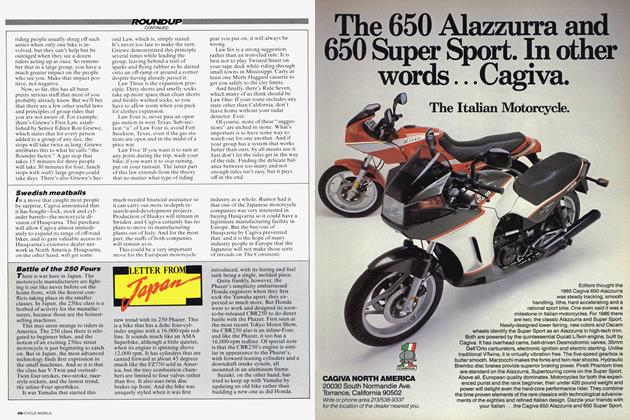

THE SUPERTOURERS

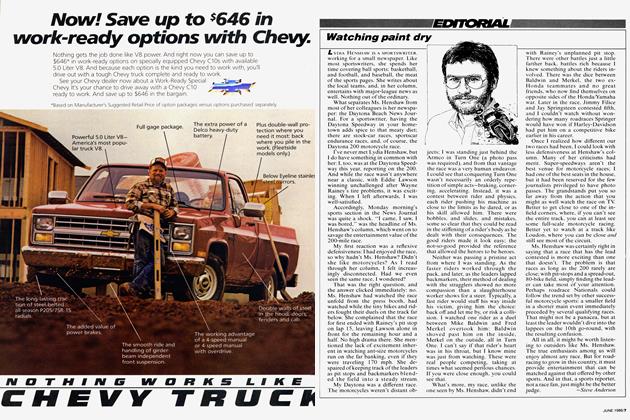

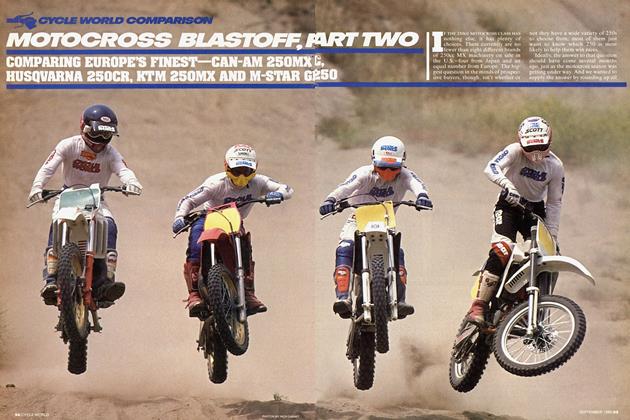

CYCLE WORLD COMPARISON

Six ways to discover America

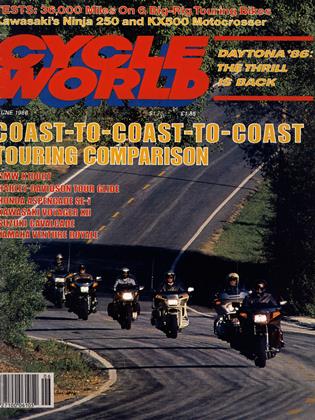

LORD KNOWS. IT’S TOUGH enough to resist the call of the open road under normal circumstances. But factor in two weeks of open time, a garage full of the best touring motorcycles available, with another one waiting in Nebraska, and it’s time to start packing the company credit cards and gathering up the road maps.

Which is just what a team of Cycle World riders did. During the last days of winter we set out from our Newport Beach, California, offices, bound for Daytona Beach, Florida, and the annual Cycle Week festivities. Our modes of transportation were the top-drawer touring bikes from the four Japanese companies, and one each from America and Germany. And our goal was not just to have fun in the sun and enjoy the races in the world capitol of speed, but to ride from the Pacific to the Atlantic and back again in search of the ultimate all-American touring bike.

Honda’s entry in our coast-tocoast-to-coast comparison was the Gold Wing Aspencade SE-i. The 1985 Aspencade won the touring category in Cycle World’s annual Ten Best awards presentation last year, so the 1986 Wing came into this comparison with the home-court advantage. Our test SE-i started the crosscountry adventure with 10,000 miles already on the odometer, racked up as part of a long-term evaluation we’re conducting on the machine. But before leaving, the Wing was treated to new OEM tires and a major servicing at a local dealer, including

an overhaul of the bike’s suspensionleveling system, which had been giving us problems.

Suzuki provided a new Cavalcade LX, a bike unchanged from the debut-model that so impressed us last year. We would have much preferred to test the refined LXE model, with its fairing lowers and four-speaker stereo; but that model was not yet available when we left for Daytona, although we did manage to shanghai one for a two-day riding impression a week after our return.

Yamaha, of course, anted up with its latest Venture Royale. Three years ago, the then-new Venture was good enough to wrest the title of Best Tourer away from Honda in our Ten Best competition. Since then, the Wing has come back strong and man-

aged to stay a step ahead of the Yamaha. This year, however, with some serious upgrades, including another lOOcc in the most potent engine ever to take up residence in a touring bike, the Venture is once again poised to take a shot at top billing.

