Those Rapid, Rugged, Racing Rudges

SIMON READ

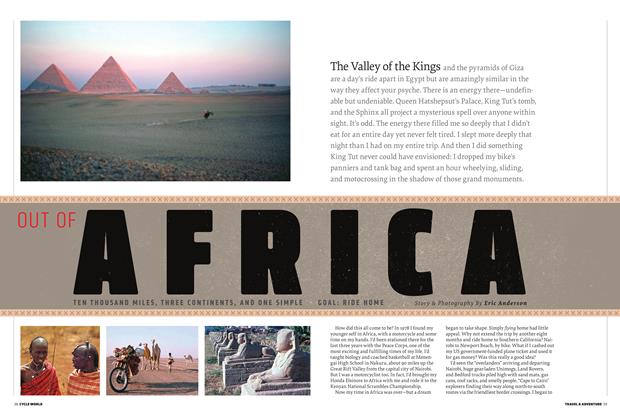

RUDGE, WHOSE place among the motorcycle grandes marques was never disputed in its 30-year lifespan (1910 through 1939), was forever springing surprises, setting the laws of the Swedes and the Prussians at naught. It did so, technically, with its espousal of four valves per cylinder in 1924, just when the only other English exponent of this arrangement, Triumph, with its quadspout Ricardo model, was ditching it. Then, six years later, Rudge fathered a variation on the multi-valve theme —four radial ohv, an adaptation of a long since discarded aircraft recipe— that leapt overnight to sensational success with a 1-2-3 score in the Junior TT, straight off the drawing board. In the small ’30s, less dramatically but with a long-term significance that time was to prove, the make blew its own trumpet in a double sense by inventing the exhaust megaphone.

Much earlier, back before all-chain drives had become standard in Europe, as they were in the U.S., Rudge had anyway made the best of the horrendous belt transmission by endowing it with up to 23 gearing steps: this gizmo, which gave the history-making Rudge Multi its signature feature, was largely instrumental in giving Rudge its first Tourist Trophy, in the 1914 Senior race.

It takes original men at all levels— directors, designers, riders, el al-to create original and successful motorcycles, and Rudge-Whitworth Ltd., certainly was not lacking. Big, bluff, autocratic John V. Puch, for many years the executive head of Rudge, exercised almost dictatorial power over the firm’s affairs and made good use of his immunity from committee-type interference and cajolery.

George Hack, a physically unimposing man with a piping voice, not much chin, eyeglasses and a thin, pale face, nevertheless had an imposing will and gave a basic continuity to the company’s engineering philosophy by holding down his job, in charge of design and development, throughout its four-valve chapter. (He was later to become a technical luminary of the Bristol Aeroplane Company, from which he retired some years back. At around age 70, Hack remarried and started raising a second family.)

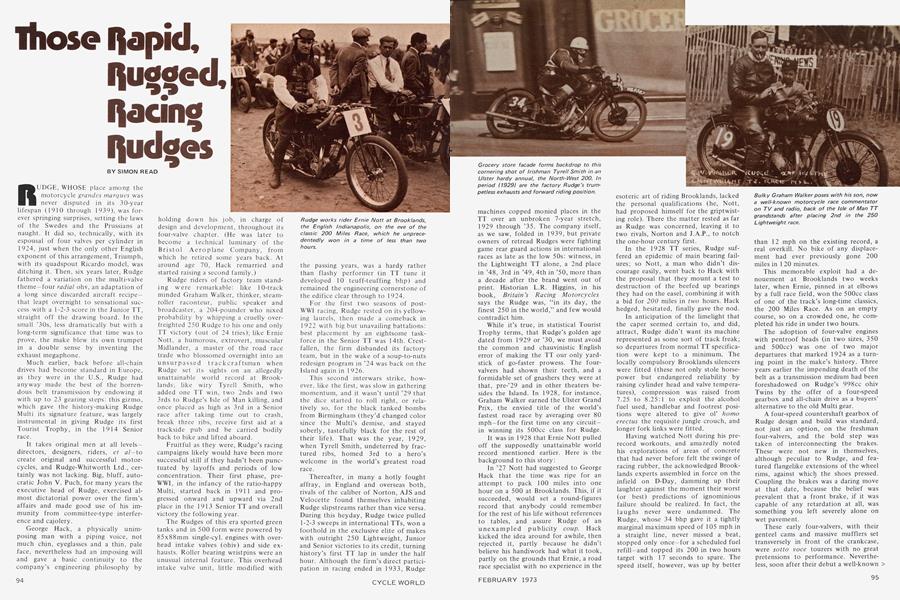

Rudge riders of factory team standing were remarkable: like 10-track minded Graham Walker, thinker, steamroller raconteur, public speaker and broadcaster, a 204-pounder who nixed probability by whipping a cruelly overfreighted 250 Rudge to his one and only TT victory (out of 24 tries); like Ernie Nott, a humorous, extrovert, muscular Midlander, a master of the road race trade who blossomed overnight into an unsurpassed track craftsman when Rudge set its sights on an allegedly unattainable world record at Brooklands; like wiry Tyrell Smith, who added one TT win, two 2nds and two 3rds to Rudge’s Isle of Man killing, and once placed as high as 3rd in a Senior race after taking time out to crash, break three ribs, receive first aid at a trackside pub and be carried bodily back to bike and lifted aboard.

Fruitful as they were, Rudge’s racing campaigns likely would have been more successful still if they hadn’t been punctuated by layoffs and periods of low concentration. Their first phase, preWWI, in the infancy of the ratio-happy Multi, started back in 1911 and progressed onward and upward via 2nd place in the 1913 Senior TT and overall victory the following year.

The Rudges of this era sported green tanks and in 500 form were powered by 85x88mm single-cyl. engines with overhead intake valves (ohiv) and side exhausts. Roller bearing wristpins were an unusual internal feature. This overhead intake valve unit, little modified with the passing years, was a hardy rather than flashy performer (in TT tune it developed 10 teuff-teuffing bhp) and remained the engineering cornerstone of the edifice clear through to 1924.

For the first two seasons of postWWI racing, Rudge rested on its yellowing laurels, then made a comeback in 1922 with big but unavailing battalions: best placement by an eightsome taskforce in the Senior TT was 14th. Crestfallen, the firm disbanded its factory team, but in the wake of a soup-to-nuts redesign program in ’24 was back on the Island again in 1 926.

This second interwars strike, however, like the first, was slow in gathering momentum, and it wasn’t until ’29 that the dice started to roll right, or relatively so, for the black tanked bombs from Birmingham (they’d changed color since the Multi’s demise, and stayed soberly, tastefully black for the rest of their life). That was the year, 1929, when Tyrell Smith, undeterred by fractured ribs, homed 3rd to a hero’s welcome in the world’s greatest road race.

Thereafter, in many a hotly fought affray, in England and overseas both, rivals of the caliber of Norton, AJS and Velocette found themselves inhabiting Rudge slipstreams rather than vice versa. During this heyday, Rudge twice pulled 1-2-3 sweeps in international TTs, won a foothold in the exclusive elite of makes with outright 250 Lightweight, Junior and Senior victories to its credit, turning history’s first TT lap in under the half hour. Although the firm’s direct participation in racing ended in 1933, Rudge machines copped monied places in the TT over an unbroken 7-year stretch, 1929 through ’35. The company itself, as we saw, folded in 1939, but private owners of retread Rudges were fighting game rear guard actions in international races as late as the low 50s: witness, in the Lightweight TT alone, a 2nd place in ’48, 3rd in ’49, 4th in ’50, more than a decade after the brand went out of print. Historian L.R. Higgins, in his book, Britain’s Racing Motorcycles says the Rudge was, “in its day, the finest 250 in the world,” and few would contradict him.

While it’s true, in statistical Tourist Trophy terms, that Rudge’s golden age dated from 1929 or ’30, we must avoid the common and chauvinistic English error of making the TT our only yardstick of go-faster prowess. The fourvalvers had shown their teeth, and a formidable set of gnashers they were at that, pre-’29 and in other theaters besides the Island. In 1928, for instance, Graham Walker earned the Ulster Grand Prix, the envied title of the world’s fastest road race by averaging over 80 mph—for the first time on any circuitin winning its 500cc class for Rudge.

It was in 1928 that Ernie Nott pulled off the supposedly unattainable world record mentioned earlier. Here is the background to this story:

In ’27 Nott had suggested to George Hack that the time was ripe for an attempt to pack 100 miles into one hour on a 500 at Brooklands. This, if it succeeded, would set a round-figures record that anybody could remember for the rest of his life without references to tables, and assure Rudge of an unexampled publicity coup. Hack kicked the idea around for awhile, then rejected it, partly because he didn’t believe his handiwork had what it took, partly on the grounds that Ernie, a road race specialist with no experience in the esoteric art of riding Brooklands, lacked the personal qualifications (he, Nott, had proposed himself for the griptwisting role). There the matter rested as far as Rudge was concerned, leaving it to two rivals, Norton and J.A.P., to notch the one-hour century first.

In the 1928 TT series, Rudge suffered an epidemic of main bearing failures; so Nott, a man who didn’t discourage easily, went back to Hack with the proposal that they mount a test to destruction of the beefed up bearings they had on the easel, combining it with a bid for 200 miles in two hours. Hack hedged, hesitated, finally gave the nod.

In anticipation of the limelight that the caper seemed certain to, and did, attract, Rudge didn’t want its machine represented as some sort of track freak; so departures from normal TT specification were kept to a minimum. The locally compulsory Brooklands silencers were fitted (these not only stole horsepower but endangered reliability by raising cylinder head and valve temperatures), compression was raised from 7.25 to 8.25:1 to exploit the alcohol fuel used, handlebar and footrest positions were altered to give ol’ homo erectus the requisite jungle crouch, and longer fork links were fitted.

Having watched Nott during his prerecord workouts, and amazedly noted his explorations of areas of concrete that had never before felt the swinge of racing rubber, the acknowledged Brooklands experts assembled in force on the infield on D-Day, damming up their laughter against the moment their worst (or best) predictions of ignominious failure should be realized. In fact, the laughs never were undammed. The Rudge, whose 34 bhp gave it a tightly marginal maximum speed of 105 mph in a straight line, never missed a beat, stopped only once—for a scheduled fuel refill-and topped its 200 in two hours target with 17 seconds to spare. The speed itself, however, was up by better than 12 mph on the existing record, a real overkill. No bike of any displacement had ever previously gone 200 miles in 1 20 minutes.

This memorable exploit had a denouement at Brooklands two weeks later, when Ernie, pinned in at elbows by a full race field, won the 500cc class of one of the track’s long-time classics, the 200 Miles Race. As on an empty course, so on a crowded one, he completed his ride in under two hours.

The adoption of four-valve engines with pentroof heads (in two sizes, 350 and 500cc) was one of two major departures that marked 1924 as a turning point in the make’s history. Three years earlier the impending death of the belt as a transmission medium had been foreshadowed on Rudge’s 998cc ohiv Twins by the offer of a four-speed gearbox and all-chain drive as a buyers’ alternative to the old Multi gear.

A four-speed countershaft gearbox of Rudge design and build was standard, not just an option, on the freshman four-valvers, and the bold step was taken of interconnecting the brakes. These were not new in themselves, although peculiar to Rudge, and featured flangelike extensions of the wheel rims, against which the shoes pressed. Coupling the brakes was a daring move at that date, because the belief was prevalent that a front brake, if it was capable of any retardation at all, was something you left severely alone on wet pavement.

These early four-valvers, with their genteel cams and massive mufflers set transversely in front of the crankcase, were sotto voce tourers with no great pretensions to performance. Nevertheless, soon after their debut a well-known trackster of the day, Col. R.N. Stewart, with his wife as co-rider, set a respectable endurance record by averaging 54.21 mph for 24 hours on a 350 that was stock, apart from its oversize tank.

It was in 1926-27 that the rapid, rugged Rudges first assumed the shape and character that for years to come would represent the vintage ideal for the make’s innumerable idolaters worldwide. These four-valve Singles (the 350 size was dropped in ’26), had a compactness and a sort of rotundity that it was hard to resist. They were, for their displacement, small bikes, and their engines were small too, kept low on stature by an economy of head finning that never seemed to provoke overheating troubles. Rudges had none of the ranginess of the contemporary Nortons, or the excessive height and length of steering head that marred the looks of the saddle-tank Sunbeams that were to debut in 1928. Rudge’s own saddle tank, a pleasantly bulbous design that would survive with only minor variations throughout the four-valve chapter, was a staple ingredient, aesthetically, in the new deal embarked upon in 1926-27.

In the 1927 TT Rudge fielded experimental machines that were conspicuous for their switch from rim type to internal expanding brakes of unprecedentedly large diameter and width. These, too, were interconnected and soon became standard wear. Other developments, both destined for street bikes and racers of successive crops, included the enlargement of all ports and the splaying of the exhaust pair (they’d previously been parallel); and the paralleling of the closely neighbored pushrods (they’d previously been splayed).

There never seemed to be much reason or rhyme about Rudge’s product planning, though this by no means made the firm unique in the British motorcycle industry of 35 or 40 years ago. The 350 four-valver for instance, had been born, as we saw, in ’24, then died an interim death in ’26, only to rise again in ’29. This apparently haphazard resuscitation presaged—though only the psychic could forsee it—the advent in the Isle of Man the following year of a bike, or more exactly an engine, that would scoop all the marbles the very first time it came to the line: the radial-valve 350, ridden into 1st, 2nd and 3rd places by Tyrell Smith, Ernie Nott and Graham Walker, setting race and lap records for good measure. A technical sidelight on this feat was that Rudge, well after Velocette, AJS and Norton had gone overboard for overhead camshafts, astonishingly made pushrods one of the staples of its new engine.

One of Hack’s main worries, once he’d embarked on the quest of a formula for operating four valves that stuck out of the head at angles recalling the machine guns in WWII airplane ball turrets, was keeping reciprocating weight down to levels that wouldn’t limit revs too much. His solution was to mate each pushrod to three rockers, one disposed north/south, the other two east/west. When the cam hoisted one end of rocker one, its opposite end depressed one valve and simultaneously actuated rocker two, which carried the motion across the head to the second of the two relevant valves. There was no swiping contact anywhere between rocker face and valve stem, only a true rolling action—an important asset.

The 350s to which the radial upperworks were first applied—corresponding 250s and 500s were to follow—measured 70x90mm and, like the traditional pentroofers, had their spark plugs central in the head. Here, owing to the disposition of the valves, they had ample iron around them. Not only the top ends of these 350s but most of the mechanical elements at sub-head level too were new and beefier than the ’29s, in expectation of a gain in horsepower that was certainly realized. The centrally placed plug, incidentally, surrounded by all that ferrous undergrowth, was damnably inaccessible; after road testing the radial 250 on which Walker won the 1931 Lightweight TT (followed in 2nd spot by Tyrell Smith on a similar bike), a reporter on one of the English shoptalk magazines confessed that it took him 40 wrench applications and lift-offs to disinter the plug.

Curiously enough, the 500 version of the radial Rudge was never raced, though it became standard on the hot Ulster roadster in 1931, which afterward acquired a semi-radial head. This, obviously less complicated, expensive and noisy than the fullhouse arrangement, had a combustion chamber that somehow contrived to merge hemi and pentroof contours. As a 250, the full radial came close to repeating the 350’s 1-2-3 cleanup of 1930 by placing 1-2 in the ’31 Lightweight. While leading by four minutes, Nott suffered a slacked off tappet late on the last lap, finally finishing 4th with Walker and Tyrell Smith up in the two top places. “I didn’t win—I finished first,” the magnanimous Graham declared afterward.

All the radial Rudges that were ever raced or sold had single carbs, though Hack experimented with duals at one period. Another and even more intriguing backroom exercise by Rudge-Whitworth spawned a 250 V-Twin with all-radial valves. This, without benefit of any sort of development or detailed puning, equalled the corresponding Single’s performance; but, hatched as it was toward the end of the firm’s racing career, when wholesale economics were the watchword, it was prematurely shelved. The only other British make that espoused the radial-valve engine was Excelsior, which raced two versions in the low ’30s, one a pushroder, the other with ohc. Excelsior never admitted it but the latter’s rocker gear was pure Rudge, which you could prove by taking the top end apart to disclose a tiny and obscure plate bearing the relevant Rudge patent number. It was on the radial Rudges, in 1931, that megaphoned exhausts emitted their first earnumbing bellow.

The established Rudge works team men, Walker, Nott and Smith, were not only fine riders but also sportsmen in the best traditions of their chivalrous day. It was directly on account of this that an outsider was given an opportunity that he exploited to win the only Senior TT ever dominated from start to finish by a Rudge. In 1930 the factory had prepped a spare 500, and a private sponsor had filed a Senior entry on the off-chance that a worthy rider would become available at the last minute. The meteoric Walter Handley, a freelancer, became available...so it was left up to Walker, Nott and Smith to decide whether the fourth factory bike should be put at Wal’s disposal. They voted aye, and Wal won practically as he liked, turning in history’s first Manx lap in under the half hour in spite of heavy rain.

When its financial straits became parlous along toward the end of 1932, Rudge-Whitworth Ltd. reluctantly decided it’d have to quit racing and devote the money saved to more mundane purposes. Faced with this crisis, Graham Walker, who was a senior employee, called his fellow team riders into barroom conclave and formed the famous Rudge Syndicate, organized independent of R.W. but having the use of its existing race bikes. The Rudge Syndicate campaigned vigorously for two years, 1933 and ’34, repaying Rudge for its generous encouragement of and cooperation in the venture by pulling off yet another Tourist Trophy, in the 1934 Lightweight.

The rider in this case was another freelancer, former firebrand Jimmy Simpson, now a somewhat tamed veteran, who knew this was to be the last of his 26 TTs and was, he later confessed, chiefly anxious to make sure he didn’t wind up in a Manx morgue. Convinced, as this wet and foggy race wore on and his discomforts grew, that daring-do stuff was no longer for him, he tried to talk the Syndicate’s pit manager into letting him quit. Refused this request, he pressed on and won instead. The Island gremlins owed Jim this one, for although he’d turned more TT fastest laps and records in his time than he could remember, he’d never actually pulled a win since his introduction to the series in 1922.

At the end of ’34 the Syndicate broke up, though Tyrell Smith continued to race the pick of the stable’s 250 Rudges. These loner efforts copped him class wins in the Belgian and German GPs and his second 2nd on the Island. Graham Walker traded amateur for pro status as a journalist and became editor of Motor Cycling.

Meanwhile, on the production front Rudge had been successfully challenging such entrenched makers of proprietary engines as J.A.P. and Blackburne, at a time when well over half of Britain’s motorcycle manufacturers lacked the resources to design and build their own powerplants and looked to specialist supply sources. Solid under the name of Python in assorted sizes, mostly semi-radial 500s, these units did a brisk business in England and on the continent. There was even a wristwatchlike 175 with fully radial valves that a French, an Italian and a German maker took up.

This Python trade compensated Rudge for the loss of its earlier British monopoly, founded on the pentroof and semi-radial 500s, in the dirt track racing field, which had started around 1930-31, when Singles demonstrated their clear superiority over the too smooth Douglas Twins. It ended, just as suddenly and decisively, about two years later, when the lighter, easier to maintain and more powerful J.A.P. Singles beat hell out of the Rudge, just as Rudge had out of Douglas.

Alas for sentiment, which was forever rife, and still is, among the worldwide host of four-valve Rudge worshippers, Rudge Whitworth Ltd., in its later years, rethought its valve multiples philosophy and concluded that at least as far as the 250 size was concerned, two big poppets could do a better job than four little ones. The upshot was a bi-valve pushrodder with a normal hemi head, on one example of which, late in ’3 5, Ernie Nott and Tyrell Smith teamed for world record attempts at Brooklands. Elsewhere and in other hands, as C.E. Allen says, “the two-valve 250 ended up going quicker than the four-valve.” A mite deflatingly, he adds: “It’s doubtful whether four valves gave them any advantage.”

Ah well, it’s food for thought.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue