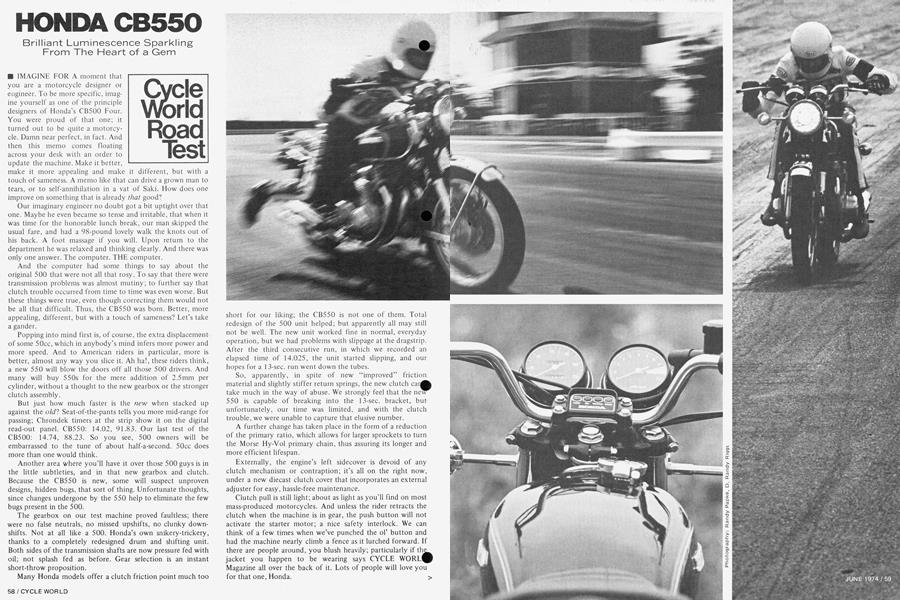

HONDA CB550

Cycle World Road Test

Brilliant Luminescence Sparkling From The Heart of a Gem

IMAGINE FOR A moment that you are a motorcycle designer or engineer. To be more specific, imagine yourself as one of the principle designers of Honda's CB500 Four. You were proud of that one; it turned out to be quite a motorcycle. Damn near perfect, in fact. And then this memo comes floating across your desk with an order to update the machine. Make it better,

make it more appealing and make it different, but with a touch of sameness. A memo like that can drive a grown man to tears, or to self-annihilation in a vat of Saki. How does one improve on something that is already that good?

Our imaginary engineer no doubt got a bit uptight over that one. Maybe he even became so tense and irritable, that when it was time for the honorable lunch break, our man skipped the usual fare, and had a 98-pound lovely walk the knots out of his back. A foot massage if you will. Upon return to the department he was relaxed and thinking clearly. And there was only one answer. The computer. THE computer.

And the computer had some things to say about the original 500 that were not all that rosy. To say that there were transmission problems was almost mutiny; to further say that clutch trouble occurred from time to time was even worse. But these things were true, even though correcting them would not be all that difficult. Thus, the CB550 was born. Better, more appealing, different, but with a touch of sameness? Fet’s take a gander.

Popping into mind first is, of course, the extra displacement of some 50cc, which in anybody’s mind infers more power and more speed. And to American riders in particular, more is better, almost any way you slice it. Ah ha!, these riders think, a new 550 will blow the doors off all those 500 drivers. And many will buy 550s for the mere addition of 2.5mm per cylinder, without a thought to the new gearbox or the stronger clutch assembly.

But just how much faster is the new when stacked up against the old! Seat-of-the-pants tells you more mid-range for passing; Chrondek timers at the strip show it on the digital read-out panel. CB550: 14.02, 91.83. Our last test of the CB500: 14.74, 88.23. So you see, 500 owners will be embarrassed to the tune of about half-a-second. 50cc does more than one would think.

Another area where you’ll have it over those 500 guys is in the little subtleties, and in that new gearbox and clutch. Because the CB550 is new, some will suspect unproven designs, hidden bugs, that sort of thing. Unfortunate thoughts, since changes undergone by the 550 help to eliminate the few bugs present in the 500.

The gearbox on our test machine proved faultless; there were no false neutrals, no missed upshifts, no clunky downshifts. Not at all like a 500. Honda’s own snikery-trickery, thanks to a completely redesigned drum and shifting unit. Both sides of the transmission shafts are now pressure fed with oil; not splash fed as before. Gear selection is an instant short-throw proposition.

Many Honda models offer a clutch friction point much too short for our liking; the CB550 is not one of them. Total redesign of the 500 unit helped; but apparently all may still not be well. The new unit worked fine in normal, everyday operation, but we had problems with slippage at the dragstrip. After the third consecutive run, in which we recorded an elapsed time of 14.025, the unit started slipping, and our hopes for a 13-sec. run went down the tubes.

So, apparently, in spite of new “improved” friction material and slightly stiffer return springs, the new clutch car^fc take much in the way of abuse. We strongly feel that the new^ 550 is capable of breaking into the 13-sec. bracket, but unfortunately, our time was limited, and with the clutch trouble, we were unable to capture that elusive number.

A further change has taken place in the form of a reduction of the primary ratio, which allows for larger sprockets to turn the Morse Hy-Vol primary chain, thus assuring its longer and more efficient lifespan.

Externally, the engine’s left sidecover is devoid of any clutch mechanism or contraption; it’s all on the right now, under a new diecast clutch cover that incorporates an external adjuster for easy, hassle-free maintenance.

Clutch pull is still light; about as light as you'll find on most mass-produced motorcycles. And unless the rider retracts the clutch when the machine is in gear, the push button will not activate the starter motor; a nice safety interlock. We can think of a few times when we’ve punched the ol’ button and had the machine nearly climb a fence as it lurched forward. If there are people around, you blush heavily; particularly if the jacket you happen to be wearing says CYCFE WORFl^P Magazine all over the back of it. Fots of people will love you for that one, Honda.

A quick once-over gives an impression of careful assembly and high-quality components; closer inspection reveals an outstanding overall finish. Pop the sidecovers, unlock and lift the hinged seat, prod even deeper; it gets better.

Careful, precise routing of wiring eliminates confusion when troubleshooting. Rubber seals, dust covers and incidentals make the electrics as reliable as they appear. There’re even spare fuses for the centrally-located fuse panel.

Lighting and switches work in a very decent sort of manner. We still object to the ignition switch location under the tank, and even more so to the position of the high beam dimmer button, but they’re small prices to pay when one considers the entire electrical package. We just keep hoping for perfection.

Forget to shut off the turn indicators? This one has an audible beeper to remind you that they’re on. There’s even a lane-change feature built into the switch—we’d like to see that become an industry-wide practice.

CB750 riders will recognize the 550’s instruments, because both bikes utilize the same units. Readability (both day and night) must be praised highly; and naturally, a resettable trip odometer is included. The familiar warning light panel finds a spot on the new 550, as do the rock-hard handlebar grips that we’ve complained about for so long.

There is no doubt that the 550 is more motorcycle than the 500 was, but more of everything isn’t necessarily on the plus side. The base price has risen, of course, just like the cost of everything these days. The 550, at $1600 suggested retail, is about $100 more than the original 750 Four, and $250 more than the original 500.

The 550 is also slightly heavier (10 lb.), a bit louder than the 500 (although still one of the quietest machines going), and has a noticeably higher vibration level in the mid-range (although it is still one of the smoothest bikes on the road). And certainly fuel consumption is one thing that can’t be forgotten. Our last 500 test machine averaged just over 50 mpg; the 550 sips slightly more. Many more mpg than you’ll get with any automobile, just the same.

In terms of routine maintenance, the CB offers no problems. However, taking into consideration four-cylinder complexity, the average owner would be well-advised to let his dealer handle the important tune-ups and adjustments. These occur at 3000-mile intervals, with oil changes recommended at 1500. In day-to-day service, the 550 is an extremely economical vehicle; almost a personal means of getting back at the oil companies. With the gasoline situation what it is at present, we would prefer a fuel tank with a larger capacity than the 550’s 2.7 gal., which only allows for a cruising range of about 100 to 120 miles before reserve is needed.

As a medium-displacement motorcycle, the 550 will be appealing to rqany, although cost may deter some. It is powerfûl enough and comfortable enough to make all of the long distance trips an owner would want, yet it isn’t too overbearing in everyday use. Deciding between it and a CB750, for example, could be a tough choice. Lots of two-up traveling or heavily-loaded wayfaring would be easier on a 750 rider. Take the commuting aspect of things, however, and more men cling to the 550’s end of the rope.

What makes the 550 such an ideal short-or-long-haul commuter is not only the engine’s ability to respond to varied situations, but also a very light, nimble handling characteristic. This sort of feeling puts the rider at ease in tight traffic; makes him feel as though he is riding a much smaller motorcycle.

We often find ourselves in a line of cars approaching a stop sign intersection. Each one takes its turn and the line moves slowly, but continuously. This is when it’s always fun to creep along without touching your foot down—quite often a good test of a motorcycle’s clutch actuation, throttle linkage response and cush drive slop.

On the Honda 360G that we tested a short while back (Cw^P Mar. ’74), it was difficult to move along in this kind of traffic without a sloppy jerkiness owing to an inordinate amount of slack in the driveline. With the 550, this has been minimized. The increased clutch friction point helps, but there are other factors that add up to a bike that takes the slow stuff in stride.

And once you break loose of the four-wheeled entanglement, spirited riding can become your forte. Just like the 500 all over again. Action on the twisty roads will surprise the rider who knows CB750s. In fact, on a bender with little in the way of straights, the 550 can say “so long” to the larger model, given equal riders. Its main limitations come in the forms of a low-hanging sidestand on the left, followed by the centerstand tab. On the right, the peg hits first, but pressing on, regardless, will exceed the Bridgestone tires’ limits, so heed the footpeg warning.

We were able to excite the rear shocks' state of nervousness in exceptionally hard going with just a rider aboard; with two in the saddle, the units say "Uncle" a bit sooner. They allow a "wallowing" sensation before the point of peg-dragging whe loaded in this manner. By then, of course, the passenger i throwing hints the rider's way about going a bit too fast-hints > in the form of fingernails clawing at the rib cage.

The front disc brake unit did some squealing and screeching at different times; it didn’t seem to matter whether the unit was hot or cold, but it worked fairly well when dry, at least. In rainy weather, though, much to our amazement, the unit wet-faded. We’ve never had wet weather problems such as this with a disc brake unit, and we hope we never have them again!

The real problem came when the disc was drying out. The brake became overly sensitive and grabby. We wonder if the small plastic shield fitted over the disc to prevent water from being slung onto the rider has anything to do with the problem. Since this way the shield holds the water down where it is again picked up by the disc, the unit never has a chance to rid itself of the water. And yet, on other models we have tested with this same shield feature, the wet-fade problem never occurred.

At the aft end of the machine, rear brake linings have been made less sensitive, and feature a wear indicator so one can see how much of that precious lining is left.

Long excursions will bring out only a few sore spots. One usually turns out to be the rider’s butt; the seat gets uncomfortable after about 100 miles. The Japanese haven’t yet mastered the seat padding end of things. Another item that can be bothersome is the handlebars. They’re too straight up and down for long distances or higher speeds. Lower bars would let the rider crouch forward more, and the wind wouldn’t be so fatiguing. And throw away the grips and get some that don’t chew your hands up. You’ll be much more comfortable.

Might you recognize a 550 if one happened past? Perhaps, if you got a look at the sidecover, where “550 Four” is emblazoned. Otherwise, the new five-and-a-half looks quite a bit like the old 500. Looks, that is. But you’re forgetting about how Honda wanted to make the 550 better, make it more appealing and make it different, but still within a hairsbreadth of the excellent original. Darned if they didn’t do it too.

HONDA

CB550

$ 1671

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAct Sane In Spain Or Don't Get On the Plane

June 1974 -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1974 -

Departments

Departments"Feedback"

June 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

June 1974 By Joe Parkhurst -

Competition

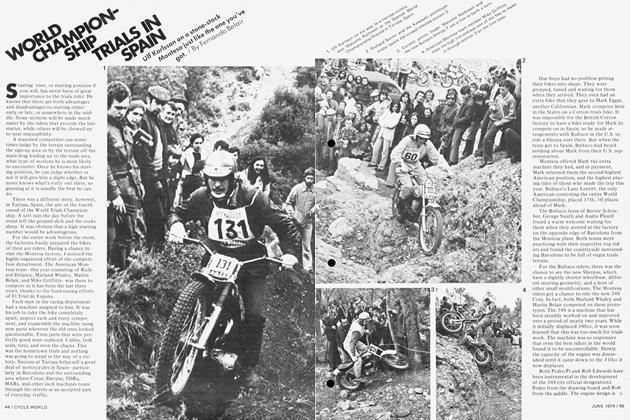

CompetitionWorld Championship Trials In Spain

June 1974 By Fernando Belair -

Features

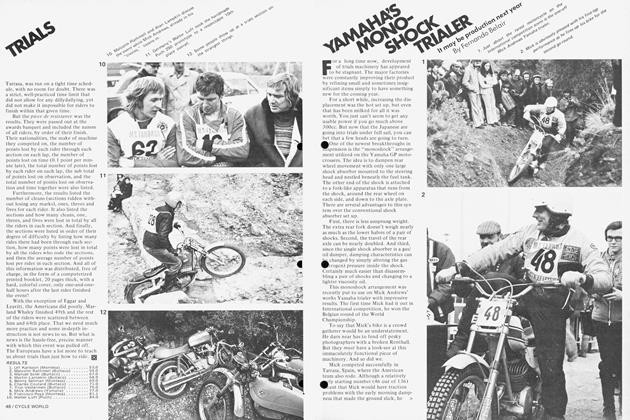

FeaturesYamaha's Monoshock Trialer

June 1974 By Fernando Belair