The newest of the Japanese bikes is Kawasaki’s Voyager XII, a downsized and more frugally equipped tourer that supplements the 1300 Voyager but has little in common with that six-cylinder jumbobike. Our Voyager XII was so new, in fact, that a staffer had to fly to Kawasaki’s Lincoln, Nebraska, assembly plant and ride the bike south to Dallas, Texas, where he joined up with the rest of the group for the ride to the Atlantic Ocean. Like the Venture and the Cavalcade, the XII was turned over to us with just a few hundred break-in miles on the clock.

Standing up for the red-white-andblue in this touring shootout was the Harley-Davidson FLTC Tour Glide Classic. Thanks to a continuing series of upgrades, the Harley seemed ready and willing to stand in there and go toe-to-toe with the Oriental machinery. Our bike had already weathered 5000 miles and one magazine road test by the time we picked it up.

BMW’s K 1 OORT, visually and philosophically the most different machine in this comparison, almost didn't make our final cut. We had tested last year’s RT in the company of a Honda Aspencade and had come away unimpressed, disappointed, even. But BMW has been hard at work improving most of the areas we criticized last year, and has ended up with a recalibrated RT that, from outward appearances at least, promised to be more in touch with the needs of the U.S. market. A gray RT, 1000 miles showing, joined our fleet of cross-country vacationbikes.

Fourteen days after leaving the terminal gridlock that masquerades as greater Los Angeles, we were back. Behind us lay almost 6000 miles of riding, across deserts, through forests and around mountains. We rode through rain and sleet and heat, on as varied an assemblage of roads as our schedule and the weather would allow. By the time we were done, we knew which company makes the best touring bike for America.

CALIFORNIA starts out blandly HIGHWAY enough, 78 just another paved tributary that branches from the San Diego Freeway to deliver commuters to their bedroom communities. But just past Escondido the road starts to sprout curves, and it then winds past orange groves and apple orchards, climbing towards the quaint, stagecoach town of Julian. Twelve downhill miles later, 78 collides with S2, a lightly patrolled road that skulks across the desert floor and invites you to make time.

This is BMW country. But then, it was no surprise to us that the muchlighter, sport-oriented RT would pull ahead of its Winnebago-class competition when the going got twisty or the speeds approached triple-digit status. Under these conditions, the RT refuses to get ruffled; after all, this is the stuff for which it is bred.

What was surprising, though, was the Beemer’s competence on the lessdemanding portions of the ride. This is a motorcycle 100-percent better than its predecessor. The bike’s full fairing, especially with its new windscreen, offered the best protection of all six bikes, while still giving the rider the option of looking over the plexiglass, not just through it, a definite plus in wet-weather riding. The seat, out of character for a BMW, perhaps, still is a leap ahead of the previous stepped model, which could get truly uncomfortable.

All is not roses with the RT, however. If you happen to be taller than about 5-foot-10, you’ll have to get used to riding with your knees grinding against the fairing lowers. The new seat positions the rider closer to the front of the bike; and because of the seat’s bucket design, moving back is impossible. Further, while both the radio-installation kit and the tourtrunk options were welcome additions on this trip, they really aren’t up to class standards. The trunk is almost too small to serve any useful purpose, and the radio kit doesn’t have any provision for handlebarmounted controls, meaning that the rider has to reach down to the tuner, located in the left-side fairing pocket, to make adjustments.

We complained about vibration on last year’s RT, and it’s still with us this year. Once again, the left footpeg is the main culprit. Add engine heat to that not-improved list, along with gear whine, excessive fork dive and considerable shaft-drive reaction, and you’ve got a bike that can be downright infuriating at times.

BMW K100RT

WHEN BMW’S ENGINEERS DESIGNED THE K100RT, they had in mind numerous types of riding that fall under the general heading of “touring”; but the kind of open-road, getting-away-from-it-all-by-taking-it-all-with-you travel unique to America was not one of them. So it’s easy to understand why the RT hasn’t proven particularly well-suited for life on the interstates.

For 1986, however, BMW has addressed that problem by reconfiguring several key areas of the RT in an attempt to make the bike more competitive for longdistance riding, American-style. There’s now an optional radio-installation kit, for example, that includes two speakers, an antenna and all the affiliated wiring and hardware needed to mount a radio in the left side of the fairing. The only catch is that the $ 145 kit is available from BMW dealers, but the radio itself is something an owner has to locate on his own. Our test K100RT came equipped with a $687 Alpine car radio that had been mooched from the accessory people in BMW’s car division. Also available as an option is BMW’s first-ever touring trunk. At $ 1 10, it’s fairly cheap, but it’s also the smallest tail trunk we’ve seen.

As far as standard equipment is concerned, a completely new windshield replaces the radically rakedback shield used on last year’s RT. The new windscreen is wider and more vertical, and is available in three different heights. K1 OORTs are shipped from the factory without a windshield, and the dealer simply installs the shield of the buyer’s choice. Our test bike was fitted with the medium-height shield, which is two-and-a-half inches taller than the short shield, and two inches shorter than the long one.

