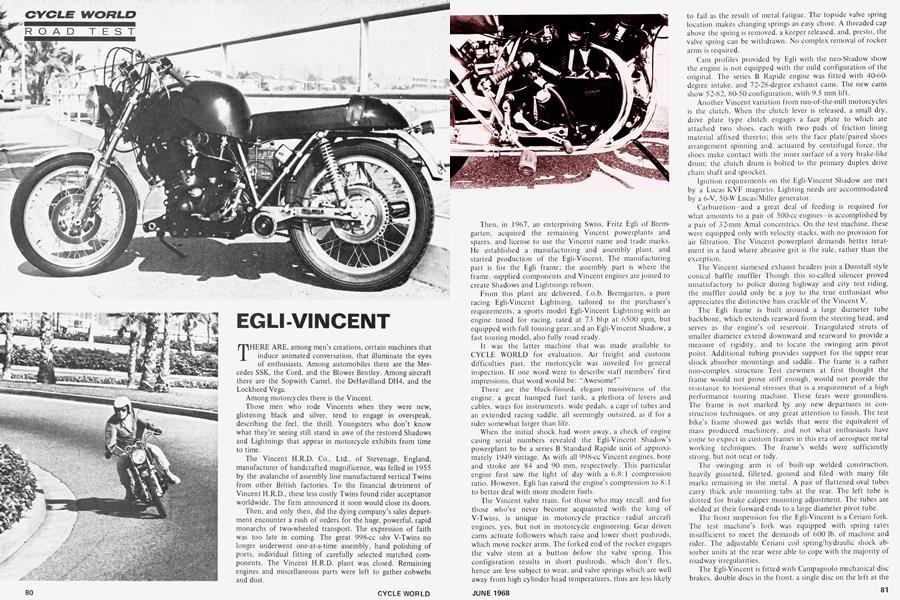

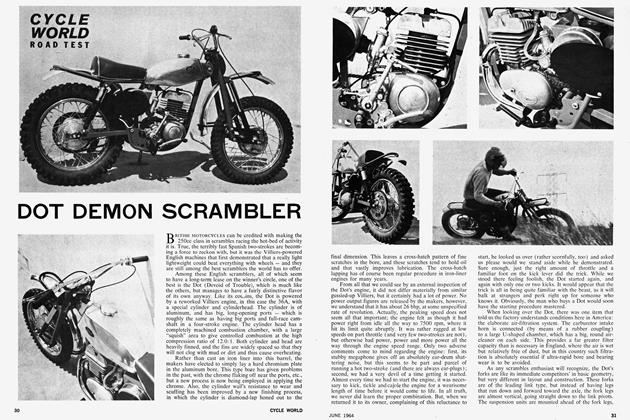

EGLI-VINCENT

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

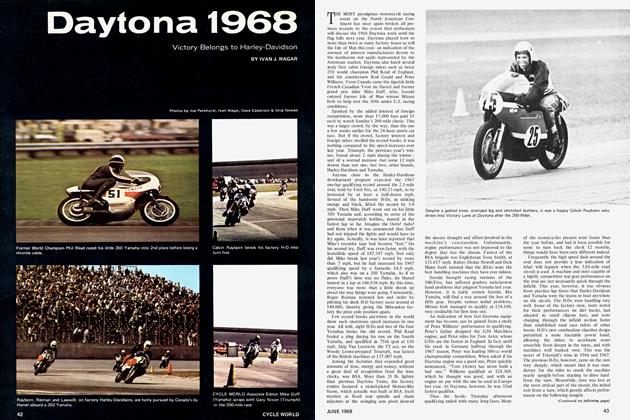

THERE ARE, among men's creations, certain machines that induce animated conversation, that illuminate the eyes of enthusiasts. Among automobiles there are the Mercedes SSK, the Cord, and the Blower Bentley. Among aircraft there are the Sopwith Camel, the DeHavilland DH4, and the Lockheed Vega.

Among motorcycles there is the Vincent.

Those men who rode Vincents when they were new, glistening black and silver, tend to engage in overspeak, describing the feel, the thrill. Youngsters who don’t know what they’re seeing still stand in awe of the restored Shadows and Lightnings that appear in motorcycle exhibits from time to time.

The Vincent H.R.D. Co., Ltd., of Stevenage, England, manufacturer of handcrafted magnificence, was felled in 1955 by the avalanche of assembly line manufactured vertical Twins from other British factories. To the financial detriment of Vincent H.R.D., these less costly Twins found rider acceptance worldwide. The firm announced it soon would close its doors.

Then, and only then, did the dying company’s sales department encounter a rush of orders for the huge, powerful, rapid monarchs of two-wheeled transport. The expression of faith was too late in coming. The great 998-cc ohv V-Twins no longer underwent one-at-a-time assembly, hand polishing of ports, individual fitting of carefully selected matched components. The Vincent H.R.D. plant was closed. Remaining engines and miscellaneous parts were left to gather cobwebs and dust.

Then, in 1967, an enterprising Swiss. Fritz Egli of Bremgarten, acquired the remaining Vincent powerplants and spares, and license to use the Vincent name and trade marks. He established a manufacturing and assembly plant, and started production of the Egli-Vincent. The manufacturing part is for the Egli frame; the assembly part is where the frame, supplied components and Vincent engines are joined to create Shadows and Lightnings reborn.

From this plant are delivered, f.o.b. Bremgarten, a pure racing Egli-Vincent Lightning, tailored to the purchaser’s requirements, a sports model Egli-Vincent Lightning with an engine tuned for racing, rated at 73 blip at.6500 rpm, but equipped with full touring gear; and an Egli-Vincent Shadow, a fast touring model, also fully road ready.

It was the latter machine that was made available to CYCLE WORLD for evaluation. Air freight and customs difficulties past, the motorcycle was unveiled for general inspection. If one word were to describe staff members’ first impressions, that word would be: “Awesome!”

There are the black-finned, elegant massiveness of the engine, a great humped fuel tank, a plethora of levers and cables, wires for instruments, wide pedals, a cage of tubes and an extended racing saddle, all seemingly outsized. as it for a rider somewhat larger than life.

When the initial shock had worn away, a check of engine casing serial numbers revealed the Egli-Vincent Shadow’s powerplant to be a series B Standard Rapide unit of approximately 1949 vintage. As with all 998-cc Vincent engines, bore and stroke are 84 and 90 mm, respectively. This particular engine first saw the light of day with a 6.8:1 compression ratio. However, Egli has raised the engine’s compression to 8:1 to better deal with more modern fuels.

The Vincent valve train, for those who may recall, and for those who’ve never become acquainted with the king ot V-Twins, is unique in motorcycle practice—radial aircraft engines, yes, but not in motorcycle engineering. Gear driven cams actuate followers which raise and lower short pushrods, which move rocker arms. The forked end of the rocker engages the valve stem at a button below the valve spring. This configuration results in short pushrods, which don’t flex, hence are less subject to wear, and valve springs which are well away from high cylinder head temperatures, thus are less likely to fail as the result of metal fatigue. The topside valve spring location makes changing springs an easy chore. A threaded cap above the spring is removed, a keeper released, and, presto, the valve spring can be withdrawn. No complex removal ot rocker arms is required.

Cam profiles provided by Egli with the neo-Shadow show the engine is not equipped with the mild configuration of the original. The series B Rapide engine was fitted with 40-60degree intake, and 72-28-degree exhaust cams. The new cams show 52-82, 80-50 configuration, with 9.5 mm lift.

Another Vincent variation from run-of-the-mill motorcycles is the clutch. When the clutch lever is released, a small dry, drive plate type clutch engages a face plate to which are attached two shoes, each with two pads of friction lining material affixed thereto; this sets the face plate/paired shoes arrangement spinning and, actuated by centrifugal force, the shoes make contact with the inner surface of a very brake-like drum; the clutch drum is bolted to the primary duplex drive chain shaft and sprocket.

ignition requirements on the Egli-Vincent Shadow are met by a Lucas KVF magneto. Lighting needs are accommodated by a 6-V, 50-W Lucas/Miller generator.

Carburetion-and a great deal of feeding is required for what amounts to a pair of 500-cc engines-is accomplished by a pair of 32-mm Amal concentrics. On the test machine, these were equipped only with velocity stacks, with no provision for air filtration. The Vincent powerplant demands better treatment in a land where abrasive grit is the rule, rather than the exception.

The Vincent siamesed exhaust headers join a Dunstall style conical baffle muffler Though this so-called silencer proved unsatisfactory to police during highway and city test riding, the muffler could only be a joy to the true enthusiast who appreciates the distinctive bass crackle of the Vincent V.

The Egli frame is built around a large diameter tube backbone, which extends rearward from the steering head, and serves as the engine’s oil reservoir. Triangulated struts of smaller diameter extend downward and rearward to provide a measure of rigidity, and to locate the swinging arm pivot point. Additional tubing provides support for the upper rear shock absorber mountings and saddle. The frame is a rather non-complex structure. Test crewmen at first thought the frame would not prove stiff enough, would not provide the resistance to torsional stresses that is a requirement of a high performance touring machine. These fears were groundless. The frame is not marked by any new departures in construction techniques, or any great attention to finish. The test bike’s frame showed gas welds that were the equivalent of mass produced machinery, and not what enthusiasts have come to expect in custom frames in this era of aerospace metal working techniques. The frame’s welds were sufficiently strong, but not neat or tidy.

The swinging arm is of built-up welded construction, heavily gusseted, filleted, ground and tiled—with many file marks remaining in the metal. A pair ot flattened oval tubes carry thick axle mounting tabs at the rear. The left tube is slotted for brake caliper mounting adjustment. The tubes are welded at their forward ends to a large diameter pivot tube.

The front suspension for the Egli-Vincent is a Ceriani tork. The test machine’s fork was equipped with spring rates insufficient to meet the demands of 600 lb. of machine and rider. The adjustable Ceriani coil spring/hydraulic shock absorber units at the rear were able to cope with the majority ot roadway irregularities.

The Egli-Vincent is fitted with Campagnolo mechanical disc brakes, double discs in the front, a single disc on the left at the rear. Test crewmen agreed unanimously that brake pedal and hand lever effort was excessive, and that braking efficiency left something to be desired. In an effort to increase efficiency of the braking mechanism, the manufacturer has bolted 2-in. extensions on the existing Campagnolo front brake actuating levers—while not repositioning brake cable ferrule retainers above the levers. This places the brake cable stress point rearward from the ferrule bearing point. When hand lever tension is applied, the result is biting drag at the ferrules, and excessive cable wear. The best of brakes, with the ultimate in easy stopping capability, should be standard—no, mandatoryon a machine that is capable of 130 mph.

Alloy rims, 19 in. in diameter front and rear, carry Avon road racing style tires.

The Egli-Vincent Shadow’s instrumentation is comprised of suspiciously Volkswagen-like VDO trip odometer/speedometer, tachometer (which confusingly reads counterclockwise), and an oil temperature gauge mounted in a crudely finished alloy bracket atop the handlebars. An ammeter is located almost out of sight of the rider in the top of the headlamp.

The Egli-Vincent was taken to Riverside Raceway, the 2.7-mile Southern California circuit, for final testing. Loafing around the course, at speeds of 80 mph or less, the machine proved surprising. It handled well, much better than anticipated. Though somewhat top heavy, the big machine clung to the road in bends something closely akin to road racing fashion. Once leaned over in a bend, the rider was required to pick up the machine bodily to make a straight line exit.

Speeds well in excess of 100 mph were achieved without difficulty. A flat-out run was not attempted, however, because of the braking capabilities of the machine in relationship to the running room available.

Over the quarter-mile, the Egli-Vincent, even though it was apparently running overly rich, and even though it was ridden with care in deference to its owner, proved itself capable of consistent 94-mph trap speeds, with e.t.s in the low 14s. The legendary Vincent V-Twin is as strong as ever.

Though ride, handling and performance of the Egli-Vincent Shadow were deemed adequate, close inspection showed a number of things wrong, definitely out of order with this particular machine.

Oil leakage became a messy problem, the result, apparently of faulty seal insertion. Smoke and exhaust gasses escaped past the exhaust header clamps, perhaps because a copper ring gasket was missing or too tightly compressed. Apparently no seal had been fitted on the generator gearshaft at the top of the primary case. These difficulties looked to CYCLE WORLD staffers to be results of lack of pains taken in assembly, rather than faulty original design. Exercise of more care could but result in a much more acceptable motorcycle.

A 250 lb. behemoth cannot kick the Vincent engine’s starting crank downward against compression. The trick is to tickle the carburetors to overflow (Vincents like a lot of gas); release compression with the left-hand lever, feel (with an educated foot) when the No. 1 (rear) piston is just ready to reach the firing stroke; start the downward kick; flick in the compression release; repeat anywhere from three to 11 times for a start. Once the technique is learned, the Egli-Vincent starts hard-but it starts.

What place has the Egli-Vincent in the present world of motorcycling? The neo-Shadow has a niche, and that is ownership by a man who is first a connoisseur of Vincents, second a lover of motorcycling, and third a mechanic/machinist of greater than average skill. An Egli-Vincent must be appreciated, well loved and well maintained. *

EGLI-VINCENT

$2000