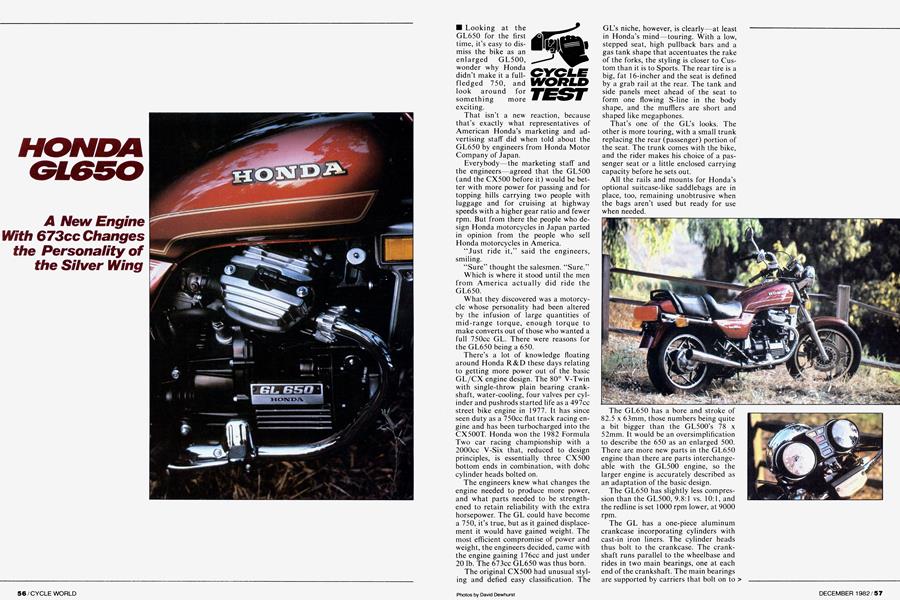

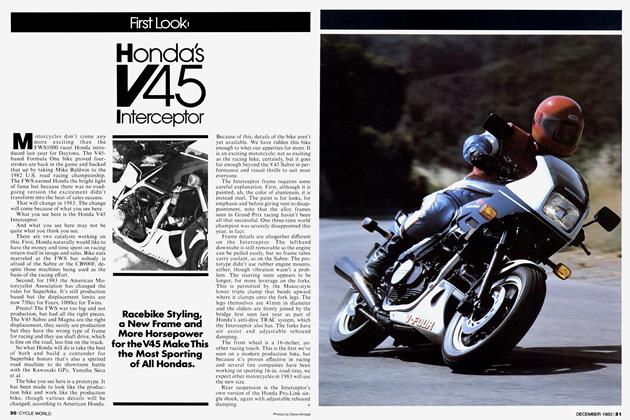

HONDA GL650

A New Engine With 673cc Changes the Personality of the Silver Wing

CYCLE WORLD TEST

■ Looking at the GL650 for the first time, it’s easy to dismiss the bike as an enlarged GL500, wonder why Honda didn’t make it a fullfledged 750, and look around for something more exciting.

reaction, because representatives of

That isn’t a new that’s exactly what American Honda’s marketing and advertising staff did when told about the GL650 by engineers from Honda Motor Company of Japan.

Everybody—the marketing staff and the engineers—agreed that the GL500 (and the CX500 before it) would be better with more power for passing and for topping hills carrying two people with luggage and for cruising at highway speeds with a higher gear ratio and fewer rpm. But from there the people who design Honda motorcycles in Japan parted in opinion from the people who sell Honda motorcycles in America.

“Just ride it,” said the engineers, smiling.

“Sure” thought the salesmen. “Sure.”

Which is where it stood until the men from America actually did ride the GL650.

What they discovered was a motorcycle whose personality had been altered by the infusion of large quantities of mid-range torque, enough torque to make converts out of those who wanted a full 750cc GL. There were reasons for the GL650 being a 650.

There’s a lot of knowledge floating around Honda R&D these days relating to getting more power out of the basic GL/CX engine design. The 80° V-Twin with single-throw plain bearing crankshaft, water-cooling, four valves per cylinder and pushrods started life as a 497cc street bike engine in 1977. It has since seen duty as a 750cc flat track racing engine and has been turbocharged into the CX500T. Honda won the 1982 Formula Two car racing championship with a 2000cc V-Six that, reduced to design principles, is essentially three CX500 bottom ends in combination, with dohc cylinder heads bolted on.

