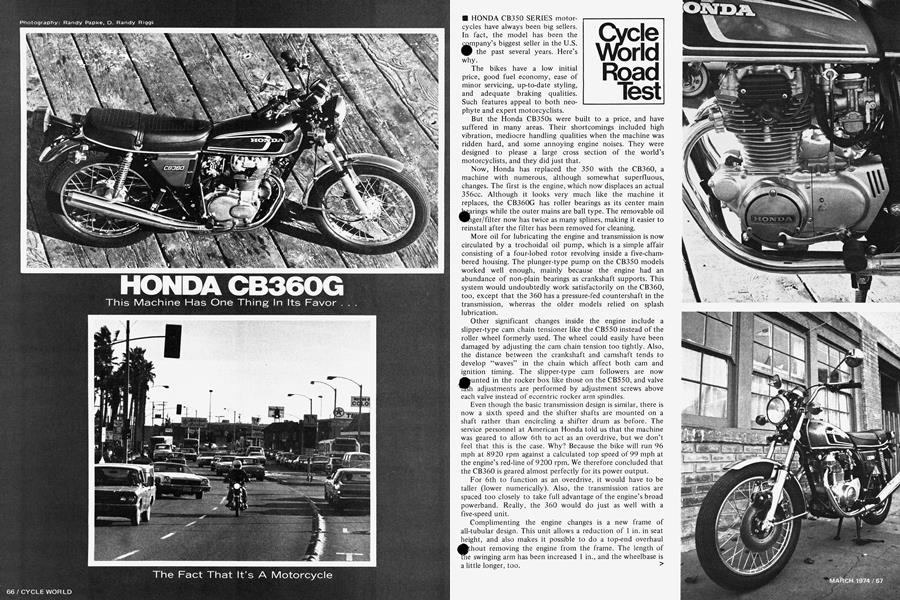

HONDA CB360G

This Machine Has One Thing In Its Favor...

Cycle World Road Test

• HONDA CB3SO SERIES motor cycles have always been big sellers. In fact, the model has been the mpany's biggest seller in the U.S. the past several years. Here's why.

The bikes have a low initial price, good fuel economy, ease of minor servicing, up-to-date styling, and adequate braking qualities. Such features appeal to both neo phyte and expert motorcyclists.

But the Honda CB350s were built to a price, and have suffered in many areas. Their shortcomings included high vibration, mediocre handling qualities when the machine was ridden hard, and some annoying engine noises. They were designed to please a large cross section of the world’s motorcyclists, and they did just that.

Now, Honda has replaced the 350 with the CB360, a machine with numerous, although somewhat superfluous, changes. The first is the engine, which now displaces an actual 356cc. Although it looks very much like the machine it replaces, the CB360G has roller bearings as its center main J^arings while the outer mains are ball type. The removable oil Aliger/filter now has twice as many splines, making it easier to reinstall after the filter has been removed for cleaning.

More oil for lubricating the engine and transmission is now circulated by a trochoidal oil pump, which is a simple affair consisting of a four-lobed rotor revolving inside a five-chambered housing. The plunger-type pump on the CB350 models worked well enough, mainly because the engine had an abundance of non-plain bearings as crankshaft supports. This system would undoubtedly work satisfactorily on the CB360, too, except that the 360 has a pressure-fed countershaft in the transmission, whereas the older models relied on splash lubrication.

Other significant changes inside the engine include a slipper-type cam chain tensioner like the CB550 instead of the roller wheel formerly used. The wheel could easily have been damaged by adjusting the cam chain tension too tightly. Also, the distance between the crankshaft and camshaft tends to develop “waves” in the chain which affect both cam and ignition timing. The slipper-type cam followers are now ^fcunted in the rocker box like those on the CB550, and valve ^Rh adjustments are performed by adjustment screws above each valve instead of eccentric rocker arm spindles.

Even though the basic transmission design is similar, there is now a sixth speed and the shifter shafts are mounted on a shaft rather than encircling a shifter drum as before. The service personnel at American Honda told us that the machine was geared to allow 6th to act as an overdrive, but we don’t feel that this is the case. Why? Because the bike will run 96 mph at 8920 rpm against a calculated top speed of 99 mph at the engine’s red-line of 9200 rpm. We therefore concluded that the CB360 is geared almost perfectly for its power output.

For 6th to function as an overdrive, it would have to be taller (lower numerically). Also, the transmission ratios are spaced too closely to take full advantage of the engine’s broad powerband. Really, the 360 would do just as well with a five-speed unit.

Complimenting the engine changes is a new frame of all-tubular design. This unit allows a reduction of 1 in. in seat height, and also makes it possible to do a top-end overhaul Ehout removing the engine from the frame. The length of íe swinging arm has been increased 1 in., and the wheelbase is a little longer, too. >

However, the 360 doesn’t seem as sure-footed as its predecessor. The new frame is quite possibly less immune to flexing than the older one, due to its weaker supports in the area of the steering head and rearward (the CB350 featurec^^ pressed-steel backbone design).

