ADRIFT IN LOTUS LAND

If It's Sushi, This Must be Japan

"How would you like to go to Japan for a week and ride the new Yamahas on their test track?” the Editor asked me.

In the big league of rhetorical questions this one ranked right up there with, “How about a tremendous raise and a free company car?” and, “My parents are in Tahiti; would you like to come in for a drink?” “Why yes,” I said agreeably, “I think I’d like that.”

Japan.

What I knew about Japan you could put in a sake cup, with quite a bit of room left over for sake. My knowledge of Japan and its people consisted mostly of confused images left over from Teahouse of the August Moon, Shögun, Tora! Tora! Tora! and dinner at Benihana’s of Tokyo. Not to mention various Kurasawa movies popu-

lated by quick-tempered Samurai-heroes who go for their swords when agitated by mortal enemies, argumentative wives or excessive bar tabs; the men who first elevated grumbling and muttering to the status of the seething threat.

And then there were the products of Japan. I knew about those. There was a time when objects manufactured on those islands had a reputation for all the enduring, peerless quality of party favors on New Year’s Eve. There were toy cars that said Blatz on the inside when you peeled away the painted tin, cap guns made of those uniquely Japanese materials, chromed plastic and slag by-product, and discount tool tables piled with alien wrenches that twisted like candy canes, hacksaw blades with teeth of butter, and rubber mallets with heads that flew off.

Mattel and Estwing did it better. The words Made In Japan branded on any consumer item suggested a sort of active, spontaneous disintegration going on within the molecular structure; if the product did not actually fail as you were leaving the store, it would almost certainly collapse in service. Japan was the fountainhead of the stripped thread.

Peter Egan

But sometime during the late Fifties or early Sixties that image began to change. Names like Sony and Nikon and Honda began to appear in the stores and showrooms, names that inspired cautious admiration rather than a quick dismissal. Many Japanese products progressed from being cheap copies to good for the money to just plain good. The Japanese became masters of industrial design. The handmade, carefully crafted items from America or Europe might have more romance, prestige or lasting value, but in some cases the Japanese developed mass-produced goods of such quality they set new standards for others to follow. The Made in Japan stamp gradually shed its early, derisive overtones.

This slow blossoming of acceptance, or maybe its full bloom, led to a very strange

moment I had in my own living room a year ago. I was listening to Mississippi John Hurt on my Japanese stereo system, thinking how nice it was to have a new Japanese turntable to replace the more expensive old English one that had never worked right from the moment I lifted its unfortunate hulk out of the styrofoam packing. My attention wandered and I looked around the room. Next to the stereo on a guitar stand was an inexpensive but nicely made Japanese guitar, and on the bookshelf sat a Japanese 35mm camera. Our china cabinet was piled with Noritake cups and dishes, and stored in the basement below were some Japanese skis. Looking out the window I could see our Japanese car in the driveway, and in the garage was a Japanese motorcycle (next to a slightly less reliable one from another country). My wife, Barbara, wandered in from the back porch and said, “Would you light the hibachi?”

“Sure,” I said, glancing at the pulsing LED numbers on my absurdly cheap Japanese watch. “What are we having?”

“Teriyaki beef.”

It was alarming.

Through no conscious pattern of our own design, the house was virtually swamped with Japanese paraphernalia. Our very home was a heavy spot, a lead weight in the wheel balance of world trade, capable of throwing the globe into a crazy tank-slapper.

Who were these Japanese, anyway, and how had they done it? How had a country the size of California, halfway around the world, produced so many things we wanted or needed? (In all fairness to the productivity of California, we also owned a Beach Boys album and a half-empty jug of Gallo Hearty Burgundy). How had these people managed to get a hand in every aspect of our lives?

These questions were obviously too complex for anyone to answer, least of all a motorcycle journalist on a one-week Yamaha junket, so I decided to forget all about them and concentrate on having a good time.

The 747 airline flight was pretty routine, if extra long; 1 1 hours of short naps punctuated by endless bottles of Almadén Pink Chablis, nice little meals in plastic sectioned trays served at odd times and reading the airline magazine from the seatback pouch to learn “How the Dutch Raise Their Tulips” and that “The Spirit of Strauss Lingers on in Old Vienna.” Sanitized headphones were handed out and we watched Breaker Morant, a wonderful and depressing Australian movie, while the airplane whirred and hummed and buffeted. The pilot announced that the Space Shuttle was, at that moment, somewhere off our port wing on its landing approach to Edwards AFB, so we all looked out the window but couldn’t see it.

A Japanese gentlemen across the aisle from me rose to go to the men’s room, but first put a white surgeon’s mask over his nose and mouth. I was told that the Japanese, leary of germs, often wear these masks in public places. He returned to his seat and put on the stethoscope-like headphones to resume watching the movie. He looked like a Japanese Marcus Welby, checking on the health of his own chair. I supressed a temptation to have him look at my tonsils.

There is a lot of Pacific Ocean between the U.S. and Japan. That the Japanese and American fleets ever found each other in WWII is a testament to man’s perseverance in seeking out and attacking his fellow man. The peaks of the Aleutian Islands rose out of the haze here and there, but the rest was hours of empty water. The pilot spoke on the intercom to explain that, while we’d left L.A. at 11:30 Saturday morning, our 11-hour flight would put us in Tokyo late Sunday afternoon. I am sure this is possible, but someday I’m going to get a dark room, a flashlight, a grapefruit and a piece of string, with perhaps eight volunteers to represent the other planets in motion and we’ll all give it the Mr. Wizard treatment to see if it makes sense. Drinks will be served.

We spotted the hazy coast of Japan at sunset. A childhood spent viewing the coast of Japan through periscopes in submarine adventure movies had led me to believe this event would be accompanied by the clanging of a huge gong, followed by the sinister chiming of Oriental stringed instruments. This does not happen. You look at the coast of Japan for the first time and it just sits there. It’s nothing but a big piece of land with people living on it and a lot of buildings and roads. No music.

The plane landed at the New Tokyo International Airport at Narita, a place of great controversy in Japan because of all the farm land it absorbed. Tight security in and around the airport showed they were still worried over threats of violence against the new facilities. The nine of us, five American and two Canadian journalists, plus Ed Burke and Dan Dwyer from Yamaha, got through customs quickly and boarded a special tour bus for Tokyo (Narita is about two hours from the center of the city). A Japanese woman guide described the points of interest en route, though we couldn’t see them because it was dark outside and the bus had bright neon lights inside. We could see our own*reflections in the bus windows, however, and some of us looked quite good. The guide explained we needn’t be afraid of drinking the water anywhere in Japan because it was all clean and safe.

We were delivered to the imposing Hotel Pacific in downtown Tokyo and* given time to find our rooms, change, shower, gather our wits, etc. before dinner. The room was nice, sort of American style but simpler, with less gilding and Spanish woodwork. It had a color TV, a big modern bathroom complete with disposable razor, toothbrush and toothpaste, and a handy wall telephone next to the toilet. This despite the good quality of the water. Every room was supplied with a robe-like kimono for each guest (or at least my room was; I was too tired to check the other 300 rooms to see if this was true). A card on my desk said “Massage in room: 3300 Yen for 50 minutes.” That was about $14. I could have used a massage, but had heard that another member of the motorcycle press had taken advantage of this service the previous year and they’d sent him home laid across two airline seats. He was only now accepting visitors.

I turned on the TV and there was Lee Marvin, dressed as a small town cop, arguing in Japanese With a torch-bearing mob of American rednecks. I switched around and discovered that nearly all Japanese television ads contained some English, usually in their slogans. A Japanese housewife serves instant soup to her family, then holds the package up to the camera and says “It’s nice!” An ad for blue jeans announces, “They are cool!” The neon signs on Tokyo streets were also loaded with American phrases. I switched over to the news and managed to decipher an announcement that William Holden had just died. They showed lengthy clips of his films.

The porter brought my bags, bowed politely and left without the normal throatclearing hesitation and tip ritual. I learned that tipping is seldom practiced in Japan, and restaurants add a 10 to 20 per cent service charge to the bill automatically. This certainly simplifies travel and mental calculation, and the service is generally so gracious everywhere the American tradition of witholding a tip in revenge for rude treatment doesn’t apply.

We had dinner that evening in the hotel’s traditional dining area, traditional meaning private rooms with sliding rice paper walls, no shoes, waitresses in Madame Butterfly garb, and low tables (some with cheater footwells for Americans who can’t kneel through a three-hour meal—or for those who can kneel through a three hour meal but are never able to walk again if they do). We had sushi first, raw fish and vegetables cooked in a soy-flavored sauce at the table. The beef was excellent and we were told it came from Kobe, where the cattle are fattened on a beer diet and massaged by hand to help marble the meat. This is different from the American agricultural system where the farmers drink all the beer, the cattle go thirsty and the average Hereford or Angus finds a good massage hard to come by. But then beef in the U.S. is cheaper, too. Kobe beef costs between $40 and $80 per pound, depending on whose exaggeration you believe.

Kirin, a good Japanese beer, was served from huge bottles, along with plenty of sake, hot rice wine poured from steaming stone vessels into tiny cups. Sake was served every night on this trip, and on cool autumn nights it quickly promotes a spreading warmth and a sense of wellbeing not found in Diet Sprite, for instance. I began to like sake, then look forward to it, and by Friday I’d developed regular craving for the stuff. If seven o’clock rolled around and I hadn’t had any sake I began to suffer a nervous tic in my left eye. The use of sake should be outlawed in the U.S., just to make sure everyone gets a chance to experience this enjoyable habit.

The traditional Japanese meal takes long time to eat and drink; hours spent stirring things, dipping in sauces, sipping from cups, all the while carrying on lively conversation. I looked at our friendly Japanese hosts, laughing and talking and eating, and wondered if they realized they were missing Dallas.

After dinner we retired early, as it was now mid-morning back in L.A. and we were all clobbered by jet lag. I went up to my room and turned on the T.V. Dallas was on. An overdubbed J.R. was busy losing the Ewing family fortune over the phone and everyone else was off cheating and sleeping around in Japanese. switched channels and found sumo wrestling.

Sumo is an ancient sport where two very hefty men in loincloths try to shove each other out of a small circle, after a lot of pre-fight posturing and ritual. Our guide told me these men live a very rigid lifestyle and are trained (overfed) from youth. They do their workouts in the morning and in the afternoon drink beer and receive massages. I began to wonder if there was any living thing in Japan that didn’t drink beer and get its back rubbed. I also wondered what a 350 lb. sumo wrestler does for a living when his ring career is over and he has to hang up the loincloth. I asked one of our Yamaha friends.

“Anything he wants,” was the reply.

I’d just finished dressing in the morning when there was a knock at the door. I peered out and a wizened little woman in a chambermaid’s outfit waved a vacuum cleaner nozzle at me.

“Hoover?” she inquired.

“No thanks,” I joked, “we’re Democrats.” >

This cut no ice with the little lady, so 1 let her in and she Hoovered my room while I went downstairs to Hoover up a little breakfast.

We boarded an elevated train near the hotel and rode down to the Ginza district, an area of huge, classy department stores, theaters, camera shops, etc., Tokyo’s own Fifth Avenue. The best entertainment of the morning was watching the renowned motojournalist, Dale Boiler, blow thousands of dollars on oddball camera attachments, pearls and multi-purpose wristwatches. Dale can now take underwater flash photos of marine life at depths that would crush a submarine and play ping pong on his wrist.

