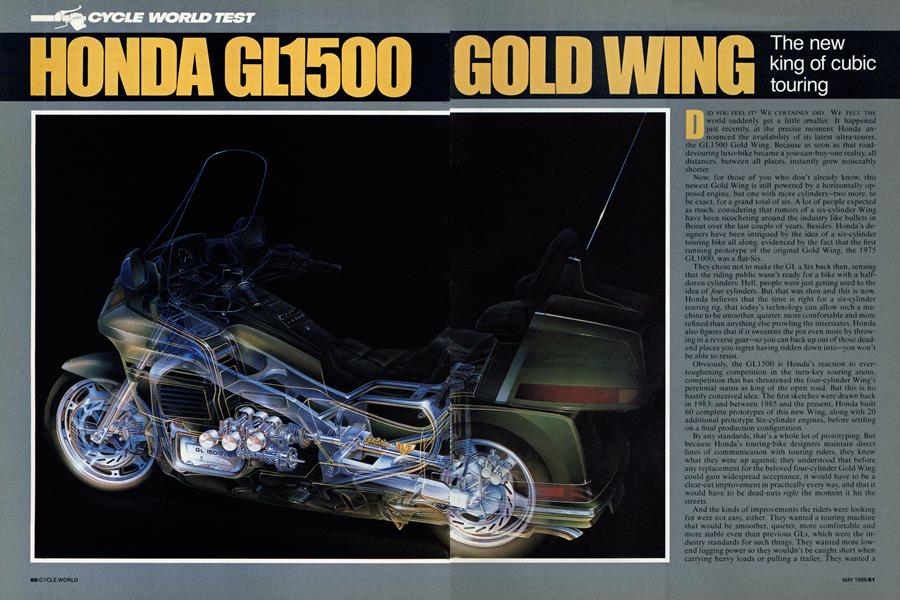

HONDA GL1500 GOLD WING

CYCLE WORLD TEST

The new king of cubic touring

DID YOU FEEL IT? WE CERTAINLY DID. WE FELT THE world suddenly get a little smaller. It happened just recently, at the precise moment Honda announced the availability of its latest ultra-tourer,

the GL1500 Gold Wing. Because as soon as that roaddevouring luxo-bike became a you-can-buy-one reality, all distances, between all places, instantly grew noticeably shorter.

Now. for those of you who don’t already know, this newest Gold Wing is still powered by a horizontally opposed engine, but one with more cylinders-two more, to be exact, for a grand total of six. A lot of people expected as much, considering that rumors of a six-cylinder Wing have been ricocheting around the industry like bullets in Beirut over the last couple of years. Besides. Honda’s designers have been intrigued by the idea of a six-cylinder touring bike all along, evidenced by the fact that the first running prototype of the original Gold Wing, the 1975 GL 1000, was a flat-Six.

They chose not to make the GL a Six back then, sensing that the riding public wasn't ready for a bike with a halfdozen cylinders. Hell, people were just getting used to the idea o(four cylinders. But that was then and this is now. Honda believes that the time is right for a six-cylinder touring rig, that today’s technology can allow sudi a machine to be smoother, quieter, more comfortable and more refined than anything else prowling the interstates. Honda also figures that if it sweetens the pot even more by throwing in a reverse gear-so you can back up out of those deadend places you regret having ridden down into-you won’t be able to resist.

Obviously, the GLI500 is Honda's reaction to evertoughening competition in the turn-key touring arena, competition that has threatened the four-cylinder Wing's perennial status as king of the open road. But this is no hastily conceived idea; The first sketches were drawn back in 1983; and between 1985 and the present, Honda built 60 complete prototypes of this new Wing, along with 20 additional prototype Six-cylinder engines, before settling on a final production configuration.

By any standards, that’s a whole lot of prototyping. But because Honda’s touring-bike designers maintain direct lines of communication with touring riders, they knew what they were up against; they understood that before any replacement for the beloved four-cylinder Gold Wing could gain widespread acceptance, it would have to be a clear-cut improvement in practically every way. and that it would have to be dead-nuts rieht the moment it hit the

streets.

And the kinds of improvements the riders were looking for were not easy, either. They wanted a touring machine that would be smoother, quieter, more comfortable and more stable even than previous GLs, which were the industry standards for such things. They wanted more lowend lugging power so they wouldn’t be caught short when carrying heavy loads or pulling a trailer. They wanted a reverse. And despite all that, they still wanted the bike to retain the character of a traditional Gold Wing.

A tall order, to be sure. So. to find out how well Honda had met those ambitious goals, we put our GL1500 through a rigorous, 7000-mile test that included several trips and a few days of riding with a card-carrying authority on Gold Wings—Charles Westphal. Executive Director of the Gold Wing Road Riders Association. As its name indicates, the GWRRA is an organization created exclusively for Gold Wing owners, and currently boasts 40,000 devoted members. Westphal rode with us as we explored some of Arizona's most scenic areas, spending considerable time in the saddle of our test bike in the process. And along the way, he gave us his insights into the most dramatically different GL ever made.

As it turnsout, Westphal's feelings about the 1 500aren't much different than ours. He believes, as we do, that the new Wing carries on in the same traditions as the old. but in greater quantities. “Even though it's all-new, and bigger, heavier and more complex than ever." he said, “it’s a continuation of all the positive aspects of the past." Sort of like all you could ask for in a Gold Wing, and more.

Take the GL's 1 520cc engine, for instance. It is the most complicated and automotive-like powerplant ever stuffed into a motorcycle (see “Six For The Road.” pg. 66 ), yet its performance seems perfectly suited to the needs of America’s touring riders. With only a 5500-rpm redline, it’s an unusually low-revver tuned to produce tremendous torque at low engine speeds; but at the same time, it is exceptionally light-flywheeled, so it revs with lightning quickness. The end result of this odd combination is an engine that pulls like a freight train at low' revs; and although it flattens out a bit between about 2000 and 4000 rpm, it zips through its last 1500 rpm with a sense of urgency while sounding like a hot Porsche 911. But curiously enough, it somehow still feels much like the four-cylinder Gold Wing engines that have gone before it.

In first gear, which is quite low, the Six has enough poop to make pulling away from a dead stop a no-sweat affaireven on a steep uphill grade with a full load on the bike and a trailer in tow. But in terms of maximum acceleration, this 1500 Six is only marginally quicker than last year’s 1200 Four, and is slower than Kawasaki's 1 200cc Voyager and Yamaha's 1300cc Venture. Westphal was quick to point out, however, that most Wing riders don’t give a rat’s behind about things like quarter-mile acceleration and top speed, instead preferring the kind of power that can drag them up and over mountain grades without having to tap-dance on the shift lever.

We found that more than a little ironic, since the 1500 does not have exceptional top-gear acceleration, either. It actually makes a lot of mid-range power, but high gear is so tall and the bike is so heavy (875 pounds without gas or rider) that it doesn’t exactly rocket forward when the throttle is dialed open at cruising speeds. It's no match for a Yamaha Venture or a Suzuki Cavalcade in a top-gear roll-on contest, and it needs at least one downshift of its very-wide-ratio gearbox, sometimes two. to make quick passes out on the highway. So, if GL 1 500 riders want their mountain-climbing always to be one-gear affairs, they'll most likely have to use fourth rather than fifth.

On the other hand, the combination of six cylinders, tall gearing and a low-rpm powerband—with the help of rubber cushions at all engine-mounting points—has given the 1500 something that touring riders will revere: the smoothest and quietest engine in the business. Although four-cylinder Wings were velvety-smooth at most speeds, they gave off just enough of a buzz at times to be annoying; they also had an ever-present gear whine that could prove bothersome on long rides. But the Six is so ethere-

ally smooth that, for all practical purposes, you cannot feel it running at any rpm; and a redesign of the driveline has altogether eliminated gear whine. Virtually no mechanical noise whatsoever emanates from beneath the smooth, almost seamless body panels that enclose all of the engine but the cylinder heads. The result is a very soothing engine that lacks the frenetic feel you might expect with a Six.

You might also expect that a bike about 100 pounds heavier and 4 inches longer than its already-large predecessor would handle miserably; but that's not the case with the Six, which handles at least as well as the GL 1200 Four in most normal situations. It does, admittedly, feel more cumbersome at parking-lot speeds, and takes more muscle to flick back-and-forth quickly through an S-turn. And anyone who tries playing roadracer on the 1500 will quieklv find that it has even less cornering clearance than the 1200, easily dragging the crash bars and the front of the fairing.

But touring people don't ride that way. a fact Westphal couldn’t state emphatically enough the first time he saw us making sparks fly from the 1 500’s underside. When cornered in a more realistic fashion, though, the Six is amazingly agile for a bike so large. It banks over fairly easily with just a slight nudge on the high, wide handlebar; and as long as it's moving faster than a walking pace it remains quite stable and composed, whether rounding a turn or droning straight ahead.

Part of that composure comes from larger tires and wheels than those on later-model Gold Wings. The Six has an 18-inch w heel up front and a 16-incher at the rear, as opposed to the 16/15 combination on recent GLs. The tires are K177 Dunlops developed just for this bike, and they gave good wear characteristics and excellent gription during our test.

There also are some suspension differences between the 1500 and its immediate predecessors. The front fork is a sturdy unit with 4 1 mm tubes and no adjustments whatsoever. But because its spring and damping rates seem spoton for a w ide variety of riding styles and road conditions, it always provided an excellent ride and kept the front end planted at all times.

In the rear, the Six retains a traditional dual-shock arrangement. but with two different suspension units—a conventional coil-spring shock on the left, and an air shock on the right. The Wing still has an onboard air-compressor that allows either automatic or manual leveling of the bike, but it now' does so by changing the air volume only in the right-hand shock—a cost-cutting measure on Honda’s part. We found that keeping the pressure between 40 and 50 psi worked well for higher speeds and/or heavier loads, and that 20 to 30 psi w'as best for a Cadillac ride.

In all fairness, much of the credit for the GL 1 500’s fine ride must go to its remarkable seat—which is a story in itself. Touring riders are always in search of a seat that is comfortable for more than a tank of fuel, and Honda took extraordinary measures to give them one. During the latter stages of development, the company hired riders of various sizes and shapes to ride prototypes of the 1500 for weeks on end; the group was followed by a van that carried an experienced seatmaker, along with all of the tools and equipment he needed to modify existing seats or make entirely new ones. And as the entourage wandered around the country, the seatmaker continually made on-the-spot alterations to the seats until the comfort level was optimized.

It's no wonder, then, that the GL1500 has the most comfortable production saddle ever to caress a touring rider's buns. It is broad and deep and intelligently shaped, with built-in lower back support. And the passenger’s area is just as comfortable as the rider's section.

With a couple of minor exceptions, the rest of the ergonomics are quite good, as well. The “magic triangle.” the all-important seat/bar/footpeg relationship, is roomy without being a stretch for riders of average height, and the passenger area includes a comfortable backrest, wellplaced grab rails and even little armrests that have provisions for the rear speakers. The only problems are that: 1 ) the rider's footpegs and the passenger's footboards are too close, often causing the passenger’s feet to bang into the backs of the rider's legs; and 2) the rider's shins tend to hit the backs of the pegs when he or she puts a foot down at a stop. After a day or two of tender shins, you soon learn to put your feet somewhere else when stopped.

You'll probably want to keep both feet down when backing up the 1 500, though, since piloting a half-ton of two-wheeler in reverse is not a natural act. But it’s easy enough to do; with the engine running and the transmission in neutral, you simply lift the special reverse lever on the left-side knee panel, then punch the engine start button. That energizes the starter motor, which propels the bike backwards. The system employs some sophisticated electronics that regulate the voltage to the starter so the bike always backs up at precisely one mph, no matter if it’s going uphill, downhill or on the level. Westphal predicted that riders who pull a trailer will find this feature a lifesaver, but that just about everyone will absolutely love it. They'll also love the protection offered by the Six’s full fairing. Its unusually wide windshield can be adjusted for height over a 2'/2-inch range simply by lifting two locking levers and repositioning the shield. We found that the highest position provides terrific wind protection for both rider and passenger, and that the lowest is best for those hot days when you want as much wind on you as possible. The flow-through ventilation system also delivers reasonable amounts of cooling air; and for cooler days, a vent on each side of the lower fairing ducts hot air from the engine to the rider’s legs. But because the all-enclosing bodywork shields even the exhaust system, the GL 1 500 never seems to get too hot, even on blistering days.

Other aspects of the new Wing’s touring hardware seem just as well thought-out. The non-detachable luggage, for instance, has much more carrying capacity than you’ll find on any other touring bike, and the bags and tail trunk use a unique latching system that involves no external hardware. One lock in the trunk secures all three units, with hidden levers on the underside of the trunk that open the individual compartments. Saddlebag loading is through the sides of the bags, which hinge near the bottom so they open outward for easy access. And the tail trunk is deeper and wider, and thus more spacious than ever. Some riders did complain, however, that if the soft bag-liners were stuffed full, they were difficult to cram into the saddlebags, and that once in place, they made closing the lids rather difficult.

No complaints about the stereo system, though, which is all-new and improved. The controls are now located between the rider’s knees, near the base of the dummy fuel tank, and include five dials and nine pushbuttons. Everything is oversized for easy, no-look operation, even by a rider wearing heavy winter gloves. And sound-wise, as two-speaker systems go (the rear speakers are a Hondaline option), this one is about as good as you can get. especially since it includes a built-in. 24-watt-per-channel amplifier as standard equipment.

All of this adds up to a machine that most committed touring riders will indeed find hard to resist. There’s no doubt that some will be put off by its utter complexity, while others will be intimidated by its sheer bulk. But it seems very likely that since most touring riders subscribe to the more-is-better school of thinking, the GL 1 500 will immediately become the ultimate tourer, if for no other reason than having more of everything—length, width, height, weight, smoothness, power, displacement, cylinders, complexity, storage capacity and, most important of all to some, status.

But wretched excess aside, the GL 1500 also happens to be one mighty fine touring machine, arguably the very best, in fact. As an all-around motorcycle, it might not be quite as good as previous Gold Wings, but it’s a distinct cut above when it comes to swallowing mile after mile of open road. In smoothness and comfort and sophistication it has no peer. Yes, you can buy touring rigs that are faster or better-handling or far less-complicated, but as Westphal keeps insisting, most touring riders simply don’t care about such things. What they care about is luxury; and that’s a commodity the GL 1 500 Gold Wing Six certainly delivers.

In spades.

HONDA

GL1500 GOLD WING

$9998