THREE TIMES TROUBLE

John Ulrich

Winning (And Living) Means Never Having Your Passenger Fall Off.

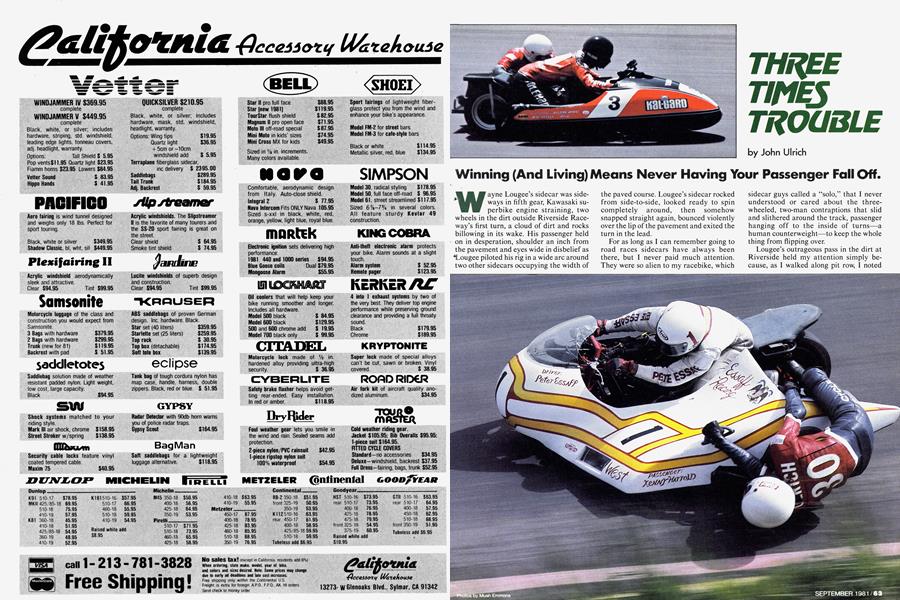

Wayne Lougee’s sidecar was sideways in fifth gear, Kawasaki superbike engine straining, two wheels in the dirt outside Riverside Raceway’s first turn, a cloud of dirt and rocks billowing in its wake. His passenger held on in desperation, shoulder an inch from the pavement and eyes wide in disbelief as Lougee piloted his rig in a wide arc around two other sidecars occupying the width of the paved course. Lougee’s sidecar rocked from side-to-side, looked ready to spin completely around, then somehow snapped straight again, bounced violently over the lip of the pavement and exited the turn in the lead.

For as long as I can remember going to road races sidecars have always been there, but I never paid much attention. They were so alien to my racebike, which sidecar guys called a “solo,” that I never understood or cared about the threewheeled, two-man contraptions that slid and slithered around the track, passenger hanging off to the inside of turns—a human counterweight—to keep the whole thing from flipping over.

Lougee’s outrageous pass in the dirt at Riverside held my attention simply because, as I walked along pit row, I noted three sidecars running abreast down the front straightaway. I wanted to see which one of the three would back off to fit through the two-sidecar-wide first turn. That nobody backed off, and that Lougee was successful in his wild stab for first place, was simply incredible.

Incredible, too, that three years later, in the summertime of 1981 I stand in the pits at Sears Point Raceway, leathers zipped and helmet in hand, waiting to ride on a racing sidecar.

It isn’t Lougee’s. He’s recovering from knee surgery, and besides, the invitation to ride came from Pete Essaf who, with passenger Kenny Harrold, won both the AMA and the AFM sidecar championships in 1980. It was the second year on top for Essaf, who passengered with driver Gary Gipe on the same sidecar to win the same two championships in 1978.

Essaf’s sidecar (or outfit, or chair, or rig, or sidehack, or hack, or bike, all being terms used by sidecarists for their machinery), started life as an English MGF chassis built in 1968 to accept a Triumph Trident engine. When Essaf bought the chassis in 1977, it had a Kawasaki Z-l engine. After three club races with Gipe, Essaf extensively modified the chassis, changing it from a front-exit to a rear-exit chair.

