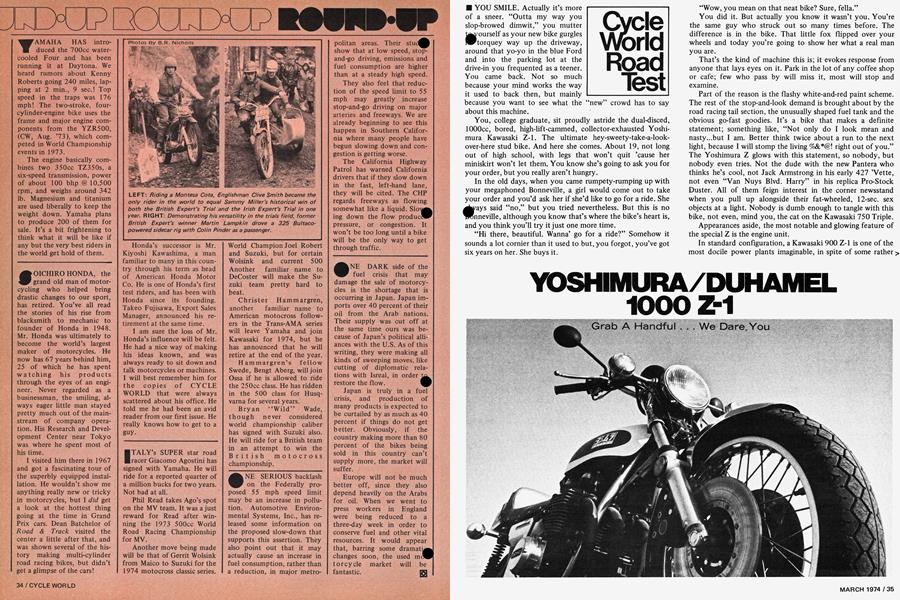

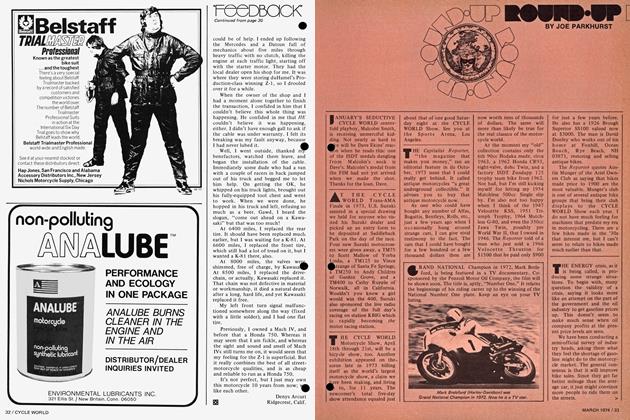

YOSHIMURA/DUHAMEL 1000 Z-1

Cycle World Road Test

YOU SMILE. Actually it's more of a sneer. "Outta my way you slop-browed dimwit," you mutter ourseif as your new bike gurgles torquey way up the driveway, around that yo-yo in the blue Ford and into the parking lot at the drive-in you frequented as a teener. You came back. Not so much because your mind works the way it used to back then, but mainly

because you want to see;hatthe "new" crowd has to say about this machine.

You, college graduate, sit proudly astride the dual-disced, 1000cc, bored, high-lift-cammed, collector-exhausted Yoshi mura Kawasaki Z-1. The ultimate hey-sweety-take-a-look over-here stud bike. And here she comes. About 19, not long out of high school, with legs that won't quit `cause her miniskirt won't let them. You know she's going to ask you for your order, but you really aren't hungry.

In the old days, when you came rumpety-rumpingup with your megaphoned Bonneville, a girl would come out to take your order and you'd ask her if she'd like to go for a ride. She ays said "no," but you tried nevertheless. But this is no nneville, although you know that's where the bike's heart is, and you think you'll try it just one more time.

"Hi there, beautiful. Wanna' go for a ride?" Somehow it sounds a lot cornier than it used to but, you forgot, you've got six years on her. She buys it.

"Wow, you mean on that neat bike? Sure, fella."

You did it. But actually you know it wasn't you. You're the same guy who struck out so many times before. The difference is in the bike. That little fox flipped over your wheels and today you're going to show her what a real man you are.

That's the kind of machine this is; it evokes response from anyone that lays eyes on it. Park in the lot of any coffee shop or cafe; few who pass by will miss it, most will stop and examine.

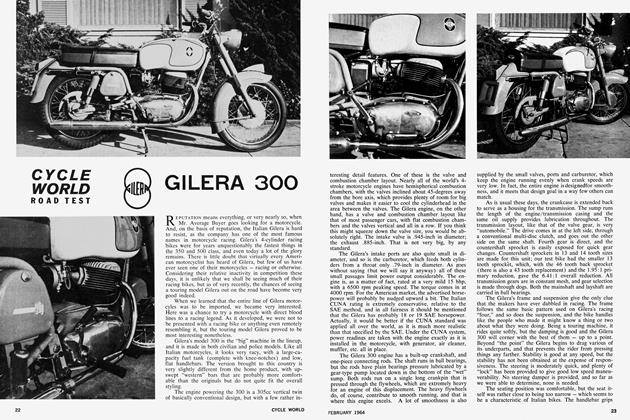

Part of the reason is the flashy white-and-red paint scheme. The rest of the stop-and-look demand is brought about by the road racing tail section, the unusually shaped fuel tank and the obvious go-fast goodies. It's a bike that makes a definite statement; something like, "Not only do I look mean and nasty...but I am. Better think twice about a run to the next light, because I will stomp the living 91c&*@! right out of you." The Yoshimura Z glows with this statement, so nobody, but nobody even tries. Not the dude with the new Pantera who thinks he's cool, not Jack Armstrong in his early 427 `Vette, not even "Van Nuys Blvd. Harry" in his replica Pro-Stock Duster. All of them feign interest in the corner newsstand when you pull up alongside their fat-wheeled, 12-sec. sex objects at a light. Nobody is dumb enough to tangle with this bike, not even, mind you, the cat on the Kawasaki 750 Triple.

Appearances aside, the most notable and glowing feature of the special Z is the engine unit.

In standard configuration, a Kawasaki 900 Z-1 is one of the most docile power plants imaginable, in spite of some rather advanced and unusual design features. First of all, the Z-l features twin overhead camshafts, driven from the crankshaft by a chain located between the center cylinders. The cam lobes operate directly on the valves by pressing on valve top caps, under which are shims to adjust the valve clearance. The lack of rocker arms permits high rpm; 9000 rpm at red line on the standard engine. And that’s with fairly mild cam timing and valve lift.

Flat top pistons in the standard Z-l give a compression ratio of 8.5:1 which allows the machine to run on regular gasoline, and an air/oil separator at the top of the crankcase vents combustion vapors into a plenum chamber which leads them to the air filter and engine, to be re-burned, reducing exhaust emissions (hydrocarbons) by nearly 40 percent.

In spite of its mild state of tune, the Z-l shows some fbatures which are usually associated only with racing machinery. Of interest are the one-piece connecting rods which ride on needle bearings. These are lighter than a conventional two-piece rod and are somewhat narrower in width at the big end. The crankshaft is a pressed together unit comprising nine pieces, supported by six roller main bearings.

Oil for lubricating and cooling the engine and transmission is circulated through a filter and then to the moving parts by a gear-type pump. Because of the abundance of needle and roller, bearings in the highly stressed connecting rods and crankshaft, the oil pressure is very low, in the neighborhood of 6 lb./sq. in.

A total of 7 pt. of oil is carried in a sump at the bottom of the engine which is spread out enough to prevent making the already tall power plant any taller. A convenient sight glass is provided in the side of the clutch cover for visual checking of the oil supply.

A complete road test of a standard Z-l appeared in the Mar. ’73 issue of CW, so we’ll begin discussing the modifications > Yoshimura Racing has made to transform this machine into even more of a stud bike than the stocker.

The name, Y oshimura-duHamel 1000 Z-1, is somewhat of a misnomer because the only parts actually used by duHamel his factory-sponsored Z-1 production bike are the handleba front forks, twin-disc brakes and the instruments. Yoshimura will be producing at least 200 of these machines with only detail modifications to make them legal for AMA production racing.

The most obvious change to the Z-l is the fiberglass work. The seat is very similar to the ones used by the Kawasaki factory road racing team on their H2Rs, except that it is longer and wider in the tail section. Unsnap the seat cover at the rear and you'll find a door in the "hump" where tools and odds and ends may be stored.

Obviously different than the Kawasaki road racing tanks, the Yoshimura's was copied (?) from the aluminum ones used on the AJS 7R and Matchless G-5O racers of the SOs and early 60s. Part of the front was removed, however, to allow the tank to be placed farther forward, giving the rider additional room for his knees.

Also modified is the frame which features a tube welded above the swinging arm pivot between the two nearly vertical tubes. A similar tube is welded between the downtubes in t area of the steering head, and liberal gusseting is present whe the horizontal toptubes come closest to the main toptube (see photo). This material was added in an attempt to reduce the standard Z-l's tendency to wobble slightly under racing conditions. These handling deficiencies become more severe when the engine is modified to produce more power. The frames shown in the photos were nickel plated for appearance reasons, but production frames will be painted black.

The outside of the engine doesn't give one many clues about what's been modified inside. The only obvious differ ence is the 4-into-i collector exhaust system.

When quizzed about why "Pops" designed the collector junction into a square shape (which acts to reduce the machine's ground clearance) rather than blend the four pipes into a collector in a flat plane, Dale Alexander, general manager of Yoshimura Racing, explained that a pipe of that design had been tried, but failed to produce as broad a powerband as the square design.

slightly wilder than stock camshafts permit the Z-1 to idle relatively smoothly at 1200 rpm, but there's the characteris~ "lumpy" sound which is associated with modified camshafts. Surprisingly enough, "Pops" made no changes to the carbure tors or to the cylinder heads for reasons we'll discuss later

The increase in engine displacement from 903cc to 984cc was achieved by fitting pistons 2.5mm larger than standard. It would have been possible to bore the Z-l out even farther, but "Pops" calculated that any further increase in piston size would not benefit performance because the combustion chambers are unable to flow any more air without extensive modifications.

Yoshimura is relatively unconcerned about running as high a compression ratio as possible. He begins with special pistons made to his specifications with a fairly high dome and starts removing material from the dome and running dynamometer tests. He continues his tests until the engine produces maximum power, and is relatively nonchalant about what compression ratio he finally winds up with.

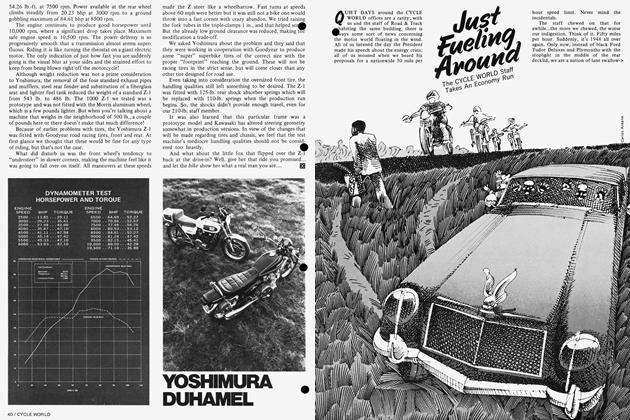

Tests on the Webco dynamometer confirmed our conclu sions: the Yoshimura-duHamel Z-1 has one of the broadest torque curves and the highest horsepower output of any strel legal machine we've ever tested! The torque stays above 40 lb.-ft. from 3700 rpm to 10,200 rpm with a maximum of 54.26 lb.-ft. at 7500 rpm. Power available at the rear wheel climbs steadily from 20.23 bhp at 3000 rpm to a ground gobbling maximum of 84.61 bhp at 8500 rpm.

YOSHIMURA/DUHAMEL

1000 Z-1

SPECI FICATIONS

List price $2950

The engine continues to produce good horsepower until 10,000 rpm, where a significant drop takes place. Maximum safe engine speed is 10,500 rpm. The power delivery is so progressively smooth that a transmission almost seems superfluous. Riding it is like turning the rheostat on a giant electric motor. The only indication of just how fast you are suddenly going is the visual blur at your sides and the strained effort to keep from being blown right off the motorcycle!

Although weight reduction was not a prime consideration to Yoshimura, the removal of the four standard exhaust pipes and mufflers, steel rear fender and substitution of a fiberglass seat and lighter fuel tank reduced the weight of a standard Z-l from 543 lb. to 486 lb. The 1000 Z-l we tested was a prototype and was not fitted with the Morris aluminum wheel, which is a few pounds lighter. But when you’re talking about a machine that weighs in the neighborhood of 500 lb., a couple of pounds here or there doesn’t make that much difference!

Because of earlier problems with tires, the Yoshimura Z-l was fitted with Goodyear road racing tires, front and rear. At first glance we thought that these would be fine for any type of riding, but that’s not the case.

What did disturb us was the front wheel’s tendency to “understeer” in slower corners, making the machine feel like it was going to fall over on itself. All maneuvers at these speeds made the Z steer like a wheelbarrow. Fast turns at speeds above 60 mph were better but it was still not a bike one would throw into a fast corner with crazy abandon. We tried raising the fork tubes in the triple-clamps 1 in., and that helped soi^fc But the already low ground clearance was reduced, making me modification a trade-off.

We asked Yoshimura about the problem and they said that they were working in cooperation with Goodyear to produce some “super” superbike tires of the correct size with the proper “footprint” reaching the ground. These will not be racing tires in the strict sense, but will come closer than any other tire designed for road use.

Even taking into consideration the oversized front tire, the handling qualities still left something to be desired. The Z-l was fitted with 125-lb. rear shock absorber springs which will be replaced with 110-lb. springs when the production run begins. So, the shocks didn’t provide enough travel, even for our 210-lb. staff member.

It was also learned that this particular frame was a prototype model and Kawasaki has altered steering geometry somewhat in production versions. In view of the changes that will be made regarding tires and chassis, we feel that the test machine’s mediocre handling qualities should not be considered too heavily. ^

And what about the little fox that flipped over the Z-l back at the drive-in? Well, give her that ride you promised... and let the bike show her what a real man you are.... |5

View Full Issue

View Full Issue