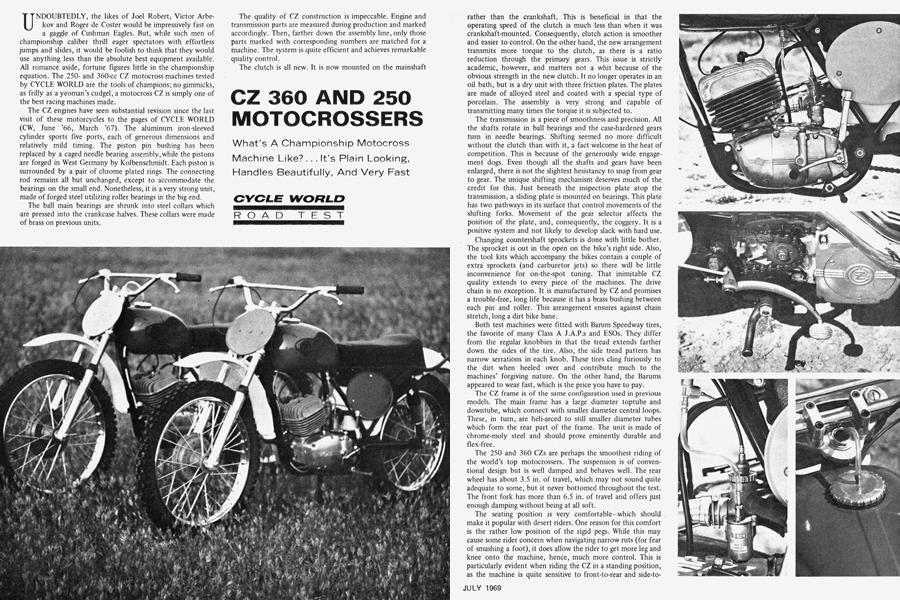

CZ 360 AND 250 MOTOCROSSERS

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

What’s A Championship Motocross Machine Like? ... It’s Plain Looking, Handles Beautifully, And Very Fast

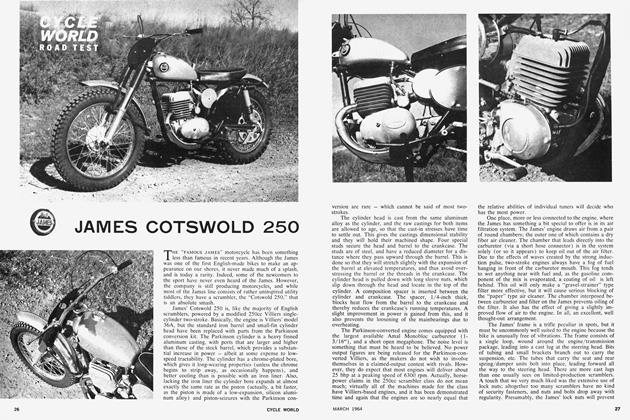

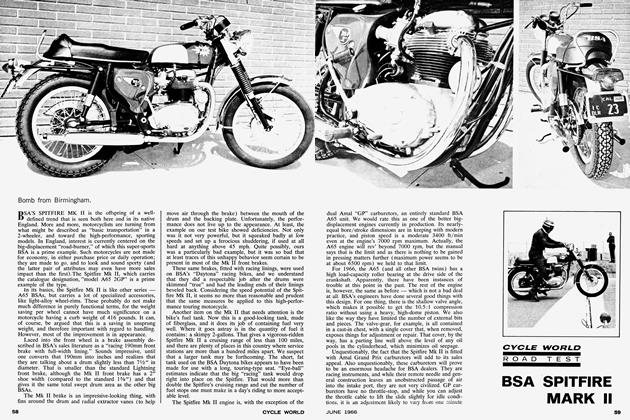

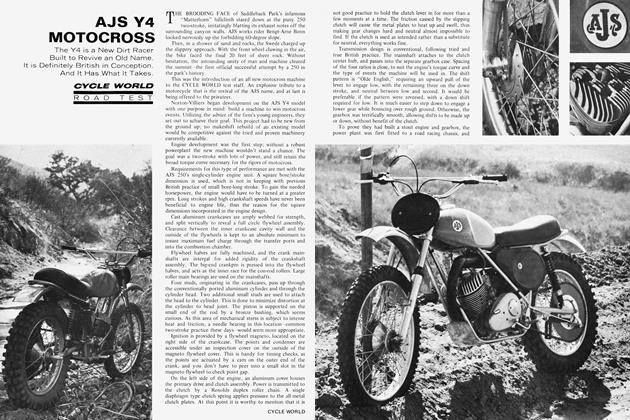

UNDOUBTEDLY, the likes of Joel Robert, Victor Arbekov and Roger de Coster would be impressively fast on a gaggle of Cushman Eagles. But, while such men of championship caliber thrill eager spectators with effortless jumps and slides, it would be foolish to think that they would use anything less than the absolute best equipment available. All romance aside, fortune figures little in the championship equation, The 250and 360-cc CZ motocross machines tested by CYCLE WORLD are the tools of champions; no gimmicks, as frilly as a yeoman’s cudgel, a motocross CZ is simply one of the best racing machines made.

The CZ engines have seen substantial revision since the last visit of these motorcycles to the pages of CYCLE WORLD (CW, June ’66, March '61). The aluminum iromsleeved cylinder sports five ports, each of generous dimensions and relatively mild timing. The piston pin bushing has been replaced by a caged needle bearing assembly, while the pistons are forged in West Germany by Kolbenschmidt. Each piston is surrounded by a pair of chrome plated rings. The connecting rod remains all but unchanged, except to accommodate the bearings on the small end. Nonetheless, it is a very strong unit, made of forged steel utilizing roller bearings in the big end.

The ball main bearings are shrunk into steel collars which are pressed into the crankcase halves. These collars were made of brass on previous units.

The quality of CZ construction is impeccable. Engine and transmission parts are measured during production and marked accordingly. Then, farther down the assembly line, only those parts marked with corresponding numbers are matched for a machine. The system is quite efficient and achieves remarkable quality control.

The clutch is all new. It is now mounted on the mainshaft rather than the crankshaft. This is beneficial in that the operating speed of the clutch is much less than when it was crankshaft-mounted. Consequently, clutch action is smoother and easier to control. On the other hand, the new arrangement transmits more torque to the clutch, as there is a ratio reduction through the primary gears. This issue is strictly academic, however, and matters not a whit because of the obvious strength in the new clutch. It no longer operates in an oil bath, but is a dry unit with three friction plates. The plates are made of alloyed steel and coated with a special type of porcelain. The assembly is very strong and capable of transmitting many times the torque it is subjected to.

The transmission is a piece of smoothness and precision. All the shafts rotate in ball bearings and the case-hardened gears turn in needle bearings. Shifting seemed no more difficult without the clutch than with it, a fact welcome in the heat of competition. This is because of the generously wide engagement dogs. Even though all the shafts and gears have been enlarged, there is not the slightest hesistancy to snap from gear to gear. The unique shifting mechanism deserves much of the credit for this. Just beneath the inspection plate atop the transmission, a sliding plate is mounted on bearings. This plate has two pathways in its surface that control movements of the shifting forks. Movement of the gear selector affects the position of the plate, and, consequently, the coggery. It is a positive system and not likely to develop slack with hard use.

Changing countershaft sprockets is done with little bother. The sprocket is out in the open on the bike’s right side. Also, the tool kits which accompany the bikes contain a couple of extra sprockets (and carburetor jets) so there will be little inconvenience for on-the-spot tuning. That inimitable CZ quality extends to every piece of the machines. The drive chain is no exception. It is manufactured by CZ and promises a trouble-free, long life because it has a brass bushing between each pin and roller. This arrangement ensures against chain stretch, long a dirt bike bane.

Both test machines were fitted with Barum Speedway tires, the favorite of many Class A J.A.P.s and ESOs. They differ from the regular knobbies in that the tread extends farther down the sides of the tire. Also, the side tread pattern has narrow serrations in each knob. These tires cling furiously to the dirt when heeled over and contribute much to the machines’ forgiving nature. On the other hand, the Barums appeared to wear fast, which is the price you have to pay.

The CZ frame is of the same configuration used in previous models. The main frame has a large diameter toptube and down tube, which connect with smaller diameter central loops. These, in turn, are heli-arced to still smaller diameter tubes which form the rear part of the frame. The unit is made of chrome-moly steel and should prove eminently durable and flex-free.

The 250 and 360 CZs are perhaps the smoothest riding of the world’s top motocrossers. The suspension is of conventional design but is well damped and behaves well. The rear wheel has about 3.5 in. of travel, which may not sound quite adequate to some, but it never bottomed throughout the test. The front fork has more than 6.5 in. of travel and offers just enough damping without being at all soft.

The seating position is very comfortable-which should make it popular with desert riders. One reason for this comfort is the rather low position of the rigid pegs. While this may cause some rider concern when navigating narrow ruts (for fear of smashing a foot), it does allow the rider to get more leg and knee onto the machine, hence, much more control. This is particularly evident when riding the CZ in a standing position, as the machine is quite sensitive to front-to-rear and side-toside weight variations. The tough, steel pegs do not fold, but this is preferable, as they protect the feet when the pegs scrape the walls of a rut, or a banking. There may be more than a casual reason why Joel Robert rides slightly pigeon-toed: to keep'his feet protected by the width of the pegs. The pegs may be adjusted up or down a few inches to fit the rider’s taste, a decidedly good feature that few other bikes boast.

During the test, most riders expressed preference for the 250-cc machine, indicating that it was somewhat easier to keep “on line.” The 360 produces positively brutish torque with a very wide power band, which makes it easy to ride in that respect. But only a very experienced hand can fully utilize what the bike offers. It out-accelerated every other dirt bike encountered. The 250 is geared lower than the 360, in addition to being 10 lb. lighter, and seemed generally more controllable.

The brakes on the 250 are excellent, front and rear, and the controls offer good “feedback” from the drums. The 360’s brakes, identical to the 250’s, did not deliver the same stopping power. While the rear brake worked well, there seemed to be a slight malfunction in the front unit. Perhaps the shoe wasn’t aligned properly, but the necessary mechanical assistance was not there.

Unsprung weight on the CZs has been minimized by using magnesium alloy hub and brake assemblies. The front brake shoes rub against a pressed-in iron liner. The steel liner of the rear brake is bolted into place, while the 62-tooth rear wheel sprocket is a flange integral with the liner. And, because the spokes are attached directly to the sprocket flange, they are shorter and more rigid, thus that much stronger.

The ignition system is based on a flywheel magneto and twin coils. Each coil fires a spark plug set into the 10.5:1 compression ratio head. A single set of breaker points triggers the whole process, which leads us to believe that the voltage passing across the breakers might be a bit much as the points begin to wear. In any event, the P.A.L. spark plugs always fired under all riding conditions. Factory sources on this coast indicated that those CZs participating in the Inter-Am races ran the entire series without a plug change—impressive testimony indeed. Another benefit of the ignition system is its ease of maintenance. Instead of being shrouded by the flywheel, the points and condensor are easily accessible because the mouth of the flywheel is turned outward. To clean and reset points between races is no longer a frantic and hurried operation interspersed with profane litanies.

A pleasant treat is in store for the prospective CZ motocross buyer. The machines come with a remarkable array of spare parts. Included in this are one piston, rings (standard and 0.010 oversize), chain, connecting rod, piston pin and bearings, brakes, cables, levers, seals, gaskets, points, coil, condensor, spokes and nipples, and all sorts of incidentals. It should be noted that the kit was compiled by CZ factory technicians from Los Angeles to Montreal, not by an ad agency or those similarly unqualified. These parts are also marked and matched to the specific machine, so there is no danger of mismatched clearances or doubtful replacements.

As these are championship quality dirt machines, only the rare CZ will not be ridden hard and continually thrashed. For this reason we suggest that the CZ buyer safety-wire or Loctite those nuts and screws dear to him and his mount.

The CZ motocrossers were a real pleasure to possess, even temporarily. They were returned to American Jawa with genuine reluctance. However, there may be an even more promising bright spot in the future, as one CW staffer had a portentous dream recently,..something about a 402-cc bananaframe ISDT mount. [O]

CZ 360 AND 250

MOTOCROSSERS

$1075