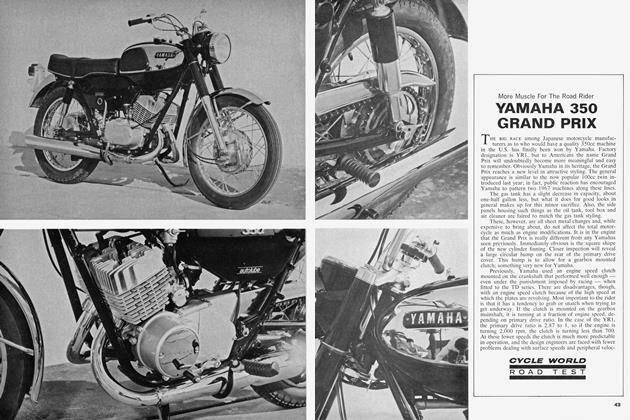

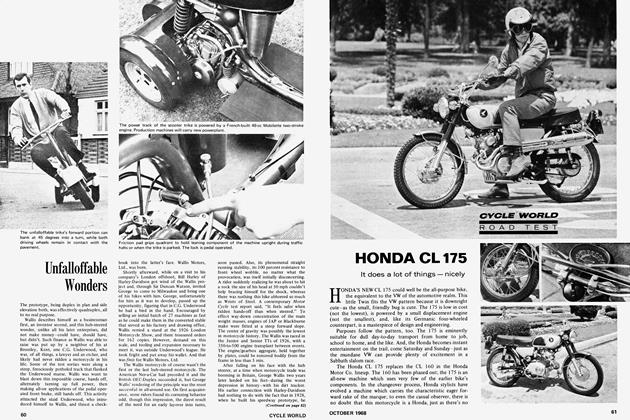

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

Even Hotter Saki

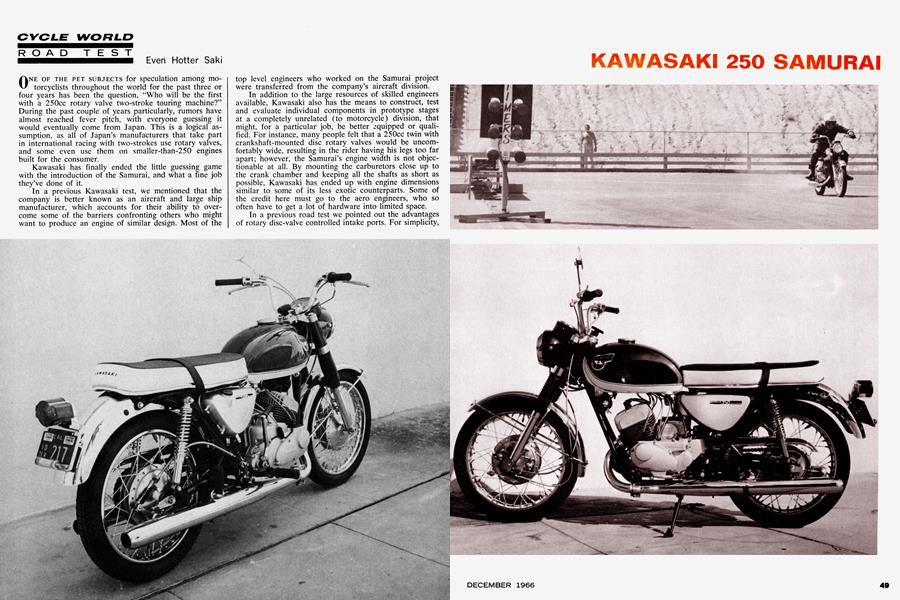

ONE OF THE PET SUBJECTS for speculation among motorcyclists throughout the world for the past three or four years has been the question, “Who will be the first with a 250cc rotary valve two-stroke touring machine?” During the past couple of years particularly, rumors have almost reached fever pitch, with everyone guessing it would eventually come from Japan. This is a logical assumption, as all of Japan’s manufacturers that take part in international racing with two-strokes use rotary valves, and some even use them on smaller-than-250 engines built for the consumer.

Kawasaki has finally ended the little guessing game with the introduction of the Samurai, and what a fine job they’ve done of it.

In a previous Kawasaki test, we mentioned that the company is better known as an aircraft and large ship manufacturer, which accounts for their ability to overcome some of the barriers confronting others who might want to produce an engine of similar design. Most of the top level engineers who worked on the Samurai project were transferred from the company’s aircraft division.

In addition to the large resources of skilled engineers available, Kawasaki also has the means to construct, test and evaluate individual components in prototype stages at a completely unrelated (to motorcycle) division, that might, for a particular job, be better equipped or qualified. For instance, many people felt that a 250cc twin with crankshaft-mounted disc rotary valves would be uncomfortably wide, resulting in the rider having his legs too far apart; however, the Samurai’s engine width is not objectionable at all. By mounting the carburetors close up to the crank chamber and keeping all the shafts as short as possible, Kawasaki has ended up with engine dimensions similar to some of its less exotic counterparts. Some of the credit here must go to the aero engineers, who so often have to get a lot of hardware into limited space.