Also new for ’86 is a two-tier bucket saddle that is considerably wider than the previous seat, and slightly lower, as well. In addition, the grab rails and the body panels below and behind the seat are now like those on BMW’s new K75 Triple.

Because many riders of previous K1 OORTs complained about vibration putting their hands and feet to sleep, the latest RTs have redesigned footpegs and footpeg mounts, closed-cell foam handgrips, and rubber knee pads on the sides of the gas tank. A lot of riders also griped about excessive heat behind the fairing, so the new model no longer has the elaborate rubber boot that completely sealed the front-fork opening in the full fairing. In the boot’s place are two air scoops that help divert more cool air back to the passenger compartment, along with a special heat shield under the gas tank to insulate the fuel from the high temperatures that exist right above the engine. And in that gas tank is a rather old-fashioned mechanical float mechanism that signals the low-fuel warning light on the instrument panel. The float replaces a high-tech but grossly inaccurate heat-sensor that attempted to do the job on last year’s K100RT.

In all other mechanical respects, the ’86 K1 OORT is identical to its predecessor. It uses the same 987cc, liquid-cooled, fuel-injected, eight-valve, dohc engine, which is an inline-Four laid over on its side. Also unchanged is the Monolever rear suspension, which not only uses a single shock, but a one-sided swingarm, as well. Unusual designs, to be sure; but just as BMW’s designers were not specifically looking to build an American-style touring motorcycle, neither were they looking to build the usual.

Still, for touring riders who scan a map for squiggly red lines, who see interstates as a necessary evil, who

demand that a bike keep its composure at go-to-jail velocities and who want something different, there simply isn’t anything else. And with the improvements made this year, BMW has made sure those riders don’t have to sacrifice quite as much to get what they want.

INTERSTATE zona and New 10 CUTS Mexico, ACROSS through ARIdesert so inhospitable that you wonder why the early western settlers didn’t stop and turn their wagons around when they reached this point. As night falls, man’s franchised contributions to the environment become camouflaged, and in the last washes of sunlight, the red mesas and craggy hills take on a positively prehistoric glow.

YAMAHA VENTURE ROYALE

THERE’S BEEN LITTLE DOUBT OVER THE PAST FEW years about which American-style touring bike is the fastest and sportiest of them all: Yamaha’s awesomely powerful, superb-handling Venture Royale has been the uncontested champion in those categories. But the Venture also has had its share of minor-but-aggravating drawbacks that have helped keep it from being a winner in all categories. Finally, however, many of those problem areas have gotten some attention for 1986.

Undoubtedly, the most improved aspect of the new Venture is its luggage. The smallish, horizontally split, detachable saddlebags that were highly criticized on previous Ventures have given way to large, horizontally split, non-detachable bags fitted with removable liners. The travel trunk also is new and bigger, and has a three-way-adjustable backrest.

Like the bags and the travel trunk, the fairing has been improved. It now includes a lower cowling that improves airflow around the engine while affording more protection for the rider’s feet.

Yamaha has improved some of the Venture Royale’s electronic equipment, as well. The cruise control now has Accelerate, Decelerate and Resume functions, all regulated by a new handlebar switch. And an added standard feature for ’86 is a 40-channel CB radio (for listening only; to transmit, you must purchase an optional microphone package). The same AM/FM/cassette system used previously has been retained this year, and it features automatic volume

control, auto-reverse on the tape deck, provisions for an intercom system, and remote radio controls for the passenger.

One area of the new Venture in which no one expected to find major improvements was the engine; it is, after all, the same basic powerplant that forms the heart of the mighty V-Max. But for ’86, the Venture’s liquid-cooled V-Four has been modified for more lowend and mid-range power. This boost has been effected through changes in cam timing, lmm-larger carburetors and, most of all, 3mm-larger bores that increase the displacement from 1198cc to 1294cc.

To cope with the stepped-up performance the engine offers, the Venture also has larger front disc brakes, along with an electronically controlled antidive that is activated by the same switch that turns on the brake lights when the front brake lever is squeezed. The air-adjustable suspension at both ends can be either automatically or manually regulated by the Venture’s on-board air compressor; but unlike the Aspencade’s system, which you can adjust while moving, you have to be stopped on the Venture, with the engine off, to make any air-pressure changes.

That’s one of the few drawbacks on the new Venture left over from previous models. But complaints of that sort will be few and far between on this bike, because Yamaha has fixed just about everything that riders complained about on previous Ventures—and in the case of the engine, even improved a few things that not a living soul ever griped about.

With hundreds of miles still to go, a radar detector doing sentry duty and the CB tuned to Channel 19, it’s time to let the hammer fly; and there’s no better touring bike for that kind of assignment than the Yamaha Venture. The reason, of course, is the bike’s engine, a power-laden V-Four that pumps out a staggering amount of torque, all the while accompanied by a velvety rumble that at first seems incongruous with the bike’s intended role as a touring platform. Just revving the engine at idle quickens the pulse.

But even though the engine dominates all impressions of the Venture, there are other things to like, as well.

First off, the bike’s finish drew rave reviews, even if some riders thought there was a bit too much plastic bodywork covering the frame. Even after an all-day soaking on the interstates, the Venture still looked good. Wind and rain protection from the fairing, windshield and lowers was excellent, a notch behind the BMW. Although not the most comfortable in the bunch, the Yamaha’s seat and riding position allowed for relatively painless sunup-to-sundown excursions. Equipped this year with more (and usable) luggage space, the Venture finally has the carrying capacity an upscale tourer should have. The Yamaha’s sound system also rated near the top, even if the tape deck’s location meant it had to be covered with its little plastic shield every time it rained. The inclusion of a CB receiver as standard equipment was also appreciated.

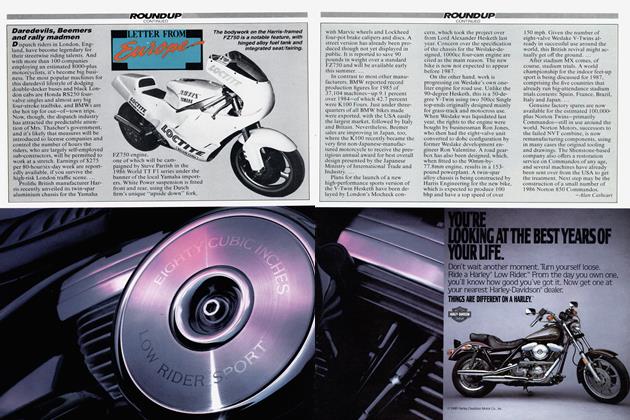

HARLEY-DAVIDSON TOUR GLIDE CLASSIC

THERE’S A CERTAIN MOLD THAT ALL TOURING bikes are expected to fit: They have to have a big fairing, saddlebags and a trunk, and above all, they have to cater to the rider’s desire for comfort. Over the years, most of the touring bikes from Japan have come to fit neatly into that mold. But in the case of the FLTC Tour Glide Classic, it seems that while Harley-Davidson is conforming to the mold in some ways, the mold also is conforming to HarleyDavidson.

After all, long before the Gold Wing was even a glimmer in some Honda designer’s eye, Harley-Davidson had a full-dress tourer, already equipped with all the over-the-road requisites. Today, the Tour Glide Classic is the top of Harley’s line, a bike cut using much the same template as those original H-D dressers.

Harley has, however, made certain concessions to the modern touring image. The company says that the Tour Glide Classic is for riders who “prefer more contemporary styling.” That primarily refers to the frame-mounted fairing, used in lieu of the more traditional Electra Glide-style, handlebar-mounted fairing. And this year the bike also has a stereo that is comparable to anything the Japanese have to offer, with features like auto seek, a CB receiver and handlebar-mounted tuning controls.

There still are many differences between Harley’s formula for touring and that of the Japanese, though. The most obvious departure is in the engine depart-

ment, where Harley uses its I339cc “Evolution” VTwin engine. The overhead valves are operated by pushrods and hydraulic, self-adjusting lifters; and instead of relying on a counterbalancer to smooth out the decidedly rough engine, Harley devised a set of rubber engine mounts to let the big V-Twin shudder and shake independently of the rest of the motorcycle. The Harley also is the only big touring bike that doesn’t use a driveshaft, but it doesn’t use a chain, either. Instead, a toothed belt is used to transfer power to the rear wheel.

This year there are numerous changes in the Harley engine, such as a new starter motor that is claimed to be 10 percent stronger, and intake and exhaust modifications that allow the bike to meet new federal noise regulations. The FLTC also now comes standard with new VDO gauges that display oil pressure and temperature, voltage and time.

Suspension-wise, the bike is unchanged. Two Japanese-made Showa air-assisted shocks still perform the rear-end duties. Likewise, the fork is made by Showa, and it even has a unique anti-dive system. Who says Harley isn’t keeping up with the times?

But even though the FLTC does have a smattering of Japanese technology, it still is very much its own machine, with certain qualities that will never be grafted onto any other motorcycle. And it’s nice to know that whatever American touring has or will become, the concept itself originated here in Americaright in mid-town Milwaukee.

Still on the plus side, the Venture’s auto-leveling system allowed us to choose from one of three automatic settings or override the system and add more air for backroad high-jinks. Add in good brakes, solid handling and an anti-dive system that actually works, and you’ve got a turnpike cruiser that doesn’t turn to jelly in the

curves.

On the down side, the Yamaha is big and feels it, especially in slowspeed going. The massive fairing/ dashboard combination, which starts just in front of the rider’s knees and spreads upward toward the windshield, doesn’t help, for it just accentuates the feeling of mass. And because the fairing sides are jam-packed with radio, CB and suspension-leveling hardware, there isn’t any smallitem storage in front of the rider. Yamaha tried to alleviate the problem by hanging two small, vinyl pouches on the back of the fairing; but the pouches are tiny, interfere with tall riders’ knees and can come adrift and fall off, as one of ours did just outside

KAWASAKI VOYAGER XII

WHEN IT COMES TO TOURING BIKES, KAWASAKI deals in extremes. It was Kawasaki a few years ago that brought us that leviathan of touring bikes, the six-cylinder, 840-pound Voyager 1300; and it is Kawasaki that has just introduced the all-new Voyager XII, one of the smaller and lighter American-style ever built. But the XII is not simply a downsized version of the 1 300; it is a completely new motorcycle from end to end.

Some engine technology for this new tourer has been borrowed from the latest Ninja sportbikes, but the XII’s engine was designed for this machine alone. The 1 196cc, liquid-cooled, dohc inline-Four has four valves per cylinder, and features hydraulic lash adjusters that completely eliminate all routine valve maintenance. And to provide ultra-smooth running, the powerplant incorporates a gear-driven, dual counterbalancing system. The engine drives through a fivespeed gearbox, but with a fifth-gear ratio that is exceptionally tall. At 55 mph in top gear, for example, the engine is spinning only at about 2500 rpm. Final drive is via shaft, with two damping systems along the way (one in the gearbox, one on the driveshaft) to absorb driveline shocks.

Cradling the engine is a three-section chassis with a removable rear sub-frame. The right downtube also is detachable to facilitate engine removal. Suspension is provided by dual shocks in the rear and a typical fork in front, with both ends offering air-adjustability. A trio of disc brakes provides the stopping power.

Naturally,the XII has all the requisite over-the-road

touring gear, such as a full fairing (that has several built-in storage compartments), roomy saddlebags and a tour trunk, with full-width light bars at the rear like those on Honda’s Aspencade. The saddlebags can be removed by taking out one pin per bag, and the tour trunk comes off by removing two wing nuts inside the storage compartment. The passenger section of the Voyager XII’s seat can be moved forward and back to give some lumbar support to the rider, and the tour trunk can also be moved fore and aft for the passenger.

As far as accessories are concerned, the Voyager has quite a few but is not “loaded.” There is no cruise control, for instance, nor is there an on-board air compressor for inflation of the fork or shocks, or a trip computer such as on the Aspencade SE-i or the 1 300 Voyager. But the XII does comes equipped with an AM/FM/cassette player and two fairing-mounted speakers. The sound system has a remote control unit on the handlebar that includes a volume control as well as the usual scan and mute functions, and there is a separate control unit for the passenger mounted on the front of the tour trunk. In addition, the XII comes standard with crash bars, bag liners and passenger footboards. The only options, for now, at least, are a CB radio and a bolt-on lighting and accessory trim kit.

So while the Voyager XII may not have all of the gadgets found on some of the other big-rig touring machines, one of its most compelling features is its relative compactness. It is smaller and lighter than its main competition, and has a low price to match.

Phoenix. Also, the cruise control lacks precision, and its use is accompanied by a bright blue light just below the ignition switch that is irritating at night. And when you temporarily cancel the cruise control, the blue beacon is joined by an equally irritating yellow counterpart labeled “Resume.”.

Still, there’s always that marvelous engine to fall back on. As one of our riders put it, “Anytime you get bored with the bells and whistles or the scenery, just crank on the throttle. The Venture feels like a V-Max, and that's entertainment.”

fLORiDA know that HIGHWAY there’s 27 more LETS to YOU the Sunshine State than orange juice, white beaches and Disney World. The road is a well-maintained, tree-lined passageway that runs easily through small towns, delivering its users to the environs of Ocala and some truly memorable scenery. Time it just right, and 27 will give you enough golden-light, postcard images of horses grazing in tidy pastures to last a lifetime, before leading you to Highway 40 and the cool green of the Ocala National Forest.

On these kinds of roads, ones that threaten visual overload, there’s no better sightseeing vehicle than the Harley-Davidson. At speeds below 75 mph, with its rubber-mounted engine throwing off just the right kinds of motorcycle feels and sounds, the FLT is a delight. It goes where it’s pointed without constantly forcing the rider to make corrections, yet it changes direction easily and positively. Its broad seat, which at first seems too soft, was rated by our riders as one of the most comfortable. Ditto for the passenger accomodations. The bike’s twin-headlight fairing may not be an aerodynamic masterpiece, but it cleaves the air effectively and leaves the rider in a relatively calm environment, although the optional lowers are much more effective as toe-trappers than as wind-blockers. The Tour Glide’s radio works well, and the sliding volume-control on the left handlebar pod was singled out by everyone as a good feature.

On the other hand, almost all of our riders commented on the Harley’s relative lack of sophistication. And while some buyers will undoubtedly seek out the Tour Glide just because it is so different from the Oriental touring bikes, all the hand-drawn pinstripes in the world don’t make up for shoddy-looking bracketry, overspray on the fairing, reluctant luggage locks and fairing-pocket edges almost sharp enough to draw blood.

