings, cylinders, cylinder heads and rocker box covers. Allen screws abound on the machine, and the most complete tool kit we’ve seen contains almost everything needed to perform any work short of an overhaul. The toolbox is located in a heavy plastic tray under the seat, with ample room inside for spare light bulbs, road maps and a set of marbles or two.

The seat is one of the most comfortable we’ve seen, and the passenger portion seems almost orthopedic. It couldn’t be better, and can be locked to protect the tool kit.

An increasingly rarer item is also found beneath the seat: a tire pump that actually works! Another nice touch is the beautiful cast-aluminum turn signals, and spring (not split) lockwashers abound everywhere.

Riding the R75/5 is quite an experience. Vibration is felt only when accelerating hard at low engine rpm, particularly in high from 40 to 50 mph. But this becomes practically negligible at higher engine speeds. Of course, the torque reaction from the longitudinally mounted crankshaft is still present to a marked degree when blipping the throttle, and the rear end tends to rise markedly under hard acceleration and sink under deceleration. But handling and general road manners are very good. We liked the mechanical and exhaust silence which has been synonymous with BMW for decades, and high speed handling qualities make it possible to dive into turns much faster than one would think. Pushing hard through a turn is'easy, but it’s hard to forget that you’re riding a big machine.

Defects are few in number, in our estimation, but are inexcusable when one considers that BMW took the time to design a new machine. As we have mentioned, the position of the carburetors made stop-and-go riding painful to the shins. The problem is more pronounced with a passenger aboard because this forces the rider to sit more forward on the seat. Regarding the carburetor’s function, we would prefer to have smaller (physically), slide-type carburetors to keep our shins from looking like those of a hockey player. Another minor complaint arose from the positioning of the turn signal switch. It was difficult to operate without shifting one’s grip on the throttle, which had very stiff return springs on our test machine.

Rubber handlebar grips are supposed to be comfortable, but the BMW’s are not. They are hard and transmit vibration, causing a tingling sensation in the hands after riding for 50 miles or so.

Instrumentation is very complete with the speedometer and tachometer being contained in the same instrument. Although the speedometer was reasonably accurate, it tended to fluctuate slightly at certain speeds. But the tachometer looked as though it had an acute case of Saint Vitus’s dance at normal highway speeds. Neutral indicator, oil pressure and high beam indicator lights are all located within the single instrument, and a large green light on the top, left-hand side of the headlamp blinks when a turn signal is flashing.

Performance is certainly up to what is expected of a Superbike. A standing quarter-mile of 13.89 with a terminal speed of 91.27 mph is nothing to be sneezed at coming from such a docile, long-winded machine. And a top speed of 108.23 mph with the engine not fully broken-in is quite good. It will run all day at 80 to 90 mph. Overall gas mileage worked out to a figure of 42 mpg, which could improve as the engine loosens up.

In spite of its drawbacks, the BMW must still hold claim to the reputation, “The Rolls Royce of Motorcycles.”

BMW R 75/5

List Price $1848

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

December 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

December 1970 By Jody Nicholas -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

December 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Features

FeaturesEuropean Touring

December 1970 By Stephen J. Herzog -

Features

FeaturesAnd Now...The Case For Traveling Light

December 1970 By Dan Hunt