Unfortunately, poor rear shock absorbers make the handling situation even worse. The shocks have an inadequate amount of rebound damping which adds to the wallowing effect one gets while sweeping through turns at speed, regardless of where the shock absorber springs are set.

The front forks are a little on the stiff side, causing a fairly harsh ride, especially on older highway sections. For shorter hops across town, however, this situation isn’t nearly as objectionable.

The CB360 isn’t as coldblooded as some models in Honda’s line-up, but the starting procedure is a bit odd. The engine will not start and continue to run with the choke fully on, so the rider has to fiddle with the throttle and the choke opening to get the engine running.

Once warmed up and underway, the 360 feels much like its predecessor in that large amount of vibration are still there. It comes through the handlebar grips (which are the hard plastic items we’ve been complaining about for some time), and the tingling your feet get through the footpegs tends to put tho^k to sleep on a long trip. There is no particular point in t^r engine’s rpm range where the vibration becomes intolerable; it’s just there all the time.

Engine and exhaust noises are low, and the crankcase is now ventilated into the air cleaner in an effort to reduce pollution. Also new is the two-cable push/pull throttle arrangement (like that found on four-cylinder Honda models), and linkage between the carburetors which practically eliminates the need to synchronize the carburetors at each tune-up. The carburetors themselves are the popular Keihin CV (constant vacuum) units which have slides that rise according to the amount of throttle opening registered at the butterflies. This makes it practically impossible to flood the engine by over-ambitious throttle blipping.

But the sensitivity of these carburetors, in addition to a sloppy drive train, makes the CB360G difficult to ride smoothly at slow speeds. Most of the problem lies with the rubber cushion blocks in the rear wheel which separate it from the rear sprocket. They are placed there to increase the life of the rear chain and transmission components by absorbi^J^ some of the shock produced by lugging the engine down in too ' high a gear for the road speed, and by improper or sloppy gear shifting on the part of the rider. A good idea, to be sure, but the 360’s blocks are too soft, acting more like springs than dampers. The net result is that opening and closing the throttle even slightly at slow speeds results in a jerky ride that even an experienced rider cannot smooth out.

Due to the transmission’s improved design and lubrication method, and the abolishment of the remote linkage previously used on CB350 models, moving the gearshift lever results in smoother shifts. Clutch lever pressure is typically Hondalight, but with some occasional chattering when pulling away from a stop.

The CB360G’s controls brought out mixed emotions from our staff members. Most were satisfied with the seat-handlebar-footpeg relationship, although one staffer complained that the footpegs are too far forward. The clutch and brake levers are pinned to prevent them from being lowered on the handlebars, although you can raise them straight up if you want to! Honda is getting the jump on imminent Fedei«P government standards and has placed all handlebar switches so that they can be activated without the rider removing his>

HONDA

CB360G

ECIFICATIONS

Lf~t price $999

hand(s) from the handlebars. Only one criticism here: high/low beam switch is located to the extreme inside of iw left handlebar control assembly and on a line horizontal with the horn button. It’s a virtually unacceptable spot since it’s impossible to operate the high/low beam switch without taking one’s hand partway off the grip. Very poor.

An innovation is the front turn signals,which act as running lights by staying on anytime the lights are on low beam. This is a good feature because it assures the oncoming motorist that a motorcycle, not a car with one inoperative headlight, is approaching. We wish that the rear turn signals did the same, and applaud the choice of amber lenses on the rear turn signals instead of the red lenses found on many machines.

Another fine idea is the lane-change detent in the turn signal switch which starts the turn signals working as soon as the button is moved in the desired direction. Release the button and the turn signal goes off without the need to manually push the switch back to the middle (off) position.

Our test machine was fitted with a front disc brake, available for a paltry $36 more than the drum brake. On a one-stop basis a properly adjusted drum brake will stop^^ almost as short a distance as the disc, but discs are practically immune to fade and provide progressive braking commensurate with the amount of lever pressure applied. This is one of the best features of the machine and is well worth the small amount of extra money it costs.

Also improved is the headlight which now features a more powerful 50/35 watt sealed beam unit, replacing the 35/25 watt unit previously used.

Long distance trips are not the CB360G’s forte. Relatively high vibration, and a hard seat, lower the comfort level considerably. The rear footpegs have been raised because the mufflers are rakishly (and attractively) upswept and are too high for all but the shortest passengers. Consequently, CB360 models are better suited to commuter and short-haul pleasure riders.

Now for the final question. Is the CB360G a better machine than its predecessor? In terms of reliability, it probably is, due to the numerous engine improvements. But it certainly doesn’t handle as well—it has an extra gear it didn’t need, it vibrates with abandon, and it is not overly comfortable. Add to tl^^ the increased cost, and the verdict is a motorcycle with less consumer appeal than the original. SI

View Full Issue

View Full Issue