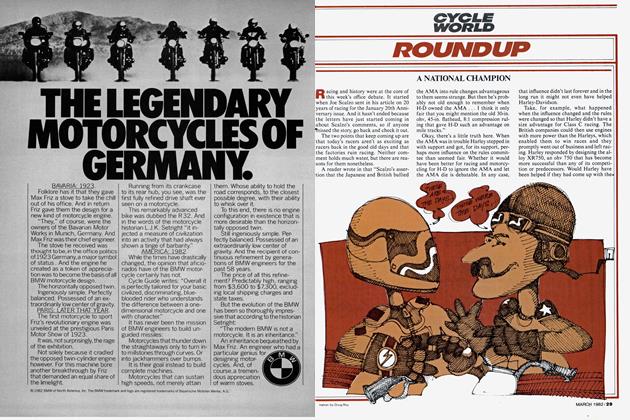

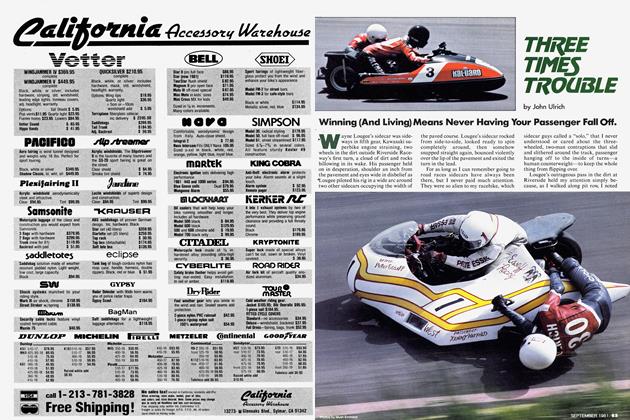

COACHWORK KAWASAKI

Bring Harry Maillet Your Bike and Your Wallet, and Take Home a Superbike for the Street.

John Ulrich

Horsepower isn't as simple as it sounds, and there are motorcycles that give horsepower a bad name. Building a bike with an incredible amount of top speed or acceleration isn’t the same thing as a building a motorcycle that’s fun to ride on the street. Good E.T. aside, a motorcycle that won’t idle or pull well off a corner isn’t much good for street use.

So it’s unusual to find a motorcycle that turns 10.70 sec. and 125 mph at the drags, idles, pulls from 1500 rpm, doesn’t overheat in traffic and runs happily on pump gas.

“The whole key is making it streetable and reliable,” says Harry Maillet, who builds high performance street bikes at his Performance Works shop in Canoga Park, Calif. Maillet is no stranger to racing, having built and maintained Superbikes for Steve McLaughlin a couple of seasons ago. But he’s also a street rider, and he knows the difference between straight-line performance and tractability.

Maillet charges riders $15,000 to turn their stockers into street bikes like the one shown here, stripping the bike down to the bare frame and rebuilding it to suit a customer’s planned use.

Engine modifications start with the crankshaft, which is pressed apart. The center journal is polished and stress relieved, and each connecting rod small end is fitted with a bronze bushing to eliminate wrist pin gauling. As the crankshaft is reassembled, each pin is welded to prevent slipping.

Pistons are 73mm, 10:1 c.r. Moriwaki two-ring pressure-cast, bringing displacement up to 1105cc. Each set of pistons is matched on a scale, and Maillet bead blasts the piston skirts (at low psi) before having Kal-Gard moly Piston Kote applied. The piston dome is not coated, and sharp edges on the piston valve cutouts are rounded off to avoid heat concentration.

The cylinder head is milled to ensure a flat gasket surface, and is ported. Maillet installs stainless steel valves, oversize intakes (37.5mm vs. the stock 36mm) and standard size (30mm) exhausts. Racing valve springs with titanium retainers and shim-underneath buckets are operated by racing camshafts. Intake lift is 10.5mm, exhaust lift 10mm. Duration for intake and exhaust is 265 ° with lobe centers located at 105°.

Threaded steel inserts are fitted into the crankcase stud holes, and a plate is installed beneath the crankshaft to direct extra oil up into the hot-running middle two cylinders. The cam chain is heavy duty, and the cam chain tensioner is modified from automatic to manual. A baffle system in the oil pan holds oil near the oil pump pickup during hard acceleration, and a Lockhart oil cooler with braided stainless steel lines is fitted.

The clutch uses standard Kawasaki fiber plates and Barnett copper-coated steel plates, with slighty-heavier-thanstock P&M springs. The transmission is a Kawasaki close ratio, which is taken apart and X-rayed, then sprayed with Kal-Gard moly Gear Kote before installation.

The ignition is a standard Kawasaki Mk. II system with 38° of advance. Maillet uses 29mm Mikuni smoothbore carburetors and a built-on-the-bike Kerker racing exhaust system. The custom-built Kerker systems are not available to retail customers, and Maillet has his systems built to match state of engine tune. For this bike, the system has 1.625-in. i.d. head pipes leading into a 2.5-in. collector as compared to the over-the-counter racing Kerker dimensions of 1.5-in. head pipes and a 3-in. collector.

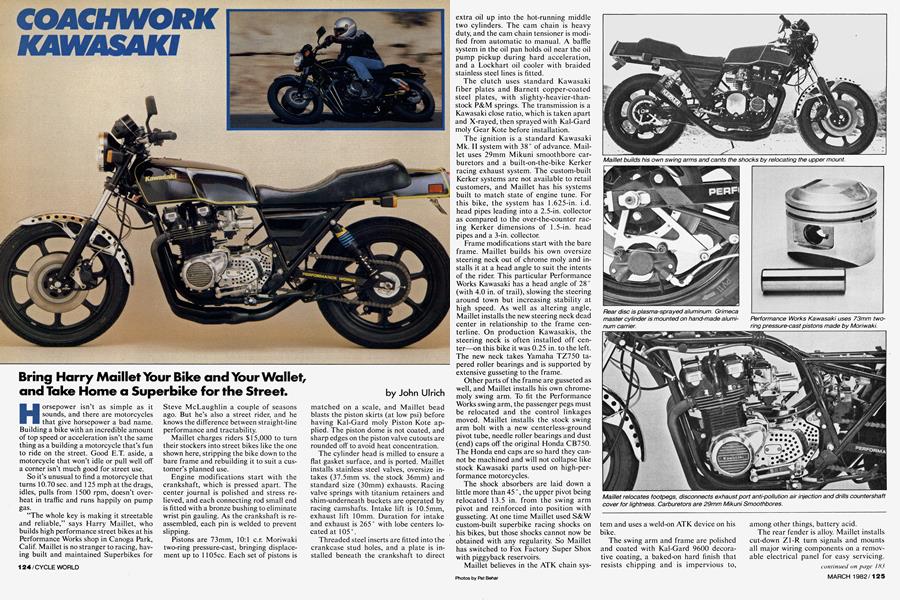

Frame modifications start with the bare frame. Maillet builds his own oversize steering neck out of chrome moly and installs it at a head angle to suit the intents of the rider. This particular Performance Works Kawasaki has a head angle of 28 ° (with 4.0 in. of trail), slowing the steering around town but increasing stability at high speed. As well as altering angle, Maillet installs the new steering neck dead center in relationship to the frame centerline. On production Kawasakis, the steering neck is often installed off center—on this bike it was 0.25 in. to the left. The new neck takes Yamaha TZ750 tapered roller bearings and is supported by extensive gusseting to the frame.

Other parts of the frame are gusseted as well, and Maillet installs his own chromemoly swing arm. To fit the Performance Works swing arm, the passenger pegs must be relocated and the control linkages moved. Maillet installs the stock swing arm bolt with a new centerless-ground pivot tube, needle roller bearings and dust (end) caps off the original Honda CB750. The Honda end caps are so hard they cannot be machined and will not collapse like stock Kawasaki parts used on high-performance motorcycles.

The shock absorbers are laid down a little more than 45 °, the upper pivot being relocated 13.5 in. from the swing arm pivot and reinforced into position with gusseting. At one time Maillet used S&W custom-built superbike racing shocks on his bikes, but those shocks cannot now be obtained with any regularity. So Maillet has switched to Fox Factory Super Shox with piggyback reservoirs.

Maillet believes in the ATK chain systern and uses a weld-on ATK device on his bike.

The swing arm and frame are polished and coated with Kal-Gard 9600 decorative coating, a baked-on hard finish that resists chipping and is impervious to, among other things, battery acid.

The rear fender is alloy. Maillet installs cut-down Zl-R turn signals and mounts all major wiring components on a removable electrical panel for easy servicing. The motor mounts are cast aluminum with grade 12 bolts which fit the mount holes so tightly that they must be driven in and out. According to Maillet, standard engine mounts and engine mount bolts are such a sloppy fit that the engine can rock on the mounts. With rigid mounting, the engine becomes a bracing member and helps hold the frame in place. (The motor mounts, swing arm and a Kawasaki steer ing damper consitute a Performance Works chassis kit which Maillet sells separately.)

continued on page 183

continued from page 125

Maillet modifies and installs a latemodel Kawasaki Mk. II front end on each bike he builds. Depending upon the rider and his projected riding, Maillet may leave the damper rod holes stock or mod ify them. Smaller holes (as used in KYB racing forks) result in stiffer damping and are better for racetrack use. Larger holes reduce damping and deliver a plusher street ride. Maillet also changes spring rates and preloads to suit the intended use of the machine.

Wheels are Morris magnesium (a WM4-19 front and WM6-18 rear) with Hunt plasma-sprayed aluminum discs on cast magnesium carriers and Grimeca doubling-action calipers. Braided stain less-steel-covered dash-3 brake lines are used. The front master cylinder is a 5/8-in. Grimeca. Tires are Michelins front and rear.

"There are places that build engines and places that build chassis," says Maillet when talking about his work, "but very few that offer a turn-key motorcycle. It isn't just product. I spend a lot of time with a customer to find out exactly what he wants to do with his motorcycle, and then I give him what he wants. If he wants a racebike, I build a racebike. But if he wants a street bike to run on pump gas, I give him a street bike. What I strive for is not to have all the trickiest stuff, but to have stuff that really works."

After riding Maillet's Kawasaki at tl~e drags, on the street, and along twisty can yon roads, it appears that he has suc ceeded. This motorcycle feels like a racebike, from very strong acceleration to hard, hard braking to that warble in the exhaust under power that accompanies a high-horsepower engine and a very sticky tire fighting the stick-or-spin battle corn ing off a turn.

But in spite of road-racer performance, handling, stability and braking power, the Performance Works street bike doesn't smoke, idles smoothly and never pings, spits back or acts in any way cantanker ous.

It surprised us, with its civility and good manners, and is the first performance street bike we've seen in a long time that didn't give away street suitability.