THE 24 HOURS OF BRETAGNE

RACE WATCH

To the French, even a motocross can become a cause célèbre

DAVID EDWARDS

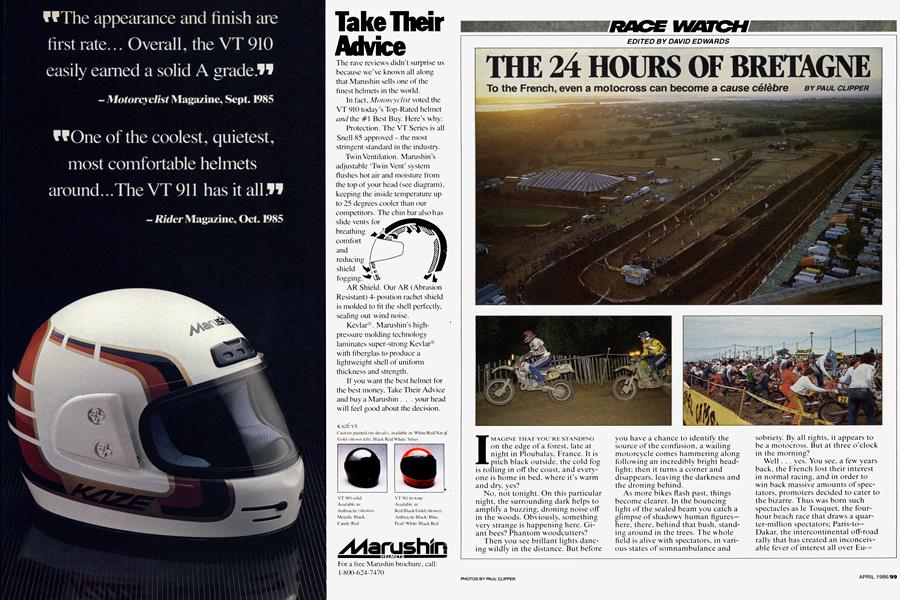

IMAGINE THAT YOU'RE STANDING on the edge of a forest, late at night in Ploubalay, France. It is pitch black outside, the cold fog is rolling in off the coast, and everyone is home in bed, where it's warm and dry, yes?

No, i~t tonight. On this particular night, the surrounding dark helps to amplify a buzzing. droning noise off in the woods. Obviously, something very strange is happening here. Gi ant bees? Phantom woodcutters? Then you see brillant lights danc

ing wildly in the distance. But before you have a chance to identify the source of the confusion, a wailing motorcycle comes hammering along following an incredibly bright head light: then it turns a corner and disappears. leaving the darkness and the droning behind.

As more bikes flash past, things become clearer. In the bouncing light of the sealed beam you catch a glimpse of shadowy human figureshere, there, behind that bush, stand ing around in the trees. The whole field is alive with spectators. in vari ous states of somnambulance and sobriety. By all rights. it appears to be a motocross. But at three o'clock in the morning?

Well . . . yes. You see, a few years back, the French lost their interest in normal racing. and in order to win back massive amounts of spec tators, promoters decided to cater to the bizarre. Thus was born such spectacles as le Touquet. the four hour beach race that draws a quar ter-million spectators; Paris-toDakar, the intercontinental off-road rally that has created an inconceiv able fever of interest all over Eu-> rope; and the 24 Hours of Bretagne. The 24 Hours is a motocross race

PAUL CLIPPER

run on an eight-kilometer course by teams of three riders per motorcycle. The event begins with a Le Mansstyle start at four o'clock on Sat urday afternoon, continues all Saturday night and Sunday morning, and finally finishes on Sunday after noon, to the great relief of partici pants and spectators alike. The race is divided up into four legs, three of which are six hours long, with the last leg lasting only an hour and a half. So actually, the 24 Hours of Bretagne is only a 19½-hour race; but afterwards, if you talk to any of the contestants, you get the distinct impression that they feel they've gotten their money's worth.

So much time in the saddle turns into a brutal chore very quickly, and the 24 Hours demands more than the average amount of machine preparation. The most critical prob lem is getting sufficient lighting for the night laps. and every team seems to have a different approach for turning darkness into navigable twi light. Dual lights are common, and

it is not unusual to find a triple quartz-halogen headlight setup bolted to quick-disconnect mounts. One team even rigged up an auto motive alternator driven from the output shaft to generate the nec essary juice. Then, after the lighting problem is solved, the rest of the motorcycle has to be bathed in

thread-locking compound to help it survive the hours of punishment.

Such a commitment of time and energy all but eliminates the casual (read "budget") competitor, and al most all of the teams are shopor factory-sponsored. The most reknowned teams entered this year were the Royal Moto/KTM factory team of Heinz Kinigadner, Kees van der Ven and Gerard Rond: the Gauloises/Yamaha team of Jacky Vimond, Pierrick LeBlanc and JeanPaul Mingels: the Kawasaki France team of Jean-Jacques Bruno, Phi lippe Branle and Olivier Perrin; and the Ecurie Honda team of Gilles Lalay, Jean Michel Baron and Chris tian Vimond.

Kinigadner was fresh from his sec ond World Championship and very popular with the crowd, but the local favorite was Frenchman Jacky Vimond. As luck would have it, both teams suffered misfortune after an early runaway-the KTM team through food poisoning, the Yamaha team through engine failures. Note worthy was the Yamaha team's val iant effort, pushing the dead motorcycle through an entire lap in order to enter the pits legally and make repairs. The first time, they were a big hit with the cheering crowd: but the second time the en gine soured, the team packed it in rather than take the long walk.

The racers look forward to the finish for obvious reasons-a chance to rest, finally. The spectators, how ever, may have the hardest job; properly watching this race means braving the pounding beat of a rau cous rock band, sampling the distractions of a carnival-like mid way. and drinking large quantities of the local brew. The activities reach a fevered pitch at about 3 a.m., and, as you might guess, so much fun is not without a few casualties. An early-morning walk around the cir cuit reveals a number of dismantled haybales, each one covering the ex hausted body of a spectator who didn't make it through the night.

There is no huge amount of

money to be made by winning this race, only fame and great admira tion. This year, the Kawasaki France team struggled to victory on a KX500 motocrosser, but to give a blow-by-blow account would be impossible. as well as misleading. Everyone who's ever been there will tell you that spectating at the 24 Hours of Bretagne has nothing to do with watching a race: it is an all night party with motorcycles thrown in. And to the French, it is exactly what racing is all about.

RACE WATCH CALENDAR

Championship Events

AMA/Camel Pro Series

AMA Supercross Series

AMA National Enduro Series

World Roadrace Series

World Endurance Roadrace Series

World MX Series

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialBack To Square One?

April 1986 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeThe Ultimate Vee

April 1986 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1986 -

Roundup

RoundupLatest Ninja Offspring

April 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupThe Black Queen

April 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

Features

FeaturesHigh In the Thin, Cold Air

April 1986 By Koji Hiroe