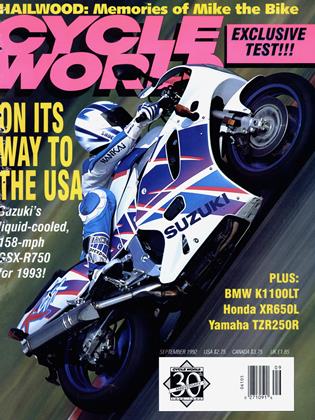

MEMORIES OF MIKE the BIKE

ELEVEN YEARS AFTER HIS DEATH, MIKE HAILWOOD'S LEGEND STILL BURNS BRIGHT

PETE LYONS

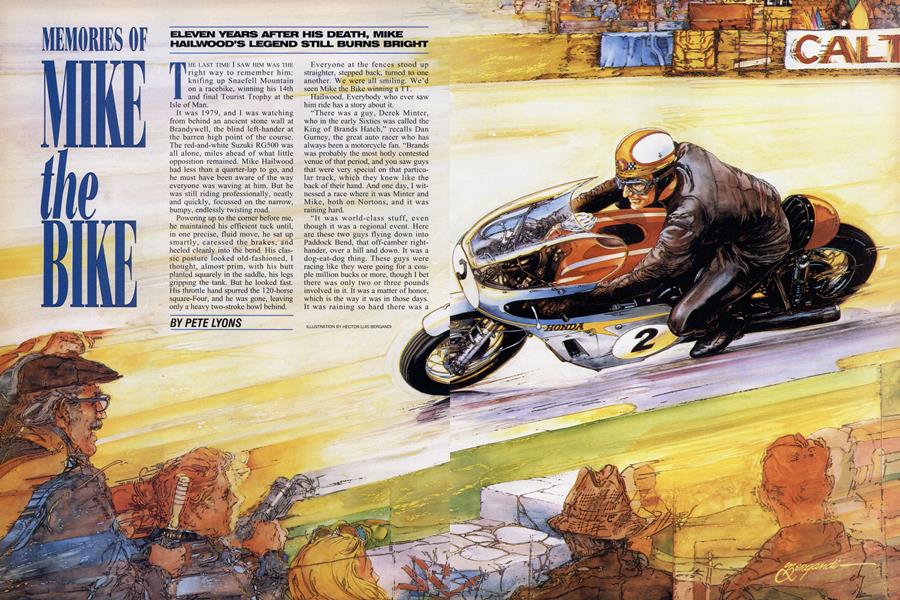

THE LAST TIME I SAW HIM WAS THE right way to remember him: knifing up Snaefell Mountain on a racebike, winning his 14th and final Tourist Trophy at the Isle of Man.

It was 1979, and I was watching from behind an ancient stone wall at Brandywell, the blind left-hander at the barren high point of the course. The red-and-white Suzuki RG500 was all alone, miles ahead of what little opposition remained. Mike Hailwood had less than a quarter-lap to go, and he must have been aware of the way everyone was waving at him. But he was still riding professionally, neatly and quickly, focussed on the narrow, bumpy, endlessly twisting road.

Powering up to the comer before me, he maintained his efficient tuck until, in one precise, fluid move, he sat up smartly, caressed the brakes, and heeled cleanly into the bend. His classic posture looked old-fashioned, I thought, almost prim, with his butt planted squarely in the saddle, his legs gripping the tank. But he looked fast. His throttle hand spurred the 120-horse square-Four, and he was gone, leaving only a heavy two-stroke howl behind.

Everyone at the fences stood up straighter, stepped back, turned to one another. We were all smiling. We’d seen Mike the Bike winning a TT.

Hailwood. Everybody who ever saw him ride has a story about it.

“There was a guy, Derek Minier, who in the early Sixties was called the King of Brands Hatch,” recalls Dan Gurney, the great auto racer who has always been a motorcycle fan. “Brands was probably the most hotly contested venue of that period, and you saw guys that were very special on that particular track, which they knew like the back of their hand. And one day, I witnessed a race where it was Minter and Mike, both on Nortons, and it was raining hard.

