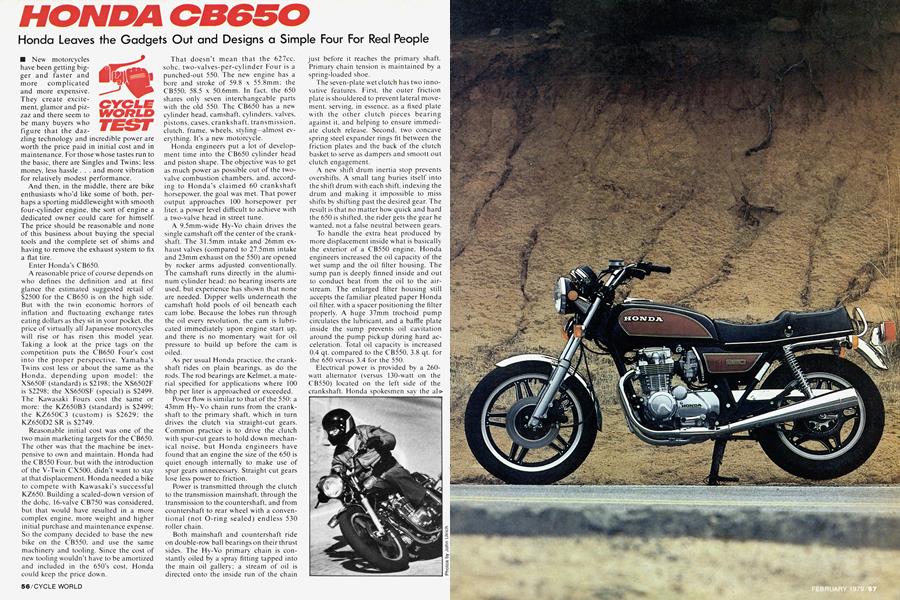

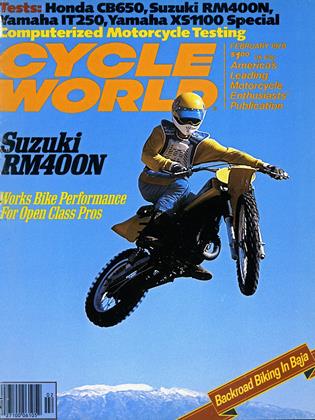

HONDA CB650

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Honda Leaves the Gadgets Out and Designs a Simple Four For Real People

New motorcycles have been getting bigger and faster and more complicated and more expensive. They create excitement, glamor and pizzaz and there seem to be many buyers who figure that the dazzling technology and incredible power are worth the price paid in initial cost and in maintenance. For those whose tastes run to the basic, there are Singles and Twins; less money, less hassle . . . and more vibration for relatively modest performance.

And then, in the middle, there are bike enthusiasts who’d like some of both, perhaps a sporting middleweight with smooth four-cylinder engine, the sort of engine a dedicated owner could care for himself. The price should be reasonable and none of this business about buying the special tools and the complete set of shims and having to remove the exhaust system to fix a flat tire.

Enter Honda’s CB650.

A reasonable price of course depends on who defines the definition and at first glance the estimated suggested retail of $2500 for the CB650 is on the high side. But with the twin economic horrors of inflation and fluctuating exchange rates eating dollars as they sit in your pocket, the price of virtually all Japanese motorcycles will rise or has risen this model year. Taking a look at the price tags on the competition puts the CB650 Four’s cost into the proper perspective. Yamaha’s Twins cost less or about the same as the Honda, depending upon model: the XS650F (standard) is $2198; the XS6502F is $2298; the XS650SF (special) is $2499. The Kawasaki Fours cost the same or more: the KZ650B3 (standard) is $2499; the KZ650C3 (custom) is $2629; the KZ650D2 SR is $2749.

