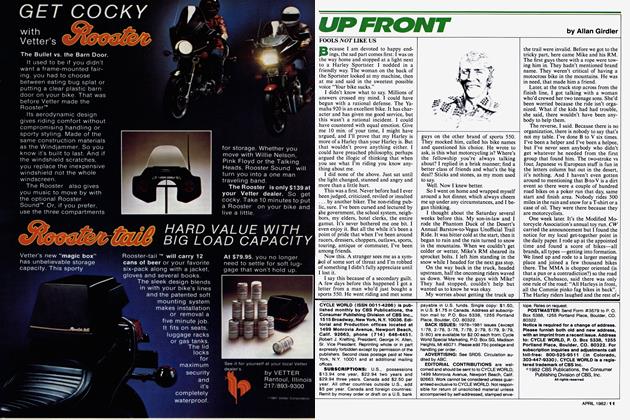

1915 EMBLEM MODEL 110

Big, Blue and Fast, the Emblem Raced to Fame and Faded to Obscurity

John Ethridge

Scattered among the Harley-Davidsons and Indians and more recent British bikes that form most of any antique motorcycle meet are the less common names. Pope and Cleveland and Pierce and Excelsior and dozens of others didn't last long enough to retain their

fame. And on the fringe of fame even 70 years ago were even more obscure names.

Emblem was one of those.

Many a hard-fought race and 70 years of arguments have failed to resolve what was the best motorcycle of the period, but the handful of old-timers still with us who were familiar with them, as well as leading collectors and restorers, agree that the Emblem was certainly one of the better ones. Emblem Manufacturing Co., Angola, New York (a country town southwest of Buffalo) was originally a successful bicycle manufacturer. In 1908 its proprietor and chief designer, William G. Schack, having been bitten by the motorcycle bug, brought out one of his own. His first effort was a single-cylinder, single-speed with a slippage-prone flat-belt drive, but it was successful enough to launch the company into the motorcycle business. Two-cylinder engines, some with vee-belt drives, soon followed.

Competition success, which had a direct and measurable effect on sales in those days, came early too. In August 1910 an Emblem set a New York-to-Chicago record of 35 hours over some 800 miles of bad to atrocious roads. And what was to be the most glorious single day in Emblem’s history came in 1912 when it swept the Labor Day races at Springfield, Ohio, taking the 3-, 5-, 6-, 8-, and 15-mi. events and gaining fame that extended beyond the shores of its native land. The field it humbled on that day contained many brands, including all of the big ones. Initially, the Emblem badge was a low-key affair, modestly showing only the brand name and the name and address of the manufacturer. But the one finally used on the larger Emblems was a real totem, depicting a greyhound at full stride and a spread eagle perched on top to reflect the maker’s pride in its achievements.

In 1913 Emblem announced a new Twin to head its lineup which, with a bore and stroke of 3.5 X 4.0 in. for 76.6 cubic inches displacement, was the largest of its day, and it remains one of the largest production motorcycles ever made. Magneto ignition and chain drive, either optional or unavailable on the other models, were standard on the Big E. Here, for 300 1913 dollars, was the ultimate combination of reliability, performance, prestige, conspicuous consumption, overkill, macho—you name it—that could be found on two wheels.

This series, which the factory designated the Model 110, was produced through the 1916 model year. The example featured is a 1915 model, meticulously restored by Steve Wright of Huntington Beach, California, one of the few known to still exist. Thanks to Steve, who took the bike completely apart, its technical details, many of which are unique or unusual, can be brought to light.

The engine is a 45° V-Twin, a classic arrangement used by many bikes because of its many advantages, not the least of which being its lean, good looks. The crankshaft runs on a pair of double-row ball bearings, and the blade-and-fork connecting rods operate on a three-row roller bearing at the crank throw. This robust lower end design was exclusive to Emblem, Steve believes, because all of its many contemporaries that he has worked on used plain bearings. Following general practice of the time, there were no smallend rod bushings or bearings, and the wrist pins floated in rods and cast-iron pistons. Two very wide (approx. 3/16inch) piston rings are used, the lower of which crossing the wrist pin hole and acting as a retainer—another Emblem exclusive.

The valves are arranged in an F-head layout, with the intakes overhead and the exhausts on the side. Few bikes of this era used F-heads, but at an earlier time those with atmospheric intakes (no mechanical assistance) did. The camshaft has four separate lobes—one for each valve—and operates roller followers. As was common at the time, the overhead valve gear was exposed and required regular lubrication with a squirt can.

The magneto timing gears are arranged on a plate that slides into a slot in the aluminum crankcase like a desk drawer, an Emblem twist that speeded up maintenance and service. The circular timing cover is threaded into the crankcase so that it can be quickly removed and installed with a wrench. And what must have really endeared the Emblem to mechanics was the fact that the engine, being mounted on a platform, could easily be slid in and out of the frame and attached with few bolts.

The engine lubrication system, primitive by today’s standards but par for its time, uses the drip-fed, total loss principle. The rate of feed, observed through a glass window and set with a needle valve, remains constant at all engine speeds. The rider has to make up for this deficiency with a hand pump mounted on the side of the oil tank by giving the engine periodic shots of oil through a feeder line at his discretion. All oil is either burned or blown out, since there is no engine pump to return any to the tank. Hence the term total loss. The 1916 model was fitted with a mechanical oiler that fed proportional to engine speed, but the total loss system was retained.

The factory rated this engine at 10 horsepower, but this is obviously taxable—not real—horsepower. It is doubtful whether one of these engines has ever seen a dynamometer, but 25 to 30 horsepower at around 3000 rpm would be a good estimate of its true capability. We couldn’t find anyone who has actually uncorked a big Emblem, but Bud Ekins, who has probably ridden more antique bikes than anybody else, thinks 70-75 mph might be possible under ideal conditions.

Getting the engine fired up is something of a chore and requires the following ritual: Open the valves on the priming cups atop the cylinders and, using the syringe built into the gas cap, withdraw some fuel and squirt it into the priming cups. Close the priming cup valves and set the choke on the carburetor. Then begin pedaling, moped style, while actuating the compression release. (This wedges the exhaust valves open so you don’t have to work against compression.) After gaining some momentum, dump the valves and crack the throttle, and the engine thumps to life. On a warm day or when the engine is hot, the priming step can usually be eliminated. Stopping the engine requires closing the throttle and releasing the compression, since no kill-button or ignition switch is provided.

Although a separate brake pedal is provided, the brakes can also be applied by back-pedaling on the starter pedals. This

coaster-brake feature reveals the Corbin contracting-band brake’s bicycle ancestry.

The parallelogram front suspension with cartridge-enclosed coil spring was considered very good in its day, and the design was used for many model years with only detail changes. As was universal on motorcycles then, the rear suspension is rigid, and sprung seats, or saddles as they were called, protected the rider’s spine from jolts. The featured Emblem has a Mesinger saddle, which uses a combination of coils and leaves. Emblem offered a choice between this and Troxel or Persons saddles.

Sharp-eyed antique motorcycle enthusiasts will note that the clutch is missing from this Emblem. The Eclipse clutch had been pirated from the bike, and restorer Wright hadn’t located one when the pictures were taken. The Eclipse is a multi-disc, steel-on-steel design, and crude though this may seem, it worked extremely well and was popular throughout the industry.

The big Emblem has another asset that is undiminished by decades of time and technological progress: a beauty of form and line that is close to what a lot of people, old and young, think a motorcycle ought to look like. Many of Emblem’s contemporaries, worthy as they were, had all the ambience of farming implements. Take an Emblem, remove the patina of age and neglect with some paint and spit > and polish, and the uninitiated will have difficulty believing the design is pushing 70 years of age.

The closing chapters of Emblem’s history pretty much parallel what happened to most of the motorcycles of its time. Competition within the industry itself was such that all of them couldn’t have survived no matter what. But what accelerated the decline of the American motorcycle industry was Henry Ford and his Model T automobile. This upstart of a Michigan farm boy had, through the miracle of mass production, brought the price of his car down to within a couple of hundred dollars of that of the nicer, more desirable motorcycles. During 1916 eight prominent brands of motorcycles disappeared, and for 1917 William Schack announced that he would offer only one model, the single-cylinder Emblem Lightweight.

The Emblem name was well respected abroad and enjoyed some sales success in places like Holland, England, Australia and New Zealand. But this was not enough for a profitable operation, and Emblem Manufacturing Co. closed its doors in 1925.

The years 1912 through 1917 were by all accounts the heyday of the American motorcycle manufacturing industry, both in terms of international esteem and sheer proliferation of makes and models. The larger motorcycle shows of the day typically featured 30 or so brands and maybe twice that many models vying for commercial success. The Motorcycle Belt pretty much corresponded to the geographical location of this country’s machinery and metal-working industries of the time, which was from New England through the Great Lakes and Mid-western states. Any hamlet with an ironmongery and a bicycle shop was a potential site for a motorcycle factory, and many of them became so. No one knows for sure, but it has been estimated that as many as 100odd different brands of motorcycles and motorized bicycles, counting the one-offs and few-offs, were introduced during the first quarter of this century.

They are gone now, all those brands, except for one survivor. And the thousands of early motorcycles that established America as the world’s leading motorcycle manufacturing company are mostly gone, too, except for rare restorations like this.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue