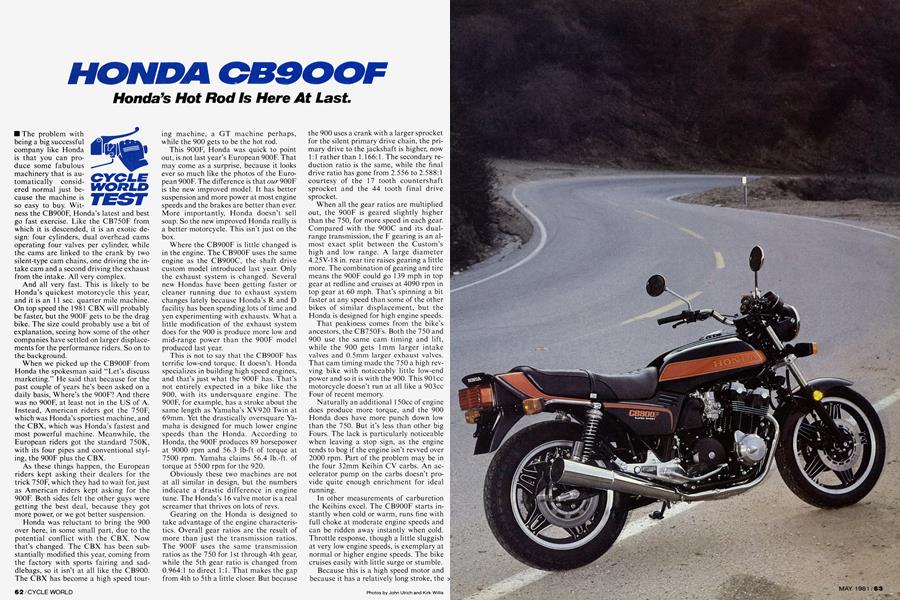

HONDA CB900F

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Honda’s Hot Rod Is Here At Last.

The problem with being a big successful company like Honda is that you can produce some fabulous machinery that is automatically considered normal just because the machine is so easy to buy. Witness the CB900F, Honda’s latest and best go fast exercise. Like the CB750F from which it is descended, it is an exotic design: four cylinders, dual overhead cams operating four valves per cylinder, while the cams are linked to the crank by two silent-type cam chains, one driving the intake cam and a second driving the exhaust from the intake. All very complex.

And all very fast. This is likely to be Honda’s quickest motorcycle this year, and it is an 11 sec. quarter mile machine. On topspeed the 1981 CBX will probably be faster, but the 900F gets to be the drag bike. The size could probably use a bit of explanation, seeing how some of the other companies have settled on larger displacements for the performance riders. So on to the background.

When we picked up the CB900F from Honda the spokesman said “Let’s discuss marketing.” He said that because for the past couple of years he’s been asked on a daily basis, Where’s the 900F? And there was no 900F, at least not in the US of A. Instead, American riders got the 750F, which was Honda’s sportiest machine, and the CBX, which was Honda’s fastest and most powerful machine. Meanwhile, the European riders got the standard 750K, with its four pipes and conventional styling, the 900F plus the CBX.

As these things happen, the European riders kept asking their dealers for the trick 750F, which they had to wait for, just as American riders kept asking for the 900F. Both sides felt the other guys were getting the best deal, because they got more power, or we got better suspension.

Honda was reluctant to bring the 900 over here, in some small part, due to the potential conflict with the CBX. Now that’s changed. The CBX has been substantiali}' modified this year, coming from the factory with sports fairing and saddlebags, so it isn’t at all like the CB900. The CBX has become a high speed touring machine, a GT machine perhaps, while the 900 gets to be the hot rod.

This 900F, Honda was quick to point out, is not last year’s European 900F. That may come as a surprise, because it looks ever so much like the photos of the European 900F. The difference is that our 900F is the new improved model. It has better suspension and more power at most engine speeds and the brakes are better than ever. More importantly, Honda doesn’t sell soap. So the new improved Honda really is a better motorcycle. This isn’t just on the box.

Where the CB900F is little changed is in the engine. The CB900F uses the same engine as the CB900C, the shaft drive custom model introduced last year. Only the exhaust system is changed. Several new Hondas have been getting faster or cleaner running due to exhaust system changes lately because Honda’s R and D facility has been spending lots of time and yen experimenting with exhausts. What a little modification of the exhaust system does for the 900 is produce more low and mid-range power than the 900F model produced last year.