Reasonable initial cost was one of the two main marketing targets for the CB650. The other was that the machine be inexpensive to own and maintain. Honda had the CB550 Four, but with the introduction of the V-Twin CX500. didn’t want to stay at that displacement. Honda needed a bike to compete with Kawasaki’s successful KZ650. Building a scaled-down version of the dohc, 16-valve CB750 was considered, but that would have resulted in a more complex engine, more weight and higher initial purchase and maintenance expense. So the company decided to base the new bike on the CB550, and use the same machinery and tooling. Since the cost of new tooling wouldn't have to be amortized and included in the 650’s cost. Honda could keep the price down.

That doesn't mean that the 627cc. sohc. two-valves-per-cylinder Four is a punched-out 550. The new engine has a bore and stroke of 59.8 x 55.8mm; the CB550. 58.5 x 50.6mm. In fact, the 650 shares only seven interchangeable parts with the old 550. The CB650 has a new cylinder head, camshaft, cylinders, valves, pistons, cases, crankshaft, transmission, clutch, frame, wheels, styling—almost everything. It’s a new' motorcycle.

Honda engineers put a lot of development time into the CB650 cylinder head and piston shape. The objective was to get as much power as possible out of the twovalve combustion chambers, and. according to Honda’s claimed 60 crankshaft horsepower, the goal was met. That power output approaches 100 horsepower per liter, a power level difficult to achieve with a two-valve head in street tune.

A 9.5mm-w'ide Hy-Vo chain drives the single camshaft off the center of the crankshaft. The 31.5mm intake and 26mm exhaust valves (compared to 27.5mm intake and 23mm exhaust on the 550) are opened by rocker arms adjusted conventionally. The camshaft runs directly in the aluminum cylinder head; no bearing inserts are used, but experience has shown that none are needed. Dipper wells underneath the camshaft hold pools of oil beneath each cam lobe. Because the lobes run through the oil every revolution, the cam is lubricated immediately upon engine start up, and there is no momentary wait for oil pressure to build up before the cam is oiled.

As per usual Honda practice, the crankshaft rides on plain bearings, as do the rods. The rod bearings are Keimet, a material specified for applications where 100 bhp per liter is approached or exceeded.

Power flow is similar to that of the 550: a 43mm Hy-Vo chain runs from the crankshaft to the primary shaft, which in turn drives the clutch via straight-cut gears. Common practice is to drive the clutch with spur-cut gears to hold down mechanical noise, but Honda engineers have found that an engine the size of the 650 is quiet enough internally to make use of spur gears unnecessary. Straight cut gears lose less power to friction.

Power is transmitted through the clutch to the transmission mainshaft, through the transmission to the countershaft, and from countershaft to rear wheel with a conventional (not O-ring sealed) endless 530 roller chain.

Both mainshaft and countershaft ride on double-row ball bearings on their thrust sides. The Hy-Vo primary chain is constantly oiled by a spray fitting tapped into the main oil gallery; a stream of oil is directed onto the inside run of the chain

just before it reaches the primary shaft. Primary chain tension is maintained by a spring-loaded shoe.

The seven-plate wet clutch has two innovative features. First, the outer friction plate is shouldered to prevent lateral movement. serving, in essence, as a fixed plate with the other clutch pieces bearing against it. and helping to ensure immediate clutch release. Second, two concave spring steel expander rings fit between the friction plates and the back of the clutch basket to serve as dampers and smoott out clutch engagement.

A new' shift drum inertia stop prevents overshifts. A small tang buries itself into the shift drum with each shift, indexing the drum and making it impossible to miss shifts by shifting past the desired gear. The result is that no matter how quick and hard the 650 is shifted, the rider gets the gear he wanted, not a false neutral between gears.

To handle the extra heat produced by more displacement inside what is basically the exterior of a CB550 engine, Honda engineers increased the oil capacity of the wet sump and the oil filter housing. The sump pan is deeply finned inside and out to conduct heat from the oil to the airstream. The enlarged filter housing still accepts the familiar pleated paper Honda oil filter, with a spacer positioning the filter properly. A huge 37mm trochoid pump circulates the lubricant, and a baffle plate inside the sump prevents oil cavitation around the pump pickup during hard acceleration. Total oil capacity is increased 0.4 qt. compared to the CB550. 3.8 qt. for the 650 versus 3.4 for the 550.

