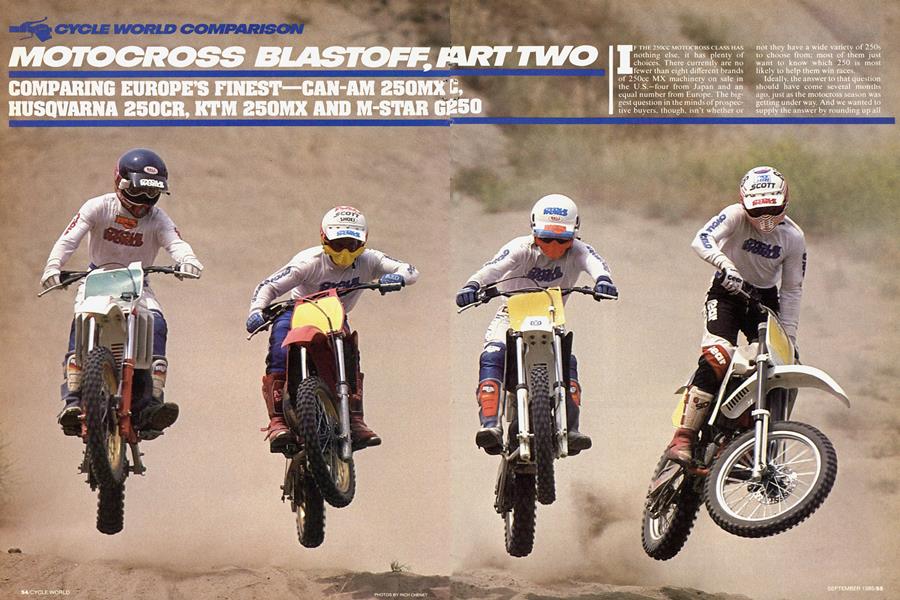

MOTOCROSS BLASTOFF,PART TWO

CYCLE WORLD COMPARISON

COMPARING EUROPE'S FINEST—CAN-AM 250MX LC, HUSQVARNA 250CR,KTM 250MX AND M-STAR GM250

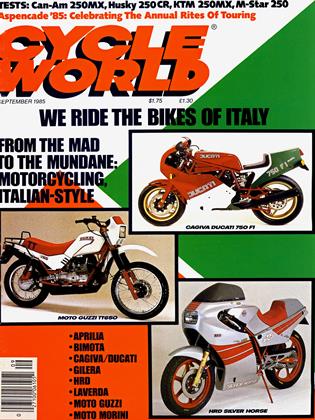

IF THE 250CC MOTOCROSS CLASS HAS nothing else, it has plenty of choices. There currently are no fewer than eight different brands of 250cc MX machinery on sale in the U.S.—four from Japan and an equal number from Europe.. The big-gest question in the minds of prospective buyers, though, isn't whether or

not they have a wide variety of 250s to choose from: most of them just want to know which 250 is most Iikdy to help them win racts

ideaLly, the answer to that question should have come several months ago, just as the motocross season was getting under way. And we wanted to supply the answer by rounding up all of the 250-class machinery and having one whale of a shootout. But because not all of the European 250s were available back then, such a test was impossible. Instead, we had to settle for answering just half of the question by comparing only the four Japanese 250s (April, 1985 issue). Our game plan was to compare the four European 250s as soon as they all became available, then pit the winner of that contest against the winner of theali-Japan 250 shootout.

Well, all of the European 250s have finally made it to these shores, so we present Part Two of the Great American 250 Shootout. The combatants for this four-way warfare are; Can-Am’s 250MX LC; Husqvarna's 250CR; KTM’s 250MX; and the GM250 from M-Star (formerly Maico). At the end of it all we’ll first choose a European winner, and then find the overall 250-class champion by locking that bike in head-to-head competition against the winner of the Japanese segment-which, in case you didn't already know, was Kawasaki's powerhouse KX250.

To make the final results as meaningful as possible to riders everywhere, we used several different motocross tracks. We also employed a wide range of riders, from Pro to Novice, young to old, light to heavy.

