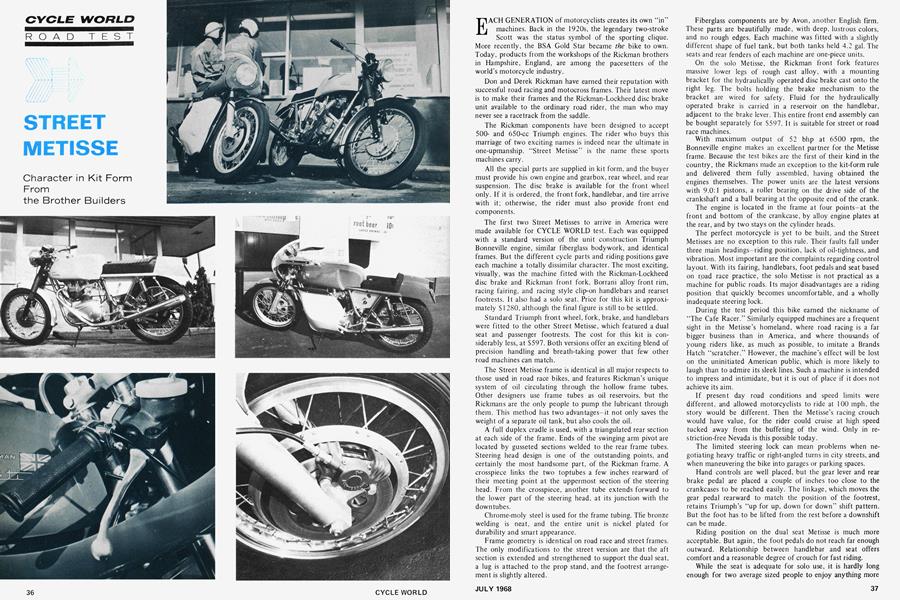

STREET METISSE

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

Character in Kit Form From the Brother Builders

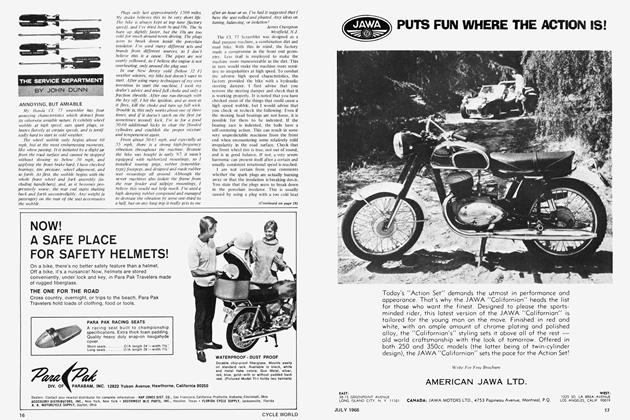

EACH GENERATION of motorcyclists creates its own “in” machines. Back in the 1920s, the legendary two-stroke Scott was the status symbol of the sporting clique. More recently, the BSA Gold Star became the bike to own. Today, products from the workshops of the Rickman brothers in Hampshire, England, are among the pacesetters of the world's motorcycle industry.

Don and Derek Rickman have earned their reputation with successful road racing and motocross frames. Their latest move is to make their frames and the Rickman-Lockheed disc brake unit available to the ordinary road rider, the man who may never see a racetrack from the saddle.

The Rickman components have been designed to accept 500and 650-cc Triumph engines. The rider who buys this marriage of two exciting names is indeed near the ultimate in one-upmanship. “Street Metisse” is the name these sports machines carry.

All the special parts are supplied in kit form, and the buyer must provide his own engine and gearbox, rear wheel, and rear suspension. The disc brake is available for the front wheel only. If it is ordered, the front fork, handlebar, and tire arrive with it; otherwise, the rider must also provide front end components.

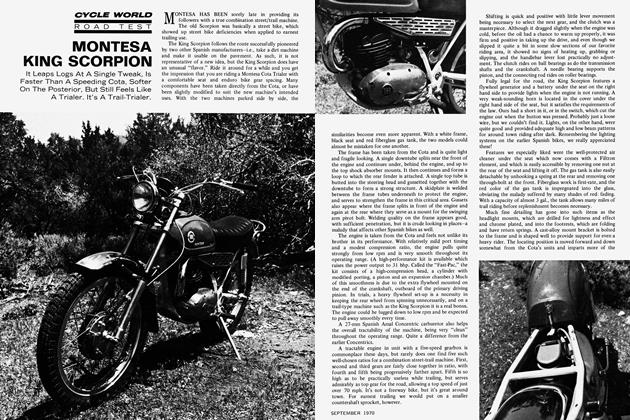

The first two Street Métissés to arrive in America were made available for CYCLE WORLD test. Each was equipped with a standard version of the unit construction Triumph Bonneville engine, similar fiberglass bodywork, and identical frames. But the different cycle parts and riding positions gave each machine a totally dissimilar character. The most exciting, visually, was the machine fitted with the Rickman-Lockheed disc brake and Rickman front fork, Borrani alloy front rim, racing fairing, and racing style clip-on handlebars and rearset footrests. It also had a solo seat. Price for this kit is approximately $1280, although the final figure is still to be settled.