This is not to say that the CB900F has terrific low-end torque. It doesn’t. Honda specializes in building high speed engines, and that’s just what the 900F has. That’s not entirely expected in a bike like the 900, with its undersquare engine. The 900F, for example, has a stroke about the same length as Yamaha’s XV920 Twin at 69mm. Yet the drastically oversquare Yamaha is designed for much lower engine speeds than the Honda. According to Honda, the 900F produces 89 horsepower at 9000 rpm and 56.3 lb-ft of torque at 7500 rpm. Yamaha claims 56.4 lb.-ft. of torque at 5500 rpm for the 920.

Obviously these two machines are not at all similar in design, but the numbers indicate a drastic difference in engine tune. The Honda’s 16 valve motor is a real screamer that thrives on lots of revs.

Gearing on the Honda is designed to take advantage of the engine characteristics. Overall gear ratios are the result of more than just the transmission ratios. The 900F uses the same transmission ratios as the 750 for 1st through 4th gear, while the 5th gear ratio is changed from 0.964:1 to direct 1:1. That makes the gap from 4th to 5th a little closer. But because the 900 uses a crank with a larger sprocket for the silent primary drive chain, the primary drive to the jackshaft is higher, now 1:1 rather than 1.166:1. The secondary reduction ratio is the same, while the final drive ratio has gone from 2.556 to 2.588:1 courtesy of the 17 tooth countershaft sprocket and the 44 tooth final drive sprocket.

When all the gear ratios are multiplied out, the 900F is geared slightly higher than the 750, for more speed in each gear. Compared with the 900C and its dualrange transmission, the F gearing is an almost exact split between the Custom’s high and low range. A large diameter 4.25V-18 in. rear tire raises gearing a little more. The combination of gearing and tire means the 900F could go 139 mph in top gear at redline and cruises at 4090 rpm in top gear at 60 mph. That’s spinning a bit faster at any speed than some of the other bikes of similar displacement, but the Honda is designed for high engine speeds.

That peakiness comes from the bike’s ancestors, the CB750Fs. Both the 750 and 900 use the same cam timing and lift, while the 900 gets 1mm larger intake valves and 0.5mm larger exhaust valves. That cam timing made the 750 a high revving bike with noticeably little low-end power and so it is with the 900. This 901cc motorcycle doesn’t run at all like a 903cc Four of recent memory.

Naturally an additional 150cc of engine does produce more torque, and the 900 Honda does have more punch down low than the 750. But it’s less than other big Fours. The lack is particularly noticeable when leaving a stop sign, as the engine tends to bog if the engine isn’t revved over 2000 rpm. Part of the problem may be in the four 32mm Keihin CV carbs. An accelerator pump on the carbs doesn’t provide quite enough enrichment for ideal running.

In other measurements of carburetion the Keihins excel. The CB900F starts instantly when cold or warm, runs fine with full choke at moderate engine speeds and can be ridden away instantly when cold. Throttle response, though a little sluggish at very low engine speeds, is exemplary at normal or higher engine speeds. The bike cruises easily with little surge or stumble.

Because this is a high speed motor and because it has a relatively long stroke, the engine itself produces quite a bit of vibration. That’s true with the 750 Hondas and with the 900 Custom, though the 900C deals with the vibration with a rubber mounted engine. When the 900C was introduced Honda said rubber mounted engines worked better with shaft drive bikes and that’s why the 750s didn’t have rubber mounted engines. Now here’s the 900F with a rubber mounted engine and chain drive.

This is not the same rubber engine mounting system used on the 900 Custom. It’s not anything like that of the 900C. A chain drive motorcycle must have precise alignment of the engine and rear hub. And to maintain that alignment, not all the engine mounts of the Honda are rubber mounted. One of the mounts is “solid.”

Honda’s solution to the isolation and alignment problem is novel. Rather than use a solid link at the back of the motor as Kawasaki has done with the new KZ1000 and KZI 100 models, all the back mounts on the Honda are rubber mounted. Only the front engine mount is not rubber mounted, and it’s not truly a solid mount either.

Instead, the front engine mounts are links connecting the front of the engine to cast iron junctions in the frame. The links can swivel up and down allowing the engine to move vertically, only controlled by the rubber mounts elsewhere. The only positive location provided by the links is to fore and aft movement. There is even slight lateral movement allowed by the links. Because these links are at the very front of the engine, they have good leverage on the engine for maintaining engine alignment with the final sprocket.

The links connect to the frame at cast iron junctions. The lefthand junction is welded to the frame tubes that slip into the junction. The righthand junction bolts together to clamp the frame tubes into the junction. Because the tubes are a clamped-in slip fit, the lower righthand cradle tube can be removed, as it can be on the 750s, so the engine can be pulled from the frame.

A rubber mounted engine does not necessarily guarantee a smooth running motorcycle. At least one other new motorcycle has a rubber mounted engine this year and it vibrates excessively. The Honda CB900, happily, is not like that. The rubber mounting is not just a more complex system, it is a better working system. The most vibration that comes through may be at idle, where the mirrors can blur and the clutch lever rattles a little. As soon as the bike is moving the vibration fades away. There is a slight tingle through the gas tank and the bars at around 50 mph, but the faster the bike goes, the smoother everything gets.

Vibration is not a new problem and isolating the engine from the frame is not a new solution. Norton did it with the Isolastic frame, Suzuki did it with the GT750 > Triple. More recently Yamaha has done it with the 1 100 and 650 Fours. Ten years ago road testers praised four cylindermotorcycles for the incredible smoothness, so here we are commenting about all the nasty vibration being isolated with rubber mounts.

Four cylinder engines do have smaller impulses than Singles and Twins, and they are in better balance, but there are torsional vibrations and cyclical vibrations and the vibrations of a multi are typically high frequency vibrations that aren’t especially noticeable at first, but become irritating with use. To understand the difference, a ride on Honda’s 750 and 900F models would be in order. The 750 seems particularly harsh and buzzy at cruising speeds, compared with the 900, because of the 900’s rubber engine mounting. And now that so many of the larger bikes are coming with some sort of rubber engine mounting, the difference is more noticeable. Honda’s system on the 900F is now the high water mark for vibration isolation on a chain drive bike.

The low water mark of this motorcycle is shifting. The transmission on the 900 is the same dësign as that of the 750. The 900C used a lower low gear than the 750, and that masked some of the peakiness of the engine. The 900F gets the 750 gear ratios 1st through 4th, not the 900 Custom ratios. It also gets the 750’s disinclination to fully shift into the next gear when run hard.

Since the first dohc 750 Honda was introduced, the various test bikes we've ridden have had a slight problem shifting. Normally, they work fine, requiring moderate pressure to change gears and only occasionally refusing to shift fully into the next gear. But all the bikes in this series, the various 750Fs, the 750C and 750K can slip back out of a gear when accelerating hard. That problem is more pronounced on the more powerful 900F.

At the dragstrip the 900F was at its worst. Only a third of the runs were made without the bike slipping back out of third gear after the 2nd-3rd shift. The rider felt the quarter mile times of the bike could have been cut maybe another two tenths of a second if the bike could have been shifted reliably. Even on the street when riders accelerated hard, the bike would occasionally miss shifts and it was worse on the road race track. And that’s frustrating.

Another irritation on past Hondas that’s been thoroughly improved is braking. All of the past dohc Honda Fours we’ve tested had brakes that were powerful and controllable enough, except that after 1000 or 2000 mi., the brake discs would warp and there would be a pulsing feel through the brake lever. Honda has had a couple of quality control fixes for the problem, but our 1980 Honda 750F still had the problem.

This year Honda has made substantial changes to the brakes on several of its models, using new double piston calipers and different discs. The two caliper pistons ride in tandem, changing the puck shape from a large square to a rectangle. Swept area is slightly less with the new calipers, but the area is farther out from the center of the wheel for more leverage on the disc. That enables the disc to use a narrower band for contact and more room for lightening holes in the center section. The twin piston caliper is also more rigid than the single piston caliper. The single large piston caliper had to wrap farther around the disc in order to house the big piston. The twin piston caliper is smaller, not wrapping as far around the disc, and providing less leverage to spread the caliper apart. As a result the brakes are much more solid, with a less spongy feel at the lever.

Better yet, the stopping distances achieved with the 900F were excellent; 129 ft. from 60 mph and 31 ft. from 30 mph. All three discs are easy to control, powerful enough for an experienced rider to bring the tire right to the verge of locking. The standard for brakes has just gone up a notch.

