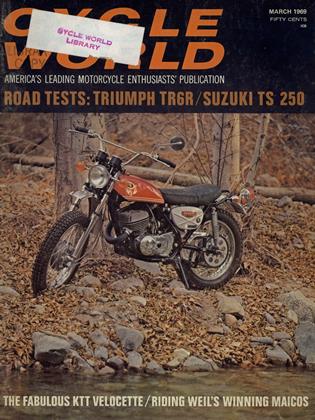

SUZUKI TS-250 SAVAGE

A Sometimes Trail Bike For The Back Street Sneak

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

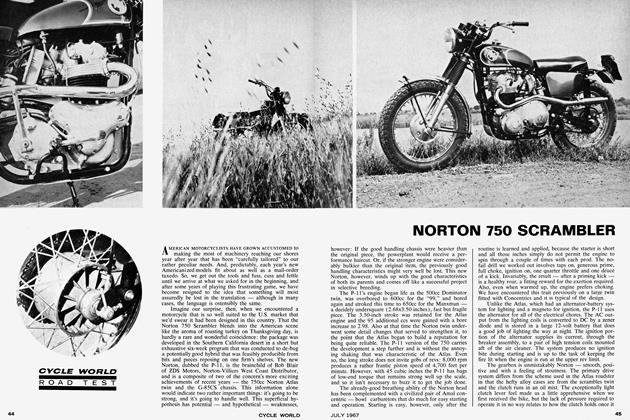

IT’S ATTRACTIVE. Chrome and blinker/reflector doodads abound. Give the engine a few hundred miles to loosen up, and it puts out an astonishing amount of broad range power. Were it not for the fact that it looks so stylized, Suzuki’s new TS-250 Savage could pass for a serious dirt bike. But it is the best Japanese dual purpose street and trail 250 ever tested by CW.

Despite superficial resemblances to the TM-250 motocrosser made by Suzuki, the Savage is a much different machine, and is not intended for the rider with racing intentions. Rather, it is a bike for the casual enthusiast, who likes to sneak through the back streets of town to the fire roads or open land. Fortunately, the bike is street legal to the Nth degree, and quiet, so the sneaking will be done only in principle rather than necessity.

It is an extremely pleasant machine to ride on the pavement and, surprisingly, doesn’t do at all badly once it hits the dirt. Front/rear weight bias, fairly even percentages at 45/55, makes it amenable to smooth road sliding, but excessively frontheavy for rapid travel across rough terrain. Wheelbase is nearly 54 in., which contributes greatly to the Savage’s stability.

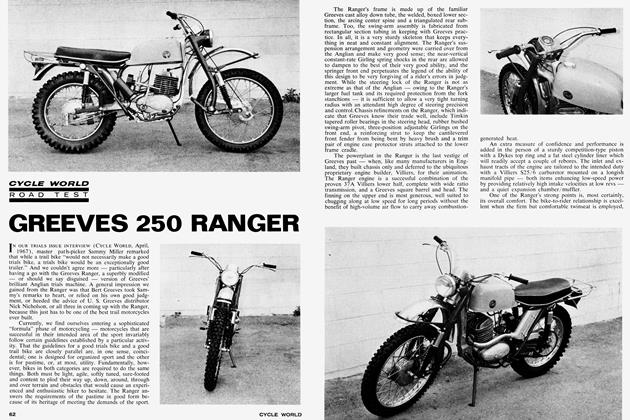

The frame and swinging arm assembly seem amply rigid. Of classical single top tube, single downtube and double cradle configuration, and resembling that of the TM-250, the Savage’s frame has a robust look to it. That “look” is partly the tubing size, partly the compact, rigid-looking main frame loop, and partly the gussets and strut that strengthen the steering head. The swinging arm shows no signs of flexing, although this might not remain the case if the engine were brought to motocross tune.

The front fork, finished in chrome from top to bottom, greatly enhances the appearance of the machine. Travel is 6.5 in., which is an exemplary amount of telescopic action even for a pukka dirt racer fork. However, there is no damping on the rebound phase, which reduces stability and steering precision over rough ground and causes front wheel patter in heavy braking. The fork also clanks when the front end is yanked into the air and the fork legs extend unchecked to the stops. The clanking sound itself is harmless, though it tends to discourage the rider from “leaving it on.” Compression phase of the fork action is excellent. Three-way adjustable shock absorber units at the rear master their duties well. The result is an exceptionally comfortable ride in the dirt, as well as willingness of the machine to slip over ledges and bumps without jarring the rider. An increase in steering lock would be welcome, however. The present stops provide very little, and the condition is extremely annoying when side-sliding down hill, sharply countersteering, or when turning slowly in tight quarters, trials style.

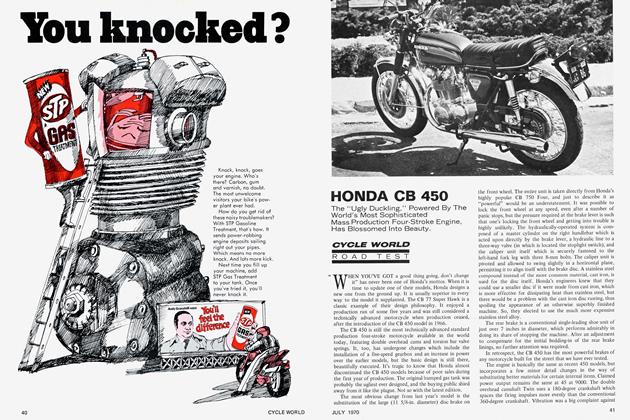

The strong point of Suzuki’s new trail machine is its engine. It is a two-stroke Single that bears some resemblance to the TM-250 motocross racer. This likeness has mainly to do with the bore/stroke dimensions, and finning, after which differences appear in the gearbox, ratios, carburetion, compression ratio, piston design, and method of lubrication. That choice of bore and stroke—66 by 72 mm—has a curious story behind it, one that is rather a monument to Japanese eclecticism. Those dimensions, not coincidentally, are identical to those of the old Villiers Starmaker engine. The Suzuki Savage inherited them from the TM-250 which picked them up from the Greeves Challenger, which seemed, to the Japanese, a good machine to emulate at the time—which was when Suzuki began experimenting with motocross racing in Europe about five years ago. Ironically, the recent Greeves had these dimensions forced upon them, first because the manufacturer, of necessity, had to buy engines from Villiers, and later, when Greeves started to make its own engines, because of the need to rely on the proven Alpha crankshaft design with its 72-mm stroke. The new Challenger 250s will sack this longish stroke in favor of a more modern oversquare design. The last laugh is Suzuki’s, however, for the new Savage engine, with its “old hat” bore and stroke, puts out more beans, in mild tune, than the old Villiers concern ever dreamed possible.

Suzuki rates the Savage at a conservative 23 bhp. In the offing is a go-fast kit to raise the output to 31 bhp for fast cross-country work. Unlike the motocross engine, which uses premixed gas and oil, the TS-250 engine uses Suzuki’s Posi-Force system that employs metered oil injection to obviate the traditional two-stroke chore of mixing oil and gasoline. In this system, an external Une carries oil to the left-side main bearing. Oil caught in an entrapment disc feeds to a hollow crankpin to lubricate the big end, which throws excess oil into the fuel/air charge. The connecting rod small end receives its lubrication from oil thrown away from the crankpin. The right-side main is fed by clutch gear splash, which drains back to the bottom of the primary case. A separate oil injector at the intake port lubricates the piston skirt. The intake port injector is easy to remove should it be desired to revert to premixing oil and gas with the installation of the power kit. If this were done, and the other part of the injection system left operative, the percentage of oil to gas in the premix would be less than normal.

The Posi-Force system, as tested on the TS-250, seemed quite effective; metering oil in proportion to the amount of throttle opening as it does, it reduces exhaust smoke to a minimum. The external lines appear vulnerable to the hazards of dirt riding, but they are nicely tucked away and held down by neat metal cleats.

Quality of all engine castings is exquisite. They are pressure die cast and the finish is meticulous. Also worth special mention are the seals that maintain crankcase pressure; they have very thin edges in the Suzuki, to keep crankshaft drag to a minimum.

The thick, widely spaced finning of the aluminum alloy cylinder barrel is a welcome feature, reflecting the more serious side of this engine’s heritage. Widely spaced fins are less likely to clog in muddy running. Suzuki says the head fins will be polished on all production machines, though the rough, functional, sand-blasted finish of the fins on GW’s test bike seems preferable. The cylinder head is attached by six head studs. The barrel has four ports—one intake, one exhaust, and two transfer. The dense steel liner is integrally cast. The piston is made of an aluminum-silicon alloy which has a self-lubricating property. It’s a two-ring piston, and the rings are Suzuki’s familiar keystone shape, flat on the bottom and tapered at the top. The ring grooves are squared. The taper allows gas pressure from combustion to work behind the ring and push it outward to form a better seal.

Both big and small ends of the connecting rod are carried in caged needle bearings. This could be construed as overengineering in a 23-bhp engine, but is actually a prudent “hop-up factor,” to accommodate the roughly 40-percent increase in power to be gained with the racing kit.

In its mild tune, the Savage starts quite easily, hot or cold. The VM28SC (28-mm) carburetor is one of Suzuki’s pressure compensating devices that allows the rider to leave the fuel tap open without fear of flooding. The intake airbox is amply sized, and its inlet is located perfectly—just below the seat. Should the bike be used in wet country events, it could be submerged in two and half feet of water and still run, assuming nothing else drowned out. The exhaust pipe, which resembles an expansion chamber, is in reality an effective silencer. It is neatly curved in amidships to allow the rider effective knee grip on the tank without the discomfort of a bulge at his shins. The heat shield appears scanty, but does its job well.

The five-speed constant mesh transmission is a brand new affair that owes nothing to the motocross machines or Suzuki road models. An engine teardown revealed that it is a beautifully robust affair, with generously sized helical primary gears. It offers some rather surprising, high cost features for so inexpensive a machine. There are no bushed bearing surfaces anywhere. The shifter drum rotates on needle bearings. The main shaft and layshaft have generously sized ball bearings on the “live” ends. On the “dead” ends, where some engine manufacturers would leave well enough alone with bushings, Suzuki goes first class with caged needle bearings. The engagement dogs are angled to prevent jumping out of gear.

The result of all this extra expense is that the Savage gearbox is smooth working and virtually foolproof, even when shifting at speed on rough terrain. The six-plate, six-spring clutch is of equal quality, and showed no signs of getting tired, either in the hills or after repeated dragstrip runs. The gear ratios are well spaced, but the overall gearing seems high for anything except pavement and fireroads. In fifth gear, which is best described as an overdrive ratio, the engine is turning less than 6000 rpm at 70 mph, which is extremely comfortable for road riding. But in heavy trailing, first gear is much too tall and provides virtually no engine braking on steep downhill runs. Several additional teeth on the rear sprocket would be welcome. A slightly lower ratio would probably improve the already respectable top speed of 75 mph, as the test bike’s engine was not pulling to its peak horsepower speed with present gearing.

It may seem odd that the Savage weighs but a pound short of 300, for there are some production 500s that weigh close to this. Look carefully, though, for this Suzuki is carrying quite a bit of extra equipment. In addition to headlight, taillight, horn and mirror, the bike also carries a battery, separate speedometer and tachometer, four hefty direction signal light pods, plus junction box and switches for all these electrics. Curb weight could be reduced to a possible 265 lb. with all but the battery removed. The serious trail rider, if he does nothing else, would be wise to remove the signal lights, as these break easily if the bike is dropped. Handling would probably benefit from removal of everything up front (except the speedo for enduros) by shifting the weight bias rearward.

The Suzuki Savage’s trump cards are styling appeal and more than ample horsepower. With the removal of weight, lowering of overall gear ratio, and modification of the front fork, the bike could be made into an effective enduro weapon. Off the showroom floor, it is sleek, reliable, and great fun at a veritable bargain.

SUZUKI TS-250 SAVAGE

$782

SPECIFICATICI

TEST CONDITIONS

PERFORMANCE