Essaf s chassis has its third wheel to the left of the front and rear wheels. Originally, the passenger hung off in front of the third wheel (hence, front-exit) for lefthand turns and leaned behind the driver for righthand turns. By changing handholds and the platform (the place where the passenger kneels when not hanging off), and by installing a knee cup outside the third wheel, Essaf made it so the passenger hung off behind the chair wheel in lefthand turns. That reduced the distance the passenger had to travel between righthand and lefthand turns, which reduced the time in transition, which made it possible for the sidecar to careen up a set of ess turns at a higher rate of speed.

When he installed the knee-cup outside the chair wheel, Essaf added a second axle support, outside the wheel, to handle the extra weight placed on that point by the hanging-off passenger. He also switched the chassis from the original 10-in. MiniCooper wheels to 13-in. Formula Ford wheels. With larger wheels, Essaf could use Goodyear Blue-Streak slicks developed for racecars, as well as fit larger 10in. Kosman brake discs. Two discs are used on the front wheel, one each on the rear and chair wheels.

Essaf raced and modified his sidecar further, welding in bracing here and there, changing head angle, building a fiberglass fairing, adding an aluminum belly pan. As it sits now, his sidecar is more Pete Essaf than MGF, terribly cobby from constant modifications, typical in this class of buildit-yourself racing machines.

Essaf’s sidecar weighs 620 lb. with gas,( which is carried in a flat tank underneath the platform and fed to the carburetors b>v a fuel pump, with a pressure regulator built into the system. Wheelbase is 56.5 in. from the center of the front axle to the rear wheel axle. The rear wheel is not di* rectly behind the front wheel, but is set 2 in. toward the center. The chair wheel is" 40.5 in. to the left and 12.5 in. ahead of the4 rear wheel.

Front suspension is leading link, using two conventional motorcycle shock absorbers. Two more shocks are used on the rear-wheel swing arm, and the chair wheel is, by rule, rigid. Front and rear wheel travel is 1.5 in. The highest point on the sidecar is the top of the fairing bubble, 30^ in. above the pavement.

Essaf’s engine is relatively mild; 1015cc using Yoshimura pistons, Engl^ cams, a custom exhaust system and 31 mm Keihin CR carburetors.

“Ground effects are very important on a sidecar,” says Essaf, pointing at his rig’s" fairing. “This fairing is very ground effective. It holds the bike down well because it has a large surface area that is like ar^ airfoil. The underneath of the sidecar is covered by an aluminum skin which also helps hold the chair down. The name of the game is holding the chair on thej ground so you can go around the turns. Once the chair starts coming up into the air you have to roll off the gas or, if the turn’s slow enough, gas it very hard and break the rear wheel loose. The chair will only come into the air when there is traction on the front and rear wheels. If the ^driver can break the rear wheel loose and put the rig into a slide, the chair will come down.

“Learning to race one of these things is really strange because it’s not like a twowheeler and it’s not like a four-wheeler. You can’t take anything you learn from driving a car or a motorcycle and use it on one of these. You have to learn all over again. Going into a lefthand turn it handles one way, and going into a righthand turn it handles another way. It’s like driving two different vehicles.

“Sidecar racing is a team sport,” Essaf tells me. “When I’m driving, I’m concentrating 90 percent on what I’m doing and 10 percent on where the passenger is. You have to think about the passenger. You can’t concentrate 100 percent on your driving, and that obviously hinders your driving at full speed.

“Most people think it’s the passenger who’s in danger,” Essaf continues. “But when you’re a driver crouched with your legs held by knee cups with handholds across your thighs, you can’t get out quickly, so you’re going to be on the bike until the end, wherever it ends up. If your passenger makes a mistake, he’s going to fall off. But the driver cannot get off the sidecar, and that fact is always in the “driver’s mind.

“So the driver has to pay attention to what the passenger is doing. Is he in the right place? Can I turn the gas on now? If I hit the brakes too hard while his hand is between hand holds, will that make him miss the handhold completely and fall off? The driver has to be constantly smooth and very consistent in braking points and acceleration points so the passenger can learn exactly how he drives a track. The passenger has to make his move when it’s easiest for him. If he knows when I’m going to put the brakes on, he starts moving before I put the brakes on, so he’s in a position where the braking force doesn’t affect his motion.

“That’s all part of being a very precise team. Precision as a team is what makes the bike go around the track fast. You can have a very fast driver and have a very good passenger, but if they aren’t working well together, aren’t meshed, then they aren’t going to go fast.”

I stare at the sidecar, noting a loop of tubing in front of the outboard knee cup, and ask Essaf what it’s for.

“It’s a nerf bar,” he says, “so the passenger doesn’t get squashed when we get "close to another rig. When you’re going really fast you have to stick pretty much to the right line. And since the outfit is so wide, and the other outfits are so wide, sometimes in order to get around somebody you’re six or eight feet off the proper solo line. Plus often the driver in front will use his width to his advantage. He’ll leave four feet on the inside of the track, which is not enough for another sidecar to squeeze through, but which puts him far enough out on the line that if I try to go around the outside, I’ll be totally out of position and off the line. That’s where a lot of strategy comes into play. And a lot of close driving, so we have the nerf bar to protect the passenger.”

Essaf kneels on the platform and runs through the positions taken by the passenger for turns and straights, showing me where to hold on and how to switch hands from handhold to handhold and move to change position without ever letting completely go.

“You can approach being a passenger on a sidecar in two ways,” Essaf tells me. “You can muscle it, or you can let the sidecar help you. In a learning stage you always clamp on a lot tighter than you need to. You always try to move a little sooner than you should or a little later than you should. The ideal transition happens when the bike is switching its own position on the racetrack. When you’re going through ess turns, you don’t wait until you’re through the first part of the turn before you start moving into position for (he next part. You actually start moving as the bike is exiting, when the bike is coming to you.”

Essaf points to his voluptuous girlfriend, Adrian, a long-legged and slim 115 lb. on a 5 ft. 10 in. frame. “Adrian is not a muscular person and she passengers very well,” Essaf says. “She uses the bike’s momentum, and that’s the secret to becoming a really good passenger. You have to learn that the bike will move underneath you if you let it, if you move as the bike is moving. It just kind of flows.”

“I let the G forces help me,” says Adrian, “because I can’t muscle my way around. Sometimes if I’m late making a move it’s really hard to get into position, and sometimes it’s impossible. I had to get my timing down, to know when to move.”

Adrian looks as if she belongs on a stage modeling long, flowing evening gowns for a Paris designer, blonde hair reaching her waist, a smile a permanent reflection of her sunny disposition. It was impossible to reconcile stories I had heard about the difficulty of being a passenger on a sidecar with the image of beauty standing before me.

“My sidecar is the most difficult competitive sidecar to passenger on,” says Essaf, continuing. “My bike weighs more than most bikes, and in order to make it maneuver around the turns at the same speed as the lighter bikes, the passenger has to move his weight farther. That’s why we have the knee cup outside the chair wheel, as well as a footpeg outside the rear wheel, so the passenger can straddle the rear wheel in righthand turns.

“Sears Point is the most demanding track you’ll find for a sidecar. It’s very bumpy and twisty and if you can figure your way around this track fast it’s easy to go to any track and go fast.”

Essaf asks me if I’m ready to try it. I nod, buckle my helmet and help bumpstart the engine. Suddenly we’re on the track and heading for the first turn, a wide-open-in-top-gear uphill left sprinkled with bumps and ruts (yes, ruts, in asphalt!) and topped by an off-camber right leading downhill to a left at the bottom that connects immediately to a short uphill with an off-camber right at its crest.

Before we reach the first left I’m struggling to remember where to put my hands and to shift my left leg over the sidecar wheel into the knee cup, following with my body hanging off the side. Each bump pounds the chair fender into my chest and jerks at my extended right arm, the link holding my horizontal body to the swaying, bouncing sidecar. Too soon the car jerks right and I struggle back onto the platform, pulling with all my might, diving over the rear wheel fender across Essaf s back, feet scrambling for toeholds and arms locked into position and then Eve got to move back for the hill-bottom left and the force flings me out too fast, my right hand almost torn away and that topof-the-hill right follows and I almost fall off reaching up from hanging-off-left to over-the-rear-fender right.

It’s hang on for dear life as Essaf accelerates downhill over more huge bumps to a tight, still-downhill right that leads to a sweeping uphill right where the track crests and spills away downhill in the Sears Point carousel, with a dip at the bottom and a short, hooked straight leading into a u-turn that marks the start of the fast esses, left-right, left-right-left-right in a mix of radii, the series leading into another u-turn and another hook-left straight, across the start/finish line up the hill again.

The course runs through my mind but Essaf and I are still approaching the crest before the carousel. The bike gets light over the top and I dive again for the lefthand position, leaning way, way out and immediately realize that the horizon’s gone mad, my helmet is skimming the pavement and bumps. Track curbs and apex alligator bumps look entirely different when it’s your head that might smack them, not your knee.

The horizon tilts and weaves as Essaf accelerates and the sidecar crosses the dip at the carousel exit, and I can feel the rig slewing just a bit sideways, the power working against tire traction. I’m still outboard entering the straight and when I realize I’m supposed to be back up on the platform and pull myself in, the hack turns right and weaves back straight again, Essaf correcting for my too-sudden, poorly-timed return.

And then he’s braking, hard, for the uturn entrance to the esses, and I’m leaning left for the first, shallow ess turn and leaning right for the next, then climbing off for the next left and struggling back aboard for the critical right that follows, downhill across huge bumps, hanging off again for a left and scrambling upright, again, for the right* against incredible forces even though Essaf feathers the throttle, waiting for me to make my move before he drives into the fast right. Straight, brakes, u-turn right, accelerate straight, climb out for the top-gear left, pull, pull, pulling and eyes inches from the pavement, the hill distorted by viewpoint, then the red-andwhite striped curb on the left that Essaf told me meant the start of the off-camber right, my right arm refusing to pull me aboard quickly. My move is late. Essaf pitches the rig right and momentum yanks, holding me outside, momentarily keeping me from climbing safely aboard, into position. All that holds me on is the knee cup, letting me brace my leg against the powerful, invisible hand that tries to flip me off onto the ground. Somehow I make it, huffing and panting and weak in the arms, and try for the position for the left and the track goes on and on and my moves get slower and slower until I pound Essaf on the back and he slows, cruising back into the pits where I climb off and sit against the wall, guzzling Gatorade and sweating and listening to my heart roar in my ears, wondering.

I just can’t believe it. Through my mind I work the memories of scary things I’ve done and riding a nitro-burning fueler at the drags jumps to center stage and stays there.

Yeah, riding a fueler is more scary, but riding a sidecar as a passenger is the hardest, most foreign thing in asphalt racing, and the second-scariest. The amount of force and muscle it takes to hold on and move just doesn’t relate to anything else.

To watch Adrian, lovely Adrian, passenger puts it in perspective. I have trouble transferring from left to right, don’t know what I’m doing, worry about being in the wrong place at the wrong time. She dances over the chair, left, neutral, jumping over the rear wheel and balancing on the extra footpeg outside the wheel, jumping back to neutral and then full hang-offleft, doing it with a fluid grace and ease that is not possible.

Essaf comes over and tells me that when he first started passengering, his right arm pumped up so much from the strain that his leathers wouldn’t fit, that he had to have the right sleeve enlarged. I pull my arms from the sleeves of my leath-“ ers and stare at my forearms, the right one visibly larger and throbbing, veins popping out with each heartbeat.

The key, says Essaf, again, is letting the forces work for you, not against you, making your moves when the car is pitching toward you, not away from you. He lists^ landmarks to watch for on the track, places to make transitions. And he shows me how he holds on with thumb and fingers all on top of the handholds, not with the thumb wrapped around, because his way doesn’t waste any strength gripping and makes transitions faster.

“The faster you go the easier it is because the chair comes to you, whips from one side to the other,” says Essaf. “In the transition it actually comes up to where you are, so you don’t have to reach for it so much. We were doing 2:25s, and race speeds are 2:08 and faster. This time we’ll^ speed up a little.”

He does. And it does get easier. The sidecar lurches violently at the top of the hill and comes toward me. All it takes is coordination of moves with the action of the sidecar. Yeah. Just that simple. Yet so hard.

My arm still pumps up, and it’s stillH strange and impossible, but the number of laps I can go increases, and Essaf keeps bringing up the speed. Three laps this time. Four laps the next. Five the next. It’s more familiar, but still difficult. A typical AFM sidecar race is six laps at Sears, and I almost have an idea of where to be and when to move, and I figure I’m a sidecar passenger. The time’s come down to 2:14/ which Essaf says is a great time for a beginning passenger at Sears, and this time we’ll go six laps at that speed, maybe faster.

It was during a transition between a lefthand ess and a righthand ess turn. I -still wasn’t used to the quick up-and-down jolts of the barely-suspended hack on the rough, potholed pavement. I was pulling my leg back onto the platform, straddling the side wheel fender, when the outfit hit a lump in the tarmac and the chair wheel jumped into the air. The pain was quick and total. I fell back into the hang-out-left position, unable to pull and barely able to hold on. All I could do was punch Essaf >once on the back as he snaked the rig into the right, my counterweight all wrong for the turn. He hit the brakes and drove slowly into the pits, and stopped. I rolled onto the ground on my back, stared at the sky, and wished Adrian was not looking into my helmet with concern on her face.

“Do you want to try driving it now?” asked Essaf, much later. I knelt in the driver’s position, a curved handhold circling tight across my left thigh. A cage on the shift lever gripped the toe of my left boot, and my head filled with a story I had heard about this outfit.

Kerry Bryant was racing Superbikes when Essaf asked him to try driving the sidecar. Bryant and Essaf finished third at Bryant’s first club race with the sidecar, then won another eight AFM events in a row. The pair led the 1979 Sears Point AMA National sidecar race until the engine broke, and were leading at Laguna Seca the same year when Essaf fell off in sweeping turn three at more than 100 mph. Out of control, Bryant ran off the track, tried to bail out and couldn’t and was caught underneath when the sidecar flipped. Video tape of the crash shows Essaf running to the sidecar, peering through a cloud of dust at Bryant’s inert form, and then flinging himself on the ground in remorse and frustration.

Bryant, although shaken and bruised, escaped serious injury and drove one more time, at Pocono. There, Essaf fell off again. It was Bryant’s last sidecar race.

“Being a solo rider I felt I had my job to do,” Bryant told me the day before I joined Essaf at Sears. “I was in control and I never even thought about the passenger. It was easy for me to beat all the top drivers in sidecar racing at the time, turning faster lap times and just laughing in my helmet the whole time. I concentrated on what I was doing, driving it like a solo, working on late braking and fast entrances to the turns. Maybe that’s why I was able to go faster. The problem is that with a sidecar, if the passenger falls off, you crash. Most of the sidecars have so many handhold bars going across the driver’s legs and hips that when you’re in there, you can’t get out. So if the passenger falls off, the driver’s lucky to survive. There is just no way to get out of the rig, and if it’s going to flip over, you’re going to be underneath it. If it’s going to crash into Armco, you’re going to be aboard when it hits.

“So the sidecar driver has to think about the passenger as well, pay attention to where he’s going and make sure he’s there on time. You have to really trust your passenger. Here I had Pete Essaf, the best passenger in sidecar racing, and I spit him off at Laguna. Then he talked me into trying it again, at Pocono. I had no problem turning the fastest lap times, but what happened again was that with my solotype lines I changed direction more suddenly than other sidecar drivers, and I spit him off in the chicane. Then, again not thinking about him, I went around the banking, down the front straight, through turn one and started to go into turn two without knowing he was gone. The chair wheel came up three feet off the ground, the exhaust pipe dragging on the track. I just barely saved it, I don’t know how.

“Him falling off again shook me up. I got scared. It went from being a real fun thing to do, a real laugh, to just being scary. I worried that if he fell off in another turn I could die. I can go as fast as I want on the solo bike, and only have to worry about what I’m doing. I love to ride any kind of bike. But with a sidecar, trusting the other guy is too much. I just lost all my nerve. Most times, there’s no way to save it if the passenger falls off. You just barely turn the handlebars without a passenger and the chair comes up, right now!

“I can’t do it anymore, because of Pocono ...”

Bryant’s words echoed in my head. “No,” I tell Essaf, shamed that something in motorcycling has finally called my bluff. “I definitely do not want to drive it.”

If Essafs sidecar is typical of machines making up the class in America, then Mark Bevins’ outfit is atypical. It’s also a harbinger of things to come.

Bevins, a passenger, bought a complete MGF chassis with a TZ700 engine in 1978, and enlisted Larry Coleman as driver. Coleman had driven his own GT750-powered outfit to the AMA championship in 1976 and 1977, then retired in horror at the cost of racing. Bevins enticed Coleman out of retirement by promising to pay all expenses then, with the help of friend and mechanic Mark Herren, extensively modified the MGF between the 1978 and 1979 seasons. Bevins, a tool-anddie maker, committed his entire salary to the race effort, living off his wife’s earnings.

Even as Bevins and Coleman were winning the 1979 AMA championship and attracting sponsorship help from Kal-Gard (a lubricants and coatings manufacturer), they and Herren were aware of the limits of their machine. Herren, a machinist who had taken high-school drafting courses, designed a new frame based on what he saw of European sidecars in British magazines, personal experience, and expert ments with the MGF. Then, at night and on weekends over a period of four months, Herren and Bevins built a chassis.

The main structure is all straight pieces of 2-in. o.d. chrome-moly tubing with0.062 in. wall thickness, each piece handfitted and welded to adjoining members* The frame runs under the engine and up to the steering head, and a single 3/4-in. o.d. tube runs back from the steering head to behind the stock TZ750 engine, bracing the steering head under hard braking.* Each 13-in. Formula Ford magnesium wheel is supported on one side. A single» leading link is used in the front, a singlesided swing arm in the rear. Wheel travel is 1.5 in. front and rear. The chair wheel is unsuspended per the class rules.

The brakes are 10.5-in. discs, one on^ each wheel, with a double-acting, fourpiston Edco sprint car caliper on the front* and double-acting, two-piston Edco calipers on the rear and chair wheel discs.

Wheelbase is 57.75 in. The chair wheel is 13 in. ahead of the rear wheel and 44 in. to the left. The front wheel is offset toward the center of the rig, 3.0 in. to the left of the rear wheel, and the engine is further offset 2.75 in. to the left of the front wheel, for reasons to be explained shortly. The-* complete outfit weighs 460 lb. full of gas and has an overall height of 24. in.

“Any sidecar is basically an unstable vehicle,” Herren tells me as we stand iif the Sears Point pits, two weeks after I rode Essaf’s outfit. “Compromise is the big thing. You have to make adjustments in the right hand cornering to make it handle better in the lefts, and vice versa. This one does handle relatively equally, but it’s still a lopsided vehicle no matter how you look at it. All you can do is try to keep that to a minimum, which is the reason for the en-’' gine and wheel offset. The closer you can make the sidecar to being a tricycle, the" more evenly it’s going to handle. The chassis was designed with the idea of keeping all the weight down below the axles and as close together as possible. That’s why all the chassis strength is down low and not over the motor. We didn’t even have the bar over the engine at first. That bar is"1 there only because the steering neck pulls forward slightly under braking. We installed the bar so we could use more of the^ available braking power.”

The fuel tank is located ahead of the platform, Bevins says, to hold platform height down and keep everything out of-» The passenger’s way. A fuel pump delivers gasoline to a large diameter alloy tube over the carbs, that tube being fitted with ^return lines and feed lines to the carburetors. The tube serves the same function as a still airbox, in Coleman’s words, “kind of fooling the carburetors into thinking they don’t have any pressure on them. The carburetors are in essence being fed fuel only by normal gravity pressure.”

I kneel on the rear-exit platform and “notice at once that it flexes with my weight. “I allowed this thing to flex in places where other sidecars are rigid,” explained Herren. “I tied the wheels together and tied them to the engine so the horsepower and braking force can go through the engine and wheels, and whatever the rest of the chassis does doesn’t really matter as long as all the wheels stay in their position.”

The tires mounted on those wheels look iïuge, and are. The tread surface is 7.0 in. on the front and chair wheels, 9.0 in. on the rear wheel. “The front and chair ►wheels are Formula Ford tires and the rear was designed for sedan racing,” says Bevins.

“Yeah, the rear wheel has a harder compound and a different design,” says Coleman. “If the chair comes up in the back or if the back squats excessively, the rear tire Lwe use will accept more camber change— 3°—than Formula Ford tires, which accept very little camber change—1.5°.”

“The rules don’t allow the chair wheel to be suspended,” continues Herren. “So, no matter what we do, we have to put up ^vith some camber change. One of the problems first encountered when sidecars went to car racing slicks is that they don’t kwork if they’re rolled up on the edge. They can only accept so many degrees of camber change, and since sidecars have suspension on only one side, they tilt and ►change the wheel camber. We even designed into the suspension somewhat to compensate for that in the rear.”

“We can adjust initial camber with the sway bars,” adds Bevins, “And that adjustment will stay the same throughout the suspension travel.”

> The attention Herren, Bevins and Coleman pay to camber is understandable. They learned the hard way. Because the trio thought soft suspension was the key to “a plush and fast ride around Sears Point, the just-completed sidecar started its first practice run with 2.0 in. front wheel travel >and 2.5 in. in the rear. The shocks had very light rebound and compression damping to match light springs. Compounding the error was too much camber on the wheels, K2.5 ° on the front, 2.0 ° on the chair, and 5 ° on the rear wheel. The result was a horrendous end-over-end crash in one of the ^fastest turns on the course. A long, slow process of figuring out what caused the crash, rebuilding the outfit, and dialing in the chassis followed. Finally finished and "sorted out, the sidecar carried Coleman> and Bevins to victory in an invitational sidecar race held at the Long Beach Formula One Grand Prix earlier this year.

“This sidecar is much easier to passenger than Essafs,” Bevins says as he shows me the hand holds. But I note at once that Bevins uses fewer handholds than Essaf, and what handholds he does have are spaced farther apart. There are no handholds blocking Coleman’s legs, so he can eject in a crash (and did, in the outfit’s inaugural accident). Bevins relies heavily on loops of tubing at the rear of the platform, which he braces his feet against. When he leans out for left turns, Bevins wraps his chest around the chair wheel and hooks his left hand into the radiator scoop in front of the fiberglass fender. It’s harder to hold the outboard position because there is no knee cup outside the wheel, but because the passenger doesn’t have to move his leg over the chair wheel fender, he should be able to get into position more quickly than the passenger on Essafs outfit.

Confident from my laps with Essaf, I set off down the track with Coleman. The first few laps were no problem, but as Coleman picked up the pace it was obvious that this lighter sidecar is more affected by where the passenger is and what he does, changes direction more quickly and more violently, stops harder and in general is more difficult to hang onto.

It makes power, lifting the front wheel exiting slower turns and sliding around some lefts as Coleman gasses it when he’s sure I’m in position.

A car driving school was using the Sears Point track that day, and the front straight was partially blocked with lanes of traffic cones. Coleman couldn’t accelerate hard from the last turn, down the straight and into the first turn in top gear. Instead he had to maneuver left around the cones blocking the straight, then head up the hill out of position and at a greatly reduced speed.

But the bumps heading up the hill still pounded my body and made the transition from left to right at the crest difficult or impossible if not timed correctly. It was while still hanging out left one lap that I looked straight forward and saw two exhaust pipes spitting out a light, oily haze 18 in. ahead of my face. But the transition from left to right that followed was for some reason perfect, the chair swinging over to meet me, and when I hooked my right arm and chest over the rear wheel, T looked forward again—and saw the throttle slides working in the carburetors.

When Coleman picked up the pace, my confidence as a passenger shattered. If suddenly became quite clear that when I couldn’t see throttle slides in the carbs from the righthand position, when the carburetors were constantly on the main jets, I was barely able to hang on, let alone move in time for the turns. And when, on one lap, Coleman dove into the last u-turrr at racing speed, applying the brakes with the same force as he does every lap in competition, my body rolled partway up his back in spite of my best efforts to brace myself.

The lap that followed was fast, hectic, draining, ending when I completely blew the transition entering a left, arriving way too late and way too suddenly, Coleman wrestling the bars as the sidecar slew side to side and threatened—I thought anÿ*way—to roll or spin or flip or all of the above. He pitted then, and I was glad.

We had turned a 2:16 with the fastest, part of the course blocked off, Bevins told me. We had reached racing speeds in a few corners, Coleman added, listing the carousel and the final, hard-braking turn. ->

I had new respect for sidecar racers, both drivers and passengers, I told them. It’s harder than it looks, and scarier.

Surely, they are brave men, and brave" women. 13

View Full Issue

View Full Issue