Making Space for History

PHIL SCHILLING

DEPENDING ON YOUR point of view, my garage is either too small or contains too many motorcycles. The garage could be magnificently expanded into the rose garden, but the Goddess of the Garden and Protectress of All Plants on that Hallowed Ground resolutely dictates the status quo.

Fewer motorcycles would create more room, but beneath my garage floor lies some powerful magnetic force that makes all motorcycles permanent residents and occasionally attracts newcomers. So it’s a stand-off between the Floor Genie and the Garden Goddess.

In this counterpoise my motorcycles get packed in tighter, more intricate ways. A while ago, this high compression opened a final parking space, next to the door, for one last machine: a compact, versatile, universal roadster at home in town and on the highway, and preferably old enough to vote.

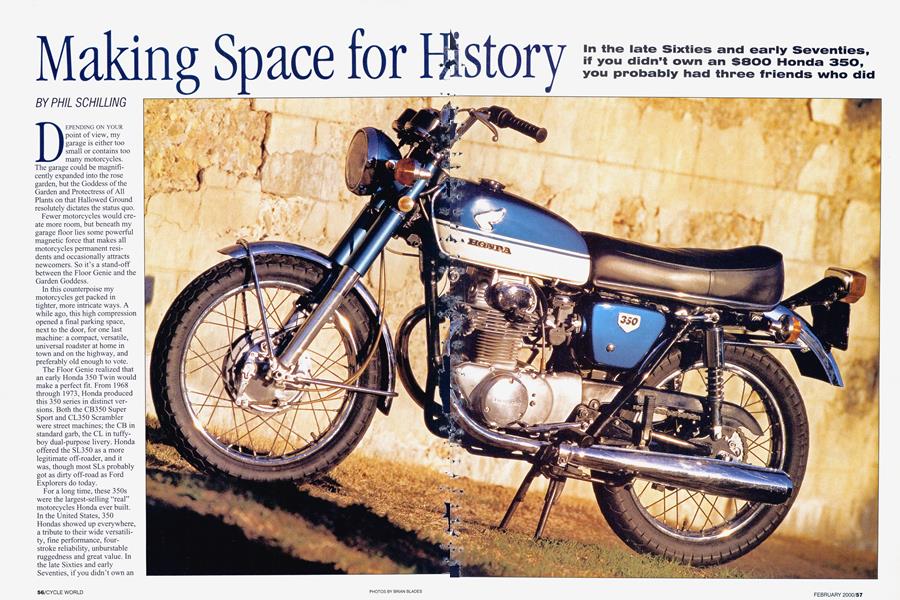

The Floor Genie realized that an early Honda 350 Twin would make a perfect fit. From 1968 through 1973, Honda produced this 350 series in distinct versions. Both the CB350 Super Sport and CL350 Scrambler were street machines; the CB in standard garb, the CL in tuffyboy dual-purpose livery. Honda offered the SL350 as a more legitimate off-roader, and it was, though most SLs probably got as dirty off-road as Ford Explorers do today.

For a long time, these 350s were the largest-selling “real” motorcycles Honda ever built.

In the United States, 350 Hondas showed up everywhere, a tribute to their wide versatility, fine performance, fourstroke reliability, unburstable ruggedness and great value. In the late Sixties and early Seventies, if you didn’t own an $800 Honda 350, you probably had three friends who did. Everyone, it seemed, had ridden one. For a long time, the 350 Honda was the most common denominator of the American streetbike experience.

History

In the late Sixties and early Seventies, if you didn’t own an $800 Honda 350, you probably had three friends who did

The significance of the wildly popular 350s bears explanation. This Honda achievement validated an idea that had previously been open to debate; namely, that there actually was a gigantic market for real motorcycles in the United States. The earlier and huge success of Honda’s nifty 50s scarcely demonstrated anything

about motorcycle prospects. The 350s’ predecessors, the 305 Super Hawk and 305 Scrambler, had sold in large enough numbers to suggest the truth of the proposition. Then the 350 series indisputably verified that there was a great universe of American enthusiasts who would buy real motorcycles—modem ones—in staggering numbers. It took

the right products at the right time in the right numbers to prove the point.

For all its importance, finding a nice Honda 350 now is an exercise in patience. In case you think Honda 350s must reside in junkyards where they occupy sprawling subdivisions of space, think again. Salvage yards are businesses; as a mle, they only stockpile parts and vehicles that sell. Honda 350 parts, so say the experts, don’t move. Observed one operator: “Honda 350 Twins are something less than junk.”

That insight focused my plans.

My objective became an original, complete, stock 350 that was a runner. A live example, unfortunately, would scarcely assure years of safe and trouble-free service. Consequently, my plan included the contingency of reconditioning the bike, from the crankshaft up and out, if required. When finished with the redo, I wanted to be done, and in possession of a totally fresh, functional and reliable vehicle.

My aesthetic sense sharpened my mental picture. The right Honda had to be a CB350 Super Sport from the 1968-70 model years. The gas tank really distinguished these years. To my eye, the tank possessed a simple, taut, elegant shape. In the 1968 and 1969 model years, this faintly British-looking tank carried rubber knee pads on its flanks; the 1970 tank, sans pads, looked sleeker.

Then was the silly matter of seams. The 1968-70 tanks had centerline seams on top, a production/design feature associated with early Hondas. Perversely, I liked the external seams in part because journalists made “seamless perfection” such a tiresome cliché about Hondas in the Seventies and Eighties. Starting in 1971, Honda fitted the CB350 with a bulbous melon of a tank that gave the Super Sport a ponderous appearance. And yes, the new tank had a seamless top.

The Honda 350 indisputably verified that there was a great universe of American enthusiasts who would buy real motorcycles— modern ones— in staggering numbers.

Picky people generally take a hot-pursuit approach to find exactly what they want. They comb ads, work the phones, hunt through dealers’ boneyards, network with friends and always follow the scent. For me, sustained flatout searching invites mental exhaustion which, in turn, causes me to buy the wrong thing. Therefore, before frazzling, I default into an alternate mode, the hammock pursuit. In this laid-back state, earnest daydreams reach out trying to attract the desired object. This phase can snooze to a stop, and that’s the signal to cycle back into hot pursuit.

My Honda 350 search ended as I was sequencing through the hammock phase for about the third time. A friend tipped me off. The bike was so close I could walk over and see it. And where would be the last place I’d check for a complete, original and running 1970 CB350 Honda Super Sport? Would you guess on the showroom floor of the local Honda dealer in the used-bike section? I jumped straight out of my hammock. And to the Honda store. For a test ride.

On the road, everything worked, 30 years after the 11/69 build-date stamped on the frame. Okay, everything didn’t work perfectly. The mufflers’ rust-eaten innards released exhaust music they once suppressed; the soft mellow wail of 1970 had become a flat, brash, rakish howl of 1999. And while the bike didn’t feel loose, it lacked the tight-togethemess of new—it was as if half the fasteners had backed out an eighth-turn. On-and-off use across 30 years and maybe 20,000 miles had flattened out the suspension damping, left the brakes indifferent and reduced the saddle stuffing to dust. Fine. The bike was complete and original and running. A little rehabilitation could fix everything. The 350 Honda would be my everyday runner, and my life richer for it.

Ca-ching, ca-ching. Done deal.

In the late Sixties, no one would have called the CB350 Super Sport an elemental machine.

Motorcycles that had electric starters and neutral lights automatically qualified as refined and sophisticated. The 350 was a fullscale motorcycle with modest displacement and real performance. By current standards, however, this Honda qualifies as smallscale bike, albeit a heavy one, with modest performance and little displacement.

Thus, in today’s context the CB350 is a simple, basic, old “standard” motorcycle. The bike positions its rider almost bolt-upright, unprotected from the elements. Engine layout fits nicely with plain air-cooling. Parallel cylinders poke the exhausts out front into the air stream and tuck the carburetors away behind the cylinder head. Placed behind a compact 3.2-gallon tank, the saddle—measuring 24 inches long and 10 inches wide—is the largest seat practical for a 52-inchwheelbase bike. Its standard layout allows the CB to be a little something of everything: 'round-town bopper, once-in-a-while tourer, occasional sportbike, solo or two-up.

Honda advertising tried to make the 350 a bit larger than life. The single-overhead-cam engine displaced only 324 cubic centimeters. Honda claimed 36 horsepower at 10,500 rpm and 15.5 footpounds at the 9500-rpm torque peak, and these sums, according to Honda, translated into a scintillating 13.8-second quartermile time.

Hard performance figures belied those lofty assertions. In a 1970 comparison test, Cycle magazine notched a 15.16-second/85.3 8-mph quarter-mile figure. In truth, the five-speed Honda probably made about 25 horsepower at the rear wheel, and maximum torque amounted to 11 or 12 foot-pounds. Those outputs, together with weight and quarter-mile numbers, roughly approximate those of Honda’s VTR 250 Twin built about 20 years later.

For a test of faith in 30-year-old components. two-hour freeway trip at about

But 25 horsepower can entertain.

The 64.0 x 50.6mm engine just loves to spin. This Sixties-style Honda four-stroke, feeding 162cc cylinders through 28mm carburetors and single intake valves, gathers its power at the top—where horsepower and torque peaks nearly coincide. Of course, the little Twin lacks the displacement to backfill the midrange with incidental big-inch power. “This engine,” explains one Honda owner, “is a little four-story powerhouse built on very tall stilts. The first floor above ground begins about 7000 rpm.”

While the Honda willingly lolls around below 5000 rpm, the rider looking for power must advance to the top and stay there. For a test of faith in 30-year-old components, go for a two-hour freeway trip at about 80 mph. The tach needle keeps hovering above 7500 rpm... no matter how many times you check.

Using high engine speeds to get performance absolutely required Honda to build smooth-running engines. A vibrating engine at modest revs would be annoyance enough, but at elevated engine speeds sizzling vibration would render topside power useless and fully undercut Honda’s approach to performance. The first CB450 Twin, released in 1965, flopped for many reasons, but chief among them was the insidious broad-range vibration, a malady that haunted the 450 series forever.

After the flawed 450, Honda engineers got their new 350 right from the start in 1968. In an era before internal counterbalancers, the 350 ran with exceptional smoothness, thanks to very careful engine balancing of the 180-degree crank and rubber-mounting the cylinder head to the frame. Furthermore, the Honda seemingly damped vibration with sheer mass. The hefty engine weighed about 125 pounds, and this chunk was the center of a 360-pound motorcycle.

Road testers raved about the “turbine smooth” engine. Other than a faint transient tingle at about 6000 rpm, testers pronounced the 350 a “vibration-free” motorcycle. Decades later, my veteran runs smoothly enough to be flailed routinely, though regular forays into the tach’s five-figure zone point to a sensible investigation into well-aged parts. Dropped valves make such a mess.

Freshening up the Honda proved straightforward. For starters, buying a completely original runner immensely simplified the process, and finding a dead beater for parts insurance proved easy, and irresistible for $50.

Good fortune continued. American Honda has a remarkable parts inventory for 350 Twins. In the bins, for example, were a tank, headlight nacelle, sidepanels, fork covers and headlamp holders—all in the correct color. A matched set of new components turned out to be far less expensive than the cost of prepping and refinishing the old parts.

In these new CB350 parts is a lesson for restorers. Relying solely on descriptions from old road tests can lead to over-the-top refinishing because the testers’ praise often gets read out of context. Cycle's May, 1968, test of the 350 Hondas enthused: “Overall finish on both the CL350 and CB350 was superior to any motorcycle we have tested, embodying attention to detail that borders on the fanatic. Chrome, paint, polished aluminum, exquisitely turned out crankcases and cylinder fins and beautifully contoured—finally—fuel tanks; everywhere you look, mechanical perfection.”

That commentary, however valid then, shouldn’t be taken as a refinishing guide understood in contemporary terms. Consider paint: Next to a new VFR800 Interceptor, the pearlescent CB350 paint appears very shallow, uneven and thin on color. Reflections lack crisp edges. A CB350 redone to VFR800 standards would certainly fail to honor the past accurately. The Good Old Days were honestly good, but things are much better today.

My CB350 will never be better than new. But it will always be fresh, ready to ride and ridden. Hardly a museum piece, this bike occupies the last parking space in my garage, the one with the greatest marginal utility, right next to the door. The Floor Genie approves.

So wave when see you me out on the road in this millennium, or the next.