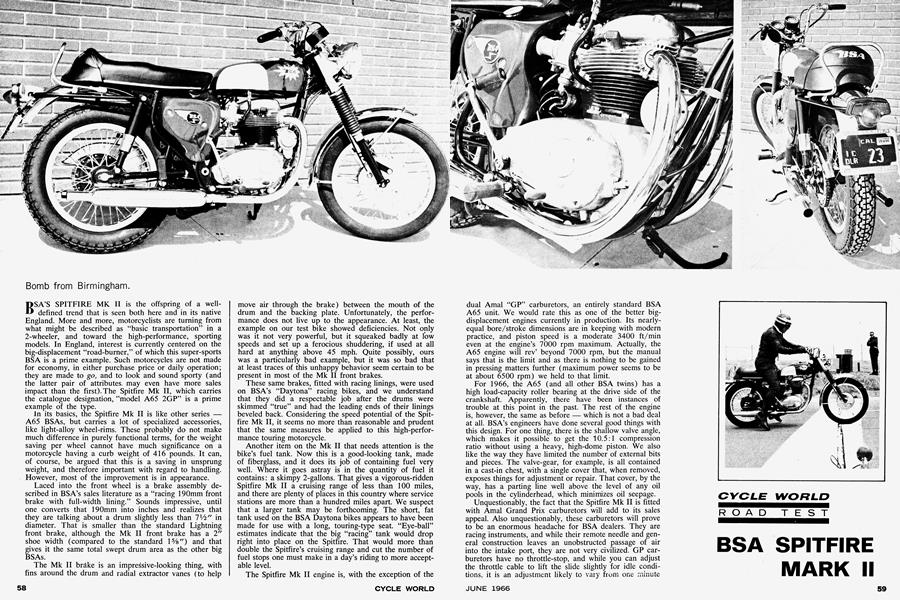

Bomb from Birmingham.

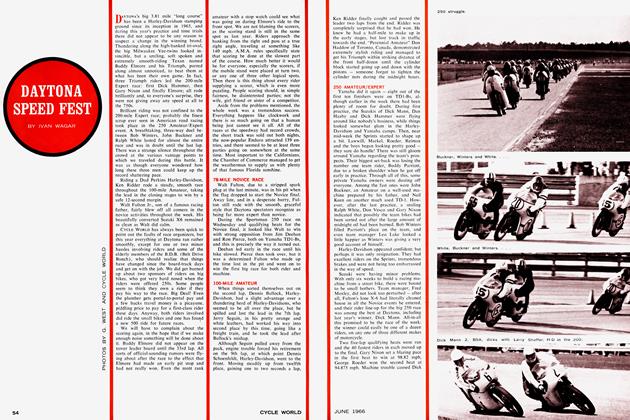

BSA’S SPITFIRE MK II is the offspring of a welldefined trend that is seen both here and in its native England. More and more, motorcyclists are turning from what might be described as “basic transportation” in a 2-wheeler, and toward the high-performance, sporting models. In England, interest is currently centered on the big-displacement “road-burner,” of which this super-sports BSA is a prime example. Such motorcycles are not made for economy, in either purchase price or daily operation; they are made to go, and to look and sound sporty (and the latter pair of attributes may even have more sales impact than the first).The Spitfire Mk II, which carries the catalogue designation, “model A65 2GP” is a prime example of the type.

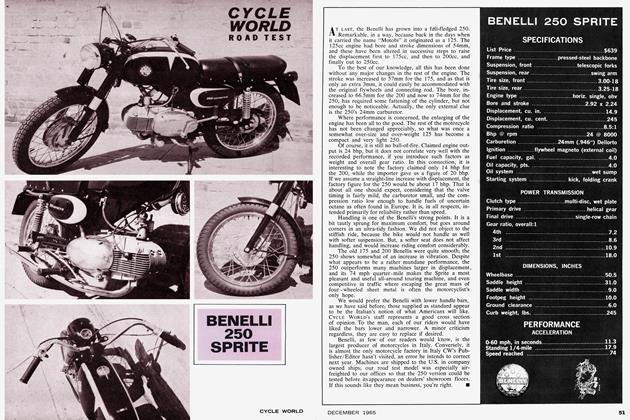

In its basics, the Spitfire Mk II is like other series — A65 BSAs, but carries a lot of specialized accessories, like light-alloy wheel-rims. These probably do not make much difference in purely functional terms, for the weight saving per wheel cannot have much significance on a motorcycle having a curb weight of 416 pounds. It can, of course, be argued that this is a saving in unsprung weight, and therefore important with regard to handling. However, most of the improvement is in appearance.

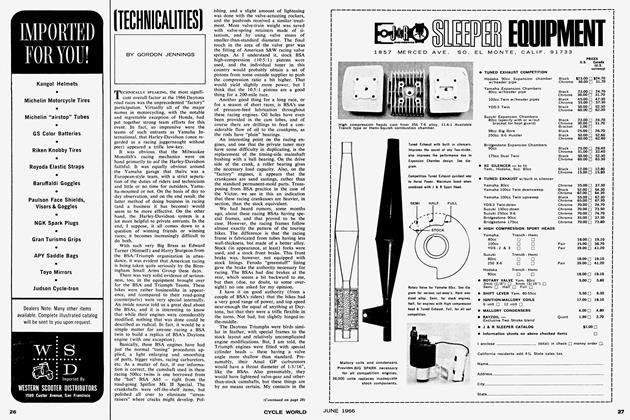

Laced into the front wheel is a brake assembly described in BSA’s sales literature as a “racing 190mm front brake with full-width lining.” Sounds impressive, until one converts that 190mm into inches and realizes that they are talking about a drum slightly less than IVi" in diameter. That is smaller than the standard Lightning front brake, although the Mk II front brake has a 2" shoe width (compared to the standard 1%") and that gives it the same total swept drum area as the other big BSAs.

The Mk II bráke is an impressive-looking thing, with fins around the drum and radial extractor vanes (to help move air through the brake) between the mouth of the drum and the backing plate. Unfortunately, the performance does not live up to the appearance. At least, the example on our test bike showed deficiencies. Not only was it not very powerful, but it squeaked badly at low speeds and set up a ferocious shuddering, if used at all hard at anything above 45 mph. Quite possibly, ours was a particularly bad example, but it was so bad that at least traces of this unhappy behavior seem certain to be present in most of the Mk II front brakes.

These same brakes, fitted with racing linings, were used on BSA’s “Daytona” racing bikes, and we understand that they did a respectable job after the drums were skimmed “true” and had the leading ends of their linings beveled back. Considering the speed potential of the Spitfire Mk II, it seems no more than reasonable and prudent that the same measures be applied to this high-performance touring motorcycle.

Another item on the Mk II that needs attention is the bike’s fuel tank. Now this is a good-looking tank, made of fiberglass, and it does its job of containing fuel very well. Where it goes astray is in the quantity of fuel it contains : a skimpy 2-gallons. That gives a vigorous-ridden Spitfire Mk II a cruising range of less than 100 miles, and there are plenty of places in this country where service stations are more than a hundred miles apart. We suspect that a larger tank may be forthcoming. The short, fat tank used on the BSA Daytona bikes appears to have been made for use with a long, touring-type seat. “Eye-ball” estimates indicate that the big “racing” tank would drop right into place on the Spitfire. That would more than double the Spitfire’s cruising range and cut the number of fuel stops one must make in a day’s riding to more acceptable level.

The Spitfire Mk II engine is, with the exception of the dual Amal “GP” carburetors, an entirely standard BSA A65 unit. We would rate this as one of the better bigdisplacement engines currently in production. Its nearlyequal bore/stroke dimensions are in keeping with modern practice, and piston speed is a moderate 3400 ft/min even at the engine’s 7000 rpm maximum. Actually, the A65 engine will rev’ beyond 7000 rpm, but the manual says that is the limit and as there is nothing to be gained in pressing matters further (maximum power seems to be at about 6500 rpm) we held to that limit.

BSA SPITFIRE MARK II

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

For 1966, the A65 (and all other BSA twins) has a high load-capacity roller bearing at the drive side of the crankshaft. Apparently, there have been instances of trouble at this point in the past. The rest of the engine is, however, the same as before — which is not a bad deal at all. BSA’s engineers have done several good things with this design. For one thing, there is the shallow valve angle, which makes it possible to get the 10.5:1 compression ratio without using a heavy, high-dome piston. We also like the way they have limited the number of external bits and pieces. The valve-gear, for example, is all contained in a cast-in chest, with a single cover that, when removed, exposes things for adjustment or repair. That cover, by the way, has a parting line well above the level of any oil pools in the cylinderhead, which minimizes oil seepage.

Unquestionably, the fact that the Spitfire Mk II is fitted with Amal Grand Prix carburetors will add to its sales appeal. Also unquestionably, these carburetors will prove to be an enormous headache for BSA dealers. They are racing instruments, and while their remote needle and general construction leaves an unobstructed passage of air into the intake port, they are not very civilized. GP carburetors have no throttle-stop, and while you can adjust the throttle cable to lift the slide slightly for idle conditions, it is an adjustment likely to vary from one minute to the next. Also, the distance from the needle-jet to the spray nozzle in the carburetor throat gives rather poor low-speed throttle response. Whack on too much throttle at low engine speeds and the engine dies. The touringtype Monobloc carburetor is in every respect except pure horsepower a better instrument. Certainly, the Monoblocequipped BSA Lightning (with the same throat diameters as the GP carburetors) is an easier-starting, smootherrunning motorcycle.

Another point to consider is that the Spitfire Mk II, with its GP carburetors, must be fitted with a remote floatchamber — and the arrangement provided is not entirely satisfactory. Amal’s current series of small, flat remotemounting float chambers have a pivoted float, acting on the fuel needle-valve via a lever. These float chambers have proven to be very sensitive to vibration. Hit them with just the right frequency and amplitude, and fuel ceases to flow. The Spitfire Mk II shows distinct signs of suffering from that trouble. The engine is plagued with mysterious flat-spots. One of these, at just under 6000 rpm, is especially severe, and the engine will barely pull through it when hauling against 4th gear. Plug readings, taken after a “chop” at 6000 rpm in 4th, show a lean condition, and there is a pronounced surging at that combination of load and engine speed. Accelerating through the gears, the engine passes through the “dry” stage so quickly that it cannot be felt, but the effect must certainly be there.

Most of this is, we think, due to the float-chamber mounting. It is offset, in the frame, and very near the left-hand carburetor. Consequently, the extremely short fuel-line on that side (the lines are made of a relativelyhard plastic) is virtually a rigid strut, transmitting engine vibration directly from the carburetor to the chamber. It is a phenomenon well-known to experienced road-racing tuners. The cure is to re-mount the chamber and use soft neoprene fuel-lines. If the BSA factory does not get around to this, we would recommend the modification to anyone who buys a Spitfire Mk II.

Our test bike was decidely snappish about starting, but we found that the tendency to bite-back was greatly reduced by keeping the throttle all but shut while kicking it through. With this treatment, it became quite willing to start when warm; although it remained touchy about coming to life on cool mornings.

The Spitfire Mk II is most pleasant at highway cruising speeds. Like all of the big BSAs, it vibrates very little, and it is nicely responsive to big, sudden applications of throttle when humming along at 60 mph in 4th-cog. The seating position is comfortable, and the controls (as we journalists are wont to say) “fall readily to the hand — or foot.” The matched tach’ and speedometer are well positioned, but neither are very accurate at the high end of the scale. The speedometer actually reads a trifle slow up to about 80 mph, and then becomes more and more optimistic as the speed climbs. The tachometer is quite accurate to 5000 rpm, but gains 250 rpm at 6000, and an indicated 7000 rpm is actually 6640 rpm.

In the handling department, the Spitfire is undistinguished by anything but steadiness. It is neither quickhandling or sluggish; just very stable, an attribute likely to please the average rider. More important is the bike’s exceptionally comfortable ride. Over most surfaces it gliiiiides along, without jouncing from springs and damping being too harsh, or the hobby-horse effect one gets when a suspension is too soft.

Finish has long been a BSA strong-point, and our test bike was an exception only because it had been marred by sundry oil leaks around the crankcase and because its battery had “boiled” over. Otherwise it was great, with slathers of chrome and polished aluminum alloy. Now, if BSA would only add a 4-gallon tank, 8-inch front brake and 1 5/32" Monobloc carburetors — but then that would be a BSA Lightning, wouldn’t it?

BSA

SPITFIRE MK II

SPECIFICATIONS

$1429

PERFORMANCE