In a previous road test we pointed out the advantages of rotary disc-valve controlled intake ports. For simplicity, we can eliminate the word “disc,” as all currently produced rotary valve engines use a round, flat disc fixed to the crankshaft. The disc rotates at crankshaft speed and is located in the intake passage between the carburetor and crankcase. A notch is cut in the periphery; its depth is equal to intake port diameter and its length is the desired number of crankshaft degrees for optimum crankcase filling under whatever conditions prevail. Therefore, it can be seen that changes, or adjustments, can be accomplished more easily than with a piston-port engine. More important than simply making the notch larger or smaller is the convenience of being able to have the port open and close exactly when one wishes, whereas with a piston-port the timing is symmetrical. In other words, at whatever point the piston uncovers (or opens) a port on its way up the stroke, it will close the port at the same number of crankshaft degrees on the way down.

KAWASAKI 250 SAMURAI

It can be seen, then, that port height is also critical in the overall sequence of events, and it is because of this fact, plus any intake or exhaust boost one is able to attain with resonant waves, that designers have been successful in getting exceptionally high power output, considering the limitations imposed by symmetrical timing. Therefore, with any given engine, there is optimum port height and this is a further restriction.

All this, of course, is common two-stroke knowledge, and the reason for Kawasaki going directly to what has generally been felt to be the ultimate touring two-stroke design. Rotary valves offer a wider power band for any given maximum power output level than does a pistonport engine. This is mainly due to the absence of complicated resonant waves that are only effective over a rather narrow part of the rev band.

Kawasaki made our road test more interesting than usual by supplying an extra engine to disassemble and use in any way we saw fit. In addition, factory development engineer Mr. Horie gave us complete working drawings and answered any questions we were able to put forth to him. We were concerned, for instance, over the fact that Kawasaki injects oil into the intake port only, rather than a positive feed to the connecting rod big ends through a hollow crankshaft. There has been a feeling among some of us that most of the fuel/oil mixture is inclined to bypass the bottom end when rotary valves are used and the mixture enters from the side of the engine.

Mr. Horie assured us that this is a misconception; the higher the engine speed (and the need for more lubrication), the more complete is the turbulence throughout the crank chamber. Even at engine idle there is still very good “swirl" taking place to thoroughly lubricate all components. The fiber rotary valve requires a high level of lubrication and, by injecting the oil just ahead of the disc. Kawasaki has ensured maximum oil where it is most needed. Fiber is an excellent material for the disc for two reasons: it is light, which is a major consideration with the high rpm capabilities of this engine; also, the fiber becomes oil-impregnated and tends to have somewhat of a reserve oil supply all its own.

To disassemble the engine, one has only to remove the side covers and take the bottom off the engine, as the main castings split horizontally through the four major shaft centers. At this point any shaft can be lifted out individually. Crankshaft end float is controlled by an outside lockring on the drive side main bearing o.d. The gearbox main shaft has a ball bearing on the input side with a needle bearing on the opposite end. The layshaft has a ball bearing on the output and needles at the other end. Both ball bearings (and therefore the shafts) are located in the same manner as those on the crankshaft.

Kawasaki believes that a strong crank assembly is the most important single requirement in any engine, and the one in the Samurai is, indeed, a hefty piece of beautifully machined steel supported by four ball-type main bearings. The center seal, which isolates the crank chambers, is mounted snugly between the two center mainbearings at the point of maximum crank stability, resulting in good seal life. Very little clearance exists anywhere in the crank chamber, the cases being only slightly larger than the crankshaft. Aside from being a desirable feature on two-strokes, small cases also offer maximum mechanical rigidity for any given casting thickness, so the gains are two-fold.

Shouldered one-piece crankpins are pressed into the flywheels and have an eight-ton press fit. The two crank halves are assembled at 12 tons. As with most Japanese motorcycles, all external surfaces of the connecting rods are left as forged and, although the appearance is slightly “cobby,” the “skin" left from the forge is better left alone.

When rotary valves are fitted to the ends of the crankshaft it becomes necessary to find a new location for the generator and ignition points. On the Samurai, everything has been packaged very neatly and put into the air intake casting on top of the engine behind the cylinders; thus, fresh air is passed over the generator and keeps heat to a minimum.

The generator runs at half engine speed and is driven by a helical-cut fiber gear from the primary drive; a full wave rectifier converts the AC output from the generator. Opposite the drive end are two sets of breaker points operated by cams on the generator rotor. An index plate with scribed lines, when lined up with a fixed pointer, corresponds to the ignition point of 23° advance. We checked the timing and found the visual method to be very accurate. Mounting the ignition system in this man ner offers a very definite advantage over something fitted out on the end of a crankshaft, where, because of mass and lack of support, there is often sufficient movement to cause the timing to wander.

The air intake housing surrounding the generator elim inates "two-stroke noise" by having an inherent damping effect. Regardless of how the throttle is operated, there is a complete lack of intake noise, which can sometimes be louder than the exhaust on a two-stroke.

Whether it is due to robust castings, sturdy crankshatt or rotary valves (we suspect all three), the engine runs like a turbine, except at unusually high rpm, at which point minor vibration can be felt through the tank, but never through the seat or handlebars. Although the tem perature only reached the low 50s (°F) in the mornings, the engine always started on the first kick, after advancing the mixture lever. Again, credit must go to the rotary valves, as the Samurai engine does not display any of the sometimes annoying two-stroke idiosyncrasies. Instead, it has the predictability usually associated with and credited to four-stroke designs. - - .

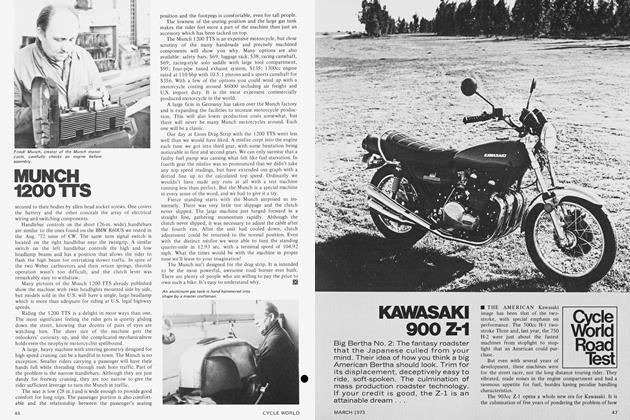

The Samurai is heavy and when being pushed or loaded on a truck it could be mistaken for a larger-than250 machine. Fortunately, it has plenty of horsepower to cope with the weight, and the end result is an exceptional ly sturdy motorcycle. Once underway, the rider is quickly assured that it is a lightweight. It feels light and positive at all times and the handling is excellent. Suspension. front and rear, is quite soft, but very well dampened so as not to cause sponginess or "yawing," often found in touring bikes. A friction-type steering damper is fitted so that steering can be trimmed to suit individual tastes.

Although the front brake feels rather spongy at the lever, it is an excellent stopper - light, progressive and completely capable of carrying out its functions with maxi mum safety. The rear brake is more than adequate for its job.

When highway cruising on the Samurai, particularly with a passenger, it is necessary to down shift to fourth gear frequently, and even third rather often. Actually, this is not unreasonable for a two-fifty and is probably only noticeable because it is so easy to forget that this is a small displacement machine. The engine is simply not up on the power curve in fifth gear at speeds below 80 mph. Both fourth and fifth gears (ratio-wise) are overdrive; that is, internal ratios are less than 1.0:1. All three upper gears are nicely spaced and easily selected, as the gear lever has a short, positive stroke. There is, however, a fairly large gap between first and second that requires the engine be buzzed a bit in first before the shift. Here again, it is only pronounced when carrying a passenger or climb ing a hill. The advantage of having a low first gear, which the Samurai does, more than compensates for the gap be tween first and second gears. We prefer the gap to any of the alternatives available, such as widening the spread in the upper cogs. for instance. - -

Performance-wise the Samurai is a match for most motorcycles around, regardless of displacement. The fac tory claims a 15.1 second quarter-mile. We were unable to reach this figure with our 160-pound test rider; how ever, we do feel it is not an unreasonable claim as all CYCLE WORLD tests are carried out with a half-tank of gas and our tester is convinced that with less fuel and a rider of lesser weight. say 140 pounds, the factory figure can be obtained easily. - -

The Samurai we received for test was not a proto type. but an actual off-the-line machine and taken from the first dealer shipment to arrive in the U.S. Therefore, it can be better evaluated for finish and appearance than a one-off special tailored for the press. The finish is of an unusually high standard throughout, particularly the en gine/transmission castings. both internally (crankcham bers especially) and externally. High luster, maroon paint enhances an already attractive tank that blends well with the overall design. Both fenders are chromed and the rear one is wider than normal, which will minimize the amount of road "2orp" thrown onto the passenger's back.

Our test machine has not been cleaned during the seven-hundred-odd test miles and the engine is completely free of oil leaks. Thanks to the air intake arrangement, there is no trace of mixture film often found deposited all over the rear of a two-stroke engined machine. We can definitely say that the Samurai is a fine motorcycle in every respect.

KAWASAKI

250 SAMURAI

SPECI FICATIONS

$695

PERFORMANCE