BSA 650 LIGHTNING

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

A Combination Of Good Basic Design, Refinement Thereof, Smart Styling In A Traditional Vein, And Inattention To Certain Important Details.

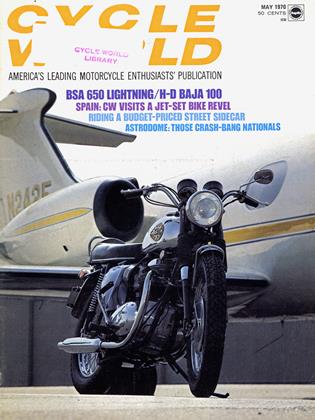

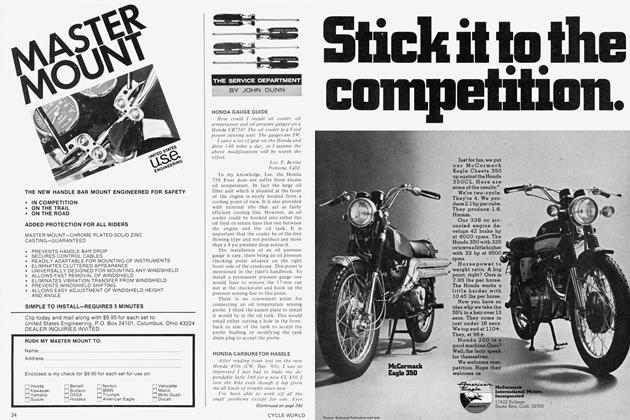

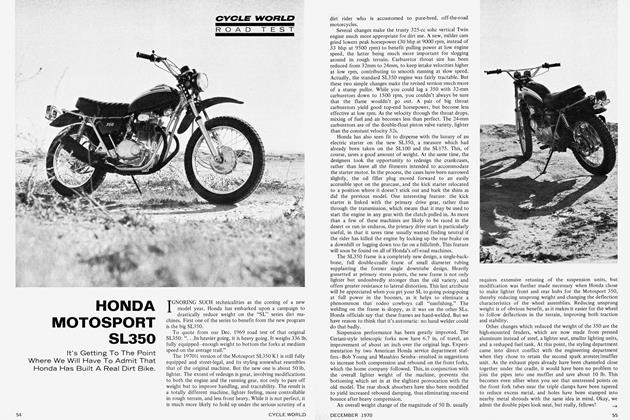

CAN THE OWNER OF a BSA 650 Twin find happiness in this superbike age? Yes, he can, if our visit to Orange County airport for a shooting session is fair indication. The way we figured it, the BSA would pose very nicely against a World War II fighter trainer we had seen there. They kind of went together, that Lightning and that T6. The T6, of course, has long been retired, but the 650 BSA, which is mechanically reminiscent of the same era, is still going strong in its updated form.

As we clicked away, a chap from Mission Beechcraft drove up in a truck. “Boy, I think that’s going to be my next bike. BSA is it, as far as I’m concerned. Hey, would you like to pose it next to a Gates Learjet?” “Is there one out there?” “No, but we’ll pull it out of the garage for you.”

Our ace cameraman—grumpy in the warm sun—opined that the T6 trainer was more appropriate, but if the guy was so stoked on the BSA Twin that he’d pull a one-million-dollar airplane out of the hangar for us, then maybe we should start thinking in Learjet terms. We didn’t quite believe him, until he introduced us to Capt. Don Chiovari, who did indeed pull out that fantastic twin-jet hotrod.

And it was all because of a BSA. Not the hottest thing in the BSA line. Not a superbike. But an object of reverence to this one man, and many others.

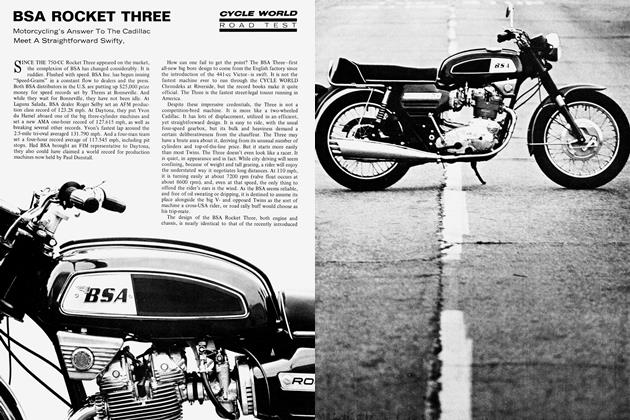

The new Lightning does indeed have a certain appeal about it. The 1970 styling has restored somewhat the classic appeal of British Twins of previous years, with the chromed tank sides, etc. It’s immutably the same, forever British. But somehow, certain improvements have been made, which no doubt tweak a few conservative Birmingham consciences. Howsoever subtle such changes might be, progress must prevail. For example, the cast iron cylinder barrel has a thicker base for 1970 and is secured to the vertically split crankcases by larger studs. Previous models used 5/16-in. diameter studs to hold things together, but now BSA has lurched into the present with 3/8-in, diameter studs. Apparently, the smaller fasteners had a tendency to flex under heat and stress, causing the studs to work free and pull loose from the cases. With such added beef the malaise should be no more.

Also the clutch actuating mechanism has been updated. The lever-and-rod linkage has been forsaken for a smoother ball-and-ramp type of assembly that offers greater mechanical advantage and less grabbiness or bind. It is much the same approach that BSA’s corporate cousin, Triumph, has used for the past few years.

The 654-cc vertical Twin has been around since 1962 when BSA adopted the unit engine/transmission configuration. The heart of the powerplant is a one-piece crankshaft supported by a steel-backed bronze bushing on the right side, while a caged roller bearing on the left absorbs primary drive loads.

Midway between crankthrows there is a large full circle flywheel attached to the crankshaft by three heat treated bolts while additional reciprocating balance is provided by intergral counterweights located outboard of the connecting rod journals. Forged aluminum connecting rods, pressure cast alloy pistons and 0.75-in. diameter full floating wrist pins complete the crank assembly. Now if these bits and pieces impress you as strong components, you’re right, for the typical 650 BSA competing on the AMA National circuit develops 57-60 bhp at 8000 rpm; as the man said, “That’s a lotta’ beans.”

With the exception of minor changes throughout the years to fork angle, engine mounts and such, the BSA frame has preserved the spirit of its 1954 beginnings. Made of steel tubing welded into a double cradle configuration, the unit is supremely conventional yet very strong.

For the 1970 models, however, there has been one substantial modification to the frame. The swinging arm now pivots on bronze bushings rather than the steel sleeved rubber bushings of yore. In this way handling is improved by eliminating any incipient flex of the older design.

The front fork and wheel are the same as those used on the 1970 Triumph model line, and this growing commonality of BSA and Triumph parts should make parts prices a little easier on the consumer along with the convenience of increased availability.

We rate the double leading shoe front brake as very good—both extremely sensitive and progressive. There was no trace of sponginess or shudder, traits prominent on the last Lightning we tested (CW, Feb. ’68). The rear brake operates smoothly with no grab.

In this age of superbikes the easygoing BSA makes no pretenses. It is a sumptious, torquey machine suited to a wide open highway where it can stretch its legs. A hefty machine, it is not quite the ticket for playing racer on country roads. To appreciate the Lightning, you must be in an element where you can put its 37 lb ./ft. of torque to use, and where you can make its weight work for you, smoothing out bumps and jolts. And in this context the BSA comes into its own. Its smooth, quiet gearbox, good muffling and excellent power band all contribute to fatigue free riding for hours on end.

But there were some flaws in its pleasant touring character. Most annoying is the undue amount of noise caused the chain rattling against its closely mounted guard. To the unsuspecting rider it would seem that the chain was perilously loose and about to leave the sprocket any time. Fortunately though, this shortcoming can be remedied with a pair of pliers to bend the offending portion of the guard away from the chain.

Another gripe is the imprecise steering response in the front end. Midway through a turn at moderate speeds an unnerving wallow is perceptible through the handlebar. This phenomenon is the result the oversize 3.50-19 Dunlop K70 tire on the front wheel. Up until this year BSA had shod their heavyweight bikes with 3.25-19 rubber yielding excellent results; steering was precise and easy. However, it seems that the American market demands big weenies for their street machines, mistakenly assuming that if a little footprint on the pavement is good, a bunch more is better. So, in complying with demand, the bikes now come with 3.50s on the front. Well, unfortunately, the big rubber doesn’t always work out and in this instance the tire’s surface tends to get squirmy in a curve. Our advice: request the 3.25-19 K70; there’s world of difference.

Bugaboo number three can be intolerable on a touring machine: vibration. At around 4500 rpm (60-65 mph) a vexing vibration begins. At this stage it’s not too bad, but as revs climb to about 5000 rpm it becomes quite annoying, much too distracting for long distance rides. We suspect the fault lies in loose engine mounts, a malady cured easily, but bothersome, nonetheless.

In summation, we were both pleased and disappointed by the BSA Lightning. We were tantalized by its basically good design features and styling, but frustrated by poor execution and inattention to certain details. Understandably, on machines of less character such faults would not have such a detrimental effect. However, with a machine of the Lightning’s superb potential they strike us more as cardinal sins. (51

BSA 650 LIGHTNING

$1430