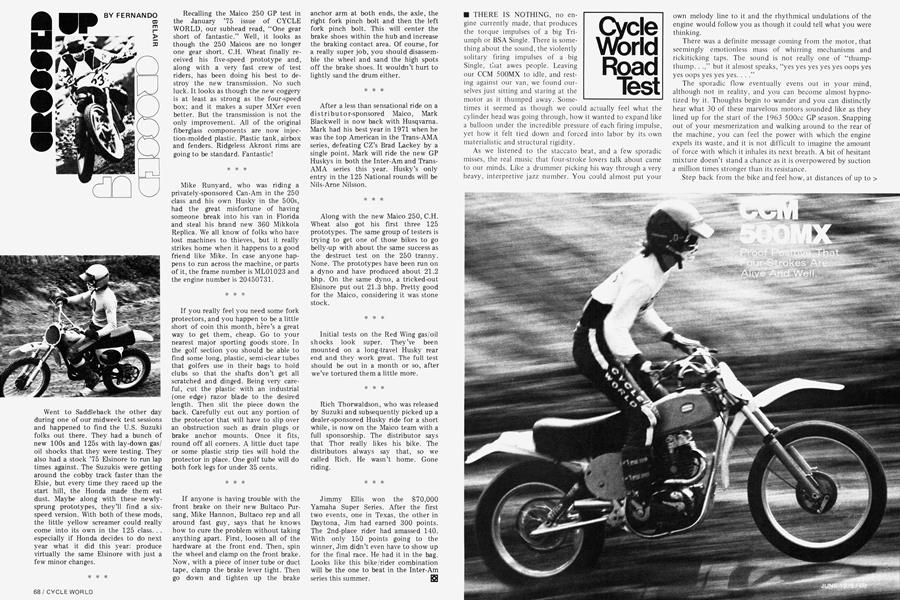

CCM 500MX

Cycle World Road Test

Proof Positive That Four-Strokes Are Alive And Well.

THERE IS NOTHING, no engine currently made, that produces the torque impulses of a big Triumph or BSA Single. There is something about the sound, the violently solitary firing impulses of a big Single, that awes people. Leaving our CCM 500MX to idle, and resting against our van, we found our-selves just sitting and staring at the motor as it thumped away. Some-

times it seemed as though we could actually feel what the cylinder head was going through, how it wanted to expand like a balloon under the incredible pressure of each firing impulse, yet how it felt tied down and forced into labor by its own materialistic and structural rigidity.

As we listened to the staccato beat, and a few sporadic misses, the real music that four-stroke lovers talk about came to our minds. Like a drummer picking his way through a very heavy, interpretive jazz number. You could almost put your own melody line to it and the rhythmical undulations of the engine would follow you as though it could tell what you were thinking.

There was a definite message coming from the motor, that seemingly emotionless mass of whirring mechanisms and rickiticking taps. The sound is not really one of “thumpthump. . but it almost speaks, “yes yes yes yes yes oops yes

yes oops yes yes yes. . . .”

The sporadic flow eventually evens out in your mind, although not in reality, and you can become almost hypnotized by it. Thoughts begin to wander and you can distinctly hear what 30 of these marvelous motors sounded like as they lined up for the start of the 1963 500cc GP season. Snapping out of your mesmerization and walking around to the rear of the machine, you can feel the power with which the engine expels its waste, and it is not difficult to imagine the amount of force with which it inhales its next breath. A bit of hesitant mixture doesn’t stand a chance as it is overpowered by suction a million times stronger than its resistance.

Step back from the bike and feel how, at distances of up to 50 feet, you still get hit in the face with an air blast strong enough to force you to close your eyes.

These sensations, which at one time were taken for granted, are becoming more and more rare as the two-stroke engine begins to shut the gate on the off-road racing market it has corraled.

But the off-road market is still full of successful four-stroke engines, which makes many people believe that there is still a place for the quadra-stroke in racing. Maybe so, but thumpers suffer from a couple of problems that must be overcome if they are to be successful racers. The foremost of these is weight. Eliminating it costs money. Lots of money. The second problem is the location of that weight. Here, there is little that can be done. Four-strokers are much more top-heavy than their ring-ding counterparts. So, going into the battle, the thumper is already down a couple of points.

CCM makes some of the finest BSA-powered motocrossers available. They do their best to whittle away at the weight; unfortunately pounds lost mean dollars added to the price of the product. CCM wants to make up that weight point but they lose it right back in cost.

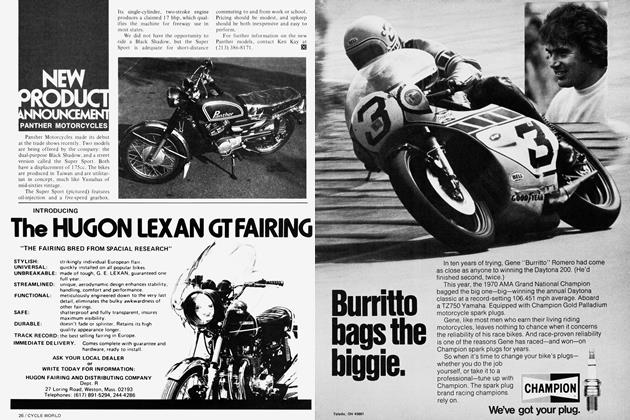

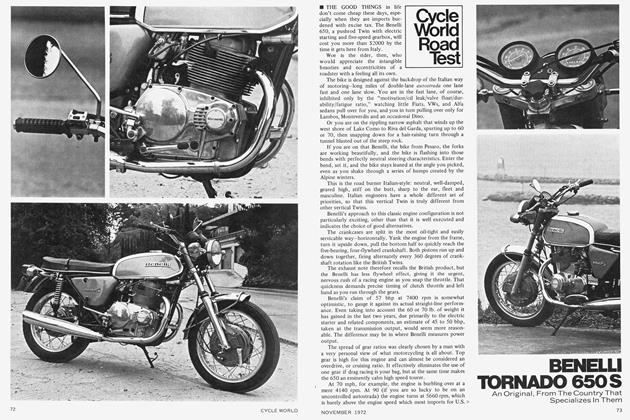

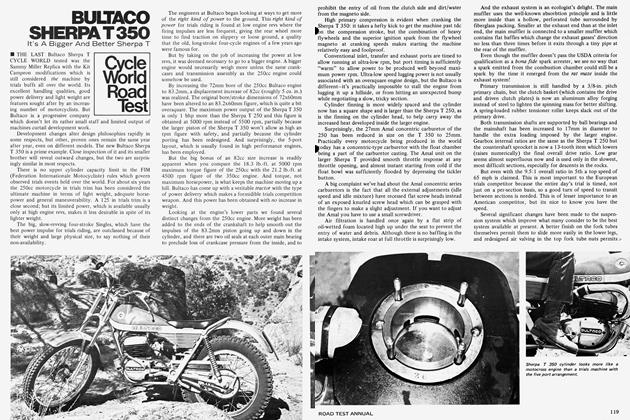

The latest version of the CCM 500MX arrived at our CYCLE WORLD offices from the distributor. As we uncrated it and began assembly, several things caught our eye. Immediately we noticed the slanted shock absorbers, run in an inverted position, with an oil line running into the rear fender loop that serves as a reservoir. We noticed the magnesium side cases, hubs and brake backing plates. The frame is made from 531 Reynolds tubing and the welds are perfect. They have to be because the front downtube and the backbone frame member serve as the oil tank for the dry-sump engine.