“It was world-class stuff, even though it was a regional event. Here are these two guys flying down into Paddock Bend, that off-camber righthander, over a hill and down. It was a dog-eat-dog thing. These guys were racing like they were going for a couple million bucks or more, though I bet there was only two or three pounds involved in it. It was a matter of honor, which is the way it was in those days. It was raining so hard there was a small river cutting diagonally across the track in the middle of the comer, and the bikes were doing a big ‘uh-oh’ each time they went through that thing. I was in agony for about 10 laps knowing that the next lap somebody was going to go down. There was no doubt in my mind. And Minter went down. Broke his ankle, I believe. Mike won. It stands out in my mind as a very special moment.”

Phil Schilling, longtime editor of Cycle magazine, will never forget seeing Hailwood battling both Giacomo Agostini, on an MV Augusta, and his own notoriously foul-handling Honda around the swoops of Mosport, at the Canadian Grand Prix in 1967.

“The Honda 500 Four was obviously an incredibly difficult motorcycle to ride and it did scary things. I remember standing down near the hairpin, and the first time I saw those guys come over that rise and down this diving left-hander, honest to God, I thought they were going to crash, because I’d never seen anyone come through there that fast. And damn, they were going practically two abreast through there. The MV looked composed and together, but the Honda was shaking. When it would accelerate up the straightaway, it looked like it was shaking itself from front to back. Hailwood was simply finding a way to ride a motorcycle that behaved that way. I just had never seen anything like it before.”

Stories Hailwood’s of that riding sort ability are legion. alone was enough to make him a legend with people who saw it. But Stanley Michael Bailey Hailwood also made an indelible impression in motorcycle racing’s record books.

Born on the fourth of April during 1940, the year of the Battle of Britain, he grew up in the English university town of Oxford. His father, Stan, himself a pre-war racer, ran a large motorcycle distributorship, and the business was prosperous. Little Mike grew up in relative affluence. As a child, he enjoyed both a small motorcycle and a gas-powered toy car; he drove his mother’s XK-120 Jaguar before he could see over the steering wheel; and when he entered his first motorcycle race, at Oulton Park on Easter Monday, 1957, the just-barely 17-year-old arrived in his father’s chauffeured Bentley.

That display of ostentation earned him no credit in the overwhelmingly working-class world of British motorcycling. Nor did his finishing position, 11th on a borrowed 125cc MV. But a few months later, after a further 17 races, he had won four and earned his International license, a feat that usually took a new rider two years. That August, back at Oulton Park on a 250, young master Hailwood set about chasing established star John Surtees. He crashed and broke a collarbone.

He also bought one of Surtees’ old racebikes, an NSU, and that winter, leaving his colleagues to freeze as they rebuilt their machinery in their garden sheds, the well-to-do teenager went to South Africa. He came back as South African National Champion. At the end of the following summer, he was British National Champion in three classes: 125, 250 and 350cc. He’d also earned fourth-place points in the 250cc GP championship despite missing two rounds. And he’d ventured to the storied Isle of Man for the first time, where he raced in four classes, coming home third in the 250 TT over the epic 37mile public-road circuit. The overall tally for 1958: 74 victories, with 38 race or lap records. Press and public were going bonkers over “Mike the Bike.”

In 1959, he was invited to join the Ducati factory team, and the 19-yearold became the youngest rider ever to win an international championship race, the 125cc class on the fearsome road course at Dundrod, Northern Ireland. At the end of 1961, riding a Honda, Hailwood was 250cc World Champion.

Eight the 500 more class, world he titles won followed. with MV In Augusta in 1962, ’63, ’64 and ’65. Then, fed up with the difficult Count Dominico Augusta and thinking Soichiro Honda’s approach more promising, he switched camps again. He took the 250 and 350cc titles in 1966 and ’67, though MV’s Agostini just edged him out in the 500cc class both seasons. But at the end of all those years he brought home 12 Tourist Trophies from the Isle of Man, a feat some fans would count his greatest. In 1967, in what many consider the ultimate IoM contest, Hailwood wrestled the monstrous Honda 500 to a stunning lap record-108 mph-that would stand for years. He won that race with his loosened twistgrip tied on with a handkerchief during a pit stop, and despite pleas from the usually unrelenting Stan to quit. “You must be mad,” retorted his son with a hard look, and screamed away in pursuit of arch-rival Agostini.

A bom racer to the bone; that’s what Mike the Bike’s adoring public saw. A colorful figure despite the scuffed black leathers, the tattered boots, the chips in his gold-and-red-trimmed helmet. Fair of hair and blue of eye, built like a boxer, perpetually tanned, he was almost idyllically good-looking, and obviously lived the sort of life fans dream of: speed, sun, sex.

Quickly bored, fond of parties and pranks, Hailwood had the typical racer’s disregard of convention, and his love of mischief could trespass upon scandal. Yet to close friends he’d sometimes express self-doubt and regret. He’d speak incongruously of what he called “my anti-social streak.” He’d grouse about aging too quickly. He gnawed his fingernails, and slept poorly. He drank too much, say some, and drove too fast.

About his racing, though, he was a thorough professional, resolute to return his backers, and his fans, full value for their money. That cost him innumerable race mornings spent paleskinned and shaking, his stomach a miserable knot of anxiety. The drop of the flag, of course, transformed him into a marvel of nerveless daring. At speed, Hailwood could meld so gracefully with his machine that it was like watching music.

A BOII~ HACER TO Tilt BONE; TIE~T'S I%1JAT MIKE Tilt BIKE'S ADORING PUBLIC SAW.

That music stopped, temporarily, in 1968, when, oddly, Honda paid Mike the Bike to stay out of the saddle. The company left motorcycle racing to build up its presence in automobiles. So Hailwood did the same. He’d had a fling on four wheels a few years earlier, when he’d been half-owner of a secondstring Formula One team. He’d managed a few good showings, including a world championship point for sixth place on the tight streets of Monaco in 1964, but overall, his auto-racing experience had been less than positive.

This time around, it went better. He started placing well with big Ferrari and Ford sports cars, including third in the Le Mans 24-Hour in 1969. In powerful Formula 5000 open-wheelers he did even better, winning a number of races in equipment built by John Surtees. That other great former motorcyclist-and 1964 automotive world champion with Ferrari-also fabricated Formula One cars, and Hailwood put one into the lead of the 1971 Italian GP before finishing fourth. The following year, Mike ran both F-l and Formula Two for Surtees, and earned the European F-2 Championship. In F-l, he nearly won two GPs, scored one second place, set one fastest race lap, and wound up eighth in points. In a non-title round that year, he was beating a field that included eventual champion Emerson Fittipaldi until his car’s engine melted.

The dry data is important, because they refute an unfair but widespread impression that Hailwood the ex-biker was useless on four wheels. Yes, he did have his problems. He freely admitted he lacked the mechanical aptitude, specifically the scientific understanding of vehicular dynamics, that even then was beginning to be vital in car racing. And he acknowledged that, at first, he did slide off the road a bit too often. He revealed these and other frank feelings in his enthralling 1968 book, Hailwood, cowritten with Ted Macaulley.

Perhaps a greater handicap was the way the fun-loving, fiercely independent Hailwood too often got himself crossways to the more class-conscious members of European society. In his early riding days, some rivals called him a rich kid whose father bought him success. It was a slander he soon quashed by incredibly gutsy track performances-more than once he finished a race with blood coming through holes worn in his boot toes, which he used as feelers to help him gauge lean angles during cornering. But in some parts of the car world, Hailwood encountered the same prejudice in reverse: “This motorcyclist chap; charming, and all that, but he’s just not one of us, old boy.”

BY ALL THE RU~ COMMON SENSE, IIAILWOOD'S DECISiON TO RIDE AGAIN WiS ASTOUNDINGLY, DELIGHTFULLY FOOLISH.

Well, both I kinds watched of him racing. in combat At South in Africa’s Kyalami circuit in 1973, I also watched him wade into flames, his own suit alight, to help rescue fellow-driver Clay Regazzoni from a crashed BRM. He was given a special award for that. That season finally went down the drain with chronic mechanical troubles, and for 1974, he switched to the ultra-reliable McLaren team. He drove a third car in company with 1967 World Champion Denny Hulme and Fittipaldi, who was on his way to a second title. Hailwood outqualified them both at Monaco, split them on the grid at six other grands prix, finished races ahead of one or the other four times, and in South Africa, he beat them both for third place.

Then, late in the season at the Nrburgring, he had outlasted both teammates and was running wheel-towheel with the two brilliant Lotus drivers, Ronnie Peterson and Jacky Ickx, fighting for fourth, when on the next-to-last time over the Pflanzgarten jump, he landed wrong and veered into the guardrail. The McLaren’s aluminum monocoque crumpled and snapped his right leg in three places. It was Hailwood’s last car race.

A lion with his teeth pulled is one of racing’s more melancholy figures. Hailwood disappeared into restless retirement in remote New Zealand, running a marine business to keep active, and maybe to keep from thinking about his glory years. Until one day, with his leg healed well enough to let him get around without limping too much, the idea of riding one more TT came up.

I remember how the news went around car circles. “He must be crazy,” was the general opinion. The cycle circle had a similar reaction, except that it was tempered with joy. “Nobody expected Mike Hailwood ever to ride a motorcycle in competition again,” wrote Barry Coleman for Cycle World. “His decision to do so was astounding, and delightful. And by all the rules of common sense, astoundingly, delightfully foolish.”

But one of his friends came back from a New Zealand visit to tell us what the madcap notion meant to Mike. “He was going stir-crazy out there. You wait ’til you see him now, he’s a different bloke. Not an ounce of fat on him anymore and he’s been working out like a man possessed. His chest and arms, they’re like rocks...”

But the man was 38, and he’d been out of TT action for 1 1 years. Realistically, rationally, there was no hope. Hailwood was just going to tarnish his own image.

Instead, he won.

That was was the Formula 1978, and One what event he on won a beefed-up Ducati streetbike. His forays in three other TT classes didn’t work out so well, though he racked up some fast practice times. But at little Mallory Park a week later, racing the Ducati against hardened shortcircuit scratchers, he won again.

Had he quit there, his brief comeback might have gone down as an impressive but ultimately unclassifiable anomaly, a bright blip in a fading career. But the following year, he chose to risk it all again, and rode the Suzuki RG500 to his 14th TT triumph. On the way, he set a class lap record at 114 mph. Nobody who was there that day had any doubt that Mike the Bike had cemented his place among the greatest riders in history.

A few days later, he broke a collarbone again in a practice crash at Donington, and he did stop then. He was married, after all, with two kids. They were both with him one dismal night in March, 1981, when he drove into a truck that was making a U-turn. Son David survived. Mike and his daughter, Michelle, didn’t.

Racing may inure us to such losses, somewhat, but there will always be a special poignancy suffusing memories of Mike Hailwood. For all he achieved on two wheels, he never accomplished what he hoped to, and was capable of, on four.

Dan Gurney, who knew Hailwood well and admired him deeply, saw his automotive period this way: “He was such a natural on a motorcycle-he could do it unconsciously-that it was sort of a rude awakening that the same thing couldn’t be done with a car. He probably never managed to come to grips with what it took to understand it. That can happen very easily. But he was very open about it, which made me sad because he was such a talented guy. If he had had the chance to become a little more familiar with it, I’m sure he would have been very, very good as a Formula One driver. He was good, but he wasn’t what he wanted to be, which was how good he was on a motorcycle. He wasn’t ‘Mike the Car.’ I know that he was just down on himself and he more-or-less felt that he had somehow failed. That bothers me,” says Gurney.

Ah, but on bikes, in his prime, Mike was magic.

“My feeling,” says Phil Schilling, “was that when I saw Hailwood in ’67, I saw him at the absolute peak. It was wonderful. Like Freddie Spencer, he could find a way to ride things that other people would say, ‘It’s not ridable.’ That made him very special, and I think practically invincible.

HE’D GROUSE ABOUT AGING TOO QUICKLY. HE GNAWED HIS FINGERNAILS, AND SLEPT POORLY. HE DRANK TOO MUCH, SOME SAY, AND DROVE TOO FAST.

“I don’t think there was anyone who, in their heart of hearts, believed that they were as good as Hailwood.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAn American Racer

September 1992 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsElectra-Glide

September 1992 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCOily Harry

September 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1992 -

Roundup

RoundupNorton's Future Assured, Maybe

September 1992 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupShoei Reorganizes

September 1992 By Yasushi Ichikawa