Then, too, there are the saddlebags that are low on volume, especially the right one, which has to wrap around the large battery. And since the bags and trunk are crafted of fiberglass instead of plastic, everything that rests inside the luggage, from longjohns to ham sandwiches, ends up with the distinctly repulsive scent of fiberglass resin. We also had some niggling problems with the FLT. The speedometer gave up the ghost in Alabama, a floorboard rubber disappeared in Florida, the horn parted company in El Paso, and throughout the tour, the engine insisted on misting the entire right side of the bike, and the rider’s leg, with 10W-50.

Despite that rather lengthy list of complaints, though, there was never a shortage of volunteers ready to perch atop the Harley, whether it be for a quick spin around Daytona Beach or an 800-mile drone through the endlessness of Texas; and that probably says more about the bike’s touring capabilities than a simple tally of what works and what doesn’t.

HIGHWAY Tallahassee, 319 Florida, RUNS FROM north into Georgia, and almost as if on cue, red clay appears along the roadside as soon as you cross the state line. Take a few side roads and suddenly you’re bisecting thickets of dense woods, with only the occasional white cinderblock church, or perhaps an old plantation that now survives as a bed-and-breakfast inn, marking your progress. Eventually, Highway 84 comes into to view, leading to Alabama and stops in towns named Enterprise and Elba and Opp and Andalusia.

In this kind of going, where the trip constantly is interrupted by first-gear crawls through stop-sign-infested towns, Kawasaki’s Voyager XII reigns supreme. Although it’s really not that much lighter than its fully equipped competition, its marvelously low seat and easy slow-speed handling make for a very unintimidating package, even for smaller riders.

Not that the Voyager is only good for around-town riding. With a quick-revving, silky-smooth engine, a crisp-shifting transmission, and gearing that has the pistons barely moving at cruising speeds, the XII is an easy ride on the open road. Acceleration is fierce in the lower four gears, although the overdriven fifth gear means that a downshift, sometimes two, is required to zip past traffic in passing situations.

We also liked the extremely light twist needed to open the throttle, although the lack of a cruise control is almost unforgivable, even in view of the bike’s “economy-class” approach to touring. As with the Harley, the Voyager’s thumb-operated radio-volume control was appreciated, although we all felt the radio lacked sufficient decibels, especially at high speeds. And don’t worry about reduced luggage capacity on this

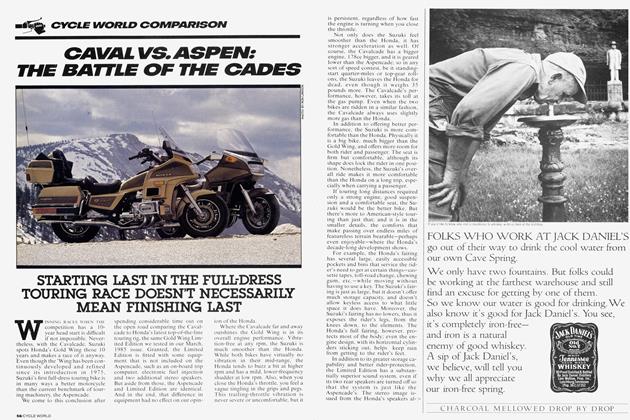

SUZUKI CAVALCADE LX

IF YOU COULD SUM UP THE PHILOSOPHY BEHIND Suzuki’s Cavalcade in two words, they might very well be “why not?” Why not build the biggest touring bike on the road? Why not give it the the largest displacement of anything in its class, and for that matter, the largest displacement of any motorcycle ever to come out of Japan? And why not use an existing motor for the basis of the touring model?

That pretty much describes the Cavalcade, at 1360cc the largest-displacement motorcycle made in Japan. And physically, it is one of the largest bikes made anywhere, with the exception of Kawasaki’s massive six-cylinder Voyager and the hulking Amazonas from Brazil.

But there’s more to the Suzuki than just sheer size. The Cavalcade is built around one of Suzuki’s most powerful engines, the one in the 1200cc Madura cruiser, so out of heredity alone, the motor can't help but be healthy. Suzuki took the Madura’s 1 165cc VFour, opened up the bore by 3mm and extended the stroke 5mm, creating an 81 mm-by-66mm, 1360cc touring powerhouse. In addition, the Madura’s sixspeed gearbox was replaced with a five-speed, and the 360-degree crankshaft was axed in favor of a 180degree crank to enhance smoothness. There also were appropriate changes in cam timing, compression ratio and carburetion, all intended to transform a snarling, quarter-mile screamer into a pleasant tourer.

While Suzuki used an existing motor as a starting point for the Cavalcade, the chassis came from a clean

sheet of paper. As you might expect, the end result is big. Its 66-inch wheelbase is the longest of these six touring bikes, and the seat height ranks among the tallest. The bike’s storage capacity is one of the greatest, and even the fairing and windscreen are the widest in the comparison test.

That same biggest-and-most philosophy is evident in the passenger accomodations. The second rider on the Cavalcade is treated to a very wide seat and a large, cushy, adjustable backrest. Ón the LX version, the passenger even has a few features that the guy in the front seat might be jealous of. With the push of a button, the passenger can inflate or deflate any one of three air cushions—two in the backrest and one in the seat. The back-seater also has a set of stereo controls and a lever that changes the angle of the floorboards.

All this is standard on the LX, the model tested here. There also is a less costly GT version, that, for $ 1 700 less, does without the luxury of the stereo, the air cushions, the cruise control and the auto-leveling air-suspension system. Then there’s the recently released LXE, the top-of-the-line model that has even more features and retails for $9299.

But with all three models, the basic idea is the same. When designing the Cavalcade, Suzuki came to the conclusion that touring riders are attracted to the biggest, plushest, most luxurious machines on the road. The fact that the Cavalcade is exactly that kind of bike is no mistake.

downsized tourer: It’s on par with that of the other Japanese bikes.

Still, the Voyager falls behind in several areas. Number one: For some reason, the Kawasaki liked to wander around. Nothing drastic, mind you, but it had a constant, straightline shuffle that always needed to be compensated for. Strangely, this trait didn't show itself in the corners, where the XII was very stable and

limited only by a relative lack of ground clearance when really heeled over. Because the weaving got worse as the trip wore on, the solution may be as simple as a new set of tires.

Number two: Nobody really liked the fairing. Mounted rather far from the rider, it has a lot of air spillover, which results in almost constant buffeting. Some riders even suggested that the fairing was a contributing factor to the bike’s meandering and the radio’s lack of volume.

Number three: The seat, while by no means a Marquis de Sade special, could use some further development. We’d suggest softer and slightly wider padding for both rider and passenger.

Number four: Several riders were annoyed by the bike's gear whine, especially when cruising at high speeds with the radio off although some riders never mentioned the noise and others thought it was no worse than the sounds emanating from the other bikes in the comparison. Kawasaki engineers are aware of the whine and claim that as miles go by, the noise subsides slightly.

Even with those teething problems, though, the Kawasaki is such a good bike that the other companies would do well to pay attention. The Voyager clearly shows that a touring motorcycle doesn't have to be extreme, either in price or size, to take on the roads of America.

INTERSTATE leans and Houston 10 BETWEEN has the NEWORpotential to be excruciatingly boring. But some days, like today. Mother Nature provides a sideshow. A nearmonsoon is safely to the rear, and the skies in the west have been washed clean, save for a few renegade storm clouds, low-flying and sooty, which serve only to frame the beauty of the setting sun. To each side, impossibly green fields slide by, and as the air cools, patches of fog pop up here and there.

The rider aboard Suzuki’s Cavalcade LX plugs another cassette into the tape deck, adjusts the cruise control to match the speed of the other bikes in the group, and slides back on the seat, mentally noting the mileage to the next fuel stop.

For interstate gas-station hopping, the Cavalcade is a tough bike to beat. With the roomiest seating position, one of the best saddles and an unstressed engine note, the Suzuki just sips down the miles.

What's surprising, however, is that the Suzuki coddles its rider despite having a fairing with some serious shortcomings. Why lowers weren't designed into this package is a mystery: Besides letting a rider’s legs get cold and wet, the open space funnels drafts at the rider’s torso. And while the wide windshield does a fairly good job of protecting from the front, a residual air-blast pushes from the rear. In fact, the fairing/windshield combo sets up such weird currents that in the rain, large droplets of water assault the rider from behind and below.

The second most commented-on aspect of the Cavalcade was its lowspeed handling. This is a big, topheavy motorcycle whose in-town behavior can make even experienced motorcyclists feel clumsy, especially after a long, tiring day on tour. Neither was our test Cavalcade’s highspeed handling or cornering anything to write home about. At really high speeds, admittedly higher than most touring riders will care to go, the bike had a nasty wobble, which we later traced to a misaligned rear wheel— not an easy problem to deal with on a shaft-drive bike that has no axle-adjustment capabilities.

Still, there are a lot of touring riders for whom the Cavalcade will be perfect, riders who revel in knocking off 200-mile interstate runs before breakfast and then look longingly at the horizon. We can’t help but wonder, though, just how good the Suzuki might be with a few specific improvements, and hope the new LXE is a step in the right direction.

HIGHWAY Mexico and IO THROUGH Arizona offers NEW blessed relief from interstate drudgery. Parting company with I-10 at Lordsburg, 70 offers sweeping, high-speed sections that skirt mountains, and just enough small towns to give a splash of local color without slowing things down too much. At Globe, a short but spectacular section of asphalt bumps and grinds its way down to the desert floor and, eventually, to Phoenix, 80 miles to the west.

In this kind of riding environment, which offers a little bit of everything, the Honda Aspencade SE-i is at home. This is a bike that devours straightline miles with ease, but is still capable of mounting a respectable attack during backroad slaloms. Helping the miles pass easily are a fairing and windshield that create a comfortable still-air pocket, no matter what the speed, and a cruise control so precise in operation that it rivals those found in luxury automobiles. The Honda’s cruise system is certainly a step ahead of the Suzuki and Yamaha units, not to mention the Harley’s thumbwheel set screw.

We’d like to see a few things changed, though. Hand protection from the fairing could be improved; perhaps something as simple as mirror relocation would do the trick. The otherwise impeccable four-speaker sound system would be that much better with a volume control on the handlebar, a la Harley and Kawasaki. And while its flat-Four engine has many desirable traits, it seems a little uninspired after riding the Venture and Voyager. Our staff curmudgeons shot down the digital instrumentation, and almost everyone thought the trip computer was interesting, but unnecessary.

On a more serious note, our SE-i’s troublesome suspension-leveling system let us down again: By the end of the trip, the rear shocks had to be aired up every few minutes. The problem appears to be a faulty valve and will be fixed under warranty— again—but it’s a bother nonetheless.

The sacked-out suspension didn’t stop anyone from being thoroughly impressed with the Wing’s touring prowess, though. Two words kept cropping up: “balanced” and “refined.” As one rider neatly put it, “There is very little to criticize about the Honda. What it does well, it does better than anything else; what it does poorly, it still does quite well.”

THEN IT CAME TIME TO LOOK 1 i back over a 5600-mile, ■ H nine-state transcontinental tour, sort through all the notes, weigh all the riders’ comments, computer-crunch the numbers and come up with this comparison test’s winner, there was no need for smoke-filled rooms, impassioned debates or near-fisticuffs.

HONDA ASPENCADE SE-i

fOR ALL PRACTICAL PURPOSES. HONDA’S TOP-OF-

the-line Gold Wing Aspencade SE-i merely is last year’s Limited Edition model painted in different colors. But for many people, that’s just what the touring doctor ordered. As far as they're concerned, why change a good thing? And as a motorcycle that’s in its 12th year of an extremely successful existence, the big Honda tourer most definitely is a Good Thing.

At the heart of the SE-i is, essentially, the same liquid-cooled, sohc, shaft-drive, horizontally opposed four-cylinder engine that has powered the Gold Wing since the bike’s inception in 1975. The motor has, of course, been refined, strengthened and upsized over the years, beginning life as a 1000, growing first to an 1 100 in 1980, then to a 1200 in 1984. And as the years have rolled by, the merits of this ultra-smooth, low-cg engine as a touring powerplant have proven themselves to thousands upon thousands of riders all across the country.

Like the Limited Edition before it, the SE-i is electronically fuel-injected (all other Gold Wing models use carburetors). And aside from providing more precise fuel metering than carburetors over a wider range of conditions, the injection system easily measures the rate of fuel-flow, thus allowing the use of an on-board trip computer that calculates various rates of fuel consumption. The computer keeps the rider informed of, among other things, current and trip-average fuel mileage, projected number of miles possible with the

amount of fuel remaining in the 5.8-gallon gas tank, and number of miles left to his destination. There’s also an LCD map of North America on the computer’s display that is divided into five time zones; the rider can find the current time anywhere on the continent by merely pushing the clock button until the desired time zone is flashing.

And making continent-crossing that much easier is an electronic cruise control, which allows hands-off cruising at highway speeds. And the SE-i also has an on-board air-compressor system that can regulate the amount of air in either the fork or the dual rear shocks, or automatically level the bike at both ends with the flick of a lever on the handlebar control pod.

There’s also a pretty sophisticated sound system on the SE-i. An extremely compact, Panasonic-built AM/ FM tuner with cassette deck fits neatly and unobtrusively into the dash panel, just below the instrument cluster (which consists almost exclusively of LCD readouts). A four-speaker system (two in the fairing, two more flanking the headrest on the tour trunk) is controlled by a little “joystick” on the trip-computer console atop the dummy gas tank. A CB radio is optional on the SE-i, but an adjustable handlebar, a three-position fore-and-aft-adjustable seat, and an adjustable-height windshield are standard.

At almost $10,000, all this doesn’t come cheaply. But as the sales success of the Gold Wing series has shown, touring riders don’t mind paying the price for a Good Thing.

Simply put, the Honda wins.

Two questions were asked of our riders. The first was, “Which bike would you buy, keeping in mind things like price and personal preferences?” Two riders picked the Yamaha on the strength of its dynamo of an engine. Another two voted for the Kawasaki, citing its low price. The remaining four riders fell in line behind the Honda, picking it for its all-

around competence in spite of its high price. One of the Honda backers even commented that if the SE-i’s $10,298 asking price was too high, the standard Wing, at $6498, and the Interstate model, at $8298, were available. Both have less opulence than the SE-i, sure, but almost all of the basics that make the Honda so good are still there.

The next question asked the riders to choose the best touring bike in America, regardless of price. This time the tally was even more dramatic: Honda 7, Yamaha 1.

That doesn’t mean the Honda will be right for you; and without doubt, any one of these bikes is capable of delivering mile after mile of enjoyable touring. But our idea of touring means being able to take on any kind of road, from the desert-conquering interstates of the Southwest, to the twist-filled works of art that cross the Continental Divide, to the lush highways that lope across the South. For that kind of riding, there’s none better than Honda’s Aspencade SE-i. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue