Moorland Meyhem

A History Of The Scott Trial

Simon Read

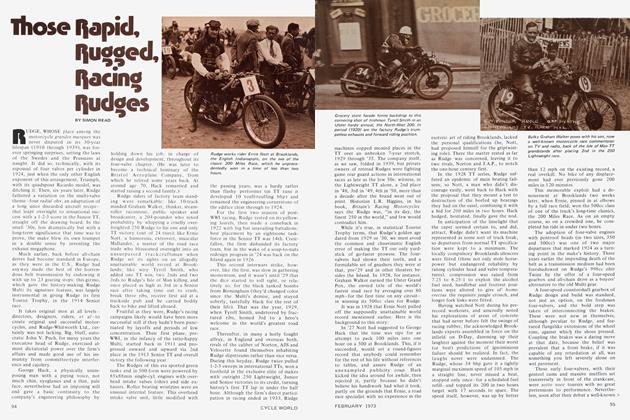

FREETHINKING Alfred Angus Scott, father of the water-cooled, two-cylinder, two-stroke, two-speed motorcycle that made his name a byword within and without his native Britain, shared Carcycle’s belief that “the English are a dumb people.” In particular, he claimed, they had a dent where their bump of locality should be, resulting in a propensity for getting lost and an inability to navigate even with the aid of maps, once they quit main roads.

A Scotsman by descent, though born and raised in England, at Bradford, Yorkshire, Scott developed this theme in conversation with some English associates early in 1914. To prove his point, he offered to plan a 90-mile moorland course for a trial to end all trials, in which competitors would be issued route-marked maps but denied all other aids: no thisaway/thataway arrows, no observed section placards, no dye.

(Editor’s Note: Run under rules that have counterparts in Ireland but not elsewhere in England, the notorious Scott Trial is effectively a race and a trial rolled up in one. Here is how the system works:

Standard Time, by official definition, is “the time taken by the driver who completes the course in the shortest time. ” The “driver” concerned is unpenalized in respect to speed, while slower competitors are debited one mark for every two minutes or part of two minutes by which their time exceeds Standard Time.

On observed sections, marks are docked on the familiar 0-1-3-5 basis, i.e. none for a clean traversal, 1 for footing once, 3 for footing twice or of tener, 5 for failing.

Placings are finally determined by totaling penalty marks of both classes. The “driver” with the least penalty marks is the winner. In the event of a tie, the decision goes to whoever “progresses the furthest clean and then loses the least number of marks on observation. ”)

His bikes being then in their production infancy (manufacture had started only five years earlier), they still had plenty of bugs left in them. Scott, with his double endowment of Scots/Yorkshire shrewdness, recognized this and accordingly restricted his Scott Trial field to Scott mounted employees of his own factory at Saltaire, in Yorkshire’s West Riding, and of the make’s main dealer, Eric Myers, of nearby Bradford. Entry was by invitation only.

So on March 15, 1914, a date forever etched in English roughriding annals, the skirling of the exhausts of 14 embattled stroker Twins rent the welkin above Wharfedale and Nidderdale. To minimize riders’ leisure for studying their route maps, Scott and his collaborators had included terrain of extreme machine deranging and antipersonnel potential. According to The Motor Cycle, this was “probably the most severe competition ever held,” and it founded a series that has outlived its sire by almost a half century, surviving today in an ameliorated form.

Dumb as the English may have been in the year 1914, though, nine out of the 14 starters belied Scott’s they’ll-getlost prediction and made it to the finish, albeit in a state of advanced exhaustion and with most disintegral bits of their bikes lost beyond recall on remote moorland heights or in the beds of valley streams. At one river crossing alone, “every rider came to a stop with the whole of his engine, magneto and carburetor under water.”

Marks were deducted for loss of parts from, or enroute damage to, machines, also for late arrival at the finish. But it was the basic who-won-it formula that gave the trial its unique character. This, which has survived the event’s several subsequent reworks, locale transplants, and shifts of organizational authority, took account of elapsed time for the course and observation. Thus the Scott was and is a race with a premium on non-stop traversal of indicated sections. When Bultaco rider Malcolm Rathmell won the Alfred A. Scott Memorial Trophy, he didn’t turn fastest time and wasn’t best on observation, but his average for both factors beat all rivals’. Prior to this Rathmell victory, Sammy Miller had won four Scotts in a row, a record in itself, and seven in all, another record, so Mr. Wonderful’s absence from the 1971 lists didn’t exactly desolate the trophy aspirants who did show.

The Scott Trials of all time, both in their original Wharfedale/Nidderdale/ Washbirn setting and later—post 1937in North Yorkshire, have had one thing in common: their savagely misanthropic terrain. The moorlands of Yorkshire, and the lowland water courses that enclose them, have a little of everything: tracts of peat bog that can engulf a bike up to its handlebars and its rider to his navel before he knows what he’s hit; gradients worthy of funiculars; landscapes that become ooze oceans in the rainy season (currently the trial comes off in October and Yorkshire at this time isn’t exactly arid); vertiginous paths clinging to the brinks of minor chasms; omnipresent rocks, or “geological fragmata” as the program once playfully put it, in super-abundance and infinitely ranging shapes and sizes— death to such projections as footpegs, brake and shift pedals; fords that are barely fordable, and not always that with just one pair of hands to reinforce horsepower....

For anyone who was going to write a biography of an English trial, the Scott would inevitably be, and was, its subject. The Greatest of all Trials, by the late Philip H. Smith, himself a one-time competitor, took the story up to 1938. Smith wrote it from material largely supplied by Harold Wood of Bradford, whose personal endeavors likely did more to make the Scott Trial the greatest than any other individual’s. Wood, now well into his 60s, still owns a 1912 Scott and runs it in Vintage events, and was a prominent Scott Trial rider in the mid-20s but switched to the organizer’s role when, in 1925, he worried that the affair was “getting too easy.” Well, maybe it was, or maybe the new upswing in the percentage of finishers merely reflected Horace’s law that “adversity is wont to reveal genius.” Either way, Wood, with his Yorkshireman’s relish for lines of most resistance, soon reversed the trend and restored riders’ mistrust in human nature.

In his Scott Trial riding days, Wood had early learned that all is not lost, ever, as long as there’s a gasp of breath left in your lungs and your engine is firing on at least one cylinder or hasn’t gone irrevocably beyond restoration to a firing state. In 1924 he retired, then restarted, not once but four times, twice after stopping to help hopelessly bogged down fellow riders extrude themselves from terra infirma and getting deep into debt to schedule in consequence, once when delays on his own account set him even further back, finally when the conviction dawned (wrongly) that the trial must have long since desisted and gone home. Eureka, it was still in business, yawningly, when he made it to the finish. Next morning he almost choked on his breakfast cereal on reading in his local paper that he’d won a veritable trophy, for second best performance on observation.

The Scott Trial story abounds in episodes that would have kept Horatio Alger supplied for half a lifetime with themes of noble endeavor overcoming stacked odds. In one of the wet years, following a week of almost nonstop rain locally, there was an authentic case of a rider suffering total immersion and narrowly escaping drowning in a swollen stream. There was just one point, as it seemed to him after giving the geography a preliminary casing, where he might, by backing up and taking a rush, attain sufficient flying speed for an aerial crossing of this hazard. He might have, at that, if his throttle wire hadn’t snapped at the moment of takeoff. According to an eyewitness, the flyer and his mount traveled 40 yards downstream, completely submerged, before resurfacing.

In 1930, the year a deluge forced the organizers to replan much of the course at the 11th hour as the only alternative to a complete DNF list, a Sunbeam rider was traversing a rickety plank bridge over a torrent called Holme Gill when the boards gave their last groan and collapsed under him. In, plop, up to his goggled eyeballs.

Conditions like these, and the generally forbidding character of the Scott Trial country, constituted a poison calling for strong antidotes. In addition to such standard practices as the elevation of exhaust outlets and carb intakes to around armpit level, armoring of crankcases against rocks with steel shields, waterproofing the high tension and gasworks departments with adhesive tape, Plasticene and shrouds of rubber sheeting, there was, author Philip Smith recalls, a subtle device whereby, “the magneto could be pressurized from the sidecar passenger’s air cushion, to keep water out of the sparks.” Sidecar outfits, surprising as it seems, enjoyed a considerable vogue in the early chapters of Scott Trial history. In 1925, a field of 117 starters included 22 sidehack jobs. One of these, a Scott rigged and ridden by a local specialist in the trial,

W. Bradley, featured dual gearboxes giving six ratios and doubled up on traction by taking the drive to the sidecar and back wheels both.

Post-WWI, in 1919, the Scott Engineering Company resumed its Scott Trial organizing role. Matters continued this way through 1925, but in ’26, in obedience to an ACU ordinance restricting the promotion of competitions to ACU sanctioned bodies, the Bradford and District Motor Club took over. A second abdication in 1950 was to give the job to another of the region’s long established clubs, Darlington, which still holds the reins today. It is a points rating event for the British trials championship and, in 1970 and ’71, decided the series in favor of Gordon Farley.

In 1919 the Scott firm withdrew its Scotts-only proviso, opening the door to all makes. This it could do, at that date, without undue risk of its products’ eclipse, for the legendary parallel Twin strokers still enjoyed a number of advantages over most of the competition. The Scott’s fully triangulated frame was almost impregnably strong; yet the machine as a whole was light, relative to most four-strokes of equivalent displacement, and therefore lent itself to muscle powered extrication from morasses. It had all chain transmission at a time when slip-happy belts were still quite common elsewhere. Its rocking pedal gearchange—a Scott exclusive—enabled the harassed rider to keep both hands on the bars in situations where a split second’s removal of just one hand could incure a bruise-inflicting of even bonebreaking fall.

Initially the rescinding of the ban on outsider makes had a sobering effect. In 1919, entries soared to 74 and, whisper it not in Wharfedale, a Triumph rider carried off the big prize. But Alfred Angus's disciples fought back dourly and, from 1920 through `23, notched four consecutive victories. It was in 1923 that A. A. Scott, designer/maker of one of all-time's most remarkable motorcycles, died. A bachelor with a passion for the rain-drenched solitudes of the Yorkshire moors, he caught pneumonia while exploring the region's subterranean caverns and never recov ered. It was not until 1927 and the ninth contest in the series that his pioneership of the Scott Trial was fitly acknowledged by the donation by the ACU's Yorkshire Center of the Alfred Scott Memorial Trophy as the event's premier award.

Not inappropriately, considering the rigors of the fray and the big fields it hhs usually attracted (236 entries, for instance, in 1960, and repeatedly in excess of 100 during the 20s), it’s a tradition that all finishers within a liberal time limit receive souvenir certificates. For many years there was also a special prize for the highest placed Scott rider, likewise one for best performance by a woman competitor.

On the grounds that a section that was wide enough for a sidecar outfit gave soloists more elbow room than was good for their souls, solos-only became the rule in 1928, the course being officially described as “69 miles long by nearly 6 in. wide.” Too, by the simple process of changing from a September to a December date, the Bradford and District sadists put nature even more spitefully to work. A third innovation in ’28 lumped the whole entry together-it previously had been divided into trade and amateur categories, with separate awards for each.

Befitting the Scott Trial’s pure race essence, it attracted, in the days before specialization took its present hold on motorcycle sport, a strong lacing of road racing talent. Prominent in this school were Vic Brittain, a Midlander

who in 1929 rocked the Yorkshire natives back on their heels by winning the very first time he competed, an unprecedented feat; George Dance, Sunbeam’s habitual TT record lapper; Stanley Woods, statistically the most successful TT and continental GP rider of the 20s and 30s; and Geoff Duke, whose Isle of Man exploits on Nortons and Güeras are emblazoned across TT history.

Stanley Woods once paid a memorable tribute to the Scott Trial, describing it as, “in my opinion the king of sports, with road racing a good second.” After prematurely finishing the rugged 1926 event in a peat bog at Sug Gill Moor, from which nothing and nobody could exhume his sucked down bike, he confessed, “I couldn’t move another yard for ten thousand pounds.” But “impossibüities recede as experience advances,” and five years later we find Stanley upholding old Ireland’s honor by outracing the whole Scott Trial field in 1931.

Another time, an exploratory divergence from the course around Applegarth Heights led Woods to and over the brink of an abyss. Landing in a bush at the bottom, he was eventually discovered and manhandled to firmer ground, where a broken leg was diagnosed and an ambulance summoned. Woods and other Irish invaders of the Scott Trial enjoyed a minor advantage insofar as at least one of the Republic’s major trials, the Hurst Cup, was run, like the Scott, on the time/observation formula.

Bruised and confused riders weren’t always amused by the facetious notices that used to be displayed at supposedly appropriate points around the Scott course, and George Dance, updandered by a placard inquiring “enjoy that?” rode flatout at it and pulped it underwheel.

The decline in the fortunes of Scott machines in the Scott Trial is illustrated by the fact that they won four out of the first five rounds (this of course included the 1914 opener which they couldn’t lose), three in the second five and one the third. This isolated success, by Yorkshireman Allan Jefferies, father of the 1971 Junior TT winner, made 1932 a year to be remembered, and grieved over by the make’s faithful followers, for the trial was never again won on a Scott.

Several factors contributed to the downfaU of the bike that gave the “Greatest of all Trials” its name: in the late 20s and early 30s, Scotts became progressively heavier, and this, under extreme conditions of moorland mayhem, lost them much of their old maneuverability. Concurrently, rival four-stroke Singles were improving fast ' in point of handling and making good use of the plonkability that afforded a deep bite into soft and oozy surfaces.

The two-cylinder stroker’s turbine-like power delivery, on the other hand, while enviable in a fast roadster, paid few dividends in a peat bog. The singlecylinder Scott introduced in 1930 (its water cooled two-stroke engine was effectively half of a 596cc Twin) came close to winning the 1929 trial but otherwise did nothing to revive the marque’s moorland glories of the past.

It was in 1929 that, for the first time, Scotts slipped to 2nd place (outnumbered by Sunbeams) in quantitative representation, but this still wasn’t too shameful considering there were no less than 28 makes in the act all told. That statistic alone underscores the glamor the event had acquired, and which in 1932 drew eight rival movie newsreel companies to the battle scene.

Just once, prior to the sidecar ban, a Morgan three-wheeler driver had the gall to enter, but made an early and ignominious exit. Braver still perhaps were Londoners Colin Harley and Jack Watson-Bourne, both big beefcake types, who rode lOOOcc Twin solos, AJW and Brough Superior respectively, in 1929. These bikes weighed around 450 lb. each. Sunbeams had an outstanding record of Scott Trial success, thanks in particular to Eddie Flintoff, a fractureproof Yorkshire men, who was the first non-Scott rider to notch two outright wins in a row. A man of initiative, he liked the way “the flags marked the best path over the moore from point to point, but left room for a little pioneering-which sometimes paid off but often did not.” A veteran of the mid-20s era, Flintoff refused to let anno domini sever him entirely from the “king of sports” and was still to be seen struggling around the course, noncombatantly, as late as 1959, on a 1928 ’Beam.

The typical Scott Trial rider was and is dumb, but not for the reason postulated by Alfred Angus Scott. His dumbness has something in common with a Kamikaze pilot’s—he isn’t compelled to martyr himself but, just for the hell of it, he does. Every year since 1914, at the wound-licking parties that make the night hideous at the headquarters tavern the evening of D-Day, never-again vows have been registered by the score. Nevertheless, the Scott bug, when it bites you, doesn’t desist easy. Competitors who first tried conclusions with Cat Crag, Cockbur Wood, Loftshaw Gill, Low Moor and Jefsfynde in their late teens or early 20s, were still taking punishment from Hell Holes, Underbanks, Nut Brown, Shawgill and Clapgate Gorge a decade and a half later. That this was a street that didn’t have a sunny side was no deterrent to them.

The long-term allegiance that the trial and its affairs inspires was emphasized when no less than 16 out of 26 past winners attended the Golden Jubilee dinner held in Yorkshire in 1964.

These included Scotchman Clarrie Wood, who had competed in 1914 and won the 1920 and ’21 trials. In a speech, Jeff Smith, motocross world champion of ’64, echoed the general sentiments of his fellow dumbells with the comment that, “once the Scott Trial bites into your body you can’t leave it alone.” Motor Cycle’s report of the festivities recalled that, “through the years it has remained virtually unchanged in concept. No pandering to current ideas of short, highly specialized courses that are covered in a leisurely couple of years. We could do with fewer of them and more that offer a challenge to the rider’s courage and sense of adventure....”

In hierarchic terms, too, the Scott Trial has set an example that could well be copied elsewhere. Eligibility for presidencies is measured by a man’s riding record in “The Greatest,” not by the blueness of his blood, his standing in regional politics or his potential as a donor of expensive trophies. Former president Tom Ellis, for instance, who has also been president of the ACU’s Yorkshire Center, contested about a dozen Scott Trials and finished in most of them. A man like that talks the same language as the breed of dumb Englishmen, Scotch and Irishmen he’s liable to meet out there on the moors.

Organizing the Scott, and in particular its course plotting, often calls for as much “courage and sense of adventure” as it demands of competitors themselves. This was especially true perhaps in the 20s and 30s, when one man, Harold Wood, was taking about six men’s share of the chore on his shoulders. It required not only an encyclopedic knowledge of the available tracts, a boundless capacity for furlong by furlong exploration and, in crises, the resourcefulness of the Swiss Family Robinson, but also a well developed bent for smoothtalk diplomacy.

The latter was indispensible because, if the trial’s essential character as a race was to be preserved, public road mileage, subject to legal speed limits, had to be kept to the absolute minimum. And anything that wasn’t public road, it followed, was privately owned land, property of local farmers. Between 30 and 40 of these squirlings would need to be canvassed for permission to invade in a single year, and their OKs, where granted, obtained in writing. This wooing bred an unwieldy correspondence and one Scott Trial could involve the principal organizer in the writing of over a thousand letters.

Rebuffs from farmers were, in fact, relatively few, and as the Bradford club acknowledged in 1931: “Most of these gentlemen, although in no way interested in motorcycling, prove themselves to be true sportsmen. Stock is moved from fields, gates closed after the event, (Continued on page 122) Continued from page 109 and even fences removed to meet our requirements. All that is asked in return is that spectators show the same consideration and remember that they are guests on private property.” It’s on. record that one landowner, after promising the Scott cohorts, some weeks in advance, the freedom of his acres, forgot his undertaking and arranged a private shoot over the same ground on the same day. When told of the oversight he cancelled his shoot and let the trial roll.

Route marking, by flags on stakes, was a chore necessarily deferred until the eve of the trial, and carried out by two sidecar outfit crews of three men apiece. This system, one year in the small 20s, had an upshot at which the mind boggled. One of the crews was captained by an official with limited knowledge of his section of the countryside. Delays resulting from his relative inexperience set his progress back until he ran out of daylight and thereafter had to grope his way through a largely unfamiliar wilderness by the glimmer of a sickly headlamp beam. “This,” it was written, “suddenly fell upon a vast expanse of black nothing, and the party found itself on the brink of a precipice. No trace of the supposed course could be found, so there was no choice but to retrace the marking and struggle home. Thus, at midnight on the eve of the trial, the organizers learned that within 15 miles of the start the existing marking would conduct competitors to the edge of a high cliff and leave them to their own choice of ways. This state of affairs was indeed remedied only 10 minutes before number one came along.”

Riders, as distinct from officials, have twice done a babes in the wood act and perforcedly spent a whole night out on the wind and rain lashed course, under the invisible Yorkshire stars. The first time, during the Darlington club’s reign, the word went around, “rider

missing on course,” at the height of the beer gulping junket that traditionally enlivens the prizegiving ceremony a few hours after the finish. A rescue party, around 30 strong, thereupon “drunkenly donned wet Barbour suits, grabbed torches and rode forth to the search area. We then walked the moors in groups for several hours but all that we located were pheasant.” Finally the quest was called off and the castaway came to light next morning, huddled down in an isolated barn.

The other rider involved in this kind of misadventure didn’t even find himself a barn for a boudoir. Following the correct moorland survival technique, he decided his best chance of rescue lay in staying on the course, which only afforded him a large specimen of geological fragmata for protection against the climate. Totally exhausted, he tried flashing his cigarette lighter at intervals, but nobody saw these signals because there wasn’t anybody within miles, except perchance a spectral Alfréd Angus Scott. For their longitude, few places on the face of the earth are more frigid in winter than the Yorkshire moors, and two-time winner Allan Jefferies recalls an attack of cold induced cramp during a Scott Trial that paralyzed him until a cop skilled in massage showed up and pummeled some feeling back into his limbs.

It’s doubtful whether any other British trial, or motorcycle event of any kind, has a record of inter-rider chivalry to compare with the Scott’s. Even today, when keeping going can put important money in the bank for a man, the standard of Samaritanism is high; but back in the youth of such legendary Scottisti as Clarrie Wood, Billy Moore, Tommy Hatch and Eddie Flintoff, it was a tacit law that you went to the aid of any and every distressed rival you sighted. In the long run, of course, such acts of abnegation likely supplied their own reward, for next time it would be your turn to break a chain, cop a flat or glug down to your license plates in a peat bog, and the other fellow’s turn to render you assistance.

Harold Wood’s explorations in the line of route planning duty yielded finds of long lost hardware that would have made the nucleus of a Scott Trial museum...a complete, half buried exhaust system, horns, license plates, brake pedals, brackets, toolboxes, tire levers and “a pathetic souvenir in the form of a piece of cloth with a coat button still attached.” Following the inclusion of a stretch of disused railway track at Appletreewick around 1929/ 30—its traversal was compulsory—a diligent searcher might have turned up a few dentures, too. At least two Scott Trial routes followed sections of “supposed Roman roads” in the Denton Moor neighborhood, and although these disclosed no relics identifiable with the First Century B.C. it’s probable that the ruts cut by the spinning back wheels of Scotts, Sunbeams and Triumphs were almost the first imprinted there since the Latin conquerors’ chariots passed that way.

For the route planners, the problem was always basically the same—shaping conditions that on the one hand would crowd without finally overstepping the limits of strength and reliability for bikes, and on the other, test human endurance to the utmost without actually bringing the entire caper to a premature halt. As Philip Smith put it: “To wreck machines on brutally rocky surfaces, or exhaust nearly all the riders in deep morasses, would defeat the object of the trial; yet, recognized as it is as the supreme test of man and motorcycle, the event must increase in severity year by year.” This, indeed, it did, and in the process evolved a breed of roughriders of the caliber of BSA star Bill Nicholson, for example, who won outright five times in six post-WW2 years, ending 1951, thereby foreshadowing the even more stunning record of Sammy Miller in the era that opened in the late 50s.

For almost 60 years the mystery of the survival and continuing success of the Scott Trial has baffled penetrating minds. It started, Motor Cycle thinks, “as an outlet for the Yorkshireman’s peculiar sense of humor,” also of course to confirm A.A. Scott’s credo that dumb Englishmen don’t know left from right from straight on. A possible explanation for its longevity is offered by former Scott trialsman and Darlington club president Tom Ellis: “Like knocking your head against a brick wall, it’s nice when you stop.” Either way, it would reassure old Alfred Angus that one established expert lost his first class award in 1971 by inadvertently following a yesteryear’s trail, and that winner Malcolm Rathmell drowned out his engine in a splash, snapped off his brake pedal, punctured a tire and had to ride six miles on the rim, and locked up his back wheel on a twisted chain tensioner. Hail to the Scott Trial.