CYCLE WORLD TEST

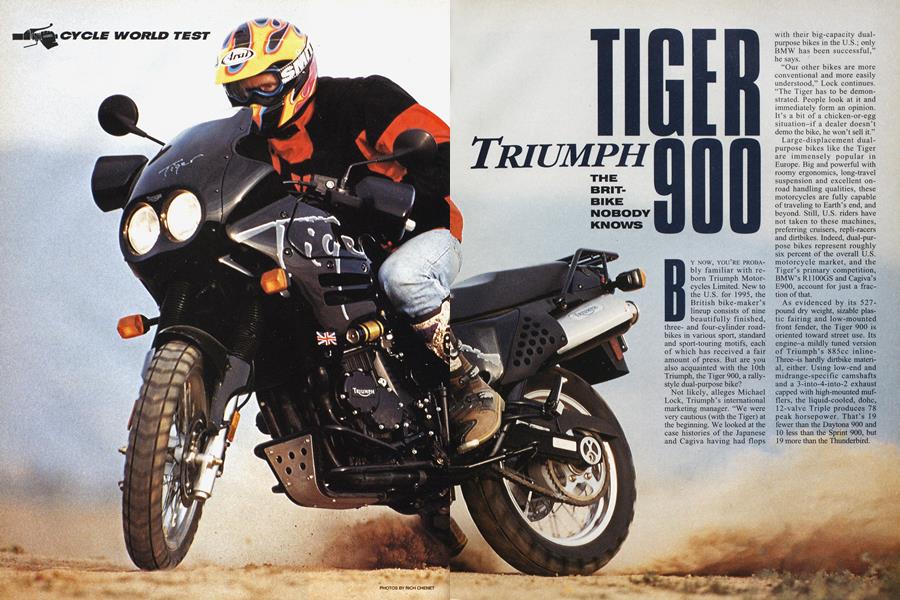

TRIUMPH TIGER 900

THE BRIT-BIKE NOBODY KNOWS

BY NOW, YOU'RE PROBAbly familiar with reborn Triumph Motorcycles Limited. New to the U.S. for 1995, the British bike-maker's lineup consists of nine beautifully finished, threeand four-cylinder road-bikes in various sport, standard and sport-touring motifs, each of which has received a fair amount of press. But are you also acquainted with the 10th Triumph, the Tiger 900, a rally-style dual-purpose bike?

Not likely, alleges Michael Lock, Triumph’s international marketing manager. “We were very cautious (with the Tiger) at the beginning. We looked at the case histories of the Japanese and Cagiva having had flops with their big-capacity dualpurpose bikes in the U.S.; only BMW has been successful,” he says.

“Our other bikes are more conventional and more easily understood,” Lock continues. “The Tiger has to be demonstrated. People look at it and immediately form an opinion. It's a bit of a chicken-or-egg situation-if a dealer doesn’t demo the bike, he won’t sell it.”

Large-displacement dualpurpose bikes like the Tiger are immensely popular in Europe. Big and powerful with roomy ergonomics, long-travel suspension and excellent onroad handling qualities, these motorcycles are fully capable of traveling to Earth’s end, and beyond. Still, U.S. riders have not taken to these machines, preferring cruisers, repli-racers and dirtbikes. Indeed, dual-purpose bikes represent roughly six percent of the overall U.S. motorcycle market, and the Tiger’s primary competition, BMW’s RI 100GS and Cagiva’s E900, account for just a fraction of that.

As evidenced by its 527pound dry weight, sizable plastic fairing and low-mounted front fender, the Tiger 900 is oriented toward street use. Its engine-a mildly tuned version of Triumph’s 885cc inlineThree-is hardly dirtbike material, either. Using low-end and midrange-specific camshafts and a 3-into-4-into-2 exhaust capped with high-mounted mufflers, the liquid-cooled, dohc, 12-valve Triple produces 78 peak horsepower. That’s 19 fewer than the Daytona 900 and 10 less than the Sprint 900, but 19 more than the Thunderbird.

