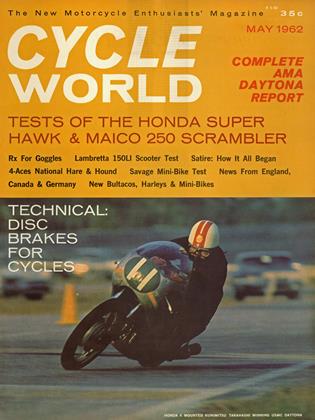

HONDA SUPER HAWK

Cycle World Road Test

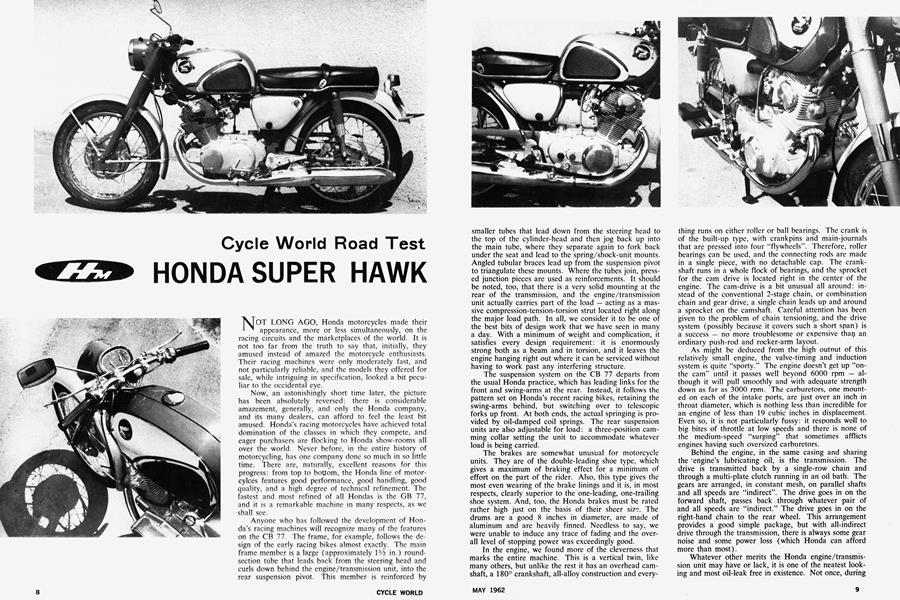

NOT LONG AGO, Honda motorcycles made their appearance, more or less simultaneously, on the racing circuits and the marketplaces of the world. It is not too far from the truth to say that, initially, they amused instead of amazed the motorcycle enthusiasts. Their racing machines were only moderately fast, and not particularly reliable, and the models they offered for sale, while intriguing in specification, looked a bit peculiar to the occidental eye.

Now, an astonishingly short time later, the picture has been absolutely reversed: there is considerable amazement, generally, and only the Honda company, and its many dealers, can afford to feel the least bit amused. Honda's racing motorcycles have achieved total domination of the classes in which they compete, and eager purchasers are flocking to Honda show-rooms all over the world. Never before, in the entire history of motorcycling, has one company done so much in so little time. There are, naturally, excellent reasons for this progress: from top to bottom, the Honda line of motorcylces features good performance, good handling, good quality, and a high degree of technical refinement. The fastest and most refined of all Hondas is the GB 77, and it is a remarkable machine in many respects, as we shall see.

