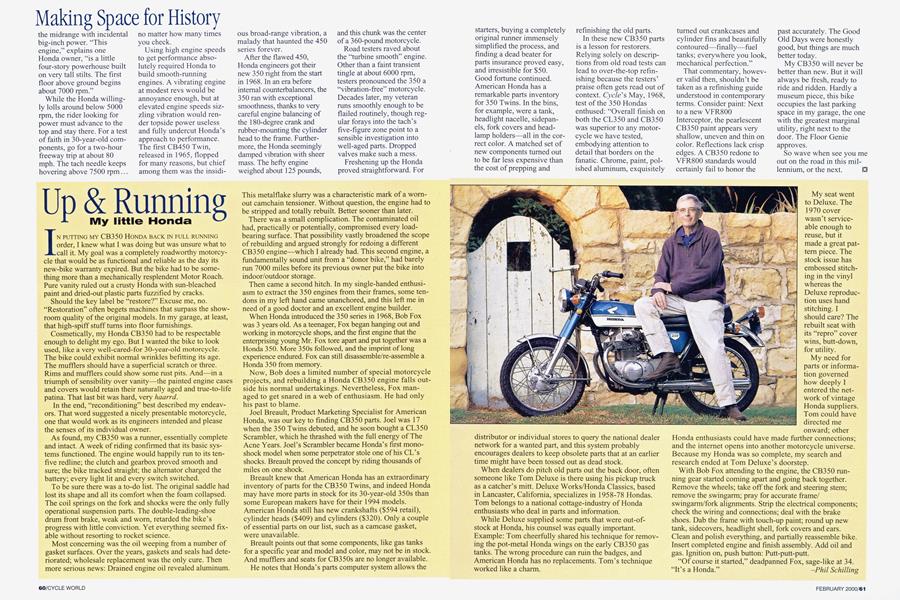

Up & Running

My little Honda

IN PUTTING MY CB350 HONDA BACK IN FULL RUNNING order, I knew what I was doing but was unsure what to call it. My goal was a completely roadworthy motorcycle that would be as functional and reliable as the day its new-bike warranty expired. But the bike had to be something more than a mechanically resplendent Motor Roach. Pure vanity ruled out a crusty Honda with sun-bleached paint and dried-out plastic parts fuzzified by cracks.

Should the key label be “restore?” Excuse me, no. “Restoration” often begets machines that surpass the showroom quality of the original models. In my garage, at least, that high-spiff stuff turns into floor furnishings.

Cosmetically, my Honda CB350 had to be respectable enough to delight my ego. But I wanted the bike to look used, like a very well-cared-for 30-year-old motorcycle.

The bike could exhibit normal wrinkles befitting its age.

The mufflers should have a superficial scratch or three. Rims and mufflers could show some rust pits. And—in a triumph of sensibility over vanity—the painted engine cases and covers would retain their naturally aged and true-to-life patina. That last bit was hard, very haarrd.

In the end, “reconditioning” best described my endeavors. That word suggested a nicely presentable motorcycle, one that would work as its engineers intended and please the senses of its individual owner.

As found, my CB350 was a runner, essentially complete and intact. A week of riding confirmed that its basic systems functioned. The engine would happily run to its tenfive redline; the clutch and gearbox proved smooth and sure; the bike tracked straight; the alternator charged the battery; every light lit and every switch switched.

To be sure there was a to-do list. The original saddle had lost its shape and all its comfort when the foam collapsed. The coil springs on the fork and shocks were the only fully operational suspension parts. The double-leading-shoe drum front brake, weak and worn, retarded the bike’s progress with little conviction. Yet everything seemed fixable without resorting to rocket science.

Most concerning was the oil weeping from a number of gasket surfaces. Over the years, gaskets and seals had deteriorated; wholesale replacement was the only cure. Then more serious news: Drained engine oil revealed aluminum. This metalflake slurry was a characteristic mark of a wornout camchain tensioner. Without question, the engine had to be stripped and totally rebuilt. Better sooner than later.