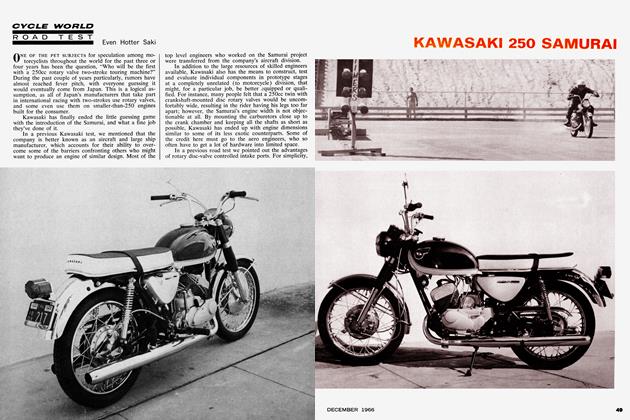

The engine in our test bike was a prototype. The normal bore and stroke measurements of 90x90 were altered to 82x88. Total displacement is 464cc. Of course, with any machine of this type that commands a purchasing price above $2500, you get all of the lightweight internal goodies. Alloy primary pinion and clutch hub, lightened crankshaft and lightweight pushrods are all part of the package. The cylinder head has been ported, and larger valves have been installed. The standard compression ratio has been raised to 10.0:1 and the cam is much more radical than the Stocker’s. All told, the engine was extremely impressive. With more than 36 horsepower on tap, along with notorious thumper tractability, riders never lacked for power. In standard trim, the BSA Victor engine (now incorporated under the Triumph name as the Avenger), puts out a meager 24hp on the Webco dyno. The output increase in the new prototype engine measures a whopping 33 percent!

We noticed right away that no compression release had been fitted to the CCM. On a large Single such as this, the compression release serves to reduce cylinder pressure so that the crank may spin more freely to position it better for starting. But without the compression release, all we could do was push the crank through until the piston was rising through its compression stroke. Then we brought the kickstarter back to the top of its arc and, with a violent body heave and a silent prayer, tried to start it.

When fhe engine was warm, holding the throttle half-way open would produce the easiest starts. When cold, it was necessary to tickle the Amal carburetor until it flooded out the side. Then the throttle had to be opened all the way and tickled again for half a second or so. This allowed a raw charge of fuel into the intake tract. Kicking the engine through a few times with the ignition turned off would set the combustion chamber up for a rich-condition start. Flipping the ignition switch on and kicking through, following the warm-engine procedure, would usually produce instant firing.

The ignition arrangement on the CCM is rare for a production (albeit very limited) motorcycle. It is a constant loss system that runs off a pair of small rechargeable batteries. The power sources may be renewed without having to be removed from their location inside the airbox. A pair of “jumper” wires comes with the bike. One of the wires plugs into a phone-type jack behind the left number plate. This wire connects to the positive pole on either a car or street bike battery. The other wire connects from the negative battery pole to any ground surface (such as a cylinder fin) on the bike. A half-hour charge is good for about three hours riding time. From the batteries, the juice runs through a standard pair of points, to the high-tension coil and then to the spark plug. The on-off switch is located on the left side, below the seat and to the rear of the number plate.

Externally, some modifications have been carried out on the engine in the interest of saving weight. Although the front portion of the cylinder remains untouched, every other fin down each side has been deleted. Since, at a rev maximum of 7000, there are only 3500 combustions taking place each minute, cooling is less critical than on a two-stroke. Thus, the reduction in fin area is not critical. The original side cases have been replaced with mildly-finned magnesium counterparts, which also serve as the mounting points for the footpegs. The side cases are gold anodized and very attractive. They match the coloring of the magnesium brake hubs and set off the shine of the brilliant nickel-plated frame.

Both brakes are half-width units and their performance proved excellent during our test. Of course, with the braking power of a four-stroke engine, the rear binder didn’t have to be as good as it was, but it never hurts to have a little extra in reserve. We did experience a failure of sorts with the front hub. Since magnesium is a soft metal, it can be ground away easily. For unknown reasons, an amount of magnesium was ground away from the outer lip of the hub and collected on an area between the hub and the backing plate that covered approximately one fourth of the circumference of the hub’s sealing lip. This caused the front wheel to lock up and put an end to our testing on that day. We disassembled the hub, scraped away the accumulation of metal on that portion of the hub, and that was the end of our mechanical problems with the CCM.

With the current trend in modified suspension, you would expect a machine costing as much as the CCM to have the latest setup. It does. The rear shock absorbers are made by Koni and they have valves at their bases (in their inverted position this translates as valves at their tops), that are connected by short pieces of hose to the rear fender loop. This increased oil volume aids cooling. The cooler you are able to keep the oil in a hydraulic system, the more constant the viscosity and the resultant damping will be.

At the other end of the bike, there is a pair of custom made forks that, along with more than eight measured inches of travel, also have adjustable damping. The forks need not be disassembled to alter the rebound control rate, as there is a small Allen screw a few inches above the axle that handles that chore. Just dial in the amount of control you want for any particular track and you’re set. It would be a good idea to install a pair of plastic fork protectors, since the lower fork legs are also magnesium and a stiff blow from a flying rock could easily render one of them useless.

For some reason, the British have almost always shied away from using ultra-light rims such as Akronts (D.I.D.s, originating from Japan, have proven too costly) on their off-roaders. Instead, they almost always use high-tensile steel rims that have less resistance to bending pressure than alloy rims, but are much more flexible and will bounce back to form. The high-tensile rims are a bit lighter than regular steel rims, but the difference is negligible.

Total weight of the CCM is competitive when one considers what Maico 450s and Yamaha monoshock 400s weigh, but it is far from that of the superlight machines such as the Bultaco or Husqvarna 360s. Yet machines like the Maico and Yamaha don’t feel like they weigh as much as they do. The CCM does. This can be attributed to the location of the weight. As mentioned earlier, this is an innate problem with vertical four-stroke engines. On the track you can feel the weight of the machine under you as you ride. The weight is beingjostled around, not at your ankles, but between your knees. Body English has much less effect than normal. The bottom half of the bike gets pitched around a bit, but the upper half remains on line. The situations you can get yourself into with this combination can be very thrilling.

The CCM steers very well. It also soaks up bumps easily at either end with its long-travel legs. The four-speed transmission shifts on the right and, with the available power, you’ll never lack for the right amount of oomph. But the bike is a sit-down type of machine. It is common practice to place the footpegs far forward on a four-stroke MXer, because placing the weight any farther back would make the machine a perennial wheelier. It gets enough traction as it is. But we never could get ourselves accustomed to standing and having our knees touch the handlebars. This also forced us into a very bent-over position in order to hold the bars. We really think that the footpegs should be farther back and that it should be up to the rider to place his weight forward if that’s where he wants it.

One final complaint. The position of the rear brake pedal was so far out of the way of normal foot motions that it could actually be dangerous. We don’t think that it would be difficult to cut and reweld the brake pedal so that it falls readily into place, but every time you cut or weld something on such a bike, you then have to replate that item.

The CCM has the makings of a great play bike. Even though its range is limited by the short life of its total-loss ignition system, a rider can carry a spare set of pre-charged batteries in his pocket in order to enjoy a full day’s ride. For such play bike use, a larger fuel tank would be needed and we suggest installing a set of unbreakable plastic fenders. The stock fiberglass ones won’t last through very many spills.

As a motocrosser, yes, the CCM is competitive. With the right rider, it can be successfully raced. But only in sub-Expert classes. We seriously doubt that four-strokes will ever again become consistently competitive in professional motocross.

The CCM is a motocrosser for very few people. The factory doesn’t make all that many of them, but should be able to sell them all. It is a very fine, very exotic motorcycle. Some people would like to own one to race it. More power to them. But there are folks in this world who would, as we would, like to own one just to sit and listen to its sounds, and the stories they tell.

CCM

500MX

$2600

View Full Issue

View Full Issue