Electrical power is provided by a 260watt alternator (versus 130-watt on the CB550) located on the left side of the crankshaft. Honda spokesmen say the al-> lenuiloi produces powei from idle and utilizes a solid state regulator alternator assembk I xtra metal was added to the rear of the alternator to increase flywheel efleet But in spue of the added meat on the alternator, the t B650 is only about one meh wider than the i B55Ú 1 hat's because the alternator itself is recessed and tits over and around the outboard main bearing and oil seal Thus the larger ulternatoi does not significantly reduce cornering vie,m»nce of the 650, relative to the 550.

Honda is so confident of the high out out alternator's abilitx to keep the 12 ampere hour batten charged that no kiek sia« :e. ¡s rated to the 650 Along w uh other small touches like lightweight east alloy header clamps, the deletion of the kick 'Ur.et «‘.rade .: possible foi the i B650 engine to weigh four pounds less than the CB550 engine, 154 lb. versus I5S lb., dry.

A pointless, inductive electronic ignition system on the right side of the crankshaft sparks the 650 and requires no regular maintenance,

l arhureiion is handled by four 26mm slide-throttle Keihins: one accelerator pump mounted on the number two carb abo feeds the other three. The accelerator pump eliminates any otl-idle hesitation which might otherwise occur due to lean slow-speed jetting required to pass emissions certification. Many Honda models are fitted with constant velocity, vacuumpiston. butterTlx-throttle carbs these days m the name of good mileage and throttle response and less pressure at the twist grip (to avoid a sore arm. wrist or shoulder during long rides). One reason the C BöSO doesn’t have C A curbs is probably because a bank of four wouldn't lit in the available space, where the narrower slide throttle carbs lit line. Ik* that as it may, the ( B650\ carburetors work well, deliver good mileage and do not require excessive twist grip pressure, a tact Honda representatives say is due to design work on the bell crank assembly which links all four curbs to the push/pull throttle cables.

I he exhaust system is 4-into-2 with no balancer tube or power chamber. Mufflers are upswept and well tucked in for ground clearance.

fhe new 650's frame is similar to the old 550 frame, but there arc significant differences. I he 650 has 27.5 degrees of rake, compared to the 550’s 26 degrees. Both have 4 I m of trail. \v in the ease of the 550. it is possible to remove the 65()'s top end without pulling the engine out of the frame. But a new feature is the bolt-on right frame rail the downtuhe unbolts for easv engine removal.

W heelbase and suspension different as welf I he 650 has a 56.3 in wheelbase. lot\ge\' \Vu\v\ Ove 550’s 55,3 in, Vhe i B650's loi ks are \et\ similar tv'* the forks found on Ibe new CB750 Beveled stanchion tube edees .¡¡low fork oil to move in between the rubes and sliders, reducing static friction und improving small-bump compliance lie 650 has more front wheel travel as well. 5.6 m compared to the 550's 4 8 in, Vhe usual i VQ (full variable quality) Showa shiK'ks are found on the rear of the 650

Honda tom Star wheels with reversed. high lighted black spokes are mounted front and rear with cither Bridgestone Mag Mopus 3.50H-19 and 4.50H-17 or Dunlop I'll 3,5011-19 and KS7 4.5ÖH-17 tires, for this test, we rode two CB65ÖS, I he first hike, used lor photos and for the dragstrip. was fitted with the Bridgestone tires. The

second bike, used for street and high performance handling evaluation, was fitted with Dun lops. Not surprising, in light of our recent lire tests, we found that the Bridgeslones cornered better but didn't stop or accelerate as well as the Dunlops. Which tire a given bike is fitted with will affect both dra&strip times and high-speed handling.

v

Hie 650's front brake is an ! I-inch hydraulic disc with the caliper mounted behind the fork leg. Brake feel, action and stopping distances were verv good, but the disc discolored quickly and squealed during stops Vhe discoloration and squeal can be traced in part to the high metallic content pads used hv Honda in recent models to. improve wet weather braking Since the rear brake is a conventional mechanical drum, well sealed against water, the t B650 won't leave the rider without adequate brakes in a downpour, W hat's more, the rear drum brake is contmüabie and exhibits no tendency to lock up and skate the rear end under heavy braking, a problem encountered with mam machine , equipped w ith disc brakes front and rear.

As usual, the instruments found on the new Honda are excellent easy to rend day and night, with stable needles and tin proved accuracy It used to be that we'd lind Honda speedometers with errors ofup to 10 pereent. In the case of the 650 the ...speedometer read 60 mph at an actual 57.

which isn't bad And along with the ex peeted. the 650 has several new and interesting touches. 1 he instruments and headlight are shock mounted via supports that fit into rubber donuts in the upper and lower triple clamps, 1 he fuses are located underneath a plastic cover right on top of the upper triple clamp, easy to get at w hen necessary. Because the fuses aren't under

che seat. Honda engineers were able to enlarge the airhtxx. an important factor, we're told, in increasing engine performance while meeting noise and emissions requirements.

Controls are good and easv to find with gloved hands. Sutlers were divided over whether or not they liked the irregularlyshaped turn signal switch, which demands a long throw to turn on the blinker. In actual practice, the switch did its job

The turn signals themselves have plastic, chrome-plated semi-rectangular bodies, are rubber-mounted and secured hv a smgie screw each to tabs welded on the rear frame and bolted to the lower triple clamp

Of course, w hat really counts is how the total package works At the dragstrip, the CB650 turned 13.39 seconds at 98,36 mph 1 hat’s slower than the standard Kawasaki K/650 tested in I ebruary. 1977, which turned 13 19 at 98 46 But the 63’’ce sohe < B65Ö weighs 4/j¡a|Upwtth halt a tank of ' gas. compared to The xtand^^^i3ee dohe Kawasaki K/.oMfs háíf-taof 493 lbs. That l9.pr^^ittU*rct!e!neith To fully appreciate the weight-saving ingenuity Honda’s engineers have shown, consider that a standard Yamaha XS650E Twin weighs 4 lb. more than the CB650. 478 lb. When the CB650. which has a fat rear tire and ComStar wheels, is compared to a similarly-equipped Kawasaki KZ650SR. the weight gap widens and the performance comparison reverses—the KZ650SR has cast wheels, a fat rear tire and a half-tank weight of 501 lb. Tested in August. 1978. the KZ650SR turned the quarter mile in 13.40 seconds at 96.87 mph. Other factors which may have influenced the comparison of times are standard equipment tires (as noted earlier) and the fact that the 1977 KZ650 didn’t have to meet as stringent noise or emissions control laws as did the 1979 CB650.

Where the CB650 shines in a comparison is in top speed, reaching 110 mph as clocked by our calibrated radar gun after a half-mile run. In comparison, the KZ650SR went 105 mph (at the time the standard KZ650 was tested, the half-mile top-speed run wasn't used during testing, so no comparison is possible.)

Few people buy motorcycles for dragstrip use. however. Happily, the Honda CB650 makes a great street bike. The engine makes its best power after a noticeable kick at 7000 rpm and screams to the 9500 rpm redline. But there is adequate power below 4000 rpm and good power from 4000 to 7000. The engine feels perfectly comfortable when shifted at 4000 rpm in city traffic, and leaves lights smoothly and reasonably quickly at 2000 rpm and above. But while the Honda runs contentedly below' 5000 rpm, it doesn't have the kind of punch and acceleration the KZ650 does at those engine speeds. Probably because the Honda has 26mm carburetors and the Kawasaki has 24mm carbs. the KZ650 seems to get serious about accelerating at a lower rpm. and has more apparent torque than the CB650 below 5000 rpm.

On the highway, about 5000 rpm in fifth equals an indicated 65 mph. At that speed the engine sends a slight vibration buzz through the bars and seat and blurs the mirrors. The mirrors, like the ones found on the new CB750K, are unusual, the stems are hollow and the heads precisely weighted to alter their resonant frequency. In theory, the mirrors don't vibrate at the same resonant frequency as the handlebars. and so stay clear in a speed range of 50 to 75 mph. The only time that theory didn’t work on our CB650 was at 5000 rpm. an indicated 65 mph—which happens to be our favorite cruising speed.

The transmission is nearly perfect. It's silent, slick and shifts smoothly, with throws that aren't too long and aren’t too short.

Suspension compliance, as usual with new-model Hondas, is excellent, soaking up large and small surface irregularities as well as the suspension units on any motorcycle now available. With the rear shocks set on the lowest preload, however, a 140lb. staffer riding solo could bottom the shocks at the slightest road dip, even at moderate speeds. Setting the preload at the middle setting worked well around town, with the stiftest setting used for faster riding.

We don't particularly care for stepped seats, but that's what people are buying, and that’s what the CB650 has. It is better than most. The possible seating positions are more limited than on the older type of single-level seat, but at least the Honda’s passenger grab strap is located up on the passenger's section of the seat, so the rider doesn't have to sit on it when traveling solo. Seating comfort is often affected by a rider's size and physical configuration, as well as what's in his hip pockets. In our use, the seat became noticeable after 100 miles in the saddle, but it took three times that before we were uncomfortable. It depends upon the person.

On the open road, the CB650 can travel about 155 miles at an indicated 65 mph with bursts to higher speeds—before demanding reserve, yielding 42.0 mpg. On our usual mileage test loop, a mix of street and highway riding, the CB650 delivered 48.5 mpg at mostly legal speeds.

Like the 550 before it, and in spite of the oversize rear wheel and tire, the CB650 is at home on twisty roads. It wants to turn, so the rider doesn’t have to wrestle the machine down into a curve and then pry it back up after the apex. Steering is neutral and precise. Cornering clearance is good— metal tips on the footpegs touch down and sound a warning first, followed by the stands on the left side. We didn't get anything to grind except the footpeg on the right side in spite of spirited street riding on twisty roads.

continued on page 142

HONDA CB650

$2499

continued from page 60

Because there was a road race handy, the 650 was entered in the Box Stock class, where it did well (winning its class) and revealed an interesting (if terrifying) handling characteristic.

On the warmup lap before the Box Stock race, the CB650 went into a terrible wobble on the long straightaway at about 90 mph. tankslapping—the bars moving back and forth almost to the limits of available steering lock—so badly that the expert rider had no control of the machine momentarily and at one point thought he was going to crash. The bike had exhibited less serious wobbles during practice, but not all the time and not always at the same points on the racetrack. During the race itself the bike was generally stable on the straightaway.

The answer to the riddle came in two simple, yet easy to overlook, parts. Our rider normally sits upright during the first practice session and on pre-race warm-up laps while he checks out the track and bike, but tucks in during races. The wobble occurred only with the rider sitting up.

Yet with the rider sitting up at similar speeds on the street, the bike hadn’t wobbled. The key lies with the mirrors. The CB650 was designed and tested by Honda with two mirrors—one on each side—in place. Mirrors are removed for racing, and unlikely as this sounds, the bike wobbled at speed with the rider sitting up and the mirrors off; didn’t wobble with the rider tucked in and the mirrors off; and didn’t wobble with the rider sitting up and the mirrors on.

Odd. Something about wind pressure, or the damping effect, or a change in ride height fore and aft because of rider profile or the drag coefficient of the mirrors has a marked effect on stability.

We have read about this in the technical literature, and we’ve experienced it with other bikes, although we didn’t know then w hat it was and we don’t know yet w hy it is. We will experiment further.

