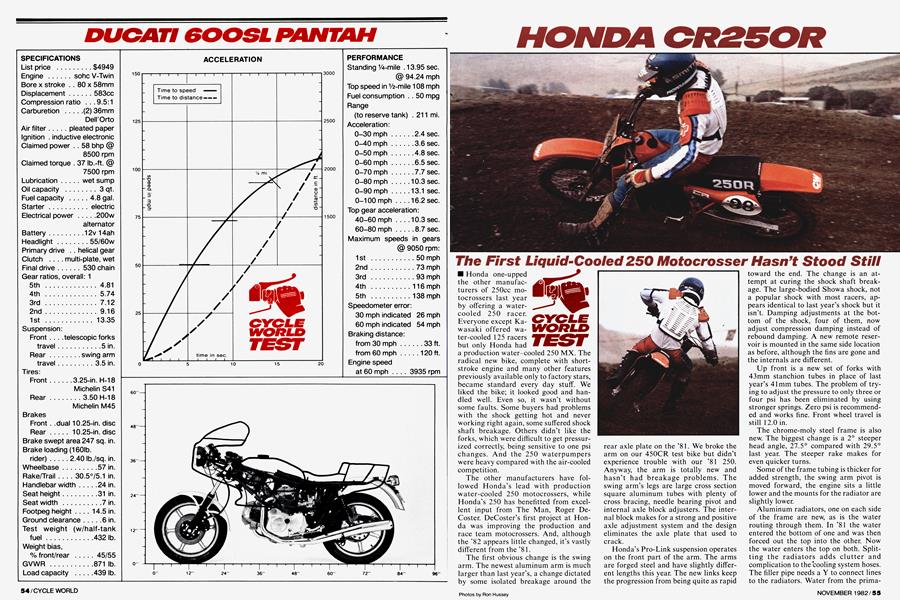

HONDA CR250R

CYCLE WORLD TEST

The First Liquid-Cooled 250 Motocrosser Hasn’t Stood Still

Honda one-upped the other manufacturers of 250cc motocrossers last year by offering a water cooled 250 racer. Everyone except Kawasaki offered water-cooled 125 racers but only Honda had a production water-cooled 250 MX. The radical new bike, complete with short-stroke engine and many other features previously available only to factory stars, became standard every day stuff. We liked the bike; it looked good and handled well. Even so, it wasn't without some faults. Some buyers had problems with the shock getting hot and never working right again, some suffered shock shaft breakage. Others didn't like the forks, which were difficult to get pressurized correctly, being sensitive to one psi changes. And the 250 waterpumpers were heavy compared with the air-cooled competition.

The other manufacturers have followed Honda’s lead with production water-cooled 250 motocrossers, while Honda’s 250 has benefitted from excellent input from The Man, Roger DeCoster. DeCoster’s first project at Honda was improving the production and race team motocrossers. And, although the ’82 appears little changed, it’s vastly different from the ’81.

The first obvious change is the swing arm. The newest aluminum arm is much larger than last year’s, a change dictated by some isolated breakage around the rear axle plate on the ’81. We broke the arm on our 450CR test bike but didn’t experience trouble with our ’81 250. Anyway, the arm is totally new and hasn’t had breakage problems. The swing arm’s legs are large cross section square aluminum tubes with plenty of cross bracing, needle bearing pivot and internal axle block adjusters. The internal block makes for a strong and positive axle adjustment system and the design eliminates the axle plate that used to crack.

Honda’s Pro-Link suspension operates on the front part of the arm. The arms are forged steel and have slightly different lengths this year. The new links keep the progression from being quite as rapid

toward the end. The change is an attempt at curing the shock shaft breakage. The large-bodied Showa shock, not a popular shock with most racers, appears identical to last year’s shock but it isn’t. Damping adjustments at the bottom of the shock, four of them, now adjust compression damping instead of rebound damping. A new remote reservoir is mounted in the same side location as before, although the fins are gone and the internals are different.

Up front is a new set of forks with 43mm stanchion tubes in place of last year’s 41mm tubes. The problem of trying to adjust the pressure to only three or four psi has been eliminated by using stronger springs. Zero psi is recommended and works fine. Front wheel travel is still 12.0 in.

The chrome-moly steel frame is also new. The biggest change is a 2° steeper head angle, 27.5° compared with 29.5° last year. The steeper rake makes for even quicker turns.

Some of the frame tubing is thicker for added strength, the swing arm pivot is moved forward, the engine sits a little lower and the mounts for the radiator are slightly lower.

Aluminum radiators, one on each side of the frame are new, as is the water routing through them. In ’81 the water entered the bottom of one and was then forced out the top into the other. Now the water enters the top on both. Splitting the radiators adds clutter and complication to the cooling system hoses. The filler pipe needs a Y to connect lines to the radiators. Water from the primary-driven pump leaves in a single hose, then divides into two hoses, one for each radiator. Water leaving the radiators has to be merged again, before it gets to the pump. One radiator instead of two would eliminate the complication.

