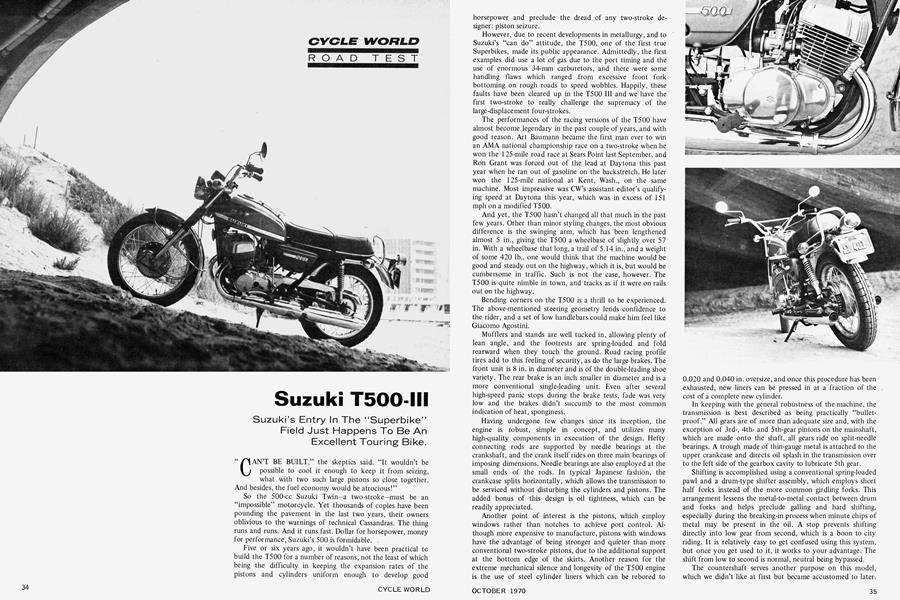

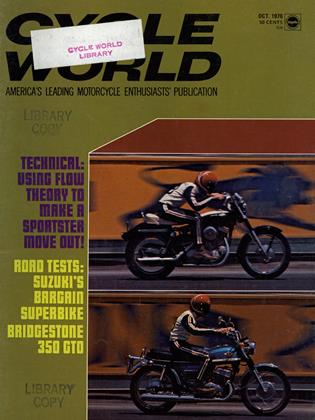

Suzuki T500-III

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

Suzuki's Entry In The "Superbike" Field Just Happens To Be An Excellent Touring Bike.

"CAN'T BE BUILT," the skeptics said. "It wouldn't be possible to cool it enough to keep it from seizing, what with two such large pistons so close together. And besides, the fuel economy would be atrocious!"

So the 500-cc Suzuki Twin-a two-stroke-must be an "impossible" motorcycle. Yet thousands of copies have been pounding the pavement in the last two years, their owners oblivious to the warnings of technical Cassandras. The thing runs and runs. And it runs fast. Dollar for horsepower, money for performance, Suzuki's 500 is formidable.

Five or six years ago, it wouldn't have been practical to build the T500 for a number of reasons, not the least of which being the difficulty in keeping the expansion rates of the pistons and cylinders uniform enough to develop good horsepower and preclude the dread of any two-stroke designer: piston seizure.

However, due to recent developments in metallurgy, and to Suzuki’s “can do” attitude, the T500, one of the first true Superbikes, made its public appearance. Admittedly, the first examples did use a lot of gas due to the port timing and the use of enormous 34-mm carburetors, and there were some handling flaws which ranged from excessive front fork bottoming on rough roads to speed wobbles. Happily, these faults have been cleared up in the T500 III and we have the first two-stroke to really challenge the supremacy of the large-displacement four-strokes.

The performances of the racing versions of the T500 have almost become legendary in the past couple of years, and with good reason. Art Baumann became the first man ever to win an AMA national championship race on a two-stroke when he won the 125-mile road race at Sears Point last September, and Ron Grant was forced out of the lead at Daytona this past year when he ran out of gasoline on the backstretch. He later won the 125-mile national at Kent, Wash., on the same machine. Most impressive was CW’s assistant editor’s qualifying speed at Daytona this year, which was in excess of 151 mph on a modified T500.

And yet, the T500 hasn’t changed all that much in the past few years. Other than minor styling changes, the most obvious difference is the swinging arm, which has been lengthened almost 5 in., giving the T500 a wheelbase of slightly over 57 in. With a wheelbase that long, a trail of 5.14 in., and a weight of some 420 lb., one would think that the machine would be good and steady out on the highway, which it is, but would be cumbersome in traffic. Such is not the case, however. The T500 is quite nimble in town, and tracks as if it were on rails out on the highway.

Bending corners on the T500 is a thrill to be experienced. The above-mentioned steering geometry lends confidence to the rider, and a set of low handlebars could make him feel like Giacomo Agostini.

Mufflers and stands are well tucked in, allowing plenty of lean angle, and the footrests are spring-loaded and fold rearward when they touch the ground. Road racing profile tires add to this feeling of security, as do the large brakes. The front unit is 8 in. in diameter and is of the double-leading shoe variety. The rear brake is an inch smaller in diameter and is a more conventional single-leading unit. Even after several high-speed panic stops during the brake tests, fade was very low and the brakes didn’t succumb to the most common indication of heat, sponginess.

Having undergone few changes since its inception, the engine is robust, simple in concept, and utilizes many high-quality components in execution of the design. Hefty connecting rods are supported by needle bearings at the crankshaft, and the crank itself rides on three main bearings of imposing dimensions. Needle bearings are also employed at the small ends of the rods. In typical Japanese fashion, the crankcase splits horizontally, which allows the transmission to be serviced without disturbing the cylinders and pistons. The added bonus of this design is oil tightness, which can be readily appreciated.

Another point of interest is the pistons, which employ windows rather than notches to achieve port control. Although more expensive to manufacture, pistons with windows have the advantage of being stronger and quieter than more conventional two-stroke pistons, due to the additional support at the bottom edge of the skirts. Another reason for the extreme mechanical silence and longevity of the T500 engine is the use of steel cylinder liners which can be rebored to 0.020 and 0.040 in. oversize, and once this procedure has been exhausted, new liners can be pressed in at a fraction of the cost of a complete new cylinder.

In keeping with the general robustness of the machine, the transmission is best described as being practically “bulletproof.” All gears are of more than adequate size and, with the exception of 3rd-, 4thand 5th-gear pinions on the mainshaft, which are made onto the shaft, all gears ride on split-needle bearings. A trough made of thin-gauge metal is attached to the upper crankcase and directs oil splash in the transmission over to the left side of the gearbox cavity to lubricate 5th gear.

Shifting is accomplished using a conventional spring-loaded pawl and a drum-type shifter assembly, which employs short half forks instead of the more common girdling forks. This arrangement lessens the metal-to-metal contact between drum and forks and helps preclude galling and hard shifting, especially during the breaking-in process when minute chips of metal may be present in the oil. A stop prevents shifting directly into low gear from second, which is a boon to city riding. It is relatively easy to get confused using this system, but once you get used to it, it works to your advantage. The shift from low to second is normal, neutral being bypassed.

The countershaft serves another purpose on this model, which we didn’t like at first but became accustomed to later. The end of this shaft drives both the tachometer and the oil pump, neither of which function when the clutch is pulled in. It doesn’t hurt anything, as there is sufficient oil still in the galleries to the engine to supply lubrication, but it was irritating not to be able to read the tachometer when the clutch was disengaged.

The oiling system in itself is quite ingenious, however, and does its job admirably. The pump is a variable displacement, plunger affair which increases the amount of oil in proportion to the throttle opening and the engine’s rpm. A cam which is synchronized to the throttle opens the pump progressively as the throttle is opened, regardless of the engine speed, thus supplying additional lubrication while climbing hills. It cuts back the supply when cruising on level ground or descending a hill, when less lubrication is required. Feed points include the two outer main bearings and the base of each cylinder. Oil used to lubricate the main bearings then mixes with the incoming fuel/air mixture, sprays across the slotted rods to lubricate those bearings and is burned and ejected through the exhaust pipes. The center main bearing is lubricated by oil from the transmission. Cylinder walls and the wrist pin bearings are lubricated by the other two orifices. Oil consumption on our test machine was surprisingly low considering the few miles it had on it.

In addition to redesigned port timing, the newer T500’s are fitted with 32-mm Mikuni carburetors which seem to work just as well as their larger brothers, installed on the first T500’s. In working with the different port configuration they add significantly to the fuel economy.

During a phase of our test, we logged almost 150 miles and used only 3 gal. of gas, an average of almost 50 mpg! Some credit must be given to the combination of port timing and the rather low corrected compression ratio of 6.6:1, which made the T500 most pleasant to ride in traffic.

Some vibration is still evident in the latest model, but due to its relatively low frequency, it is more relaxing than annoying: somewhat akin to a vibro-massage chair. Handlebars, tachometer and speedometer, taillight and the engine are all mounted in rubber and help quell the shaking to a great extent, although we were never able to ignore it completely.

Most of the machine’s increase in weight comes from the frame, which is constructed of thick-wall tubing and substantial gusseting, and is of the conventional double cradle design. The swinging arm is cross-braced several inches behind the pivot shaft and looks very strong. The entire unit appears indestructable. Welds are somewhat cruder in appearance than we’ve come to expect, but penetration appears to be very good. Paint is well applied and lustrous on the frame as well as the tank and side covers, and an abundance of chrome and polished aluminum help make the T500 one of the classiest machines on the road. We also liked the chrome handrail behind the seat and the grab strap in the middle of the seat, giving the passenger a minimum of three places to hang on. We weren’t as pleased with the chrome plated parcel rack on the tank, however, and the cross brace between the handlebars seems quite unnecessary.

Our “like list” was much larger. Controls all worked well, seating position was comfortable for all of our staff members, lighting was excellent and the turn signals are an item that we’re finding harder and harder to do without. A better-thanaverage toolkit is supplied, and wiring is up to typical Japanese standards. A friction-type steering damper is fitted but was never used after applying a very slight drag to it.

Exhaust silencing is very good, but the aircleaner emitted a throaty roar when the throttle was opened wide, which tended to be somewhat annoying at first. We gradually got used to it and accepted the din as part of the machine’s character.

Ease of maintenance and attention to detail were also big plus factors with our staff. The engine is quite simple mechanically, and everything that might need routine adjustment was easy to get to. Only three screws need be removed to expose the entire generator assembly and the ignition points. Carburetors are accessible and the aircleaner is a snap to get off to clean. Even the folding kickstarter lever has a grease fitting on it.

On the debit side, we found that the overall gear ratio was a little “tall” for average riding conditions. It is true that high speed touring is the T500’s forte, but it was necessary to slip the clutch quite a bit to get the model under way in town, and it was decidedly sluggish coming off the line in our acceleration tests. According to the folks at U.S. Suzuki, many dealers are installing a 14-tooth countershaft sprocket, which is one tooth less than standard, on all their T500’s before they leave the shop. Nothing seems to suffer, and overall performance is improved considerably.

Needless to say, the people who said it “couldn’t be built” are keeping pretty quiet these days. Not only was it built, but it has been an almost unqualified success in all respects. And, with a suggested retail price of $899, it has to be one of the best touring motorcycle bargains going. 0]

Suzuki

T500-III

$899

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Department

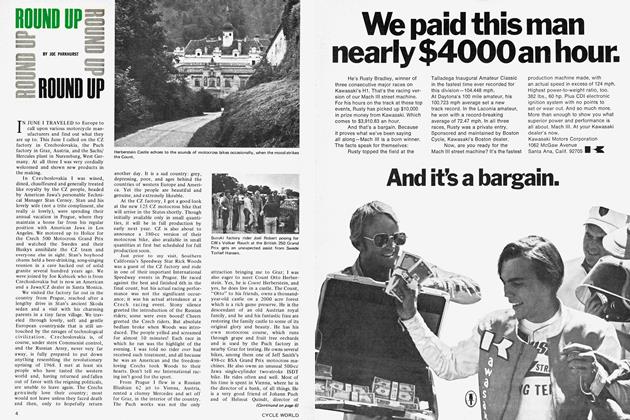

DepartmentRound Up

October 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

October 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Special Technical Feature

Special Technical FeatureTechnical: the Flow Theory Way To Make A Sportster Go!

October 1970 By Jody Nicholas -

Features

FeaturesOldies But Goodies: Cycles & Sayings

October 1970 By Publilius Syrus -

Features

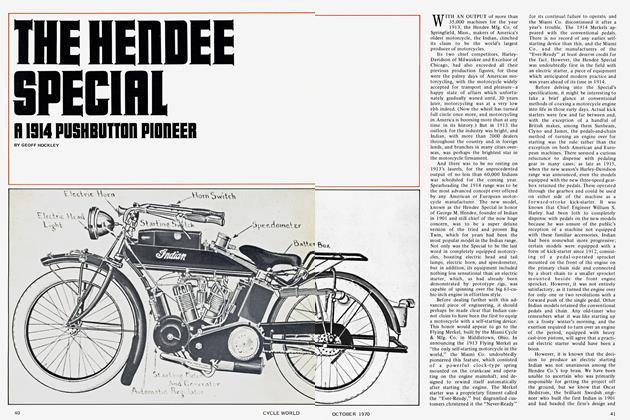

FeaturesThe Hendee Special

October 1970 By Geoff Hockley