The engineers knew what changes the engine needed to produce more power, and what parts needed to be strengthened to retain reliability with the extra horsepower. The GL could have become a 750, it’s true, but as it gained displacement it would have gained weight. The most efficient compromise of power and weight, the engineers decided, came with the engine gaining 176cc and just under 20 lb. The 673cc GL650 was thus born.

The original CX500 had unusual styling and defied easy classification. The

GL’s niche, however, is clearly—at least in Honda’s mind—touring. With a low, stepped seat, high pullback bars and a gas tank shape that accentuates the rake of the forks, the styling is closer to Custom than it is to Sports. The rear tire is a big, fat 16-incher and the seat is defined by a grab rail at the rear. The tank and side panels meet ahead of the seat to form one flowing S-line in the body shape, and the mufflers are short and shaped like megaphones.

That’s one of the GL’s looks. The other is more touring, with a small trunk replacing the rear (passenger) portion of the seat. The trunk comes with the bike, and the rider makes his choice of a passenger seat or a little enclosed carrying capacity before he sets out.

All the rails and mounts for Honda’s optional suitcase-like saddlebags are in place, too, remaining unobtrusive when the bags aren’t used but ready for use when needed.

The GL650 has a bore and stroke of 82.5 x 63mm, those numbers being quite a bit bigger than the GL500’s 78 x 52mm. It would be an oversimplification to describe the 650 as an enlarged 500. There are more new parts in the GL650 engine than there are parts interchangeable with the GL500 engine, so the larger engine is accurately described as an adaptation of the basic design.

The GL650 has slightly less compression than the GL500, 9.8:1 vs. 10:1, and the redline is set 1000 rpm lower, at 9000 rpm.

The GL has a one-piece aluminum crankcase incorporating cylinders with cast-in iron liners. The cylinder heads thus bolt to the crankcase. The crankshaft runs parallel to the wheelbase and rides in two main bearings, one at each end of the crankshaft. The main bearings are supported by carriers that bolt on to > the crankcase, one carrier at each end. The five-speed transmission runs parallel to the crankshaft and is located underneath and to the right of the crank, again supported at the ends by bearings held by bolt-on carriers. The wet clutch is mounted at the front of the engine, on the mainshaft, and is driven by a gear bolted to the end of the crankshaft. The transmission countershaft is splined and fits directly into the end of the driveshaft.

The transmission turns in the opposite direction from the crankshaft, and in doing so, offsets the torque reaction common in motorcycles with crankshafts running fore to aft. Blip the GL’s throttle in neutral at a stop and the bike tries to lean right a classic reaction. But when the motorcycle is moving, the transmission is spinning, so blipping the throttle has no such effect.

The camshaft is located above the crankshaft, between the cylinders, is driven by a link-plate chain off the crank, and operates the valves through followers, pushrods and forked rocker arms with adjustable screw tappets. The cam chain has an automatic tensioner like the CX500T Turbo engine but unlike the GL500, which had manual cam chain tensioning.

The alternator is attached to the rear of the crankshaft, and the electronic ignition pickups take their pulse signals off the alternator rotor. The water pump is located above the alternator and is driven off the rear of the camshaft.

Those basic design details—except for the automatic cam chain tensioner—are common to the GL500 and GL650 engines. But the list of altered specifications designed to deal with the 650’s increased power output is long and varied. To start with, the GL650 has a different crankcase casting, not only to accommodate the larger cylinder liners and longer stroke, but also to add a bolt-on, finned sump pan which increases oil capacity and cooling. The oil pump pickup is lengthened to reach into the sump pan, and the pump itself has a thicker rotor (from 12mm to 15mm) to increase pumping volume.

The crankshaft is made from a higher grade material and matches the longer stroke. It also has larger journal diameters, main bearing journals increased 3.0mm from 43mm to 46mm, and the connecting rod journal increased 3.0mm, from 40mm to 43mm o.d.

The connecting rods are also made of better material, exact composition unrevealed for reasons better explained by Honda, and are longer to suit the new stroke. Rod bolts are 9mm instead of 8mm and rod bolt thread pitch is up from 53 threads per inch to 56 threads per inch.

The cylinder heads are still rotated 22° from the crankshaft centerline to position the two Keihin CV carburetors inboard of the rider’s knees, but the cylinder head ports have been straightened to improve flow, and the airbox is larger. The intake valves are larger, gaining 1mm in diameter, from 31mm to 32mm, and there’s more valve lift and duration. The GL500 engine lifted both intake and exhaust valves 7.0mm, while intake valves in the GL650 engine are lifted 7.8mm and exhaust valves are lifted 8.0mm. The GL650’s valves are kept open longer, intakes opening 7° BTDC and closing 53° ABDC, exhausts opening 40° BBDC and closing 15° AT DC. The GL500’s intake valves were timed at 6-46, exhaust valves 46 6.

The ignition system has new pulse generators and coils designed to fire spark plugs with a larger, 0.035-in. gap compared to the GL500’s 0.028-in. gap.

The transmission gears are all wider to handle the extra power, the increase ranging from 2.0mm wider to 6.8mm depending upon the gear and the load it carries. The transmission gear ratios are new, every one being taller to reduce rpm, and the primary reduction ratio is taller as well with two more teeth added to the crankshaft primary gear and two teeth removed from the clutch gear.

The shift forks are forged and have a higher chrome-moly content than the welded forks and chrome-plated fork tips of the GL500, and the shift fork shaft and shift drum have been redesigned to match the wider transmission gears.

The clutch has six drive plates, one more than the GL500’s clutch. The clutch basket is deeper to accommodate the extra plate, and the clutch springs are stronger to handle the extra power.

The 650 has a larger radiator, a new water pump impeller and an electric, radiator-mounted fan replacing the camshaft-driven fan of the GL500.

There have been changes to the frame to deal with the extra power. The GL650’s engine hangs from the frame there are no frame members underneath the engine and now the front engine hangers are cast iron vs. the GL500’s stamped steel, making the connection between engine and chassis more rigid. The top frame tubes are 3.2mm larger in o.d. and wall thickness has been increased from 0.7mm to 1.1mm depending upon the individual tube’s location. The front forks have 37mm stanchion tubes (the GL500 forks were 35mm), and a brace bolts between the stanchion tubes, above the front fender.

The rear axle is larger, up from 15mm to 17mm, and the rear rim size is up from 2.50-16 to 3.00-16. The rear tire now carries an H speed rating instead of the GL500’s S rating. The wheels are cast aluminum alloy, replacing the 500’s bolttogether ComStars.

The front wheel carries two disc brakes instead of the GL500’s single front disc, and the discs are larger, up from 240mm to 276mm. The discs don’t ride on carriers but bolt directly to the enlarged hub of the cast wheel, making the disc assembly more rigid and less prone to warping.

The rear brake is a rod-actuated drum.

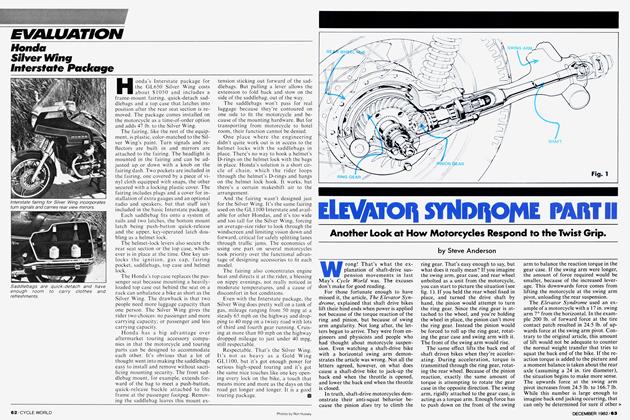

The forks run both coil springs and air pressure, as did the GL500’s forks, but the minimum air pressure has been reduced and a short preload spring replaces the preload spacer of the 500, both changes designed to increase compliance. The rear suspension uses a single large shock absorber and Honda’s ProLink rocker system to connect the shock to the swing arm. Like the forks, the rear shock has both a coil spring and adjustable air pressure, and the Pro-Link rocker system is designed to produce a progressive increase in spring rate as the shock is compressed.

All the changes make the GL650 19 lb. heavier than the GL500. That figure might have been greater. The exhaust system is actually lighter on the GL650, thanks to the use of tubing with 0.4mm less wall thickness and a new exhaust pre-chamber—an expansion box between the exhaust headers— construction.

The GL650 has a higher GVWR than the GL500, but the 16 lb. of extra carrying capacity is used up by the extra weight of the motorcycle.

That’s a small matter. What really impresses about the GL650 is that this is a different motorcycle than the GL500 or the CX500 before it.

The most noticeable difference is the power. The GL650 is much quicker and faster, turning the quarter mile in 12.93 sec. with a terminal speed of 100.5 mph compared to the GL500’s 14.01 sec. and 91.09 mph. The GL650 reaches 107 mph in a half mile, vs. the GL500’s even 100 mph.

And where the GL500 demanded revs—lots of revs—to move briskly down the highway or to pass traffic, the GL650 will do all that and never need more than 5000 rpm. If the rider is so inclined, the GL650 will happily chug through town traffic below 4000 rpm, all the time emitting that wonderful offbeat V-Twin cadence through louder-than-average mufflers.

With the taller gearing, the GL650 turns 4500 rpm at 60 mph—the GL500 turned 5300 rpm at the same speed—and gets 56 mpg on the Cycle World mileage test loop—the GL500 returned 53 mpg—despite the extra power.

If there’s a price to be paid for the 650’s increase in power, it is in engine smoothness, or rather, in the lack of engine smoothness. The 650 transmits distinct power pulses to the rider, especially through the handlebars, and at 60 or 65 mph it vibrates enough to annoy some riders used to silky-smooth, rubbermounted Fours. Compared to a vertical Twin without counterbalancers, the GL is a smooth motorcycle. Compared to a Four or a Ducati V-Twin, the GL is not.

That the GL650 vibrates more than the Ducati Pantah 600, for example, is likely because Ducati prefers 90° Vees, a configuration which produces perfect primary balance. Honda, on the other hand, chose 80° as a compromise between smoothness and compactness.

Overall staff reaction to the GL650 engine was favorable, the sound and feel of the power pulses gaining more favor than the vibration through the bars gained disfavor.

Changes to the suspension have improved small-bump compliance all around, and the GL was pretty good before. This motorcycle has comfortable suspension, and the air adjustability works well to tailor the ride height and firmness to the weight of the rider or riders and any luggage.

The same suspension suppleness works against the bike in hard and fast riding, and pitching the GL650 into fast turns, making rapid S-turn transitions or even exiting one turn and hitting the brakes hard for the entrance to another while > still leaned over will send the bike into short-lived undulations. Increasing air pressure at both ends ensures that the problem won’t surface on the street with any responsible and reasonably-sane rider.

Everybody who rode the GL650 liked the controls and simple instruments (including 130-mph speedometer) and lights and extremely-loud, wonderfullypiercing set of dual horns mounted on the lower triple clamp so every sound wave breaks directly into the ear of offending motorists.

The seating position is less pleasing. The trend in motorcycling seems to be away from stepped seats/high bars/forward footpegs and for good reason—at speed on the road the seating position produced by the combination isn’t the most comfortable for most riders. Loud and long were complaints that the GL650 would make a perfect sports bike—it is, after all, faster than a Pantah—if only the engine came in a sporting package.

It isn’t that the seat is hard or poorly shaped; Honda’s engineers seem to have done their homework on every part of the machine, and the seat is actually comfortable. The problem comes in the lack of choice of position forced upon the rider by the combined placement of bars/pegs/seat.

The whole arrangement makes better sense when the rider isn’t leaning into the wind, instead riding behind a windscreen and fairing. For more on that, see the evaluation of the GL650 Interstate in this issue.

So what of the GL650? It is enough better than the GL500 in terms of performance—both ultimate and everyday—to make it appealing to motorcyclists who would never have swung a leg over the GL500. Riders who appreciate the GL’s engine more than its styling and touring bias lament that there isn’t another, more sporting version, but for anybody who likes the GL’s looks, and wants water cooling and shaft drive, the bike is hard to beat with 650cc. SI

HONDA

GL650

View Full Issue

View Full Issue