Suspension pieces on the 900F have been upgraded from the previous Honda F. The most obvious novelty is shock design. When the off-road riders saw the 900F they immediately asked where the Thermo-flow shocks came from. The general style does look like the remote reservoir shocks used by Yamaha ages ago on dirt bikes. But the Honda’s shocks also retain the same adjustments that have been on the 750F shocks the past couple of years. Compression damping is adjusted by a small lever at the bottom of the shock. There are two compression damping settings and three rebound damping settings. Most of the suspension measurements are the same as those of the 750F, that is 4.3 in. of travel and the same spring rates for the new 900F. However the rebound damping adjustments now offer more variation. The stiffest setting is the same, but the lightest setting is 20 percent lighter, the mid-point 10 percent softer.

This year Honda has a new label for its shocks: Variable Hydraulic Damping. They still have relief valves so rebound damping can be reduced when the shocks are pumped fast, as on very bumpy roads. The change of names from Full Variable Quality implies an improvement in quality control. Either that or Honda heard its shocks were nicknamed Fades Very Quickly for the FVQ. In any case, the aluminum reservoirs attached to the 900F’s shocks should increase the oil capacity of the shocks and that should reduce shock fade.

Front suspension is also an improved version of what Honda has had in the past. Fork stanchion tubes are larger on the 900F than they were on last year's 750F or even this year’s 750F. This year the 750 gets 37mm stanchion tubes and the 900F gets 39mm tubes, the same size as those used on the GL 1 100 and on Honda Superbike race machines. In addition, the forks have air caps and softer springs than previous 750s, so that a combination of air and steel springs supports the 900F. Like the 900C, the F has a cross-over tube so only one air cap is needed and air pressure is balanced between the fork tubes.

The benefit of larger stanchion tubes is greater steering precision. This is especially important as fork travel is increased as there’s less engagement. So the 900F gets big fat fork tubes, and it gets a gorgeous forged aluminum lower triple clamp. And a side benefit of the big fork tubes is increased fork oil capacity. The 900F has a capacity of 345cc, compared with 245 for the 750F. Just as the shocks have greater oil capacity to keep temperatures down, the greater fork oil volume keeps fork oil temperature down and helps keep damping constant.

All this suspension refinement is wonderful stuff. The 900F rider can match features with anybody. These features, combined with the powerful 900cc engine, make the CB900F Honda’s most sporting motorcycle. To determine just how sporting it is, we headed for our friendly, neighborhood racetrack. Willow' Springs.

There, the 900F surprised us. The 750F, from which the 900 is developed, is an excellent handling motorcycle, sure and stable and easy to control. The 900 is very good under most conditions, but on bumpy sweeping turns, like Turn Eight at Willow, or the freeway onramp on the way to Willow, the 900F develops an uncomfortable oscillation of the handlebars. Go into a fast, bumpy corner too hard and back off and the motion accelerates, flopping the handlebars back and forth severely. That is not good.

Certainly the 900F can be ridden fast on a racetrack or a winding road. It has good cornering clearance, excellent steering precision for its size, it changes directions well and it has lots of horsepower as long as it’s shifted very carefully. But it must be ridden very carefully. A rider must enter bumpy corners slower than normal so he doesn't have to shut down part way through and be forced to deal with the wiggle in the front end.

At lower speeds, or on smooth corners, the 900F is fine. The big forks do provide a more positive link between the handlebars and the front tire. When the limits of cornering clearance are reached the folding pegs warn the rider and then the center and sidestand scrape. And all the time the brakes are tremendous, slowing the bike faster and more easily than the rider expects.

What limits the Honda’s stability in cornering is not clear. It has a beefy swing arm, pivoting on needle bearings. The shocks seem to have adequate damping, though increasing the damping in the shocks didn’t minimize the handling problems. It is otherwise a solid feeling bike.

There is one obvious handicap to the Honda’s handling. Its weight. With a half tank of gas the Honda weighs 568 lb. That’s a far cry from the 522 lb. claimed dry weight on the Honda brochure. It’s also substantially more than the 535 lb. of the Kawasaki KZ1000J, the 556 lb. of Suzuki’s GS1100E, the 551 lb. of Kawasaki’s GPzl 100, or the 536 lb. of the original Suzuki GS1000.

Much of the handling development of this motorcycle, according to Honda, was done to increase high speed stability. That’s why the 900 uses wider tires than the 750 used. And that’s why the rear wheel has a 2.75 in. rim, rather than the 2.1 5 in. rim used on the 750.

Honda has made the same increase in rear rim width on the 1981 CBX, also in the interests of high speed stability. It might appear strange that Honda could work at improving high speed stability and come out with the 900F that is less stable at speed than the 750F. A look at Honda’s Tochigi test center might provide an answer. It has a beautiful, smooth and fast banked oval, plus a small, smooth road course, but there is no bumpy fast sweeper at the test center.

That doesn’t mean the Honda isn’t enjoyable to ride. Where it shines is on open country roads. Cruising along in top gear with the speedometer needle pegged, the engine feels good, as though it wants to run at 7000 rpm all day long. Above 6000 rpm there’s good power, and when more is needed it's easy to drop down a gear or two and watch the tach touch the redline in each gear.

Suspension compliance is good at speed, and the Honda is a comfortable bike for medium long rides. The 900F seat is padded a little differently than the 750F seat, and it’s more comfortable. The handlebars are excellent for stock bars on a sport bike. They are narrower than the bars on the 750F, bent back enough for comfort, but not so far back to create a problem. If the bars are too high, there’s a low bar kit available, complete with shorter cables.

Controls on Hondas have been excellent for some time now; and the CB900F continues the trend. The grips are solid enough yet easy to hold, the throttle return spring is just a little too stiff. Brake and clutch levers are convenient and operate with moderate pressure. Instrumentation on the 900F is an improved version of the 750 instruments. The dials are translucent so lighting at night is easy on the eyes yet the instruments are readable. The warning lights have very dim bulbs so the neutral, oil pressure and high beam indicators are easy on the eyes at night. Unfortunately they can be too dim to see during the day. The oil pressure warning light lens has been changed so it doesn't reflect sunlight and appear lit the way the lens does on the 750, so a rider not used to the bike doesn't pull in the clutch and kill the engine the first time sun hits the lens from a certain angle.

Unlike some of the other flash bikes, the 900F doesn’t have self cancelling turn signals, which is fine with some riders who think the 900F weighs enough as is. One feature the bike does have that it could do without is a two piece gas cap. Not only is it inconvenient to use and even more so when using a tankbag, but when the hinged clasp is unlocked, the screw-in gas cap still must be put somewhere. The cap could look exactly the same even if Honda attached the cap to the hasp, so a simple unlock and lift allowed the rider to fill the tank.

But the good features outnumber the bad. The 55/60 watt quartz-halogen headlight is bright and lays out a well-defined pattern of light on both low beam and high beam. The choke knob is conveniently located right beside the ignition switch, which, in turn, includes a fork lock. How nice.

Dual horns on the 900F are amazingly loud. Some cars don't have horns as audible. Mirrors use Honda's tubular stalks that damp out vibration so well. The sidestand, just like all the other Hondas, has a small rubber tip that retracts the stand if the rider forgets to, as soon as the tip hits the pavement.

Even little touches like the rubber mounts on the turn signals and the pushbutton trip meter reset and the brake fluid reservoir that's translucent so you can check brake fluid level, all make the 900F an easy bike to live with.

What the Honda CB900F does best is look like a sports bike. The swoopy styling that first appeared on the 750F still looks good with the bold red-orange laser strip on the side of the gas tank. Perhaps the orange is a little halloween-like for some tastes, but the silver-blue combination is fine for the more subtle. Other pieces, like the oil cooler on the frame downtubes, the forged aluminum triple clamp, the wing on the plastic front fender that actually cools the oil temperature a couple of degrees, all make the bike look fast and sporting.

That striking appearance, combined with real improvements should also assure Honda of success. For the Honda rider who wants a step up from his 750F. the 900F is an excellent answer. It’s fast, smooth, comfortable and also a thoroughly useable bike.

It isn't as sporting as a number of other machines now available. As much as that may offend the hardest riders, it makes the bike better for most riders. The suspension that’s a little too soft and compliant for the most precise handling makes the bike more comfortable for long rides. The big gas tank that adds weight with more gas also enables the bike to go farther between fill ups.

Honda’s answer for the sports-utility equation is on the plush side of the problem, and for most riders it might be the right answer.

HONDA CB900F

$3495