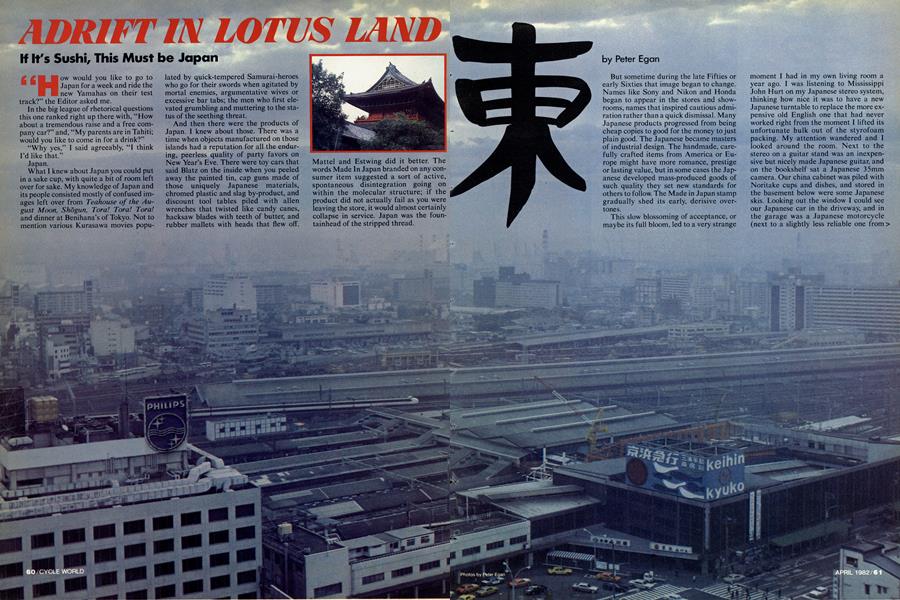

Tokyo is a huge, clean, mostly modern city, a hodgepodge of new skyscrapers, small parks, ancient temples, modern apartment buildings, traditional old residential neighborhoods full of artfully curved red tile roofs, colorful sidestreets of tiny shops, manufacturing plants, railroad yards and busy streets. The city is notably devoid of garbage, graffiti, litter and unkempt buildings. Our guide Mr. Ikeuchi, told us we could go anywhere at any time of the day or night in Tokyo, as street crime and violence are extremely

rare. Walking around the city we all noticed that no matter how plain or humble a shop, restaurant, house or courtyard might appear from the outside, it was always much nicer inside. Japanese interiors have a simple serenity about them that is very restful.

Viewed from the elevated train or the freeways, Tokyo is unimaginably large. Its flat expanse stretches off to the horizon in all directions, a vast landscape of factories, towers and houses. L.A. is a big city too, but it has a downtown of skyscrapers clustered together, surrounded by miles of one and two story structures. In Tokyo the tall buildings go on forever. The city is terribly crowded, but the people seem to handle it better than citizens elsewhere in the world. Politeness is rampant.

We caught a taxi back to the hotel. Tokyo’s streets are full of new-looking Japanese cars, many of them large luxury

models only now beginning to appear in the U.S.You see hardly any rusty,dented or half-primered old cars for some reason. The beater, the Japanese counterpart of every car I’ve ever owned, is absent from the streets. There are a lot of motorcycles, but not as many as you might expect in this bike-producing country. You have one big group of 50 to 250cc commuter and delivery bikes, ridden mostly by students, or construction workers who wear tall rubber boots, helmets that look like hardhats with liners, and big gloves, many smoking cigarettes as they ride. There is another class of sporty Twins and Fours in the 400cc range, owned largely by welldressed young men in full-face helmets and nice leather jackets. Above that you have the truly committed crowd, men 30 and over who have spent the money and taken the trouble to buy big foreign iron; Harleys, BMWs and Ducatis. Or they have re-imported big Japanese bikes, brought back from abroad to get around the 750cc maximum rule for domestic motorcycles. A couple of the Harley riders we saw were older men dressed in state trooper look-alike regalia. A lot of the smaller bikes do delivery duty, piled high with crates and boxes on pallet-sized luggage racks. Few women are seen riding motorcycles larger than those in the moped class.

In the afternoon we boarded the Superexpress, the famous “Bullet Train“ and headed south to Iwata at what was supposed to be 135 mph, but the luxurious train was so smooth and quiet it was hard to gauge the speed. The tracks use concrete ties and the rails are seamless. How they do this, I don’t know. There are no visible welds. Journalist Ken Vreeke fantasized a sort of rolling steel mill, extruding track as it went along. Then he opened another bottle of Kirin.

South of Tokyo fields and farms opened up, dotted with small villages stuck in the valleys and hills. Rounded hedges of tea plants were everywhere, in back yards and along the roadsides. You have only to look at the Japanese countryside to see where their landscape art comes from. The hills have a rugged, hazy look, dotted with rock outcroppings and small growths of trees above the tea and rice fields, all with a slightly mystical look.

Even in rural areas, the country is well populated. Villages are close together, farms are small. There seem to be few open roads where you could ever get a CBX or an XS11 much past third gear without running into another pocket of civilization.

Traveling cross country in Japan you begin to understand the volume of competitively-priced Japanese goods in American stores and homes. As England realized, at one time, a small, crowded island country with few natural resources has to survive on its wits and innovative energy. Trade is essential. They have to figure out what the rest of the world will buy and then make it. That produce-or-perish mentality may not be as strong in other parts of the world because the lesson is harder to teach. The Japanese need only look out their windows to understand. It’s crowded out there.

Cabs took us from the train station to our hotel in Iwata, the home of the Yamaha motorcycle plant. Riding in a Japanese taxi is one of the few things that will make a grown motorcycle road racer cry. On the way to the hotel our cab driver careened through the narrow streets of Hammamatsu honking at blind intersections, swerving around pedestrians and bicyclists and scraping between delivery vans and the walls of buildings like a runaway fire truck in a silent movie. You have to ride in Japanese cabs with a relaxed fatalism or you’d go mad with fear. At one point our guide said, “We are almost there,” and a voice in the back seat muttered, “Don’t count your chickens.”

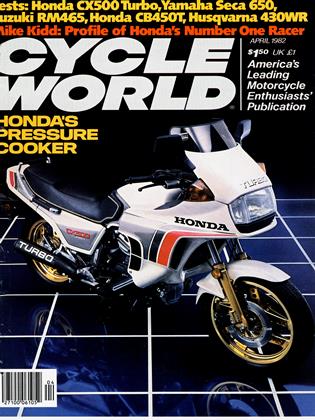

We were asked to suit up in our leathers right away and a bus took us just out of town to the Yamaha test track. The track is a beautiful, smooth road circuit that winds around a wooded hilltop in a setting similar to Watkins Glen. We were given a briefing on track safety and layout and then turned loose on the track with five of Yamaha’s new U.S. road models: the 650 Seca, XJ650 Turbo, 550 Vision, 920 Virago and the 750 Maxim. We took the bikes out for 15 or 20 min. sessions, then came in, talked to the engineers for first riding impressions, traded bikes and headed back out. The following day we were given a number of tech sessions and six or seven hours of track time. Long enough to find out Yamaha has produced some impressive street bikes this year, much to the satisfaction of the journalists on the tour. A day with the engineers is always much more pleasant when you genuinely like what they’ve done.

Before Bullet Training back to Tokyo we were given tours of the Iwata motorcycle factory and the Nippon Gakki plant where Yamaha pianos are made.

At the bike factory the stamping and machining of gears, shafts, etc. is mostly automated, but the final assembly line is handwork and the most interesting to see. There’s something strange about watching bare frames come down from the ceiling on hooks at one end of the assembly line while at the other end, just a few hundred feet away, completed machines are started up and ridden away. Last time I restored a bike and assembled it from parts it took me about six months, and starting the rebuilt engine for the first time was a dramatic event to rival the first manned flight. Yamaha was turning out a new living, breathing 550 Vision about every 30 sec., fully expecting each one to start and work just fine.

Not all of them did, of course. While we were there one bike came off the line with a loud exhaust leak and another one developed a steamy coolant leak while it was being run up on the dyno. Several others were sidelined for coolant leaks. “Bad> batch of hose clamps,” the guide explained. “We’re replacing them all.” The combined Yamaha assembly lines turned out 8000 bikes a day, or one every 3.4 sec.

The green-clad employees in the assembly line were models of careful work and concentration. No one gave the tour group and its flashing cameras more than a passing glance. The women in the line all wore multi-colored aprons with cartoon characters on them. In English lettering the aprons were emblazoned with such titles as, “Tweety Pie,” “Tom & Jerry Tennis”(?), and “Happy Cats.” Happy Cats was a big favorite.

The most exciting bit of assembly line technology for the visiting journalists, because so many of us have spent time chasing ball bearings under workbenches, was the installation of steering head bearings. The workman was dipping a ring-shaped vacuum attachment into a huge keg of ball bearings, shoving them into the grease of the steering head cups and then releasing the vacuum. We watched in amazement. “So that’s how they do it,” said Editor Larry Works, “they have a bearing Hoover.”

We visited a soundproof room for sound testing, a frosty refrigerated room for temperature testing and walked past a 250 Exciter being torture tested by a mechanical rider whose electronic brain was strapped to the back seat. We watched a technician throw a frame design up on a green computer screen and then feed cornering stresses into it, causing the frame to flex and twist with mathematically exaggerated severity. In each department people appeared to be absorbed in their work, moving steadily and efficiently but never rushing. “We make our assembly line so workers don’t have to hurry too much,” our guide said. “Not good for quality to hurry. Also we have 10 model changes a day on different assembly lines. That way workers don’t always do the same thing.”

After the tour we were bussed to Lake Hamana, where Yamaha Corp. owns a resort called Marina Hamanako, a vacation spot for company employees who join a recreation club. A cocktail party was thrown so we could meet all the Yamaha executives. If this has all the makings of a stuffy affair, it wasn’t. The Japanese take their work seriously during the day, but at night they relax and become good-humored, affable company. Throughout the trip I can’t recall meeting a single sour or ill-tempered personality. Such people are either rare in Japanese society, or they were being hidden for our visit. Even Yamaha’s upper level executives, no doubt burdened with considerable responsibility, were largely an easy-going, likable group whose good nature and wry humor made it through the language barrier with no problem. Meeting these gentlemen it is easier to understand why Japan has fewer conflicts between labor and management than many other countries. As executives, they seemed remarkably free from pretensions of authority, bluster and other overbearing behavior, acting instead with a sort of alert humility that suggests they got to the top on merit and hard work; that they live in a society where actions speak louder than loud words.

