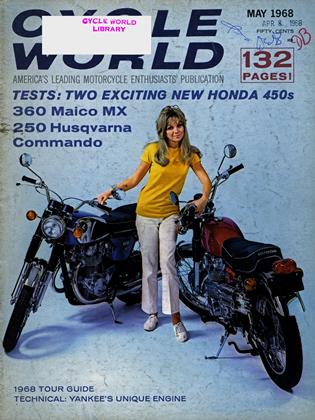

HONDA 450 CB AND CL

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

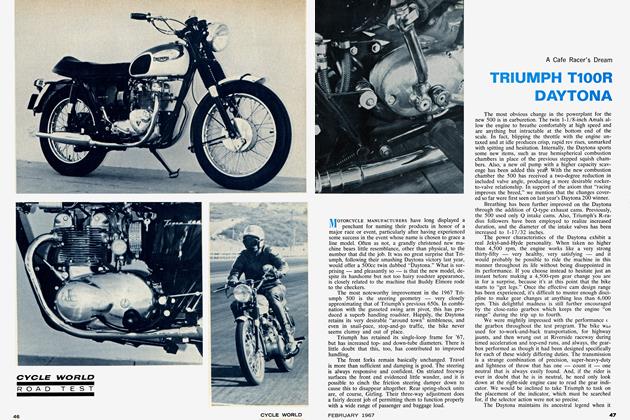

A Stage II Motorcycle Engineered for Export

IN 1965, Honda put on the American market an all-new, large displacement, top-of-the-line motorcycle, the CB 450. For the first time in history, the American enthusiast was offered an alloy dohc vertical Twin in a 100-mph roadster at a list price just over $900. This was a machine that met its competition on better than even terms. It also was a buy that, to Honda’s consternation, was turned down by far too many U. S. motorcyclists. What was to be Honda’s premier machine did not enjoy the portion of the American market that its maker had anticipated it would.

Some reasons for this consumer standoffishness exhibited by Americans must be judged rather petty. Other reasons for rejection by a large market segment were decidedly major.

An unusually high, humped fuel tank, though of road racing configuration, unfortunately gave the original CB 450 a rather topheavy, stodgy appearance, out of keeping with the machine’s potential, that straightaway put off a number of prospective buyers. And, in 1965, the name Honda, to a great many younger, less knowledgeable enthusiasts implied small displacement machinery; few even wished to believe that Honda produced anything of greater significance than 50-cc road gnats.

Of most detriment to the original Honda CB 450’s desired image, however, were a transmission that was cursed with badly spaced ratios, unacceptable to the hard-core enthusiast, and carburetion that hindered performance with erratic fuel delivery—thus rough, stumbling transition of engine speed from idle to top rpm.

These problems may well be related to Honda’s decision to withdraw from participation in world grand prix racing. Not faced with the week-to-week, hour-to-hour demands of competition, Honda research and development people were given freedom to pursue modification of the firm’s products for domestic and export markets. Over past months, though news of the company’s retirement from racing was not made public, Honda product planners and engineers were given breathing space, a respite from the fury of forced improvement of the GP breed, in which to re-design the firm’s entire touring line, including 250-, 350-, and 450-cc displacement models.

This breather has resulted in not one, but two second-generation Honda 450s—the sleek, contemporary CB roadster, and the flippant CL street scrambler. If any machines in Honda’s new product lineup can dispell the memory of that stodgy appearance, can shatter the “Honda-is-a-small-bike” image, this pair of 450s can. These are motorcycles that exude visual appeal, a revitalized large bore image, and exhibit what well-considered engineering can do to evolve a distinctly improved product.

Most important modification among those that differentiate the new Honda 450 from the old is an all-new, friction-free five-speed transmission. This gearbox carries evenly spaced ratios which provide for maximum effective use of the engine’s broad power band.

This magnificent transmission’s mainshaft and countershaft rotate in needle and ball bearings; the live ends retain ball bearings, while the dead ends now turn in needles, rather than bushings.

Where the original 450’s shifter drum displayed two cam grooves and two forks, the new transmission’s shifter drum shows three cam grooves-and three sliding gears. The arrangement accommodates the additional gear. A redesigned detent mechanism improves location of neutral, and makes for more positive gear selection.

The five-speed transmission is fitted with a sliding gear on the folding crank kick starter. This gear completely disengages from the countershaft first gear when not in use. Previously, an idler gear was in constant engagement. Obviously, the new arrangement reduces superfluous drag on the powerplant.

The five-speed gearbox is much more complex, thus much more costly to manufacture than its earlier counterpart. Though this new creation has one additional gear, it produces a great deal less total gear and bearing friction—drag—which previously robbed the engine of a portion of its horsepower potential.

One circumstance that will prove a drawback, at least in the minds of early 450 owners, is that the five-speed gear cluster is not interchangeable with its four-speed counterpart. The extra gear requires wider case and wider spaced case mounting points.

Power is transmitted through a seven-plate clutch which bears great resemblance to the original 450 clutches. However, the initial clutch assemblies were fitted with six springs. The new clutches carry only four springs, but individual spring tension is heavier, and total pressure is equal.

The renewed 450 engine is served by a pair of 32-mm Keihin Seiki constant velocity carburetors, which appear identical to the units which were fitted to the first 450s. However, where there were once two pinhole orifices adjacent to each throttle butterfly, there now are four. These are four fuel discharge jets to control slow speed mixture. An idle jet is situated downstream from the butterfly. The No. 1 slow speed discharge jet is adjacent the butterfly. The No. 2 slow speed discharge jet is upstream slightly from the butterfly. The No. 3 slow speed discharge jet is situated a hair’s breadth upstream from No. 2. Honda engineers report that an overwhelming amount of design and testing time resulted in the super-critical location of these orifices. As the throttle twist grip is turned, the butterfly plates of the carburetors progressively uncover these tiny jet openings. Fuel is delivered into the air stream in such a manner that a mixture of the required richness is drawn into cylinders over the full range of the rpm curve. No sudden leanness, with accompanying erratic behavior, is now encountered.

A casual observer would believe the Stage II Honda 450 engine to be identical to the original powerplant. This is far from the case.

Piston dome and combustion chamber shapes have been altered to raise the compression ratio from 8.5 to 9.0:1, and to increase squish area. A smaller diameter electric starting motor delivers higher output. The Honda’s previous plunger-type self-scavenging oil pump has been redesigned to insure unrestricted oil flow. Internal oil cooling fins have been cast into the lower crankcase half. External fins are denser for improved cooling.

In the eider engine, all four main bearings were supported into the upper case by hold-down studs. In the new engine, inner main bearings are supported against the upper half by bearing caps and studs; outer mains now are secured between the two case halves. The new configuration neither strengthens the engine, nor reduces bearing drag, but simplifies manufacture through elimination of one milling sequence, while at the same time permitting closer tolerances to be maintained during line boring operations.

Valve diameter is increased; and valve seat pressures also have been raised. However, camshaft bearings, tappets and tappet clearances, and other top end components of the dohc system are shared with the first-run 450 engines. The central chain camshaft drive remains unaltered.

Combustion chamber and valve modifications have resulted in an output boost from 43 bhp at 8500 rpm, claimed for original 450s, to 45 bhp at 9000 rpm for the new machines. First generation machines were capable of a solid 102 mph top speed and 15.2-sec. quarter-mile e.t.s. The new 450s, as accompanying acceleration graphs show, can achieve significantly better marks.

Redline on the 1968 version of the engine is 9700 rpm. At this figure, mean piston speed is a shade over 3600 ft./min., which is somewhat higher than that of the majority of racing engines. It is a testimonial to Honda engineering and assembly processes that this ultra-high rpm machine is in no way temperamental.

The glossy alloy powerplant rests within a single downtube cradle frame that, from a distance, appears a copy of its forerunner. Closer inspection shows that some welded tube bracing on the rear suspension strut has been replaced by welded pressed steel gussets.

The new CB and CL are fitted with conventional telescopic hydraulic forks—that now carry neoprene gaiters. The rear suspension coil springs, now chromium plated and exposed, rather than shrouded, are three position adjustable with a special wrench supplied with each machine.

The jounce/rebound cycle of these rear coils is damped by a very special type of shock absorber. Unlike the first 450s, which were fitted with conventional telescopic hydraulic units, in which metered passage of oil through valves in a piston inside a cylinder accomplished the damping operation, the new machines have been given De Carbon type shock absorbers.

De Carbon units are comprised of two concentric cylinders in which are a conventional piston with a two-way valve, and a special free piston with an O-ring seal. The upper piston, fixed to the chassis by a pivoting piston rod, moves up and down within the oil-filled cylinder as the rear wheel encounters irregularities in the roadway. A closed rubber chamber at the bottom of the oil-filled cylinder contains nitrogen gas under high pressure. Movement of the reciprocating piston against the oil moves the fluid through valves in the piston in the conventional manner. The free piston—with no valves and an oil-tight seal to the walls of the cylinder—moves upward as the reciprocating piston moves in the like direction. Expansion of the nitrogen in the chamber at the bottom of the tube forces the rubber bag upward to follow closely the free piston. Thus the volume of oil displaced by motion of the piston is adjusted by movement of the free piston and associated expansion of the gas-filled chamber. Expansion of the pressurized inert gas prevents cavitation and aeration of oil between the free piston and the nitrogen chamber. Honda engineers say the system provides a high inertia value for damping out unwanted spring action, while generating little actual inertia, to accomplish damping action with minimal mechanical and seal friction.

The Hondas’ 8-in. twin leading shoe front brake units proved fully adequate to meet all traffic situations. The rear brakes of the CB and CL delivered what was considered more than adequate stopping capability for machines of the 500-600 lb. all-up weight category.

So much for the mechanicals. More than a little aesthetic consideration goes into design, assembly, and purchase of motorcycles. The aesthetics of the new crop of Honda 450s are outstanding.

Visually, pleasure in the CB and CL starts with the exceedingly fine finish. Application of paint is flawless. Chromium plating is deep with reflective luster. Welds and machined parts bear the mark of careful craftsmanship. These Honda hallmarks can only please and satisfy an owner.

The visual appeal of the CB model is that it offers everything a present day roadster requires—a touring style fuel tank, twin low sweeping silencers that function as well as carry a title, and a saddle that looks as comfortable as it is. Gone is the single instrument cluster; the 450s carry both speedometer/odometer and tachometer in black resilient plastic protective cases—attractive and businesslike. Amber turn signal lamps, front and rear, accent the black, chromium and tank laquer color.

The CL, in reality the CB in sports casuals, carries a smaller fuel tank, and high-rise exhaust pipes sweeping upward and rearward at the left side of the machine to terminate in a boxlike silencer. Rider and passenger legs are shielded from exhaust heat by tandem metal guards. (One of these heat shields vibrated loose and was lost during testing; Honda engineers would well employ lock wire at securing points.) And, the CL is fitted with a rather straight, motocross sort of handlebar in place of the more curving, elevated bar given its roadster kinsman. The CL is fitted with a sports tread tire at both front and rear. All these trim modifications add up to an aura of open country, trail and mountains for the CL, yet do nothing to impair what is, in final essence, Honda’s top product—a 450-cc touring machine.

In performance, there is little to choose between the two models. Differences between CYCLE WORLD’S two test machines were, for all practical purposes, insignificant. The CL street scrambler was a bit quicker off the line and up to the eighth-mile mark. The CB roadster was capable of slightly higher top speed. The latter perhaps is attributable to the CL’s more restrictive silencer on the high-rise exhaust pipes. The CB’s large diameter silencers, while maintaining a very reasonable sound level, did not inhibit top end performance of the roadster.

Both models carry the Honda electric starter. The best recommendation for this feature is that it was with regret that test crewmen returned to kick-’em-and-go motorcycles. The Hondas’ kick starters were employed once or twice for test purposes—and cold engines came to life with no more than three prods.

The two machines, set up with those slight trim differences, each present a slightly different feel. Various riders expressed preference for one or the other of the machines as being the most comfortable. Satisfaction in the motorcycles boiled down to individual likes and dislikes in regard to riding position.

With either 450, cross-town riding is a breeze, effortless, nothing short of pure pleasure. A flick of the left foot, almost unnoticed by the rider, selects the proper ratio for slow-and-go trickling, or the quick transit from light to light. A Detroitbuilt automatic wouldn’t make it any less difficult.

On the freeways, the 450s cruise at 65 mph with the engine turning at a relatively relaxed, middle-of-the-torque-curve 5700 rpm. For passing, a snapped downshift to fourth gear, and a brisk rotation of the throttle punches the machine ahead with something akin to rocketry. Two-up riding, one of the great pleasures of large displacement ownership, doesn’t dampen the spirits of the 450 engine. Either machine is capable of an honest, illegal, 105 mph, plus.

However, these Hondas, both roadsters, are at their exciting best where city becomes country, where eight lanes degenerate to two, where straights become bends, and where flatlands rise into the hill country. Test riders continually sought “the long way around,” or “the scenic route,” in preference to the shortest distance from A to B, just for the sheer excitement of running a sweet machine over the territory it was designed to conquer.

The second generation Honda 450s must be regarded not as reworkings of the original, but as new machines well designed, well engineered, well manufactured, and well aimed at a specific market—the U.S., and Canada, where 450s will be identical.

Well aimed, means better aimed this time. Concentration on export products, rather than on super high performance road racing machinery, has resulted in attention to detail—those new tanks, that gearbox, that effective carburetion and such niceties as plastic coating on the clutch and brake levers so they won’t feel cold to the rider’s hands on a winter’s morning. Attention to detail can only result in sales success for the CB and CL 450s.

HONDA

450 CB

CL

$957

$1035

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Round Up

May 1968 By Joe Parkhurst -

The Service Department

May 1968 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1968 -

The Scene

May 1968 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Ruin To Record

Ruin To RecordOut of the Rubble of World War Ii Came the Nsu Twin of Wilhelm Herz — the First Motorcycle To Break 200

May 1968 By Richard C. Renstrom -

Fiction

FictionThe Pickup

May 1968 By Robert Ricci