The stock 650 shocks, though, did disappoint. For high performance use, the first thing a rider should replace is the rear shocks, which heat up quickly and fade during hot laps, especially on a bumpy track. More pre-load on the front fork— which is perfect for a nice, compliant, cushy street ride—would also improve high-speed handling. As is, the bike shook its head in fast, sweeping turns, especially after hitting a bump, even with the rider tucked in. Suspension must take some of the blame for that behavior, while the 17inch Dunlop rear tire’s huge, flexible sidewall must take its share as well. For cornering, we believe that the Bridgestone Mag Mopus tires would work better than the Dunlop Fl 1 and K87 tires. There may be additional choices soon, as several tire manufacturers are building high-performance tires in the 4.50-17 in. size. At least one of those manufacturers—Metzeier— says that its development of an all-new' 17in. rear tire was done on the racetrack with road racers doing the testing. None of the new aftermarket 17-inchers were available for use on the 650. so we’ll just have to waif and see.

For street use, the CB650 handles well as it comes out of the box. If we hadn’t taken the bike to the racetrack, we never would have discovered its flaws—it’s that good on the road. Perhaps more impressive, though, are specific features designed to make the CB650 easier to maintain for the average owner. Removing six bolts releases1 three covers and provides access to the valve tappets. Those three covers are sealed with T-shaped neoprene gaskets that should—barring pinching during installation-last forever. So much for buying a new' cam cover gasket every other adjustment.

Of course, the inductive, electronic ignition has no points and requires no maintenance. In the case of the dohc CB750K. removing the spark plugs is just about impossible without removing the gas tank. But accessibility to the CB650’s plugs is excellent.

Those are small things, perhaps. But it’s refreshing to note that a motorcycle manufacturer has kept in mind such things as initial purchase price, weight and the ability to be serviced by the owner. Honda’s engineers could have made the 650 more complicated and faster and heavier and more expensive. Instead, they built a motorcycle which works overall as well as or better than its competitors, costs less for the features delivered, and is easier to maintain.

The CB650 is a good motorcycle, and anybody in that size market should check it out. IS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontWhy the Future Isn't My Secret

February 1979 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1979 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound-Up

February 1979 -

Short Strokes

February 1979 By Tim Barela -

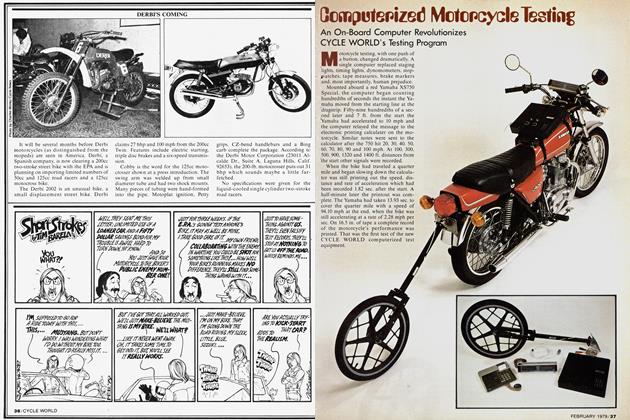

Technical

TechnicalComputerized Motorcycle Testing

February 1979 -

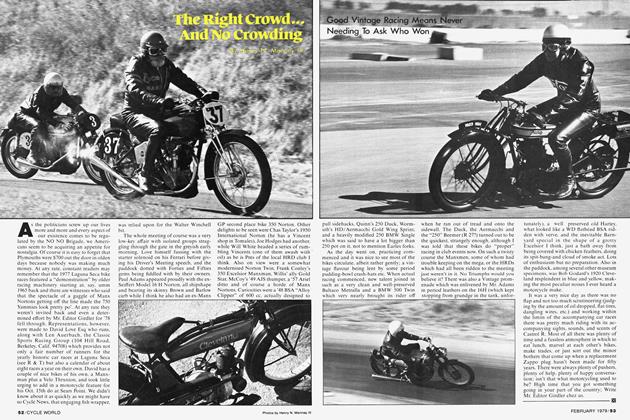

Features

FeaturesThe Right Crowd... And No Crowding

February 1979 By Henry N. Manney III