I may be wrong about all this, of course. But after a few drinks they all seemed like a splendid bunch of fellows.

We took the Bullet Train back to Tokyo, eating salty dried squid (Japanese counterpart to pretzels) and drinking Sapporo beer from a vending cart that rolled through the train. The Tokyo skyline loomed into sight, a grim and sobering reminder of how many Japanese monsters, from Godzilla to Rodan, have devastated that landscape in their clumsy battles; squashing cars, running afoul of high tension lines, swatting down jet aircraft, shrugging off white phosphorus rockets and shaking the terrified passengers out of elevated railway cars after first peering into the windows. Sure, the crime rate was low in Tokyo, but those monsters! Talk about vandalism.

On our final evening in the country our hosts took us out to a little sidewalk cafe on a sidestreet in Tokyo, practically under the girders of the elevated railway. We drank beer and sake and had dozens of courses of skewered meat and vegetables cooked over an outdoor charcoal brazier. And of course plenty of raw fish, which, like the evening sake, had grown on most of us during the tour. Mr. Ikeuchi suggested we sing some songs, and it turned out that he and another Japanese gentlemen who was with us not only had excellent voices but knew dozens of American folk songs by heart. We sang Swanee River, She’ll be Cornin’ Around the Mountain, Davy Crockett and other standards. They knew most of the words better than we did. A group of college students at the cafe moved their table next to ours so they could join in the singing. One of them said in halting English that his sister was going to college in Santa Barbara, California, then stood up and did a perfect imitation of Frank Sinatra singing Strangers in the Night. Then we all toasted him and his sister and Frank Sinatra and Santa Barbara. People passing by on the sidewalk stopped and joined us in some of our songs.

They knew the words too. Other people stopped and bought us rounds of drinks.

This sort of thing doesn’t happen to Americans in Europe, or anywhere else I know of, including America. The Japanese may not always understand the crazy Americans, but they know a lot of our culture and freely adopt many of its better aspects. There is a friendly, open curiosity at work here, and that may be the great strength of the Japanese. They would rather learn about something new than complain about it. (I personally prefer to learn just one or two simple things and then leave well enough alone.)

At Narita airport we sat in the restaurant and waited for our flight home. A tour group of middle-aged American women sat down at the next table and it took them about five minutes to reduce our young waitress to tears because (a) she didn’t speak English clearly and this was, after all, an International Airport and (b) because she brought the wrong order to a 300 lb. matron who had a fox fur around her neck and didn’t have to put up with this kind of treatment. I wondered if they thought the American waitresses at the airport coffee shop in L.A. all spoke fluent Japanese. Or any Japanese. Or even good English.

We couldn’t watch any more so we got up and left. After we’d been around the graciously polite Japanese for a week, these women seemed about as civilized as a gang of buffalo hunters. How, with all the wonderful Americans we had back home, did we always manage to produce such a dismal brand of tourist?

These women aside, we were all anxious to get home after a week in Japan, for various reasons involving families, clean socks and chocolate milkshakes. One of my own reasons was the old elbow-room problem. In the U.S. many of us might be crowded into cities, but in the back of our national mind we knew the open spaces were out there, just over the next hill; mountain ranges, prairies and half-empty states with wide-open roads. Our sense of geographical scale was all different. The parts of Japan we toured, beautiful though they might be, were like one continuous neighborhood, broken here and there by hills and fields. Such places give me a sort of geographical claustrophobia. I could enjoy living there for a time, but not forever. No one has to be knocking around in the wilderness or riding down lonely roads all the time, but it’s nice to know such places exist when you get in the mood.

Clicking a fast machine—say a Turbo 650—into fifth gear on an unpopulated, unpatrolled country road is important to some of us; a state of mind and a kind of evening sake to the human spirit. Not a strictly legal thing to do, but then as Americans we have a tradition to uphold. Leaving any foreign country, I’ve always come away with the conviction that irreverence is still our finest export. BS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue