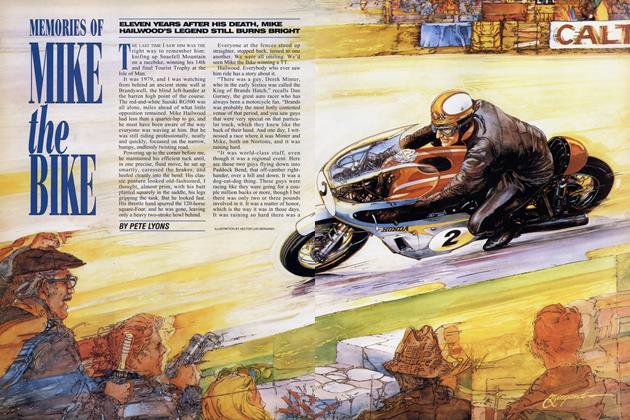

MIKE THE BIKE'S LAST RIDE

“I've been wanting to see a TT for 25 years and if I had to miss all the ones that have gone before, I can’t think of a better first one.”

Pete Lyons

There were sheep up here with me last night, but by dawn they'd cleared out. I can imagine them sniffing disdainfully and turning away from my car in their meadow, trekking over the hilltop to avoid my unseemly invasion of their ancient privacy. “Oh, oh. The first of them."

The thin morning light showed just the hunchshouldered, barren brownygrass backbone of the island. There was a raggy grey doudcap oppressing Snaefell’s summit and there wasn’t much world showing out beyond the mist. It felt very old up here and remote. I found myself thinking of Runes and Barrow-wights and.sitting up in the back seat of my “hire car.”holding a sleeping bag around my arms in a cold that was more perceived than actual, I half fancied that were 1 to turn around. I’d spy Frodo's band of wayfarers toiling in

resolute single file up the empty mountainside.

These hills are old. Their age dwarfs the official Thousand Years of the Tynwald, the parliament set up by Danish Vikings who captured the island something like that long ago. The Kingdom of Mann is celebrating that distant event this summer in its jovially honest-hearted enthusiasm for tourism, but this little bump in the Irish Sea was hoary long before the longships came.

There are some in the world of motorcycling w ho hold the Tourist Trophy races to be overly ancient themselves, that this form of the sport died, or ought to have died, decades ago. Listen to people who don't support the TT and you hear the most distressing things about what’s wrong with it. But I’ve come here prepared to be glad I did and the first thing I've been

noticing is that, for something that’s supposed to be obsolete, there are an awful lot of people w ho have come a long way to be part of it.

All morning now' the noise of hundreds and hundreds of cars and bikes has been swelling across the rolling pastures with a sound almost like surf on the invisible shores of the sea far below'. They began to arrive with the dawn light, riding and driving along the TT course itself from their hotels and guest houses down in Douglas and Ramsey, parking in orderly clots in cul-de-sacs and settling in crowlike black flocks on the grassy verges and stone walls. Now', not long before the start of the Senior, they delineate the circuit as far as it can be seen from here, forming a winding black line across the brown hills.

I’ve antigravitated to the highest part of the course, an elevation of 1384 ft. according to my map, at a small stone hut they call the Second Mountain Box on the outside of a fast, blind lefthander named Brandywell. I can see back along the course to the Bungalow; the actual bungalow is long gone, but there’s a cafe and a motor museum there, a crossing for the electric mountain railway line and a spectator bridge. A lot of people are clustered there and on back from there, a line of them showing the fast swerves coming along the mountainside from the shoulder, miles away, that marks the Verandah corner. When the first bikes pop into view there, they’ll be tiny bright specks shooting along a thin, dark line of spectators.

It'll take them a w hile to get here. We’re about 30 mi. out around the lap.

Everyone tends to cluster loosely around portable radios, dozens of which replicate Manx Radio’s cheerful and learned job of setting the scene. We’ll want this: the TT, like the Targa Florio and the Mille Miglia of sad, hallowed memory, is one race you “watch” more with your mind’s eye than by actually seeing it. Here on the open slopes of Snaefell we’ve got a w ider view than at most places around the circuit, but we won’t have the riders in sight for as much as 5 percent of their race. To “see” the rest of it. you need to have been around and around the 373/4 mi. yourself. You have to have been down the wild, bumpy plunge of Bray Hill, with its sidewalks, lampposts, cement garden walls and brick cottages close at your elbows. You must have been on around to Braddan Bridge, to Ballacraine, to Barregarrow and Ballaugh . . .

They’re starting! Down there in the Glencrutchery Road, between the grandstand and the long “leaderboard,” they’re pushing off in pairs at 10 sec. intervals and over the radio it sounds like a carrier strike going off. You can picture the quick patter

of leathered feet, the bounce into the scanty little saddle; you hear the abrupt whine of two-strokes burning away and imagine the front wheels lifting at the first shift; the first pair of bikes is still wailing back into the microphones as the second pair bursts on-line. There is a strong sense of urgency coming through from that rapid succession of launches and suddenly I feel my blood going warm. This really is a race.

All along our miles of meadow, people have stirred, turned toward the track, brought up programs or scraps of paper and begun marking down the information coming to us through the radios. At the sharp righthander in front of the hotel at Ballacraine. 7 mi. out. a new radio voice cuts into the ongoing description from the startline to inform us that the first riders are going through. Their engines screaming up through the gears in the background. he describes their order and their colors. When the first few of them have gone by, he gives us a quick calculation of their relative positions in the race: it’s Mick Grant 4 sec. up on corrected time on Mike Hailwood.

Having done my homework. I applaud the way the race organizers have arranged the starting lineup—it’s not done by practice times here, for these are the two men most likely to be making a race of today’s Senior TT (for 500cc pure-racing machines). Here they are close together on the road near the head of the pack, as well as close in the race.

Grant, the only man riding today who’s ever been around the lap in less than 20 min. (19:48, 114.33 mph. on a 750) is obviously one of the strongest potential contenders, but he’s working a brutal handicap. Eight days ago, racing in Ireland on another road circuit, he came off when the chain adjuster broke and he went into a wall. His pelvis is cracked and he’s nursing

bruises and pulled muscles all over his body. That he’s out of bed is impressive; that he’s leading the Senior TT right now7 is something else. I don't want to try to imagine what hand-on-the-thigh acrobatics and the hammering from the road surface are doing to him.

From his window above the pub in the Raven Hotel, the commentator at Ballaugh Bridge times the first bikes leaping over the humpback and gives us the corrected figures. Hailwood, sounding to our man like he’s in the wrong gear for a moment, has won back a second. Speculation follows: this is one of the smoothest parts of the course and Grant has the desperately rough Sulby Straight still ahead . . .

From Parliament Square in Ramsey, right-left flick through wall-to-wall spectators. Hailwood is again in too high a gear, slipping the clutch on the getaway, and has fallen again to four seconds shy of Grant. Grant, says our eyewitness, looks beautiful. “He just pops it over and waits for the pain in the back of his head.” Mick Grant is still leading the race, he’s magnificent, but he’s still got 5'/i laps of this ahead of him and I can’t believe he can last.

They’re on the Mountain now and everybody at Brandy we 11 is afoot at the fences. It'll only be a few moments now. Eyes peer dow n to the Verandah and—yes! Tiny, bright, incredibly quick motorcycles are flicking around the shoulder and coursing the mountainside. It's about, ah, make that about 16V2 min. since they left the startline. Damn. Trying hard in the car, it took me something like 45 min. to get this far.

Watching the distance. I’ve neglected to grab a place at the fence. Too many people to get a view as the riders approach us. All I can see are flashes of color, quick glimpses of bikes as they arc into Brandywell. First one on the road, blue and white, that’s No. 2, who started in the first wave, Billie Guthrie. Next one on the road is supposed to be Hailwood, No. 8. Yeah, here he is— that’s The Bike, alright. Quick red and white profile flash: that’s exactly how' he looked at Donington last summer, sitting up easy on the machine, his butt square in the saddle, his knees tucked firmly in against the tank. Mike Hailwood’s riding style in his comeback has been warming the cockles of all the old purists’ hearts. He’s out of an earlier era than these modern young orangutans who hang out all over the bike in the corners. Hailwood looks a little old fashioned. He looks almost prim. But he also looks damn fast. They may want to rethink this aircooledknee stuff.

Mainly, though, Mike the Bike looks like he knows what he’s doing.

And here’s Tony Rutter, then several more. Grant and Alex George; they’re coming sometimes all alone, sometimes in dices of two and even three, but I imagine each man is riding his own race, striving to hold himself out of head-to-head runs at the man ahead. They heel into the lefthander in smooth, efficient, lovely arcs like the Black Sheep peeling into a dive. The riders will, for this instant, have nothing visible on their down side but grass bank and drystone wall, nothing beyond their throttle hands but pale, empty air. The ripples in the old road surface make their tires chatter and the bikes snake a little. Their ugly two-stroke noise chases away after them on the drop down toward Windy Corner, under the next saddle along the Mountain. Then they have the frightfully quick treble left of the Thirtythird Milestone, the cramped stone walls of Kepple Gate and Sarah’s Cottage, the plunge down to The Creg, to Brandish, to Hillberry . . . only a few' more miles before the tight skirl around Governor's Bridge hairpin and the flat-out run through the pits and the end of the lap. They’ve got to do this a total of six times. It’ll be another 30 mi. and just over 15 min. before we see them again. 1 keep failing to imagine what 226 mi. of this must be like. It's partly the idea of holding 120-odd horses in my right hand that gives me trouble. You’d have to keep opening the throttle, you see.

Last week in Ulster, in the same event that Mick Grant crashed, another rider named Tom Herron died. His face, a little eerily, smiles out from a magazine in front of me. It couldn't have been long ago that he helped Motorcycle Racing put together an excellent four-page article describing the TT course from a rider’s point of view. I held it open in my lap as I went around and around, trying to “learn” the track as best I could. I’d complete a section and pull over (steady hurtle of bikers past my right ear, it was “Mad Sunday”) and read up on the next few corners before tackling them.

Bray Hill: “First, going over the lights at the top pull back on the forks to make the machine do a small wheelie so that you steer to the left and then to the right on the approach to the hill proper ... I try to make sure the bike does not come up too high on these as it then tends to go away from me a bit.” His 750 would be doing about 155 at this point.

Union Mills, where Herron said the late afternoon sun is in your eyes: “After going through the dip and back into the open you just cannot see a thing for two or three seconds so you must be in the proper part of the road because of that.”

Laurel Bank: “Unknown to a lot of people it is possible to go in there at a hell of a speed and just shut it off and roll the whole way round. You think you are going to run out of road, but you never do.”

Up Creg Willy’s: “It is possible to go all the way up through there flat out on a 750 Yamaha now, but I have only done it tw ice in my life. Once I felt safe and the other I was actually running along beside the bike . . .”

The Eleventh Milestone, a double right followed immediately by a double lelt, down between farm field hedges: “. . . one of those super corners that if you get it right you feel like going back, wheeling the bike up the field and having a go again.” But there are 2634 mi. left.

“Graze the hedge on the way in and just as you are doing that you are already changing direction for the right . . .

“There is a very bad bump there and you have to ride the footrests . . .

“. . . one of those places where there is positively nothing you can do. You are completely in nature’s hands.

“. . . you should pass over a manhole cover, which in the wet gives a bit of a twitch . . .

“. . . past a hedge on the right w hich you should just feel touching the side of your helmet . . .”

Or the bumpy, treeshadowed straight leading to the village of Sulby: “Now that is something out of this world on a 750 Yamaha. You have to consciously brace yourself, arse in the seat, elbows against the tank and your knees—and hang on like blue hell. I keep bobbing up and down and pulling on the front forks and wheelie up there as far as I can go. When that front w heel hits the deck it is just one big speed wobble.” He thinks he’s going about 160 mph “if the back wheel is on the road long enough to pull you through.’

Tom Herron was able to describe most of the TT course wfith hair-raising precision, but he admitted in his Motorcycle Racing story that parts of the climb up Snaefell mountain weren’t firmly in his mind. “There is a treble lefthander coming into Guthries which is always a problem. In fact, the only person I have seen go through there properly is Mike Hailwood last year. He must have been on the right line. I learned it that night and forgot it again the next day.

One of the compelling things about the TT is that, unlike almost every other road race being held anywhere in the world these days, there is so much of the road and it is so complex that no man can ever have honestly learned it completely. One only gets a few laps of practice, even though a week is devoted to practice. Weather changes from hour to hour, sometimes, and from year to year there are always alterations to the road itself.

“Scratching” around an English short circuit, racing against World Champions on a Grand Prix track; these are worthy things. But the Isle of Man is a different kind of racing. More than anywhere, I think, you race the road here. You race yourself, to an extent, too.

“You’re not going to believe it when you get there,” a friend said when he heard my plan to come. “You’re going to drive around and you’re going to say to yourself, ‘I don’t believe this.’ ”

On my first lap with my little rented tin box (how I wish I’d been able to borrow a bike) I joined the circuit at Quarter Bridge and I hadn’t gone 50 yards when I started saying precisely the words my friend had said I would. On the right side of the road was a curbstone, a narrow walkway and a 5 ft. wall made of slabs of a dark, brittlelooking stone. Slate? Atop the horizontal courses a final row of slabs had been cemented into place vertically, just as builders of some walls top them with broken glass. A double row of slatey teeth marched down the entire length of the wall, jagged-edged and about 10 in. high. They caught the sunlight and cast shadows on each other. They had the evil feeling of the teeth of a mowing machine. I looked back at the Quarter Bridge corner and I thought about 120 bhp acceleration up through second gear, third gear, fourth and I said to myself, “I don’t believe this.” There are places around the course where, against a particularly abrupt corner of a stone wall, or against the farther side of a gate, or against a lamppost or a house or a tree, the race organizers have piled mattresses of old hay wrapped in plastic bags that say Dunlop. Going down into Greeba you can even spot a wooden, redpainted, regulation British telephone box swaddled in sacks of hay and a chuckle will burst from your throat. But, in their hundreds, the cushioned obstacles are scarcely even a token. Each abutment, each post, each wire fence defended with such pathetic hope is outnumbered by thousands of naked others, each seeming to lean out toward the racing line with the sullen, blackhorned menace of a disturbed Cape buffalo. This race track has 15Vi mi. of edges and almost any of it could kill you.

I think I’m in love with it.

As measured down there in the Glencrutchery Road and posted on the long black scoreboard, the official race order at the end of the first lap was Grant, who'd finished it in 20:17.2 (111.59) and led George by 4.6 sec. Hailwood was a farther 2.6 sec. back. All three were riding 500cc Suzukis. although Alex George called his a “Cagiva.” The next machine, at 20:33.2 (110.14), was Charlie Williams’ 350 Yamaha.

At Ballaugh Bridge on the second lap Hailwood had taken over the lead on the road and somewhere on the Mountain climb he pulled out enough time on George and Grant to lead the race as well. For one reason and another he’d only done five laps of practice on the bike—a year-old RG500 GP machine—and none at all with the 10 gal. fuel tank he’d decided to fit on it. Now, with some experience on it and some fuel gone from it, he began pushing harder and at the end of the second lap his time was 19:57.4 (113.43). That was better than he’d gone all last year, on Yamaha or Ducati.

George, taking over second place by about 3 sec., shot through to the brink of Bray Hill after Hailwood, but Grant braked down into the refueling lane. He’d chosen a smaller tank with its requirement for two pit stops and it dropped him to fourth place, behind Steve Ward—yes, on another Suzuki.

Hailwood was warmed right through now and ripped around the third lap so fast that, even slowing down for his pit stop, his time was 19:51.2 (114.02). That was a new lap record for the class and but 3.2 sec. off Grant’s absolute record, set the year before on a Kawasaki 750. The observers at the pits said the leader had come in and gone out with calm.

George, already falling inexorably behind, spent a bit longer in the pits too and rejoined about 20 sec. back. Tony Rutter (Suzuki) was up to third overall, if narrowly from Williams, for Ward had been given a mechanical black flag at Ramsey for inspection. Nothing amiss and a credit was added to his time, but he had still dropped to sixth.

Grant was nowhere. Or rather, he was at Kate’s Cottage, coasting downhill toward Creg-ny-Baa with a crankshaft broken. Well, there's a pub there.

George was over a minute back when he stopped unexpectedly at the pits the fourth time through. His team gave him a quick plug change and sent him on, but he never appeared again. The ignition had packed up.

Williams’ little Yam ran out of gas. Billie Guthrie moved his big Suzuki up to third at the end of the fourth lap. but later on he ran out of fuel too. Tony Rutter filtered up to second finally, but well over 2 min. back from the now cruising Hailwood. Dennis Ireland (Suzy) was third.

The hazy sky is letting some sun through to the slopes of the Mountain, now, and since he is by a long way the first man on the road he ought to be easy to spot at the Verandah. He’s been regular, ticking off 20-min. laps like hands on a big, 37-milein-diameter clock face, but as we wait for him to burst into view this last time I wonder if mine is the only stomach cramped in little knots for him. I want him to succeed at this.

I’ve been thinking back. It was 1961 when he won his first TT here, the Senior, I believe. I wasn’t here that day, but I was in Europe and sometime or other that summer I rode my old Norton out to Brands Hatch to watch a bike race. I scrambled up the bank to the outside of Clearways corner—the racing was already under way— and I arrived breathless at precisely the right instant to see one of the bikes in a pack right in front of me give a sudden wobble and go down on the high side. A figure wearing black leathers went flying through the air, clearly visible above the heads of the spectators. I remember thinking how graceful and relaxed his arms and legs looked. The “tannoy” announced that it was this new bloke, this Hailwood. I read the next day that he'd got off with only a thumb broken.

I mentioned that to him once, a lot of years later when he was racing Formula One cars. He didn’t own up to remembering the incident, so I described it in graphic detail. He shuddered. “Oooh. Sounds dangerous, chap!”

He’s always been one of those people you warm to immediately. He was liked by the FI crowd at least partly because he always seemed like a throw back in his style of living to a gayer era. The Grand Prix Circus was coming back from Kyalami all together on a charter one Sunday night and somewhere about 2 a.m. over the blackest of Africa, there was a convivial little group clustered around his seat in the middle of the 747. Most people elsewhere were trying to sleep, but chez Hailwood was all bright reading lights and bubbling glassfuls of champagne. I tried to slip by unobtrusively on my way to the john, but at the last second Hailwood’s foot went out and brought me down in a heap. “Here, chap. I'm inviting you to me birthday party.”

He went through a period with John Surtees of, shall we say, mechanical uncertainty and one Saturday in Austria, the car having already stranded him out on the course several times during practice, he said he really didn’t mind, he was prepared: he showed me the paperback novel he was carrying in his suit pocket.

The first time I ever dared speak to him was during one of the 12-hours at Sebring. I’d ridden a Triumph 650 down and was full enough of myself to mention it by way of making conversation. Oh, really, that was interesting, he said pleasantly, he was riding a 750 Triple just now. Oh. say, asks I, what sort of tires did he have on it (might as well get the Word on tires, don’t you know.) His face went a little blank. Tires? Dunno about tires. Never thought to look.

Uhm. The conversation lagged a little. He stirred again; wouldn't actually have the bike except they’d given it to him; bit on the expensive side, you know.

Uh huh. Ah, let’s see, what sort of street car do you drive, Mr. Hailwood? His face lit up, he could talk about that. An Iso Grifo. Smashing car. Italian car with a Chevy engine. Really quick. Like it.

In those days he was living in two places, so I asked him if he kept the Iso Grifo in England or out in South Africa.

His face went uncomfortable again. “Uh, well. I’ve two, actually. One in England and one in Africa.”

You never did get out of Hailwood quite what you expected, he was always interesting to talk to. The only time, though, that I ever caught a glimpse behind what I think of as his shy crust was early on a Sunday morning at Interlagos, in Brazil. His McLaren happened to be pitted at the end of the pits you came in at from tow n and so he was the first driver I ran into. He greeted me with his customary good cheer but as he spoke his voice trembled. I looked closer and his face was pale. His shoulders and arms and hands were quivering. My God, Mike, what’s wrong with you? Food poisoning?

“Naw, I’m always like this. It'll go away once I get in the car.”

Damn, I hope that bike lasts today. I don’t know if it’s anything more than the fact that we’re within weeks of the same age, but I’ve been rooting for him during his motorcycling comeback with a goodwill that's almost desperate. I remember how' the word went through the car-racing world when it became known that, down there in sybaritic retirement in New' Zealand, Mike Hailwood had decided to enter the Isle of Man TT. Christ, he must be mad, was the general reaction, but one of his friends who had just come back from seeing him told us what the project had meant to him. “He was going stir-crazy out there. You w;ait ’til you see him now. he’s a different bloke. Not an ounce of fat on him anymore and he’s been working out like a man possessed. His chest and arms; they're like rocks ...”

I’ve been wanting to see a TT for 25 years and, if I had to miss all the ones that have gone before, I can’t think of a better first one. It’s about time, he’s been on his way up from Parliament Square the right amount of time, the spectators are stirring—

Right-oh, there's the Bike, knifing along the road. How grand he must feel, the airflow bathing his shoulders, that heavy two-stroke howl behind him. He’s half sitting up. he looks almost like he’s touring and he must be quite aware of the way everybody is waving programs and papers at him. But his line is just as fine as before. He peels off into the lefthand entry to the Bungalow exactly where he did the five previous times, heels to just the same angle, brushes his left toe precisely as close to the grass at the apex. He straightens up and flickers over the railway lines and then, acceleraing hard, banks to the right and grazes the grass under the footbridge.

Down on the tank, up the rise to Brandywell. Power stays hard on through a preliminary righthand kink. Then, in one brisk, efficient move, he sits up, squeezes on some brakes—the machine gives a couple of irritable little fishtails as the tires find some ripples—drops a couple of gears and then slants easily into the lefthander. He’s around the bank and gone, the winner. All we have is the engine to hear, now, and that fades rapidly. There’s nothing left but the happy babble of people turning to each other with a thousand ways of saying. Did you see that?

Mike Hailwood’s last official race was supposed to be at Donington Park, after the loM. During practice before the race, Hailwood crashed. His collarbone was broken and pins were inserted in his neck. He checked out of the hospital, against doctor's orders, on race day. so he could ride in a car and at least be seen by the people who’d come to watch him ride.

They had to help him walk from the car to the rostrum.

Mike the Bike always did give value for money.