HARLEY-DAVIDSON SPRINT H

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

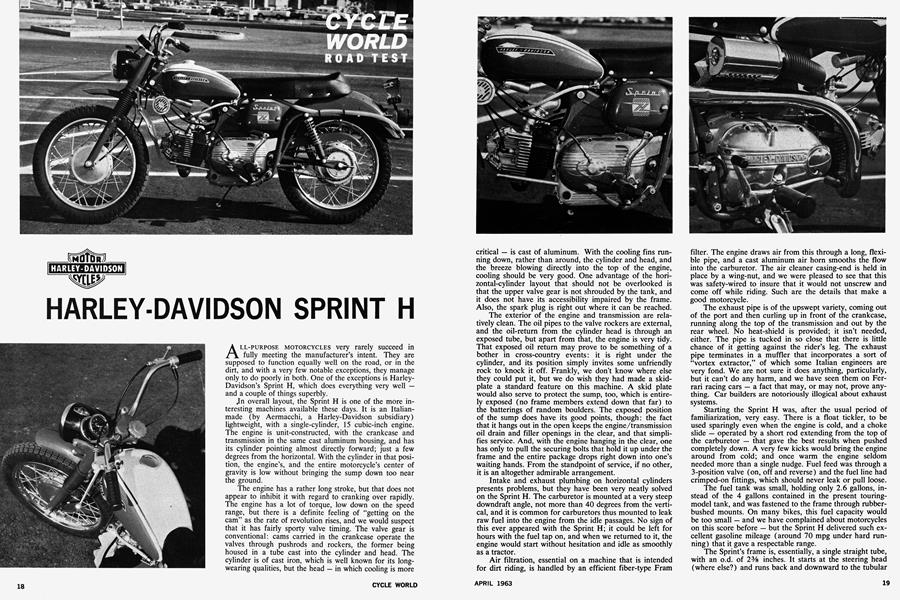

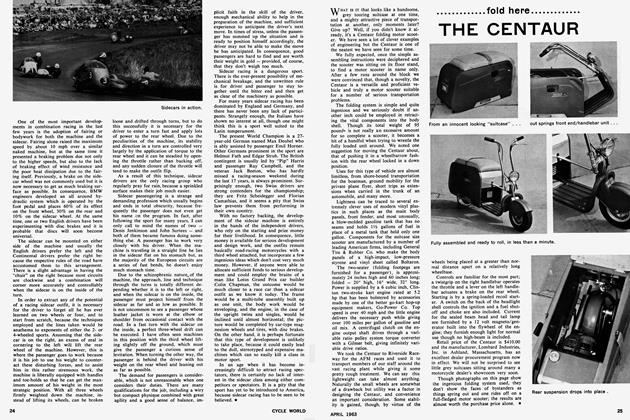

ALL-PURPOSE MOTORCYCLES very rarely succeed in fully meeting the manufacturer’s intent. They are supposed to function equally well on the road, or in the dirt, and with a very few notable exceptions, they manage only to do poorly in both. One of the exceptions is HarleyDavidson’s Sprint H, which does everything very well — and a couple of things superbly.

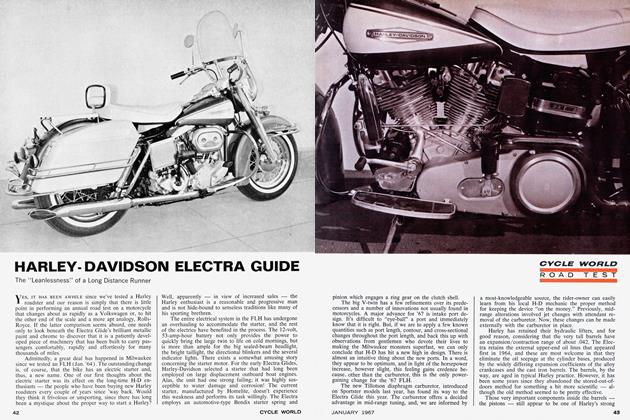

In overall layout, the Sprint H is one of the more interesting machines available these days. It is an Italianmade (by Aermacchi, a Harley-Davidson subsidiary) lightweight, with a single-cylinder, 15 cubic-inch engine. The engine is unit-constructed, with the crankcase and transmission in the same cast aluminum housing, and has its cylinder pointing almost directly forward; just a few degrees from the horizontal. With the cylinder in that position, the engine’s, and the entire motorcycle’s center of gravity is low without bringing the sump down too near the ground.

The engine has a rather long stroke, but that does not appear to inhibit it with regard to cranking over rapidly. The engine has a lot of torque, low down on the speed range, but there is a definite feeling of “getting on the cam” as the rate of revolution rises, and we would suspect that it has fairly sporty valve timing. The valve gear is conventional: cams carried in the crankcase operate the valves through pushrods and rockers, the former being housed in a tube cast into the cylinder and head. The cylinder is of cast iron, which is well known for its longwearing qualities, but the head — in which cooling is more critical — is cast of aluminum. With the cooling fins running down, rather than around, the cylinder and head, and the breeze blowing directly into the top of the engine, cooling should be very good. One advantage of the horizontal-cylinder layout that should not be overlooked is that the upper valve gear is not shrouded by the tank, and it does not have its accessibility impaired by the frame. Also, the spark plug is right out where it can be reached.

The exterior of the engine and transmission are relatively clean. The oil pipes to the valve rockers are external, and the oil-return from the cylinder head is through an exposed tube, but apart from that, the engine is very tidy. That exposed oil return may prove to be something of a bother in cross-country events: it is right under the cylinder, and its position simply invites some unfriendly rock to knock it off. Frankly, we don’t know where else they could put it, but we do wish they had made a skidplate a standard feature on this machine. A skid plate would also serve to protect the sump, too, which is entirely exposed (no frame members extend down that far) to the batterings of random boulders. The exposed position of the sump does have its good points, though: the fact that it hangs out in the open keeps the engine/transmission oil drain and filler openings in the clear, and that simplifies service. And, with the engine hanging in the clear, one has only to pull the securing bolts that hold it up under the frame and the entire package drops right down into one’s waiting hands. From the standpoint of service, if no other, it is an altogether admirable arrangement.

Intake and exhaust plumbing on horizontal cylinders presents problems, but they have been very neatly solved on the Sprint H. The carburetor is mounted at a very steep downdraft angle, not more than 40 degrees from the vertical, and it is common for carburetors thus mounted to leak raw fuel into the engine from the idle passages. No sign of this ever appeared with the Sprint H; it could be left for hours with the fuel tap on, and when we returned to it, the engine would start without hesitation and idle as smoothly as a tractor.

Air filtration, essential on a machine that is intended for dirt riding, is handled by an efficient fiber-type Fram filter. The engine draws air from this through a long, flexible pipe, and a cast aluminum air horn smooths the flow into the carburetor. The air cleaner casing-end is held in place by a wing-nut, and we were pleased to see that this was safety-wired to insure that it would not unscrew and come off while riding. Such are the details that make a good motorcycle.

The exhaust pipe is of the upswept variety, coming out of the port and then curling up in front of the crankcase, running along the top of the transmission and out by the rear wheel. No heat-shield is provided; it isn’t needed, either. The pipe is tucked in so close that there is little chance of it getting against the rider’s leg. The exhaust pipe terminates in a muffler that incorporates a sort of “vortex extractor,” of which some Italian engineers are very fond. We are not sure it does anything, particularly, but it can’t do any harm, and we have seen them on Ferrari racing cars — a fact that may, or may not, prove anything. Car builders are notoriously illogical about exhaust systems.

Starting the Sprint H was, after the usual period of familiarization, very easy. There is a float tickler, to be used sparingly even when the engine is cold, and a choke slide — operated by a short rod extending from the top of the carburetor — that gave the best results when pushed completely down. A very few kicks would bring the engine around from cold; and once warm the engine seldom needed more than a single nudge. Fuel feed was through a 3-position valve (on, off and reverse) and the fuel line had crimped-on fittings, which should never leak or pull loose.

The fuel tank was small, holding only 2.6 gallons, instead of the 4 gallons contained in the present touringmodel tank, and was fastened to the frame through rubberbushed mounts. On many bikes, this fuel capacity would be too small — and we have complained about motorcycles on this score before — but the Sprint H delivered such excellent gasoline mileage (around 70 mpg under hard running) that it gave a respectable range.

The Sprint’s frame is, essentially, a single straight tube, with an o.d. of 23/8 inches. It starts at the steering head (where else?) and runs back and downward to the tubular structure that supports the spring/damper units. The spring/damper perches also indirectly support the back of the seat, and they taper around at the back to form a fender brace. At the forward ends of the structure, it ties into the engine mountings and the engine/transmission casing is further supported by a steel pressing that comes down from the backbone tube. It is light, simple and strong. And, for the Sprint H, there are additional diagonal braces around the spring/damper supports. These are not needed on the strictly road-going Sprint.

The suspension is, if memory serves us correctly, better than that of the Sprint we tested a year ago. The same system is used, with telescopic front forks and a swing-arm at the rear, but the springing seems a bit softer (and better suited to dirt riding), without being so soft that the bike becomes unsteady when riding fast on paved roads. The front forks are of aluminum, and neoprene boots, to exclude dust, are fitted around the sliding section at the top of the forks. They have been canted out at a steeper angle than the road version which increases the wheelbase by 11/3 inches and seems to aid handling somewhat. This contrasts oddly with the rear spring/damper units, which have dust covers on the road model, but are exposed on the Sprint H. Both suspensions, front and rear, have plenty of travel, and do not bottom except under the most outrageous pounding.

The rear fender stands a trifle close to the tire, but that over the front wheel has plenty of clearance. Unfortunately, the front fender is quite short, and only the rubber “mud-flap” tacked on the rear edge of the fender — seemingly as an after thought — keeps debris from the front wheel away from the cylinder head. The tires themselves are Pirellis, of the “trials universal” pattern, with a relatively smooth block tread. These are great on the road (much better than any knobby) and on fairly hard dirt surfaces, but when off in sand or loose dirt, there is a definite lack of traction. Under such conditions, there is no substitute for the cog-wheel effect of a knobby-tread tire, and that is the Sprint’s only shortcoming out in the dirt. It handles beautifully, and it will thunder out across hardpan like a rocket, but it sinks in a shower of sand if you get into a dry-wash. However, you can’t have everything, and as-delivered, the Sprint H is much better than average over a wide variety of surfaces.

Riding this lightweight, whether on dirt or pavement, was great fun. Except for a slight tendency to flutter the front wheel at 60-70 mph (an effect that can be cured by tightening the steering damper) it displayed exceptional handling. The brakes are large, and they are smooth and powerful, with the capacity for a succession of hard stops without fading. Plenty of torque is on tap, and the engine will crank-off the revolutions, too, so the Sprint H can be ridden in any fashion that takes one’s fancy: slogging along or turned up very tight. The handlebars are just right for touring, but a smidgin too short for hard riding in the dirt; the penalty that one pays for the dual nature of the machine. In all, the riding position would have been quite comfortable but for the saddle, which was just about 2 inches too narrow, and had a hard lump right at the critical point for a solo rider. Sliding forward gets you away from the lump, but it forces one into a less desirable position relative to the well-placed bars and pegs.

Instrumentation on the Sprint H consists of a speedometer and a tachometer. The English built Smiths tach gave accurate readings while it worked, which was not very long, and the speedometer showed a tendency to read fast in the middle speed range. It did, however, give good steady readings, with none of the annoying dancing that seems to afflict these instruments at higher speeds.

The control levers had ball-ends, a touch that should be required on all bikes, and the control cables themselves were about twice as stout as we usually see on lightweights. A thing we particularly liked — although we were not very impressed by them at first — were the large diameter handlebar grips. We also liked the rocker-type shift lever, which had a long throw, but was very smooth in its action. This lever would, however, sometimes refuse to nudge the transmission into 4th unless 3rd had been fully engaged on the previous shift. We do not remember any such bother with our earlier Sprint test machine, and this difficulty might well be peculiar to this specific bike; not a characteristic of all present Sprints.

We were pleasantly surprised with the Sprint, which was the first motorcycle to be given our new ½ mile acceleration to a timed-speed test, as it managed to get very near its absolute limit in the ½-mile. This would be expected in a big-inch bike, which would accelerate up to speed quickly. But, in a 15-incher, it was a surprise to get up to the flat-out point (minus about 5 mph) so quickly. If all bikes do as well, we will have no regrets about our change in procedure. •

HARLEY-DAVIDSON

SPRINT H

$720.00,

SPECIFICATIONS

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue