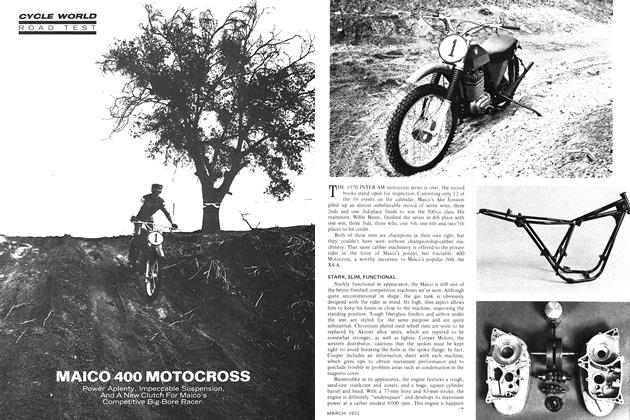

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

MANY MOTORCYCLES have their counterparts in the automotive world — the temperamental, expensive but very fast types, the comfortable and quiet long-distance tourers. Well, then, why not a two-wheel counterpart for the funny little car that is always the same while constantly improving. If ever there was a motorcycle that could be considered to remain the same, year after year, while constantly improving, it would be the Triumph Tiger Cub.

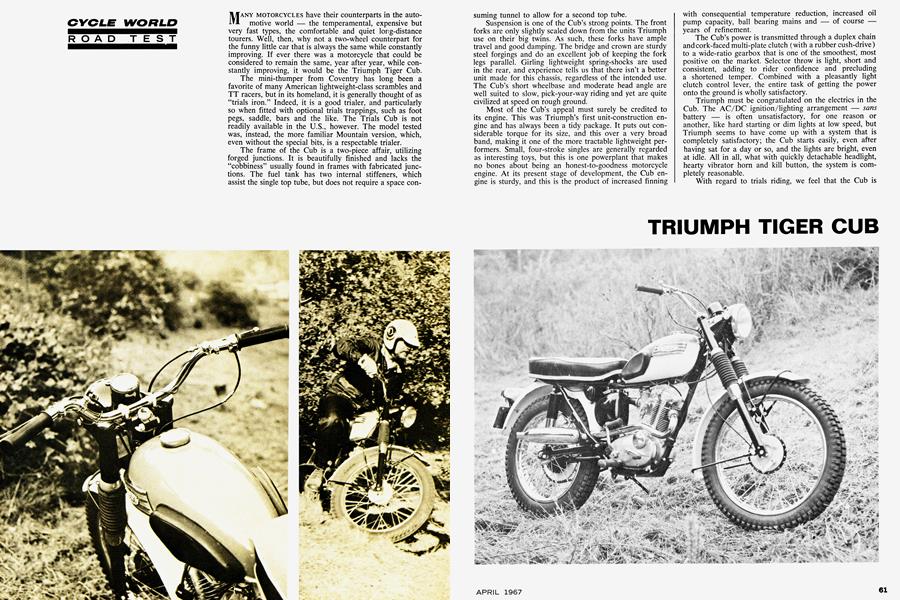

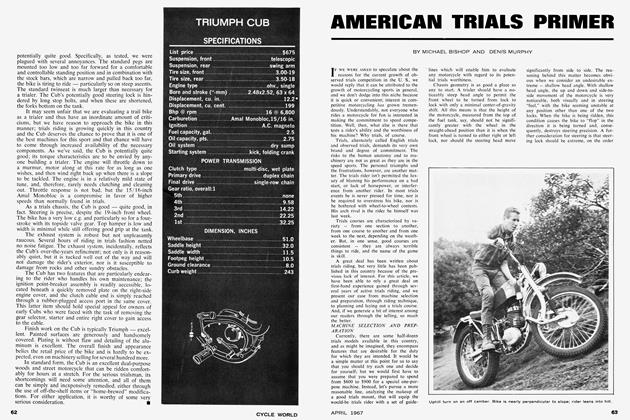

The mini-thumper from Coventry has long been a favorite of many American lightweight-class scrambles and TT racers, but in its homeland* it is generally thought of as “trials iron.” Indeed, it is a good trialer, and particularly so when fitted with optional trials trappings, such as foot pegs, saddle, bars and the like. The Trials Cub is not readily available in the U.S., however. The model tested was, instead, the more familiar Mountain version, which, even without the special bits, is a respectable trialer.

The frame of the Cub is a two-piece affair, utilizing forged junctions. It is beautifully finished and lacks the “cobbiness” usually found in frames with fabricated junctions. The fuel tank has two internal stiffeners, which assist the single top tube, but does not require a space consuming tunnel to allow for a second top tube.

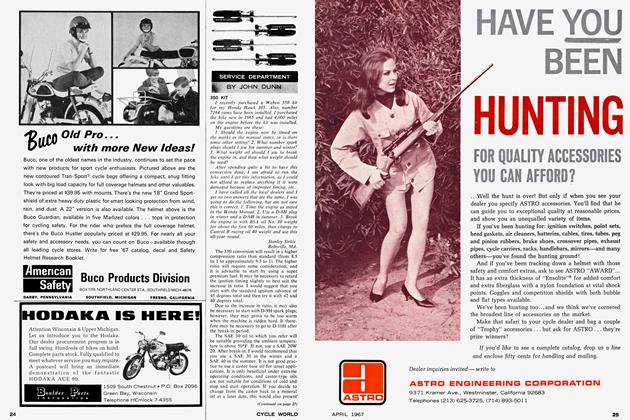

TRIUMPH TIGER CUB

Suspension is one of the Cub’s strong points. The front forks are only slightly scaled down from the units Triumph use on their big twins. As such, these forks have ample travel and good damping. The bridge and crown are sturdy steel forgings and do an excellent job of keeping the fork legs parallel. Girling lightweight spring-shocks are used in the rear, and experience tells us that there isn’t a better unit made for this chassis, regardless of the intended use. The Cub’s short wheelbase and moderate head angle are well suited to slow, pick-your-way riding and yet are quite civilized at speed on rough ground.

Most of the Cub’s appeal must surely be credited to its engine. This was Triumph’s first unit-construction engine and has always been a tidy package. It puts out considerable torque for its size, and this over a very broad band, making it one of the more tractable lightweight performers. Small, four-stroke singles are generally regarded as interesting toys, but this is one powerplant that makes no bones about being an honest-to-goodness motorcycle engine. At its present stage of development, the Cub engine is sturdy, and this is the product of increased finning with consequential temperature reduction, increased oil pump capacity, ball bearing mains and — of course — years of refinement.

The Cub’s power is transmitted through a duplex chain and cork-faced multi-plate clutch (with a rubber cush-drive) to a wide-ratio gearbox that is one of the smoothest, most positive on the market. Selector throw is light, short and consistent, adding to rider confidence and precluding a shortened temper. Combined with a pleasantly light clutch control lever, the entire task of getting the power onto the ground is wholly satisfactory.

Triumph must be congratulated on the electrics in the Cub. The AC/DC ignition/lighting arrangement — sans battery — is often unsatisfactory, for one reason or another, like hard starting or dim lights at low speed, but Triumph seems to have come up with a system that is completely satisfactory; the Cub starts easily, even after having sat for a day or so, and the lights are bright, even at idle. All in all, what with quickly detachable headlight, hearty vibrator horn and kill button, the system is completely reasonable.

With regard to trials riding, we feel that the Cub is potentially quite good. Specifically, as tested, we were plagued with several annoyances. The standard pegs are mounted too low and too far forward for a comfortable and controllable standing position and in combination with the stock bars, which are narrow and pulled back too far, the bike is tiring to ride — particularly so on steep ascents. The standard twinseat is much larger than necessary for a trialer. The Cub’s potentially good steering lock is hindered by long stop bolts, and when these are shortened, the forks bottom on the tank.

It may seem unfair that we are evaluating a trail bike as a trialer and thus have an inordinate amount of criticisms, but we have reason to approach the bike in this manner; trials riding is growing quickly in this country and the Cub deserves the chance to prove that it is one of the best machines for this sport and that chance will have to come through increased availability of the necessary components. As we’ve said, the Cub is potentially quite good; its torque characteristics are to be envied by anyone building a trialer. The engine will throttle down to a murmur, motor along at this rate for as long as one wishes, and then wind right back up when there is a slope to be tackled. The engine is in a relatively mild state of tune, and, therefore, rarely needs clutching and cleaning out. Throttle response is not bad, but the 15/16-inch Amal Monobloc is a compromise in favor of higher speeds than normally found in trials.

As a trials chassis, the Cub is good — quite good, in fact. Steering is precise, despite the 19-inch front wheel. The bike has a very low c.g. and particularly so for a fourstroke with its topside valve gear. Top hamper is low and width is minimal while still offering good grip at the tank.

The exhaust system is robust but not unpleasantly raucous. Several hours of riding in trials fashion netted no noise fatigue. The exhaust system, incidentally, reflects the Cub’s over-the-years refinement; not only is it reasonably quiet, but it is tucked well out of the way and will not damage the rider’s exterior, nor is it susceptible to damage from rocks and other sundry obstacles.

The Cub has two features that are particularly endearing to the rider who handles his own maintenance; the ignition point-breaker assembly is readily accessible, located beneath a quickly removed plate on the right-side engine cover, and the clutch cable end is simply reached through a rubber-plugged access port in the same cover. This latter item should hold special appeal for owners of early Cubs who were faced with the task of removing the gear selector, starter and entire right cover to gain access to the cable.

Finish work on the Cub is typically Triumph — excellent. Painted surfaces are generously and handsomely covered. Plating is without flaw and detailing of the aluminum is excellent. The overall finish and appearance belies the retail price of the bike and is hardly to be expected, even on machinery selling for several hundred more.

In standard form, the Cub is an excellent dual-purpose woods and street motorcycle that can be ridden comfortably for hours at a stretch. For the serious trialsman, its shortcomings will need some attention, and all of them can be simply and inexpensively remedied, either through the use of off-the-shelf items or “home-brewed” modifications. For either application, it is worthy of some very serious consideration.

TRIUMPH

CUB

$675