Numbers can be deceiving, though, as is the case here. The engine makes its peak torque, almost 56 foot-pounds, at 6000 rpm. But nearly 90 percent of that peak is available way down at 3000 rpm, and between 3000 and 8000 rpm (redline is 8750 rpm), torque doesn’t vary by more than 9 percent. This translates into a very user-friendly power curve. Want further proof? Check out the dynamometer results: From just below 2000 rpm all the way to redline, power is smooth and seamless, with no perceptible spikes or dips.

There is one anomaly here, at least as the Tiger relates to other modem Triumphs. At lower rpm, the engine-and the view reflected in the circular, bar-mounted mirrors-is smooth as glass; but starting at about 4500 rpm, which translates into road speeds of roughly 65 mph in top gear, the Tiger begins to tingle through the handlebar, in spite of its rubber mounting and in spite of the engine’s counterbalancer. As rpm increases, so does the vibration; extended periods above 75 mph numb Fingertips. This is unusual because other Triumph Triples are generally very smooth. We suspect that the combination of the camshaft change, the tubular-steel handlebar (as opposed to the solid castings found on the other models) as well as the rubber mounting, are the likely culprits. We’ve no complaints about the multiplate wet clutch or the six-speed transmission. As with other modem Triumph gearboxes, shifts are sure and precise.

By design, the engine serves as a member of the chassis. It is solidly mounted to a large tubular-steel spine, which curves from the braced steering head over the engine to the swingarm-pickup points. Kayaba suspension components grace both ends of the bike, a non-adjustable conventional fork up front and a fully adjustable shock out back. With more than 9 inches of travel on tap, the 43mm fork soaks up all but the harshest roadway imperfections but is Firm and responsive enough to deliver sporting backroad performance. Dive under braking is considerable, but bottoming is not a problem.

Mated to the aluminum box-section swingarm, the centrally mounted shock offers an equally supple ride via nearly 8 inches of travel. Compression and rebound damping are readily altered with a flat-blade screwdriver, but spring preload changes require a spanner wrench, or a more primitive hammer-and-punch combination, neither of which are included in the underseat factory tool kit. Why Triumph didn’t use a more easily changed ramped preload collar or the underseat hydraulic adjuster found on other models is a mystery.

Front brakes consist of Fixed, 10.9-inch discs gripped by two-piston calipers. These extend substantial stopping power but are mushy and lack sensitivity. A two-Fingered pull, for example, brings the non-adjustable lever to your knuckles, and only a monster four-digit effort will lift the rear wheel off the pavement. Additional bleeding or steelbraided lines may provide a Fix. A two-piston caliper and 10-inch rotor are fitted at the rear. This combination, too, is spongy with excessive pedal travel.

Like the throwback Thunderbird, the Tiger rolls on spoked alloy wheels, in this case a 2.5 x 19-inch front and a 3.0 x 17-inch rear. Tires are provided by Michelin in the form of specially developed T66X dual-purpose radiais. More like hand-grooved roadracing slicks than motocrossstyle knobbies, they offer superb grip on the street, making it easy to fully explore the Tiger’s terrific ground clearance; even at white-knuckled cornering speeds, only the bike’s sidestand touches down.

A spirited outing on the Tiger is like an afternoon at your favorite amusement park, minus the long lines. On a twisty road with a capable rider aboard, the Tiger will cleave to the rear wheel of all but the best-ridden repli-racers. Unlike those narrowly focused machines, though, no frenzied hangoff antics are necessary. Predictable and sure-footed, the bike flicks into comers easily, and once there, remains nicely neutral. Handling eventually starts to evaporate, but only beyond supra-legal speeds.

Off-road capabilities, on the other hand, are extremely limited. Gravel access roads and well-travelled jeep trails won’t present any real concerns as long as the pace is kept at a sensible level, but anything more challenging could lead to painful, and costly, consequences.

Around town, the Tiger is extremely comfortable, its wide, MX-style handlebar, thickly padded seat and slightly rearset, rubber-covered footpegs providing a near-perfect riding position. Wind protection is pretty good, although buffeting at faceshield level bothered at least one tester. The 33.5-inch seat height might pose problems for shorter and/or less experienced riders, especially at stoplights and intersections. Still, the Tiger is less physically intimidating than the hulking RI 100GS, even if it only weighs three pounds less than that machine.

On long street rides, the stepped seat would benefit from denser foam. As is, pilot and passenger begin to squirm after less than two hours of saddle time; fortunately, there’s plenty of room to move around and change position. Also, the aluminum master-cylinder guard located just aft of the rightside swingarm pivot contacts the pilot’s boot-not a real problem, just a minor annoyance for some riders.

The standard-issue, tube-steel luggage rack doesn’t intrude on passenger quarters and will accommodate a tailpack or duffle. That’s good, because the humpback shape of the 6.5-gallon plastic gas tank won’t allow a tankbag, magnetic or otherwise. Locking, hard luggage is offered as an option. For $624, you get a pair of 36-liter saddlebags. An extra $116 scores a matching top trunk, or you can purchase the trunk separately for $274. A jumbo-sized, 50-liter trunk retails for $319. All prices include mounting hardware.

To the hard-core sportbike enthusiast bent on eye-watering top speed and uncompromised handling, features like optional hard luggage, a practical riding position and cushy suspension probably don’t hold much appeal. But the Tiger is more than just a practical, user-friendly commuter. It’s a two-up tourer, a light-duty dirtbike and a Sunday-morning backroad blitzer, a go-anywhere streetbike without limits. Put simply, it resists neat classification.

Too bad Triumph imported only 125 of them.

TRIUMPH TIGER 900

$9895

EDITORS' NOTES

THE TIGER 900 is JUST ABOUT THE biggest surprise to roll through our offices this year. I thought there was no way Triumph could touch BMW or Ducati in the jumbo-size rally-replica market. I was wrong.

The Tiger really is just a streetbike wearing a rally suit, and it may lack a bit of idle-level torque, but everywhere else it runs with the GS and the E900. Based on feel and handling, I’d pick the Triumph first. Yeah, I know the Tiger is about as heavy as the BMW, but once rolling it feels 50 pounds lighter.

But the best part may be the exhaust’s bark. If I got my hands on one of these, I’d get some noisy pipes, enter the Baja 1000, catch riders and throw revs at them. Man, they’d jump out of the way so quick-the Tiger 900 roars just like Ivan Stewart’s desert truck. And imagine the looks I’d get when I blasted past on a “streetbike,” horn beeping and tumsignals flashing. -Jimmy Lewis, Oj)-Road Editor

MOTORCYCLING HAS ALWAYS PRESENTED an opportunity to separate myself, both literally and figuratively, from the automotive masses. Triumph’s rally-style Tiger 900 pushes this thinking one step further, reinforcing the real reason as to why I spend so much time on two wheels: It’s fun, pure and simple.

For me> the bike’s upright riding position is a major plus, so is the optional hard luggage. But if first-class accommodations and cubic storage were my foremost prerequisites, I’d be salivating over luxury-class sport-utility vehicles, not motorcycles.

Powerful, wonderfully responsive and captivating in its appearance, this smooth-shifting neo-Triumph is fast enough to take on any real-world, street-riding assignment. And its handling will shame even well-ridden repli-racers. As a whole, it’s comfortable, practical, stylish and versatile. What more could any two-wheeled enthusiast ask for?

-Matthew Miles, Managing Editor

WHAT WE HAVE HERE IS THE SUPERBIKE of big-bore rally-replicas. Truth to tell, I think BMW’s RI 100GS probably is a better all-around bike, especially with its idiot-proof ABS and Tele-gizmo front end. But the Tiger sounds nastier, is more fun to romp though the gears and pulls galaxy-class wheelies.

A question, though: Since no sane man would attempt serious off-roading on one of these behemoths (disregard this test’s lead photo of Doug Toland backing the Tiger through a comer-he lost his sanity years ago), why not forgo all this camshaft switching and tuning-for-midrange rigamarole and give the Tiger the full-house Daytona 900 motor? Sure 78 rearwheel horsepower is nice, but the Daytona’s 97 would be more nicer-and it makes 4 foot-pounds more torque, too. Power to the people!

Maybe Triumph still has a thing or two to learn about the American market? -David Edwards, Editor-in-Chief

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontOklahoma Hits Home

August 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsGood Company

August 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCThunder Bolts

August 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupBritten To Build Indians

August 1995 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupBikes Will Be Made In the Usa, Says Indian's New Chieftain

August 1995 By Alan Cathcart