Standard Triumph front wheel, fork, brake, and handlebars were fitted to the other Street Metisse, which featured a dual seat and passenger footrests. The cost for this kit is considerably less, at $597. Both versions offer an exciting blend of precision handling and breath-taking power that few other road machines can match.

The Street Metisse frame is identical in all major respects to those used in road race bikes, and features Rickman’s unique system of oil circulating through the hollow frame tubes. Other designers use frame tubes as oil reservoirs, but the Rickmans are the only people to pump the lubricant through them. This method has two advantages-it not only saves the weight of a separate oil tank, but also cools the oil.

A full duplex cradle is used, with a triangulated rear section at each side of the frame. Ends of the swinging arm pivot are located by gusseted sections welded to the rear frame tubes. Steering head design is one of the outstanding points, and certainly the most handsome part, of the Rickman frame. A crosspiece links the two toptubes a few inches rearward of their meeting point at the uppermost section of the steering head. From the crosspiece, another tube extends forward to the lower part of the steering head, at its junction with the downtubes.

Chrome-moly steel is used for the frame tubing. Tlie bronze welding is neat, and the entire unit is nickel plated for durability and smart appearance.

Frame geometry is identical on road race and street frames. The only modifications to the street version are that the aft section is extended and strengthened to support the dual seat, a lug is attached to the prop stand, and the footrest arrangement is slightly altered.

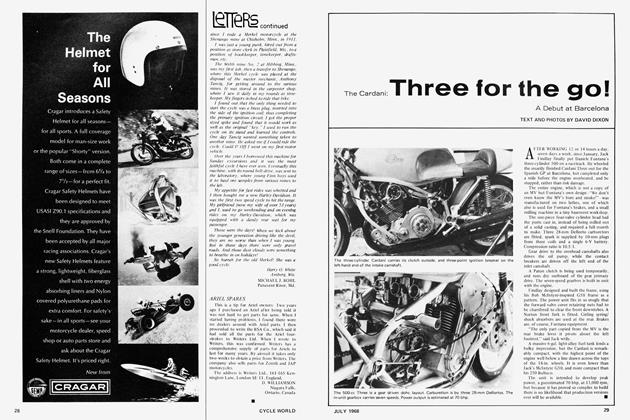

Fiberglass components are by Avon, another English firm. These parts are beautifully made, with deep, lustrous colors, and no rough edges. Each machine was fitted with a slightly different shape of fuel tank, but both tanks held 4.2 gal. The seats and rear fenders of each machine are one-piece units.

On the solo Metisse, the Rickman front fork features massive lower legs of rough cast alloy, with a mounting bracket for the hydraulically operated disc brake cast onto the right leg. The bolts holding the brake mechanism to the bracket are wired for safety. Fluid for the hydraulically operated brake is carried in a reservoir on the handlebar, adjacent to the brake lever. This entire front end assembly can be bought separately for $597. It is suitable for street or road race machines.

With maximum output of 52 blip at 6500 rpm, the Bonneville engine makes an excellent partner for the Metisse frame. Because the test bikes are the first of their kind in the country, the Rickmans made an exception to the kit-form rule and delivered them fully assembled, having obtained the engines themselves. The power units are the latest versions with 9.0:1 pistons, a roller bearing on the drive side of the crankshaft and a ball bearing at the opposite end of the crank.

The engine is located in the frame at four points-at the front and bottom of the crankcase, by alloy engine plates at the rear, and by two stays on the cylinder heads.

The perfect motorcycle is yet to be built, and the Street Métissés are no exception to this rule. Their faults fall under three main headings-riding position, lack of oil-tightness, and vibration. Most important are the complaints regarding control layout. With its fairing, handlebars, foot pedals and seat based on r.oad race practice, the solo Metisse is not practical as a machine for public roads. Its major disadvantages are a riding position that quickly becomes uncomfortable, and a wholly inadequate steering lock.

During the test period this bike earned the nickname of “The Cafe Racer.” Similarly equipped machines are a frequent sight in the Metisse’s homeland, where road racing is a far bigger business than in America, and where thousands of young riders like, as much as possible, to imitate a Brands Hatch “scratcher.” However, the machine’s effect will be lost on the uninitiated American public, which is more likely to laugh than to admire its sleek lines. Such a machine is intended to impress and intimidate, but it is out of place if it does not achieve its aim.

If present day road conditions and speed limits were different, and allowed motorcyclists to ride at 100 mph, the story would be different. Then the Metisse’s racing crouch would have value, for the rider could cruise at high speed tucked away from the buffeting of the wind. Only in restriction-free Nevada is this possible today.

The limited steering lock can mean problems when negotiating heavy traffic or right-angled turns in city streets, and when maneuvering the bike into garages or parking spaces.

Hand controls are well placed, but the gear lever and rear brake pedal are placed a couple of inches too close to the crankcases to be reached easily. The linkage, which moves the gear pedal rearward to match the position of the footrest, retains Triumph’s “up for up, down for down” shift pattern. But the foot has to be lifted from the rest before a downshift can be made.

Riding position on the dual seat Metisse is much more acceptable. But again, the foot pedals do not reach far enough outward. Relationship between handlebar and seat offers comfort and a reasonable degree of crouch for fast riding.

While the seat is adequate for solo use, it is hardly long enough for two average sized people to enjoy anything more than a brief run. A blast of acceleration in the lower gears could even leave the passenger sprawled in the road, while the bike and rider disappear smartly over the horizon!

During performance testing and hard road use, the Bonneville engines showed a tendency to force oil through joints and seals. After only a few days, both bikes required an extensive cleanup. Vibration caused the fairing mount screws to loosen, and a rocker inspection cap to fall off-a common occurrence on Triumph Twins. Fortunately, it could not be felt through the handlebars, seats, or footpegs. The dual seat machine had Triumph’s own rubber mounted handlebar, and bulbous “air cushion’’ grips. The clip-on bars of the solo version clamp directly onto the fork stanchions; even so, vibration was no problem.

The performance of both Street Métissés certainly matches their appearances. For some reason, the engine of the dual seat version refused to turn at more than 6500 rpm, while the solo machine soared quickly to the 7500 rpm mark without hesitation. This, and its fairing, account for the difference in acceleration and speeds between the two bikes.

Handling is where the Metisse frames show their worth. A twisting road is a delight on these bikes, for they can be laid over at extreme angles with confidence. There is no trace of whip or instability, even on bumpy curves. It is only fair to state that the latest Triumph frames also offer excellent handling. In fact, for most purposes, such as touring and city riding, they equal the Metisse units. The occasions when the Rickman product is an advantage occur when the rider has the chance to use really aggressive cornering tactics, or during a long series of curves where the machine has to be flipped from side to side. At such times the Metisse-equipped bike feels as manageable as a 250-cc class machine.

Quarter-mile elapsed time and terminal speed are evidence of the way the solo Street Metisse will streak to 100 mph in a matter of seconds. Modem speed limits mean that, apart from brief and glorious blasts of acceleration, its full potential can never be used. Racetrack testing demonstrated the ability of the Bonneville engine, aided by the fairing, to hold cruising speeds in the 80s and 90s. This engine is also very tractable, with a usable power band from tickover to maximum rpm. Only the limited steering lock handicaps the bike in the city.

The front disc brake is an excellent foil to the bike’s power. Only light finger pressure is needed to reduce speed dramatically. The brake is super-smooth in operation, and is undoubtedly one of the most effective brakes ever fitted to a road motorcycle. Repeated stops from 90-100 mph caused no change in its ability to slow the bike, or lever adjustment.

The dual seat machine possesses the same generous power and flexibility, and is a far better all purpose motorcycle because of its more practical riding position. It was fitted with Triumph’s single leading shoe front brake, and this proved quite adequate, although not as exotic or efficient as the disc unit. Some customers probably will use the new twin leading shoe brake from Triumph.

A comparison between this bike and a standard Triumph Bonneville reveals that the Metisse is approximately 30 lb. lighter. It is also 0.1 mph faster over the quarter, a negligible difference. The weight saving probably explains why the Metisse is 4 mph faster on terminal speed than the Bonneville tested by CYCLE WORLD in 1966. The faired machine is considerably faster than the standard Triumph.

Standard gear ratios are used on both machines. Gear change action is crisp, and the ratios are well chosen. Typical Triumph crunch occurs when low gear is selected from rest. Neutral is easily found, whether the bike is moving or at rest.

Paul Dunstall exhaust pipes and silencers are supplied with the Metisse kits. They emit an exhilarating blare of sound when the engine is working hard, but the noise level is acceptable in the city, providing engine speed is reasonable. The fairing on the solo machine tended to throw noise and heat into the rider’s face, and also prevented cooling air from reaching the engine. Despite the cooling effect of the oil-inthe-frame system, an oil cooler would be an advantage.

On both machines, the oil filler cap is located under the nose of the seat. On the unfaired version, the seat has to be raised to gain access to the filler. This is avoided on the faired bike by a rectangular-shaped cutaway in the seat. Oil level is easily visible through a short section of see-through plastic tubing located on the right rear frame leg. Other useful features are folding footrests, and quick action filler caps on the fuel tanks.

Steen’s Inc., of Alhambra, Calif., supplier of the test bikes, estimates that a competent mechanic should be able to assemble a complete machine in about six hours, once he has wheels and engine and gearbox to fit the kits. The firm also says that a home builder probably will be able to complete the task over a weekend or during a few evenings. A regular flow of the kits will arrive in America, and at the time of the test another eight kits were already on order. Available colors for the fiberglass components are red, British racing green, American racing blue, or desert sand, which is similar to ivory. During the coming months, Steen’s will work on developing a network of Rickman dealerships, so that riders in many parts of the country will be able to order kits without difficulty.

The ingenious Rickman brothers now are working on Street Metisse kits to accept Norton twin-cylinder engines, including the 750s, and BSA A65 engines. They are also contemplating offering kits for, wait for it...the Honda 450 and Suzuki 500/Five! ■

STREET METISSE

$1280