Clipboard

RACE WATCH

Four-stroke Grand Prix rules defined

The FIM-ruling body of international motorcycle racing-will for 2002 invite 990cc four-strokes of three cylinders or more to compete in its top Grand Prix roadracing class, joining existing 500cc two-strokes.

Including four-strokes provides a “green option” for the FIM and the manufacturers. Clean two-stroke technologies exist, but have not yet been applied to the engines in GP bikes.

The FIM has said all along that it would not choose a four-stroke displacement close to that of any existing class. This sensibly avoids obvious overlap with the threateningly successful World Superbike Championship, a four-stroke production-based series that pits 750cc four-cylinder engines against l000cc Twins.

Why set displacement at 990cc, when current 750/l000cc Superbikes are already so close to two-stroke 500 times at certain circuits? Except perhaps for Honda, no one will go fourstroke GP racing if it requires monster R&D just to get in. Above all, GP racing needs full grids and exciting racing to survive against World Superbike in the global TV advertising-dollar derby. FIM GP teams have nothing like the sponsorship base of Formula One, where team budgets go as high as $300 million annually. The biggest bike GP team budget is only 3 percent of that. This forced the FIM to make its GP four-strokes big enough to achieve competitive power cheaply.

European engine design consultancies have wide experience with F-l auto engines. Three cylinders sawed off a current 3-liter V-10 engine make roughly 225 horsepower, which is a good number compared with the 175205 bhp currently associated with 500cc two-strokes. This fund of knowledge could further shorten the R&D path to competitiveness-especially for makers such as MV Agusta, which has a relationship with the Ferrari F-l team.

Why require a minimum of three cylinders? In the first year or two of a new series, the most likely winner is not some new horsepower king, but a team with a machine that is already highly developed from another series. In this case, that means Ducati’s 996 Twin.

Should anyone want to blow the budget (Honda, do you hear the FIM calling your name?), engines with more cylinders and/or oval bores are permitted to compete at higher minimum weights. Bikes with six cylinders or more, for example, must weigh an elephantine 341 pounds.

Honda’s new “General Manager of Racing,” five-time 500cc World Champion Mick Doohan, said recently that the new plan will “add variety and attract more manufacturers to compete,” and “makes the sport more appealing for manufacturers and engineers.” Establishment costs would be offset by “long-term benefits.”

This may actually turn out to be true, the big reason being the large 990cc displacement. With it, even smaller companies such as Aprilia, Triumph or MV Agusta could quickly make more power than any existing tires can handle. One or two Japanese manufacturers might very well begin with quickie souped-up versions of their production 900cc engines, equipped with F-l-style cylinder heads. Even at a shuffling 14,000-rpm redline and breathing no better than some hot street 600s, this would give an instant 200 bhp from such a thinly disguised Superbike. And with all the trimmings like ultra-short stroke and pneumatic valves? That would give numbers like 17,000 rpm and 240 bhp. And for a Six? More than 19,000 revs and close to 300 bhp.

The 500 GP class is already horsepower-saturated-everyone has more power than the tires can handle. The real game isn’t horsepower. It is to shape power delivery and suspension action to painstakingly extend the limits of what the tires can do. Switching to heavier, double-the-displacement four-stroke power will completely change these details, requiring the usual intensive search for new setups. The basic concept will remain the same. What else is new?

Kevin Cameron

Foreign entanglements

The AMA Grand National Cross Country Championship has long been a pitched battle among all the “good old boys” of American off-road racing, a playground for series veterans such as Rodney Smith and Scott Summers. Not anymore. This year, both riders have suffered from nagging injuries and bad luck, dropping from the leaderboard in favor of a pair of wildcards from overseas, Australian Shane Watts and England’s Paul “Fast Eddy” Edmondson.

KTM rider Watts is a former 125cc enduro world champion and came to the U.S. last year in search of a new racing challenge and enough pocket money to keep him in beans and bacon. He quickly found it on the GNCC circuit. After easily winning the first two events last year, he also rapidly acquired a reputation for earthy frugality by re-using race tires and sleeping under the stars next to his borrowed box van! Two more wins and a second place came before he wrecked his knee in an Australian rally event. He recovered in time for the last two GNCC rounds and scored enough points to wear the number four on his KTM in 2000.

