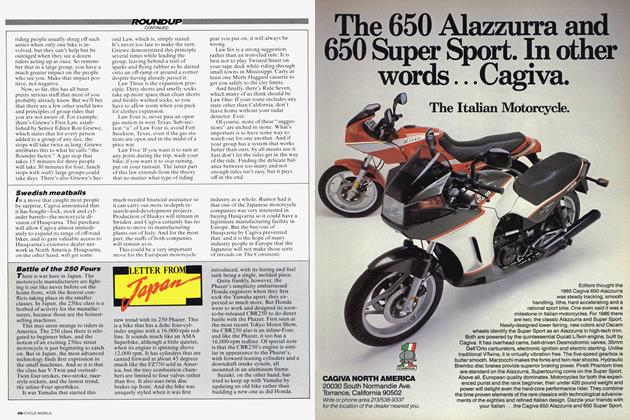

KAWASAKI 250 NINJA

CYCLE WORLD TEST

CHAMPION OF SPORT-BIKING’S SMALLEST CLASS

THERE'S A DISTINCT ADVANtage to being the only competitor in your class: It’s almost impossible to lose. The rules are only what you make them, the standards only the ones you set. You’re automatically the best, by default if not by merit.

That’s how it is with Kawasaki’s newest sportbike, the 250 Ninja. There are no other 250cc sport machines for sale in this country, and there hasn’t been since long before the term “sportbike” became the accepted description for any motorcycle with a penchant for unraveling twisty roads. So with no competition, the 250 Ninja is the best 250-class sportbike sold in the U.S., bar none.

When there are no other motorcycles to use as a point of reference, though, it’s hard to know what to expect from any bike. You have to base your expectations solely on appearance. And in the case of the littlest Ninja, the bike is not quite what it appears to be. Once you observe its dohc, liquid-cooled, four-stroke, two-cylinder engine, complete with 14,000-rpm redline; its racing-type, three-spoke cast wheels; its disc brakes front and rear; its integral quarter-fairing molded into the fuel tank; its jet-black finish and hightech bodywork; once you see all that, logic tells you that you’re looking at a hard-edged street racer, one with an quick-revving engine that suddenly bursts into a pocket of horsepower somewhere in the high-rev zone.

Nothing could be farther from the truth. For one thing, the Ninja revs rather slowly. The engine has so much flywheel effect that it sometimes feels more like an ultra-highrevving big Single than it does a Twin. What’s more, it has a powerband that you’d expect on a commuter bike or maybe even a trials motorcycle, but not a street-going roadracer. The power comes on smoothly and gradually from idle to redline, with never a surge or the sudden arrival of a gang of horsepower. The engine just revs higher and higher, picking up power in a linear fashion along the way, with peak horsepower produced somewhere around 11,000 rpm. Consequently,

you can shift a little early or a little late without dire consequences; and that, too, is not typical for a smallbore sportbike.

But while the Ninja produces predictable, easy-to-use power, it doesn’t generate an exceptional amount of it. Once again, the bike looks like it ought to be the fastest thing this side of a Yamaha TZ250, but its performance is, well, good but not spectacular for a 250. Admittedly, it will make quick work of the only other 250cc streetbike on the U.S. market, Honda’s 250 Rebel econo-chopper; but the Honda is a bike noted more for its stellar performance in the showroom than on the street. And don’t forget that since there are no other 250cc sportbikes on the streets, nobody knows how fast the Ninja is supposed to be.

Besides, there’s nothing magical, or even unusual, about the 250 Ninja’s engine. The eight-valve Twin displaces 248cc, has a gear-driven counterbalancer just ahead of the crankshaft, and is claimed to produce about 38 horsepower. And its ability to rev to astronomical limits is as much due to its exceptionally short stroke (41.2mm) than to any particular tuning trick. The engine is very compact, even for a 250 Twin. This was accomplished through some intelligent engineering, such as plac-

ing the cam chain on the right side of the engine rather than between the cylinders, and by using very short rocker arms so the dual overhead cams could be placed closer together.

Actually, the 250 Ninja is a littlechanged version of a domestic Japanese model. The biggest difference between the U.S. model and its Japanese counterpart is in the jetting of the 32mm Keihin carbs—a change made to allow the EPA to smile on the Ninja’s exhaust emissions. That cost some power, though, as the Japanese model is claimed to have about five more horsepower.

But even if the 250’s horsepower output won’t make headlines, its handling just might. Going around corners, in fact, is one area of performance where the Ninja definitely lives up to all expectations. There’s practically no corner too sharp, no decreasing-radius turn too tricky for the bike to handle with ease. Much of that agility is due to the bike’s light (334 pounds dry) weight, but most of it is a direct result of an excellent chassis and good tires. The little Ninja has a lot of cornering clearance, but a reasonably aggressive rider can still drag a bit of hardware on the pavement fairly easily simply because the bike is so unintimidating and easy to throw around.

Contributing to the bike’s exceptionally light, responsive feel are its 16-inch wheels front and rear, and its short, 56-inch wheelbase. Despite the quickness those elements lend to the handling, however, the 250 has sufficient stability in its steering geometry to be rock-steady at higher speeds— yet another of the little Ninja’s many surprises.

Really, the bike’s only chassis shortfall is not in its handling but in its ride. Bumps, potholes and railroad crossings all deliver kidney-jarring blows that the Ninja’s single-shock rear suspension does very little to soften. Oddly, the suspension seems neither too stiff nor too soft—for riders weighing under 150 pounds, at least—but the rear end doesn’t ade-

quately respond to sudden impacts. The fork is more responsive, although it does dive rather radically when the Ninja’s effective front and rear disc brakes are called into action.

The suspension gets no help from the seat, which does little more than keep the rider from sitting on the frame rails. The rider’s portion of the seat looks like something straight off a racebike, as does the cleverly disguised passenger section that looks more like a tail-section cowling on a bike without a passenger seat. After a short time in either seat, it becomes quite apparent that both were a project assigned to a styling team, rather than to the boys in the ergonomics department.

Not that any other aspect of the Ninja’s ergonomics was designed for long-range riding, either. The seating position is compact enough to identify the bike’s target buyer as someone quite short and fairly thin. The footpegs are high, the seat is low, the handlebars are flat; and for anyone larger than the average jockey, the mirrors offer little more than a stereo view of a rider’s own armpits. In all fairness, the Ninja is, after all, only a 250, but most riders will constantly be reminded of that fact any time they’re in the bike’s saddle.

Then there’s the 250 Ninja’s retail price, which, at $2299, is as stiff as its seat. For that kind of money you can buy quite a few larger machines, including Yamaha’s new Radian—a 600cc, four-cylinder, full-size motorcycle. And the closest thing to the Ninja, Honda’s 250 Rebel, is about $800 cheaper.

That’s okay, of course, because for the present, the rules for 250cc sportbikes are whatever Kawasaki says they are. If the little Ninja has a high price, a hard seat and harsh suspension, then that’s the way 250cc sportbikes are. Likewise, since the Ninja has outrageously good handling, an exceptionally wide powerband and racer-like styling, 250cc sportbikes in the future will be measured by those standards, too.

But that’s only if there are any 250cc sportbikes in the future. This country hasn’t shown much fondness for small streetbikes in recent years, and only time will tell if the 250 Ninja will fade into obscurity, or if it will spur the industry to offer more sporting 250s. If others do follow, though, one thing is certain: In the beginning, at least, they’ll have to play by the rules that Kawasaki has just written.

KAWASAKI 250 NINJA

$2299

View Full Issue

View Full Issue