Last year's mostly new engine has a few changes; different porting, pipe, slightly higher compression, and a 3 lb. reduction in weight. The clutch spins on bearings instead of bushings, transmis sion gears have the same ratios but have better engagement dog shapes. Add a different advance curve to the CDI igni tion and you have the new pieces. The carb is still a 36mm Keihin, the six-petal

reeds are steel and the primary kick start lever is still on the left. Last year's neat aluminum shift lever with steel tip that folds and uses a rubber tendon instead of a conventional return spring, is still stan dard and still works great.

Both wheel assemblies are new: The front hub has a straighter, higher spoke flange on one side and the spokes are more of a straight-pull design to elimi nate the tight bend next to the hub, the place normal spokes break. The rear hub is similar and also uses straight-pull spokes. Brakes are the same size but the metal in the shoes is lighter. The front is a double-leading shoe, the rear a single leading shoe. The front brake cable has a heavy outer sheath so it doesn't flop into the spokes, the rear is also cable operated this year but it's an exposed cable, much

like that used on RMs. The rear brake pedal is still a neat aluminum part with a steel claw boot surface. Stamped steel footpegs are replaced by cast steel pegs with aggressive tops and good return springs.

Dogleg hand levers, straight-pull throttle and wonderfully soft grips are carried over from last year and are top quality parts. The stupid-looking front number plate has been shelved and a more conventional one with a louvered bottom is used. And yes, the louvers mean it's hell trying to get large numbers to stick. What's wrong with a normal number plate? (Being completely fair, the louvered plate does help air flow to the radiators.)

A new foam air cleaner is used for `82. Some people had trouble last year with the seams coming apart if it was cleaned in gasoline, not a recommended practice but people do it anyway. The new filter uses a glue that isn’t affected by gasoline. Additionally, the air boot is thicker and stronger so the air rushing through doesn’t collapse it.

Many data panel figures are different. The most significant one is weight. With a half tank of premix the ’82 weighed 236 lb., 9 lb. less than last year’s test bike. Quite an accomplishment when the stronger frame and larger forks should have made it heavier. A 3 lb. weight reduction came from the engine, stronger but lighter hubs and brake shoes, ditto the swing arm, all add up. Moving the pivot forward, pulling the fork rake in and using a slightly longer swing arm changed many measurements. Wheel-

base is about 0.5 in. less, swing arm pivot to drive spocket distance dropped from 3.0 in. to a mere 2.8 in., ground clearance is 0.2 in. less, the foot pegs are 0.3 in. higher, the shift lever is 0.3 in. closer to the peg and the new model has substantially more weight on the front wheel46.9 percent for ’81, 48.7 percent for 1982.

As you probably suspect, the many changes to the chassis and engine make the newest Honda 250CR a lot different than last year’s bike. The old and the new feel the same when sitting still— same seat height, same general bar, peg, seat relationship—perfect for the rider who is on the tall side. Like the old, the new is extremely easy to start; one or two prods on the left-side kick start lever and the engine is running. No kickback, no

backfiring, no hassle. As the watercooled engine warms, (allow at least two or three minutes) the rider is aware of the engine’s excellent response and lack of vibration. Hand and foot controls are properly placed and the rider doesn’t have to adapt to any weird lengths or unnatural placements.

Low gear is easily engaged, clutch pull is light and most first-time riders kill the engine before getting underway. Low gear has a tall ratio so MX racers can come off the starting line and not shift until some speed and stability is gained. Add a clutch with a sudden engagement and killing the engine is common until the rider adapts. The sudden clutch action is also favored by most motocross racers; hitting the clutch in the middle of a turn so the bike will explode from the turn is normal technique. And the sudden engagement means the bike will jump from the corner that much better. Shifts are smooth, easy and positive. Once under way all the transmission ratios seem right for racing. Tight turns mean the rider will have to try and slip the clutch until he becomes proficient enough to blast through faster. Of course these racer ratios, tall low and ultra-close spacing between the rest, make the CR250R unsuitable for trail riding or playing for all but pros. But then most major companies make enduro and play bikes for that purpose. As motocross racers get better and more like those you see the factory stars on, the more single purpose they become.

Power output is much different from last year’s 250 CR. Last year’s bike liked to be wound up and most of the power was produced at high revs. The ’82 is a mid-range engine. Revving it high only slows forward motion. Short shifting to keep the engine in the mid-range gives the fastest drag times. The torque pipe and reworked ignition are designed to produce mid-range power and both contribute to a flatness at high revs. Both also contribute to less shifting once the rider learns to hit the clutch in the turns instead of down shifting. Tight turns will, naturally, still require down shifting, but a suprising number can be zipped through with a quick touch of the clutch. Power at the extreme bottom isn’t as strong as it is on some of the other racers—a KX250 for example has more low-end power. So the flat top end power and lack of really low rpm power take some adapting. The new power band is designed to make the bike more competitive and easier to ride but we think last year’s bike was actually easier. It required revs and it was easy to keep wound out. The new bike requires a watch at both ends of the power band. And we think last year’s bike was a little faster in a drag race.

Pulling the rake in 2° and shortening the wheelbase has made the ’82 very quick in tight turns. The farther forward the rider is, the quicker the turn. There is no tendency to skate the front wheel, even on slippery ground. Sliding smooth turns is much like last year’s bike—excellent. Full-lock slides are great fun. The strong frame and swing arm eliminate flex and the bike feels rock solid. We were worried about the steep rake causing head shake when entering whooped turns with the brakes on hard. Our test 480 Honda was scary under such conditions. The 250 doesn’t do it. It comes into bumpy turns under braking with little head shake or other nasty manners. The rear brake is touchy,

though. If applied too hard, and it’s easy to do, the rear wheel will chatter and the bike won’t slow as much as you wanted. The brake is strong but it doesn’t have as much feel as it could. The front is the same strong stopper. It’ll stand the bike on the front wheel real easy. It is a little sudden and lacks ideal progression but most riders adapt quickly.

Suspension changes may or may not be improvements, depending on your point of view. Changing the damping adjustments from rebound to compression sounds good. But on the race track we prefer rebound damping adjustment choice if only one or the other can be adjusted. Having both adjustable like the YZs is ideal. At least the rebound damping is right for most riders as it comes. The adjustable compression damping is another story. The lightest fork setting was more compression damping than many of our testers liked. Riding the CR with the adjuster set on the most compression, number 3, was out of the question. The forks are simply too stiff with maximum damping. The bike is rideable when the forks are set on No. 1 but it can be scary if the track is strewn with rocks. The CR responds to clipping a rock by instantly turning the bars. Too much compression damping is the problem. Fixing the damping shouldn’t be a major job though. If we owned a CR250 we’d take the forks apart and drill the adjuster holes larger. By checking the damping orifices with numbered drills, drilling the No. 2 hole the size of the No. 1, and No. 3 hole the size of No. 2, and using the same progression, enlarging the No. 1 hole, the adjustments would all be useable. And the change would make the new No. 2 adjustment about right for most tracks without rocks. The new No. 1 would work good on rocky tracks. And

someone might even be able to race with the adjustment on No. 3!

The rear suspension is another problem. How long is Honda going to handicap their motocrossers by using Showa shocks? Yes, we know, the Honda factory stars have Showa suspensions, but they have nothing in common with the production parts. We started our testing with the compression adjustment set on number 1. By the end of the first day the adjustment was on number 3. By noon of the second day the adjuster was on Number 4. By the end of the second day the shock was bottoming through the gulleys and no more adjustment was left. The spring preload was correct, allowing about an inch and a half slack. More spring preload only added discomfort to the ride. The shock worked fairly well until our motocross pros got their chance, then they quickly overheated the shock and its action started heading south. Once they got it real hot, about 35 or 40 min. of hard riding on a rough track, the shock never returned to normal again. The heat had wasted the oil. Changing the oil might help but a pro will have to change it every ride. We wouldn’t bother. Pitch the shock and install a Fox Twin-Clicker if you are going to race a CR250R.

With these changes the Honda is a dynamite bike. Too bad it needs the changes. The bike is beautiful to look at, has a strong chassis, many well-made and properly designed pieces, strong wheel assemblies, and with the suspension changes it’s competitive. Many other ’82 motocrossers are competitive with less modifications. But, ’83 is another year and Roger will have had more time to get the proper changes into production. Eighty-three could be the CR’s year. E3

HONDA

CR250R

$2048

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

November 1982 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1982 -

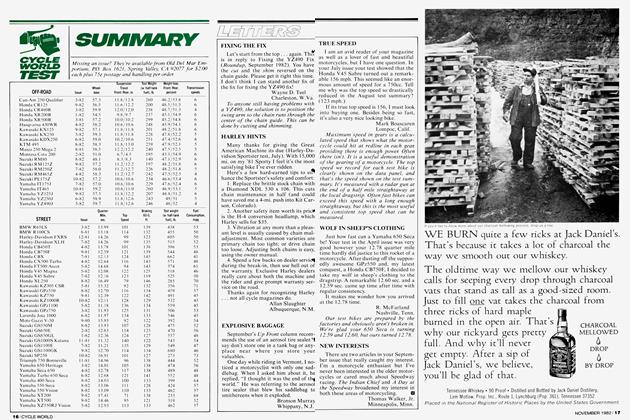

Cycle World Test

Cycle World TestSummary

November 1982 -

Cycle World Roundup

Cycle World RoundupAutomatically Faster

November 1982 -

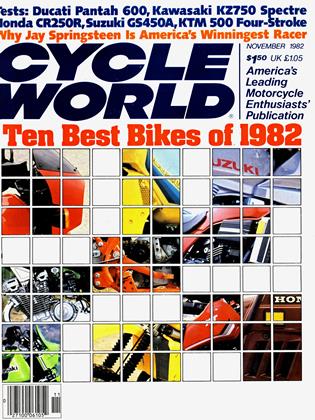

Ten Best Bikes of 1982

Ten Best Bikes of 1982Even When They're All Good, Some Are Better.

November 1982 -

Competition

CompetitionWillie & Jay the Indy Mile

November 1982 By Allan Girdler