Hot Rod Reunion

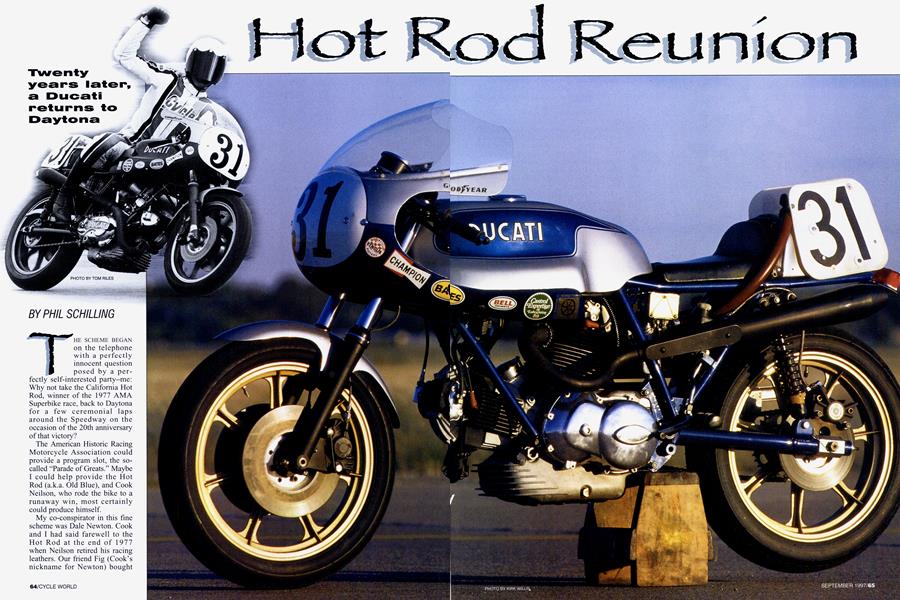

Twenty years later, a Ducati returns to Daytona

PHIL SCHILLING

THE SCHEME BEGAN on the telephone with a perfectly innocent question posed by a perfectly self-interested party-me: Why not take the California Hot Rod, winner of the 1977 AMA Superbike race, back to Daytona for a few ceremonial laps around the Speedway on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of that victory?

The American Historic Racing Motorcycle Association could provide a program slot, the socalled “Parade of Greats.” Maybe I could help provide the Hot Rod (a.k.a. Old Blue), and Cook Neilson, who rode the bike to a runaway win, most certainly could produce himself.

My co-conspirator in this fine scheme was Dale Newton. Cook and I had said farewell to the Hot Rod at the end of 1977 when Neilson retired his racing leathers. Our friend Fig (Cook’s nickname for Newton) bought the entire lot of Ducati racing hardware to augment his own very successful Superbike racing program with rider Paul Ritter.

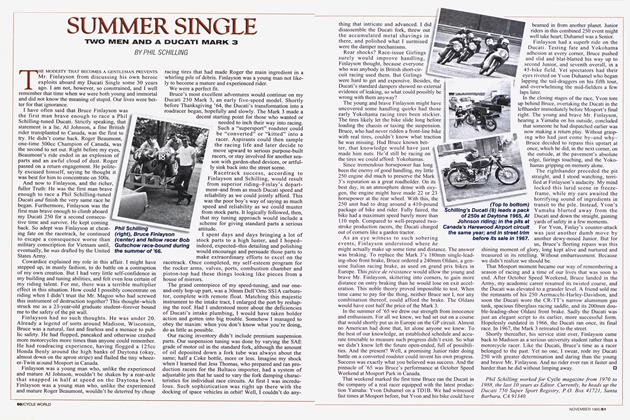

But then Dale did something very unusual. He kept the rolling chassis of the California Hot Rod intact and put its bodywork on the shelf. Years later, long after bevel-drive Ducati Twins had become history, Fig reunited the parts that made up the 1977 Daytona engine and reassembled the bike. Far from being “restored,” the California Hot Rod-thanks to Dale-had just been waiting to get back together again.

The last time I spoke to Newton, he phoned me up late in 1995. We talked about doing the Hot Rod Reunion and reminisced about dozens of other things. In an incidental way, he mentioned that he had some nagging medical problems which he and his doctors had pretty well licked, and he was feeling much better.

Just a short time later, death sideswiped Dale.

Often, I remember friends by the words special to them. “Keen” was a Dale Newton signature word. Keen means finely sharpened, intense, piercing, enthusiastic or ardent, great or wonderful. Dale was all those things, and every time I hear that word, he flashes into my mind’s eye. Dale Newton was a keen guy keen on doing keen projects. One such undertaking was the Hot Rod Reunion.

With his father gone, Dale’s oldest son, Glen, stepped in and made the reunion his project. As Daytona 1997 approached, Glen focused on readying the Hot Rod, which stood completed as Dale had left it. Add gas, oil and battery, and a push. The bike boomed into motion. Small oil leaks appeared, and the ignition wiring needed sorting. Nothing serious, as Glen understood, but the bike had to be perfect.

There are risks in revisiting. Reunions carry the possibility of dimming the majesty of the original rather than burnishing it. In the Daytona program, historic racebikes get turned out to run three laps within a tight time-slot. No practice or jetting sessions; just do it. A recalcitrant bike can spend its entire allotted time on the grid refusing to start. Or badly prepared bikes may fire up only to stagger around the

Daytona race course, marking time with a barely connected series of sputters. Worse yet, should the bike unhorse the rider, or the rider unhorse himself, the anniversary ride might be the ruin of both bike and rider.

Shod with its ancient, age-hardened Goodyears, the Hot Rod would be treacherous at speed. When fresh from the mold, these racing slicks were absolutely magic on the Ducati. The California Hot Rod’s great “unfair advantage” was its capacity to fully exploit the grip of Goodyear racing slicks; mounted on lesser bikes, slicks caused handling convulsions.

Even at parade speeds, Neilson needed fresh slicks because he would use the tires, but Goodyear had stopped making motorcycle roadracing tires years ago. And Dunlop’s inventory list in the United States didn’t include racing rubber for the Ducati’s old-fashioned 18-inch wheels. At Dunlop, Jim Allen’s interest and intervention made all the difference. He sourced some patterned slicks (used in a race series in Britain) in the correct sizes, and got the tires delivered with time to spare. Without Allen, the pit wall would be as close to the track as the California Hot Rod dare go.

Daytona International Speedway, 1997: A score of years had passed since last I heard the California Hot Rod come to life.

Pushing from behind, just as the clutch drops and valves and pistons begin to beat, you catch a hard metallic sound, hollow and empty, clacking deep down in the megaphones. Then tiny, seemingly distant explosions suddenly jump into a thunderous bark that fills all immediate space. Tremendous compression hardens and sharpens the sound waves. At 1000 rpm, the engine settles into a crisp, rangy cadence. I could hear enough to know that the essential part of Old Blue remained untouched by the years. It was the same, and ready.

Neilson and the Ducati disappeared from the starting grid and swung onto the course. Accelerating away, the Hot Twenty years later, thank you and trust me, it was all just fine again. Jetting, spot-on. Gearing, the 150-mph combination. Tires, nice and sticky. Engine, 8300 rpm or more, no kidding.

Rod’s exhaust-boom seemed to collapse 20 years into a single long moment. What year is this, I thought, 1977 or 1997? For a fleeting few seconds, now converged with then:

I am standing in the dirt in the motocross construction area, between the racetrack and the starting grid, just a bit below the start/finish line. The race leaders appear in the distance, howling/bellowing toward the finish line at the end of the first lap. Cook trails Wes Cooley, who has the Yosh i mura Ka was aki flying.

I’m in dread. Is the Ducati fast enough? Did we do enough homework? Did we do it well enough? Will this thing let Neilson down? Thanks to my Puritan/Midwestern background, Tm our official pessimist and worrier; the guy who ’s afraid that if somehow, somewhere, someone is hav-

ing a good time, everything will turn to junk. Neilson and I make a balanced team because he gets out of bed every morning wondering what really terrific thing will happen today-“ Schiller, trust me, everything will be just fine! ’’

But Neilson is also one of the most ferocious competitors I’ve ever seen. He loves to excel and hates to lose. He's tried harder to get up front than anyone could imagine. He ’s my best friend, and I want to see him do what he so richly deserves: to win at Daytona.

Neilson ’s mind, I imagine, is completely uncluttered by such angst. He ’s way too busy. On lap two he closes up on Cooley and passes him in Turn 4. Then Cook and the California Hot Rod begin to stretch it out, stacking one second methodically atop another as the laps roll by. Soon Neilson has Old Blue thundering along in solitary splendor. Across the start/finish line, the Ducati gives off a terrifying blast of sound energy.

For Cook the checkered flag is just 12 miles away. I'm rooted on the dirt heap, stuck fast in anxiety. Cook ’s flawless riding has produced a commanding lead; he ’s 8 minutes and change from victory. But what if the bike breaks? Does worrying prevent potential failures from actually occurring? Am I really worried, or am I just afraid not to worry?

Standing nearby, Reno Leoni, the Ducati importer ’s technical maven and a first-class tuner, senses my anguish and offers assurance. “You can quit worrying now, Phil. It’s gonna last, he’s gonna win. ’’ Reno is right.

Cook gave the Hot Rod a damn good run. Why, someone

asked him after it was over, did you push the precious old relic that hard? The reply was classic Neilson: “I wanted to run Old Blue hard enough so that Schiller would be sure to hear it.” Thanks, Cook, I heard it loud and clear. I know Dale did, too. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

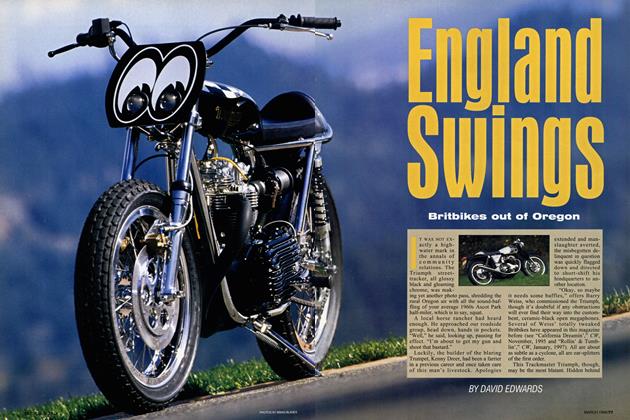

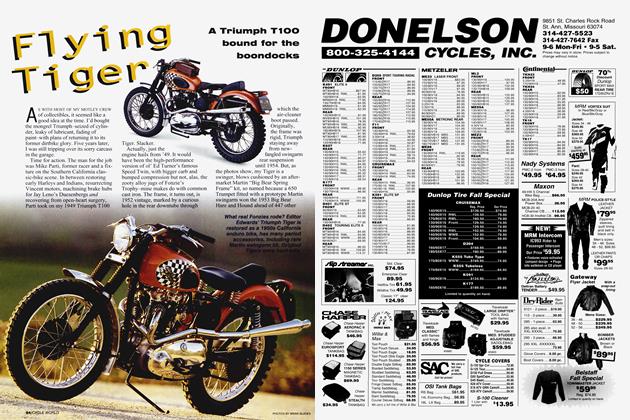

September 1997 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

September 1997 By Peter Egan -

Columns

ColumnsTdc

September 1997 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1997 -

Roundup

RoundupAt Last! Bimota's Two-Stroke Hits the Street

September 1997 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupSpied! New Yamaha Superbike

September 1997