All four of these bikes make good power, but their powerbands are much different from one another. The Can-Am produces the smoothest, most progressive power over a

broad rev range, and our less-experienced test riders liked that easy-touse power; most of the Pro-level riders, however, felt the powerband was better-suited to enduro riding than to motocross. Keeping the Can-Am’s

rear tire driving without excessive wheelspin is easy, but using the clutch to get a burst out of a tight turn doesn't work. The heavy-flywheeled engine revs comparatively slowly, and clutching just slows the process.

KTM’s idea of a proper 250cc motocross engine is one that makes almost no low-end power, hits violently as the revs reach the midrange, and then flattens out at higher rpm. So the only way to keep the KTM in its powerband is to ride it like a pipey—but very strong125.

The Husky’s powerband is wider than that of the KTM, but it’s not without fault, either. There’s an annoying hesitation right oiTofidle that can be extremely bothersome when exiting a tight turn. After that initial

stumble, the power builds smoothly and fairly quickly, ending in a decent top-end rush.

If it had run more cleanly at low rpm, the Husky just might have had our favorite powerband. But our attempts to clean up the low-speed stumble proved fruitless because of— in our opinion, at least—the lack ofan idle-adjustment screw. And the flatslide Mikuni carburetor can’t be fitted with one. either.

Many riders felt that the Husky was less powerful than the other bikes, but drag races between all four disproved their feelings. All of the bikes were closely matched, and a rider’s start-line expertise proved more important than the brand of bike he was riding. Rick Maki, for example, usually jumped ahead no matter which bike he was riding.

KTM 250MX

N ENGINE WITH A 7mm LONGER STROKE AND A

3.5mm smaller bore heads the list of new for KTM’s '85 250MX. Lengthening the stroke meant the ports could be taller (and thus larger) without making the port timing any more radical. The cylinder is no longer reborable, for the cast-iron cylinder sleeve is gone, replaced by an aluminum bore surface coated with Nikasil, an extremely hard, electronically applied nickel-silicon-carbide treatment. Closer piston-to-cylinder clearances and better heat-dissipation are possible with this type of cylinder, both of which mean more horsepower.

Other changes to the engine benefit its longevity. The cases have been strengthened around the main bearings, the kickstarter gears are stronger, and transmission breather hose is larger in diameter.

A chrome-moly steel frame much like the one on last year’s 250 is still used, but there is one small change: The steering angle is half of a degree steeper at 26.5 degrees. A White Power single shock mounts 1.5 inches lower in the chassis this year, and the aluminum rear-suspension linkage has been changed for a flatter progression curve. The pivots for the linkage, as well as those for the aluminum swingarm, have grease fittings to ease maintenance.

A White Power fork with 54mm-diameter upper tubes and 40mm lowers promises excellent stability and positive steering. The fork doesn't have any external adjustments, but it can be fine-tuned after disassembly. A floating, stainless-steel disc-brake rotor bolts to a tiny, lightweight front hub. Rear braking is handled by a dual-leading-shoe drum brake.

M-Star GM250

TWO YEARS AGO, WHEN THE M-STAR WAS

still a Maico the 250 was given a completely new engine that included reed-valve induction and geared primary drive. Improvements to the engine for '85 amount to new cylinder porting and a redesigned pipe. A 38mm Bing carburetor supplies the fuel to the motor, and a Motoplat ignition furnishes the spark.

For years, Maico’s 27-degree steering-head angle was considered quite steep, but now the rest of the industry has made steep fork angles the new standard. The M-Star’s frame uses basically the same design as that of Maicos of the past, but with larger-diameter

tubing for increased strength.

In the rear, suspension is through an Ohlins single shock working on a swingarm and linkage components made of aluminum. A knob on the shock reservoir adjusts the compression damping, and a knob on the bottom of the shock body adjusts the rebound damping. The M-Star-built front fork has 40mm stanchions and new-for-’85 damper rods.