There was a small complication. The contaminated oil had, practically or potentially, compromised every loadbearing surface. That possibility vastly broadened the scope of rebuilding and argued strongly for redoing a different CB350 engine—which I already had. This second engine, a fundamentally sound unit from a “donor bike,” had barely run 7000 miles before its previous owner put the bike into indoor/outdoor storage.

Then came a second hitch. In my single-handed enthusiasm to extract the 350 engines from their frames, some tendons in my left hand came unanchored, and this left me in need of a good doctor and an excellent engine builder.

When Honda introduced the 350 series in 1968, Bob Fox was 3 years old. As a teenager, Fox began hanging out and working in motorcycle shops, and the first engine that the enterprising young Mr. Fox tore apart and put together was a Honda 350. More 350s followed, and the imprint of long experience endured. Fox can still disassemble/re-assemble a Honda 350 from memory.

Now, Bob does a limited number of special motorcycle projects, and rebuilding a Honda CB350 engine falls outside his normal undertakings. Nevertheless, Fox managed to get snared in a web of enthusiasm. He had only his past to blame.

Joel Breault, Product Marketing Specialist for American Honda, was our key to finding CB350 parts. Joel was 17 when the 350 Twins debuted, and he soon bought a CL350 Scrambler, which he thrashed with the full energy of The Acne Years. Joel’s Scrambler became Honda’s first monoshock model when some perpetrator stole one of his CL’s shocks. Breault proved the concept by riding thousands of miles on one shock.

Breault knew that American Honda has an extraordinary inventory of parts for the CB350 Twins, and indeed Honda may have more parts in stock for its 30-year-old 350s than some European makers have for their 1994 models. American Honda still has new crankshafts ($594 retail), cylinder heads ($409) and cylinders ($320). Only a couple of essential parts on our list, such as a carnease gasket, were unavailable.

Breault points out that some components, like gas tanks for a specific year and model and color, may not be in stock. And mufflers and seats for CB350s are no longer available.

He notes that Honda’s parts computer system allows the distributor or individual stores to query the national dealer network for a wanted part, and this system probably encourages dealers to keep obsolete parts that at an earlier time might have been tossed out as dead stock.

When dealers do pitch old parts out the back door, often someone like Tom Deluxe is there using his pickup truck as a catcher’s mitt. Deluxe Works/Honda Classics, based in Lancaster, California, specializes in 1958-78 Hondas. Tom belongs to a national cottage-industry of Honda enthusiasts who deal in parts and information.

While Deluxe supplied some parts that were out-ofstock at Honda, his counsel was equally important. Example: Tom cheerfully shared his technique for removing the pot-metal Honda wings on the early CB350 gas tanks. The wrong procedure can ruin the badges, and American Honda has no replacements. Tom’s technique worked like a charm.

My seat went to Deluxe. The 1970 cover wasn’t serviceable enough to reuse, but it made a great pattern piece. The stock issue has embossed stitching in the vinyl whereas the Deluxe reproduction uses hand stitching. I should care? The rebuilt seat with its “repro” cover wins, butt-down, for utility.

My need for parts or information governed how deeply I entered the network of vintage Honda suppliers. Tom could have directed me onward; other

Honda enthusiasts could have made further connections; and the internet opens into another motorcycle universe. Because my Honda was so complete, my search and research ended at Tom Deluxe’s doorstep.

With Bob Fox attending to the engine, the CB350 running gear started coming apart and going back together. Remove the wheels; take off the fork and steering stem; remove the swingarm; pray for accurate frame/ swingarm/fork alignments. Strip the electrical components; check the wiring and connections; deal with the brake shoes. Dab the frame with touch-up paint; round up new tank, sidecovers, headlight shell, fork covers and ears.

Clean and polish everything, and partially reassemble bike. Insert completed engine and finish assembly. Add oil and gas. Ignition on, push button: Putt-putt-putt.

“Of course it started,” deadpanned Fox, sage-like at 34. “It’s a Honda.” —Phil Schilling