Anyone who has followed the development of Honda’s racing machines will recognize many of the features on the CB 77. The frame, for example, follows the design of the early racing bikes almost exactly, The main frame member is a large (approximately 1 Vi in.) roundsection tube that leads back from the steering head and curls down behind the engine/transmission unit, into the rear suspension pivot. This member is reinforced by smaller tubes that lead down from the steering head to the top of the cylinder-head and then jog back up into the main tube, where they separate again to fork back under the seat and lead to the spring/shock-unit mounts. Angled tubular braces lead up from the suspension pivot to triangulate these mounts. Where the tubes join, pressed junction pieces are used as reinforcements. It should be noted, too, that there is a very solid mounting at the rear of the transmission, and the engine/transmission unit actually carries part of the load — acting as a massive compression-tension-torsion strut located right along the major load path. In all, we consider it to be one of the best bits of design work that we have seen in many a day. With a minimum of weight and complication, it satisfies every design requirement: it is enormously strong both as a beam and in torsion, and it leaves the engine hanging right out where it can be serviced without having to work past any interfering structure.

The suspension system on the CB 77 departs from the usual Honda practice, which has leading links for the front and swing-arms at the rear. Instead, it follows the pattern set on Honda’s recent racing bikes, retaining the swing-arms behind, but switching over to telescopic forks up front. At both ends, the actual springing is provided by oil-damped coil springs. The rear suspension units are also adjustable for load: a three-position camming collar setting the unit to accommodate whatever load is being carried.

The brakes are somewhat unusual for motorcycle units. They are of the double-leading shoe type, which gives a maximum of braking effect for a minimum of effort on the part of the rider. Also, this type gives the most even wearing of the brake linings and it is, in most respects, clearly superior to the one-leading, one-trailing shoe system. And, too, the Honda brakes must be rated rather high just on the basis of their sheer size. The drums are a good 8 inches in diameter, are made of aluminum and are heavily finned. Needless to say, we were unable to induce any trace of fading and the overall level of stopping power was exceedingly good.

In the engine, we found more of the cleverness that marks the entire machine. This is a vertical twin, like many others, but unlike the rest it has an overhead camshaft, a 180° crankshaft, all-alloy construction and everything runs on either roller or ball bearings. The crank is of the built-up type, with crankpins and main-journals that are pressed into four “flywheels”. Therefore, roller bearings can be used, and the connecting rods are made in a single piece, with no detachable cap. The crankshaft runs in a whole flock of bearings, and the sprocket for the cam drive is located right in the center of the engine. The cam-drive is a bit unusual all around: instead of the conventional 2-stage chain, or combination chain and gear drive, a single chain leads up and around a sprocket on the camshaft. Careful attention has been given to the problem of chain tensioning, and the drive system (possibly because it covers such a short span) is a success — no more troublesome or expensive thap an ordinary push-rod and rocker-arm layout.

As might be deduced from the high outout of this relatively small engine, the valve-timing and induction system is quite “sporty.” The engine doesn’t get up “onthe cam” until it passes well beyond 6000 rpm — although it will pull smoothly and with adequate strength down as far as 3000 rpm. The carburetors, one mounted on each of the intake ports, are just over an inch in throat diameter, which is nothing less than incredible for an engine of less than 19 cubic inches in displacement. Even so, it is not particularly fussy: it responds well to big bites of throttle at low speeds and there is none of the medium-speed “surging” that sometimes afflicts engines having such oversized carburetors.

Behind the engine, in the same casing and sharing the ’engine’s lubricating oil, is the transmission. The drive is transmitted back by a single-row chain and through a multi-plate clutch running in an oil bath. The gears are arranged, in constant mesh, on parallel shafts and all speeds are “indirect”. The drive goes in on the forward shaft, passes back through whatever pair of and all speeds are “indirect.” The drive goes in on the right-hand chain to the rear wheel. This arrangement provides a good simple package, but with all-indirect drive through the transmission, there is always some gear noise and some power loss (which Honda can afford more than most).

Whatever other merits the Honda engine/transmission unit may have or lack, it is one of the neatest looking and most oil-leak free in existence. Not once, during

the entire testing schedule, did a single drop of oil appear on the outside of the casing. In fact, there was so little oil even from the engine breather (which is supposed to be a chain lubricator) that the rear chain was running dry, and it was necessary to squirt some oil at it to prevent rusting. Ah well, perhaps when our test bike gets old (it has 3500 miles behind it at the conclusion of our testing) it will have enough blow-by to push some oil onto the chain. Seriously, we were happy to trade the chore of an occasional look at the chain for the oil mist that surrounds all too many engines.

In common with most other Japanese motorcycles, the Honda has an electric starter. It is bolted to the front of the crankcase and twirls the engine over by means of a chain drive and an over-riding clutch. The power for the starter is provided by a 12-volt, 9-ampere/hour battery with a glass (or clear plastic, we’re not sure) case. By removing one of the tool-box/aircleaner covers, one can check the electrolyte-level very quickly. There are two fiber filter air-cleaners, and these are an enormous aid to prolonging the life of an engine.

The control layout is exceptionally well thought out: The handlebars are flat and low — as they should be on a racing/touring bike — and there are three mounting positions for the foot-pegs. Ordinarily, the pegs would be located in the forward mounts, but it is very little work to move them. The peg on the right side carries the brake-lever and its actuating cable, and it can be moved around quite freely without even disturbing the brake adjustment. On the left, (the shifting side) the foot-peg carries the shift-lever, but a longer push-pull rod would have to be substituted before the peg could be moved. However the pegs are set, the CB 77 is comfortable, and the riding position affords a high degree of control.

In getting started on chilly mornings, we were glad to have the electric starter (the emergency kick-starter had been removed from our test machine). Although the Honda has a very efficient “choking” set-up, it proved to be quite “cold-natured” and did a great deal of burbling and wheezing for the first few moments of running. At no time was this a real problem though and once, when we stupidly left the tail-light on all night and found ourselves with a flat battery, we managed a push-start after running no more than thirty feet. In short, the super-tuned Honda engine may complain a bit, but it never fails to run.

Even though it has a decidedly smallish engine, the Super Hawk bangs down the road in a fashion that would astonish the “big-inch” fanciers. Using a maximum of 9200 rpm — the valves clatter outrageously at anything above that — we were able to record a standingstart 1/4-mile of 16.8 seconds. That might not sound like much to you drag-bike fans, but for a stock, fully road-equipped, 305 cc-engined motorcycle with rather “tall” road-racing style gearing it is phenomenal. Moreover, it does the trick with no fuss at all: lots of throttle and bang, bang, bang through the gears for a less than 17-second 1/4 mile. Not fast enough to humble the big twins, but enough to be exciting and a lot of fun.

Even better than the acceleration was the top speed, which averaged-out at nearly 105 mph. The makers claim a top of 110, and we couldn’t get that, but we had the feeling that a razor-sharp CB 77 with stronger valve springs than our test bike was blessed with, and a less bulky rider than our six-foot-plus test rider, might make good the claim. In any case, the speed we got was good enough to give the Honda a fine chance against all comers in a flying-mile contest.

Happily, the CB 77’s road behavior was every bit the equal of its speed potential. As we have said, the brakes are great, and the handling over any surface (except dirt, which we didn’t try) is even better. At any speed, you can lean it down into the turns and really push without getting the feeling that the situation could get out of hand. One cannot adequately describe the handling: it is simply too good. The closest we can get is to say that the rider always feels like an extension of the machine; you don't point it, you simply point yourself and the bike follows your lead.

From any viewpoint, the Honda CB 77 Super Hawk is an exceptional motorcycle. It is technically advanced and possesses a degree of civilization that is certain to make it popular. Such touches as the electric starter, the fine ride and handling, the performance and little things like the easy-to-read speedometer/tachometer combination make this Honda just about irresistible. Our entire staff was deeply impressed by the Super Hawk; the technical editor to such an extent that he is ready to buy one, which may have some special significance, as he is hard-to-please and a mighty cautious man with a dollar as well. •

HONDA

CB 77 SUPER HAWK

$665

SPECI FICATIONS

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

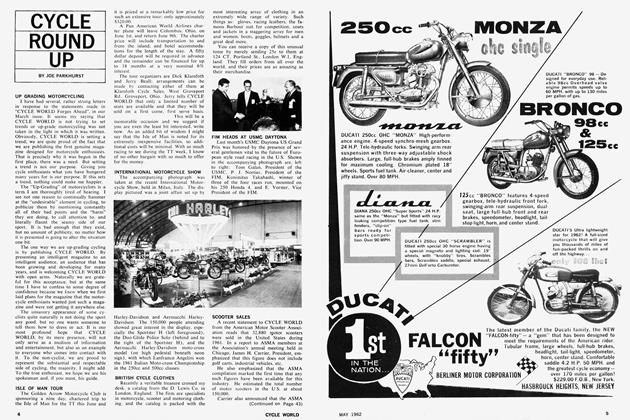

Cycle Round Up

May 1962 By Joe Parkhurst -

The Service Department

The Service DepartmentValve Float

May 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

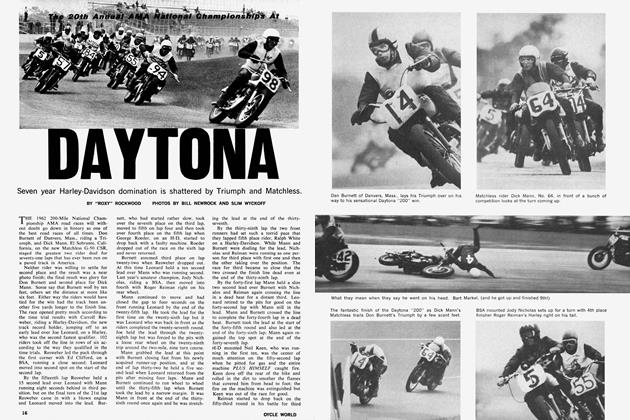

Daytona

May 1962 By "Roxy" Rockwood -

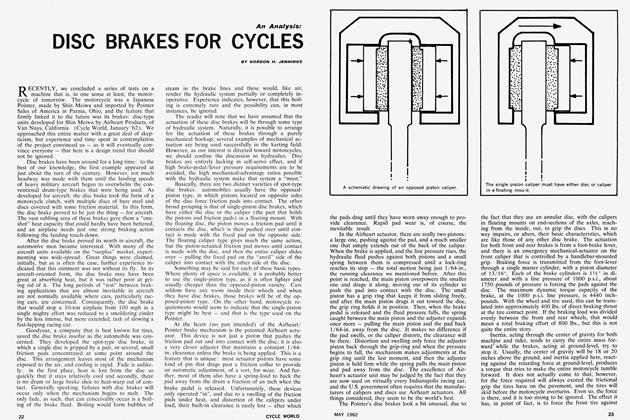

An Analysis

An AnalysisDisc Brakes For Cycles

May 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

Satire

SatireIn the Beginning

May 1962 By Dave Evans -

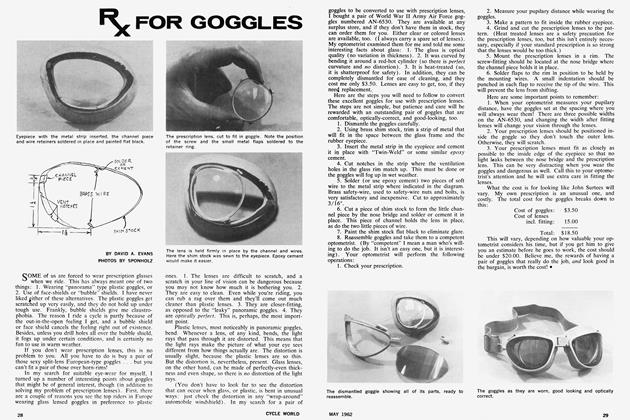

Scooter Test

Scooter TestRx For Goggles

May 1962 By David A. Evans