Braking is much-improved for 1985 due to a 9.6inch disc up front and a 6.3-inch drum at the rear. In the plastic department, there is a new. 2.7-gallon gas tank that carries the fuel lower on the frame, and side numberplates that slim the bike through its middle.

Our favorite powerband was the M-Star's. Engine power, or lack of it, may have been a problem wath 250 Maicos in years past, but not any more. Although still a little pipey, the engine has a strong surge of power that starts in the lower end of the middle-rpm region and keeps building all the way into the upper-rpm range. Keeping the M-Star in its powerband is fairly easy, too, thanks to its seemingly perfect gear ratios and smooth-shifting gearbox.

In fact, the M-Star’s gearbox outshines the other five-speed transmissions in shifting ease, gear ratios and lack of missed shifts. The Husky is a close second, and both the Can-Am

and KTM need help. The Can-Am's transmission has reasonably spaced ratios, but its lack of feel w hen shifting caused some rider complaints— and a bunch of missed shifts. The KTM’s gearbox is best described as awful. There is a huge ratio-jump between second and third, the shift lever moves stiffly, and the transmission can’t be shifted unless the throttle is shut off completely. Not surprisingly, missed shifts on the KTM were all too common an occurence.

Another strong point of the M-Star is its suspension. The fork is the smoothest of the bunch, with excellent damping and the correct spring rate. The Ohlins-equipped rear suspension also works smoothly and comfortably, even through gnarly

whoops and on landings from tall drop-offs, and there's no detectable shock fade during a 30-minute moto.

Husky’s 250CR has the secondbest suspension. The Ohlins shock performs fairly well over medium and small bumps, but'the rear end starts getting loose when the speed rises in deep whoops. And there is an annoying kick toward the end of a long run of whoops, which is especially noticeable when entering a whooped corner with the brakes applied hard. Experimenting with the external shock adjustments helped a little but didn’t completely eliminate the kick. The Husky’s front fork also drew complaints about its harshness on squareedged bumps and its tendency to bottom during jump landings.

Husqvarna 250CR

FOR new ’85, porting HUSKY'S (including 250CC MOTOCROSS two boost ENGINE ports that HAS straddle the main exhaust port), a new pipe and a hat-slide Mikuni carburetor. But even though these changes increase the 250CR’s peak power and w iden its powerband, the real news for '85 is the new single-shock chassis.

Designed around a single, large-diameter backbone tube that curves from the steering head back to the swingarm pivot, the frame is simple and yet seems strong. And the new' Husky incorporates a subframe that can be removed for maintenance of the Ohlins dual-clicker shock. The steering head now has an unusually steep (fora Husqvarna), 27-degree angle, and the triple-clamps have more offset to further shorten the front-wheel trail and quicken the steering. The massive swingarm and its suspension-linkage arms all are aluminum and pivot in uncaged needle bearings. An aluminum rear-brake pedal is new. featuring a bearing at its pivot and a saw tooth boot-pad made of steel. The 250CR's front fork is still made by Husqvarna, and still allows no external adjustments other than air pressure and oil level/weight.

Braking on the CR is through a 6.3-inch rear drum and an hydraulic front disc with a large, cast-iron rotor. The handlebar-mounted master-cylinder has been improved since our last Husky test (500XC, May, 1985) and now has a freeplay adjuster and a return spring to prevent the lever from sticking.

Also improved for '85 is the width of the bike in the area just above the footpegs. The single-shock chassis has allowed the exhaust system and the side numberplates to be tucked in, and the low-slung gas tank has a nice, narrow shape.

The K I M's suspension got mixed reviews from our test riders. One rider thought the fork was excellent, several rated it good, and one felt it was poor. This wide range of opinions stems from the fact that the White Power fork is very sensitive to rider weight and style, and so requires quite a bit of dialing-in to be right for anv individual rider. Tikewise, the rear suspension drew mixed feelings, although in this case the riders rated the performance anywhere between poor to good, but no higher.

That's a higher rating than the

O C.

Can-Am received, for none of the testers felt that its suspension behavior was better than just fair. The Marzocchi fork is too soft on the big stuff and yet beats the rider on the little bumps. The White Power shock also is too soft for motocross, even when all of its adjustments are at their highest positions. So the rear of the bike bottoms on just about every jump landing, even small ones. Making matters worse is the location of both the shock body and the remote reservoir. Not only are they difficult to reach for adjustment, but they don't get hit w ith much cooling air; as a result, the damping fades almost completely in only a couple of fast laps on a rough track.

Riding the Can-Am around a corner can pose a few' problems, as well. The bike wants to turn, but its ultrasoft suspension and long wheelbase work against it. Trying to bend a bike with a 61-inch wheelbase around most motocross turns can be a chore.

On the other hand. Maicos are famous for their quick, precise turning in the corners, and the new M-Star seems likely to continue that reputation. All of our riders felt faster and more comfortable through all sorts of turns on the M-Star. mostly because the bike practically refuses to do anything wrong w hen cornering.

Our second-favorite turner was the Husky, which was hampered only by its marginal shock compliance on the rougher corners. The 250CR railed around berms and sliced through all but the most slippery of turns with an ease not associated with Huskys of years past. Only the slickest turns found the front tire trying to skate some, but that was probably due more to suspension compliance than it was to any flaw in the Husky’s steering geometry. We liked the KTM's steering a lot, too, for it reacted instantly to any movement of the handlebar. The huge White Power fork doesn't flex, so it was easy to oversteer the bike for a few laps until we got used to that rigidity. Nevertheless, most riders gave the KTM’s overall turning ability only a “good” rating due to the rather confused suspension and the bike's annoying tendency to climb up berms.

CAN-AM 250MX LC

$2803

HUSQVARNA 250CR

$2895.

There were no rave reviews for the KTM’s brakes, either. The front disc brake required a lot of muscle and— for some unknown reason—constant air bleeding, and the dual-leadingshoe rear brake had very little feel

and locks up too easily. Complaints about the Can-Am’s brakes were predominant. too. In an age when just about all motocross bikes have disc front brakes, Can-Am has updated its old single-leading-shoe front brake with dual-leading shoes. But there’s no turning back when it comes to brakes: anyone who has used a good disc front brake is usually unhappy with a drum. The Can-Am’s is no exception; it's less powerful than the discs it has to compete with, and it fades badly when hot. The weak rear brake compounds the problem.

M-STAR GM250

$2980

Husqvarna did a better job of engineering its brakes. The front requires more lever pull than a Japanese stopper but has good feel and a progressive action. The rear brake also works

fairly well thanks to a new brake pedal. But the M-Star gets the trophy for having the best brakes of this foursome. The front disc has good feel, progressive action and excellent stopping power. The rear brake also rates above the others in feel, power and controllability.

In terms of overall comfort, the MStar and Husky again scored high

points. Both bikes seemed to fit a wide variety of riders better than the other bikes did, with the KTM ranked third and the Can-Am again being the least favorable. The Husky and M-Star also have best seats; the KTM’s seat is as hard as a rock, and the Can-Am's seat is both too wide and too soft, a combination that makes moving about difficult. >

Can-Am 250MX LC

IF familiar, THE ENGINE that’s IN because THE 250MX it is the LC same LOOKS basic VAGUELY Rotaxbuilt powerplant that has been used in Can-Am motorcycles since they came into being more than 12 years ago. In 1983, the switch was made to liquidcooling, and this year the engine has new porting, a redesigned pipe, and a variable-height exhaust port intended to boost peak horsepower while also widening the powerband. This exhaust-control mechanism uses variations in exhaust pressure to raise and lower a flat slide just behind the exhaust port, which changes the effective height of the port.

As always, the 250 uses Rotax’s special brand of rotary-valve induction. The intake tract is unusually long, beginning at the 34mm Mikuni carburetor that sits low and to the left-rear of the engine, and ending just behind the rotary-valve disc attached to the left end of the crankshaft.

Chassis-wise, the frame on the 250MX LC uses beefy, large-diameter tubes that ought to make the main frame exceptionally strong and durable. The rear subframe unbolts quickly for easier access to a White Power shock that’s buried between the airbox’s dual inlet hoses. That single shock is the key component in Can-Am’s Quad Link rear suspension, which uses a nicely made aluminum swingarm.

Up front, the suspension chores are handled by a not-particularly sophisticated Marzocchi fork that uses 40mm stanchions. So, too, is the front-wheel design rather dated by current standards; it uses a dualleading-shoe drum brake and wheel spokes that must make a sharp bend as they exit the hubs. The Can-Am also is unusually long and tall (6 1-inch wheelbase and 39.5-inch-high seat) for a 250cc motocrosser.

Really, about the only area in which the M-Star did not do exceptionally well was reliability: In the middle of the test, a main bearing failed and locked the engine solid. Trouble with the other bikes was less severe. The Husky's chain stretched continually and derailed twice during the test; the Can-Am’s radiator required refilling twice a day due to water loss past the radiator cap. But the KTM, amazingly, suffered no problems, despite having gone through 10 races and a full test before our comparison even began.

But reliability alone is not enough to compensate for the KTM’s shortcomings in other areas, and that’s why it doesn't win the shootout. Likewise, the Can-Am falls short in the final line-up. The Husky came close, but in the end. the winner, the one bike that stood alone above its European competition, was the MStar. It did almost everything as well as or better than the others, finishing last only in reliability.

We chose the M-Star as the winner on a purely subjective basis, based on our emotional feelings about all four

of the bikes. But we then voted on the machines in a number of important categories just to see if our conclusion would hold up to the results of a points tally.

It did. The M-Star got five firstplace votes, four of them from Prolevel riders. The Husky won four firsts and a bunch of seconds. The KTM got just one first-place vote, the Can-Am none.

So mathematically as well as analytically, the M-Star is the winner. It’s the best 250 motocross machine Europe has to offer.

KAWASAKI vs. M-STAR: THE FINAL CONFLICT

F INALLY. AFTER SIX MONTHS. TWO SEPARATE TESTS and thousands of laps around a variety of mo tocross tracks, it all comes down to this: Which is the best 250 of all? Is it the M-Star GM250 that just won the European comparison, or the Kaw asaki KX2SO that took our Japanese test?

To solve that riddle, we revived the very same KX250 we had used in our Japanese 250 test and put it out on the track with the M-Star. The KX had run a half-dozen motocross races since that April comparison, along with a 1 20-mile desert enduro and a couple of trail rides. So it needed a bit of reconditioning to get back in fighting shape. The engine was still running perfectly, so it was left alone, but a new chain and sprockets were in order. And the Metzeler tires were replaced with OEM Bridgestones just to make the comparison as fair as possible. We also used the same crew of test riders that had participated in the European shootout, nine of whom had also been involved in the Japanese comparison.

The results were overwhelmingly in favor of the Kawasaki. The KX250 was faster than the M-Star and had power that hit harder and more suddenly (a big favorite among the Pro-level riders), yet it was easier to ride. That’s because the Kawasaki was more agile in most aspects of its handling, with controls that worked more easily, suspension that was plusher, and brakes that were easier to regulate. The M-Star’s fabled steering ranked a bit higher than the Kawasaki’s, but not by much: the KX250 is quite a turner in its own right. Not only that, most of the riders pointed out that having a much larger dealer network behind it can be a distinct advantage for the Kawasaki.

It’s no wonder, then, that nine out of the 10 riders said that the Kawasaki was the 250 motocross bike they’d most like to own. The one rider who preferred the M-Star, incidentally, was a Pro who has spent quite a lot of time racing Maicos in recent years, and he admitted a certain favoritism based on his experience with those German machines. But for everyone else involved with the test, there was only one conclusion: Kawasaki rules in the 250 class. E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

September 1985 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

September 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupAikido: Pre-Accident Preparation

September 1985 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

September 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

September 1985 By Alan Cathcart