Edmondson, meanwhile, was eating dust and humble pie last year, obviously struggling on a Suzuki with which he just couldn’t connect. The pundits wrote off the former enduro world champ as washed up, but a switch to Kawasaki this year has put him right back on track. Ironically, this longstanding series of uniquely American racing looks slated to be under foreign control before much longer.

Watts currently leads the field in race wins, with three victories after five rounds and two other podium finishes. He has literally lunged to the front of the pack, showing an ability to win from any starting position and on almost any size KTM (125, 200, 250, whatever. “Keeps me from getting bored, mate!”). Edmondson has a win and a string of three second-place finishes; a good, consistent points bankroll so far only interrupted by a DNF in the first round after running out of fuel while leading.

Breaking up this duo, and America’s best hope so far for a domestic champ, is Team Suzuki’s Steve Hatch, a veteran GNCC racer as well as a past AMA national enduro champion and Six Days gold medalist. Hatch is a flamboyant rider, always capable of an impressive holeshot and equally as capable of an amazing crash while running at the front of the pack. But his strength and stamina-he trains the other six days of the week-have been paying off. A string of top-five finishes has set him second in points.

And what of the perennial champions? Summers is still trying to get his sea legs after suffering from a broken femur in ’99, not to mention knee surgery early this year. Smith has started well with two strong finishes (including a win at round two), but a torn leg muscle has him sidelined, and his quest for points looks bleak in the face of all this competition. Former champion Fred Andrews has led nearly every race, but freak injuries and breakdowns have kept him away from serious points accumulation.

The GNCC is without a doubt a major national series and an eastern U.S. tradition. But the flag at the top of the podium at the final round may well be that of Australia, flying for a champion who dreams of a swag (thin sleeping bag) and a slab (case of beer) and a ute (utility vehicle)-drivin’ sheila (girl next door with halt a slab in her) under the stars. Goodonya!

Paul Clipper

Ice racing: the indoor Cold War

For motorcycle enthusiasts in the U.S., perhaps the most obscure form of competition in their favorite sport is speedway ice racing. Back when most American race fans had their eyes pointed toward sunny Daytona Beach to witness their two-wheeled Rite of Spring earlier this year, the Ice Racing World Championship was being decided in the chilly climes of Assen, Holland.

Ice racing is one of the grandfathers of motorcycle racing, getting its start in Germany during the mid-’20s.

It gained in popularity in the northern part of the northern hemisphere (for obvious climatic reasons) through the following decades, then took a break during that World War II thing. Just about the time the Cold War got its start in the 1950s, the Russians, masters of many things ice, began a domination of the sport that has more or less continued to this day.

“Spike bike” racing has enjoyed continued popularity due in part to the fact that it is one of the most intense forms of motorcycle racing on the planet. If roadracer lean angles impress you, one look at an ice racer skimming his elbow around the oval track might just bring you into the Cold Fold.

This sport is not for the timid. In each heat, four riders compete for four laps, essentially riding with the throttle pinned down the straights and almost pinned in the corners, shooting chunks of ice out into the audience all the while. “I’ll take a mixed drink, not beer this time...”

And though plenty of ice makes its way outside the track, you can imagine how difficult it is to maintain visibility with one of these snow blowers doing its business in front of you. No wonder the riders work so hard on getting their starts down. They carefully adjust the clutch to slip just enough so the bike won’t flip over on a full-throttle, dumpthe-clutch race start, yet won’t slip later in the race.

When the starting tapes fly, riders fight the inevitable wheelies (the inchlong spikes in the tires do let the machines hook up rather well), then they slam over violently to near-horizontal for the first turn. In fact, there’s a machined ball of aluminum on the left handlebar end for those times when only fully flicked will do! Thank the spinning ice picks, with roughly 100 spikes in the 23-inch front tire and 170 in the 21-inch rear, depending on the hardness of the ice. As you can imagine, these “tires” are the main piece of technology that makes the ice-racing world go round-and lends a real gravity to outside passing maneuvers! All of this traction cuts deep grooves in the ice surface, which makes the racing even more unpredictable as the track deteriorates.

Like standard speedway bikes, the Czech-made Jawa ice racers have gone relatively unchanged through the years. All are powered by methanol-burning 500cc four-stroke Singles producing around 60 horsepower and working through a two-speed gearbox (first is used only for the start). Jawa makes just 10-15 complete bikes each year, but sells engines to those wishing to try their own hand at frame building. Oh, yes, and in the finest speedway tradition, there are no brakes.

Each year, a different country hosts the World Championship, with fans often chartering buses to the distant events and partying the whole way there. Motor racing fans are motor racing fans, no? This year’s championship final was held in front of a crowd of 10,000. The two-day event was won by a Russian named Kyril Drogalin, who added a second World Championship to his 1997 victory. His stiffest competition came from Austria’s Franz Zorn and fellow Russian Vladimir Fadeev, who was the 1999 champ. Zorn is considered the best non-Russian ice racer. Some 40 four-lap heats are run, riders collecting points in each that count toward the championship. Drogalin managed a tight overall win-just a one-point margin over Zorn, knowing in his last heat he only had to finish second. Which is exactly what he did-no reason to try an unnecessary outside pass!

Michael Burnham

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

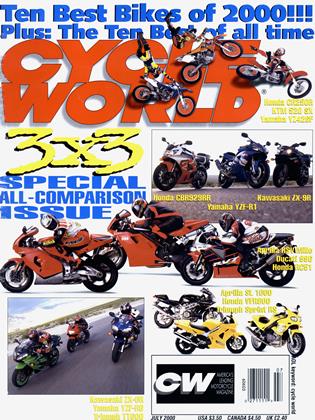

Up FrontThe Ten Rest, 2000

July 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Perfect Baja Bike

July 2000 By Peter Egan -

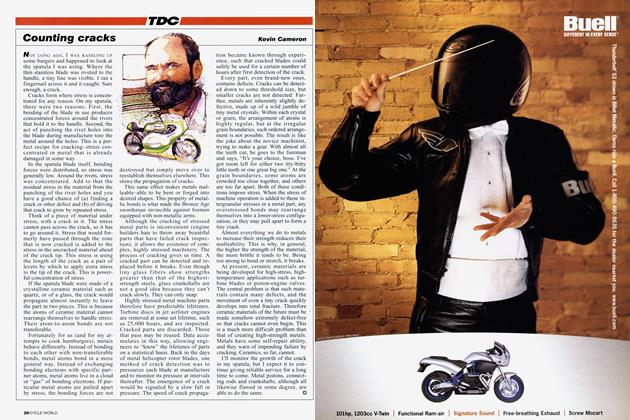

TDC

TDCCounting Cracks

July 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

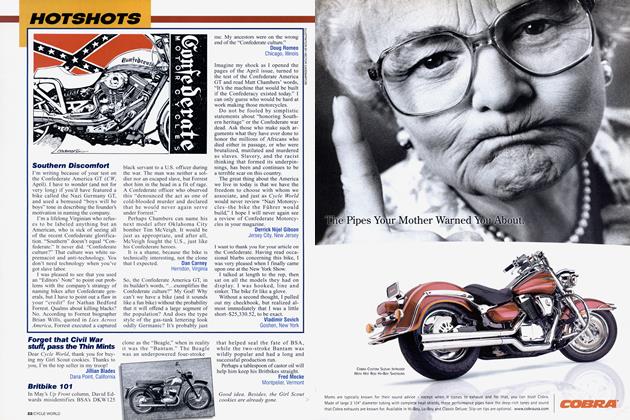

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

July 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupFriedel Münch Strikes Again

July 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupAprilia Buys Moto Guzzi

July 2000 By Bruno De Prato