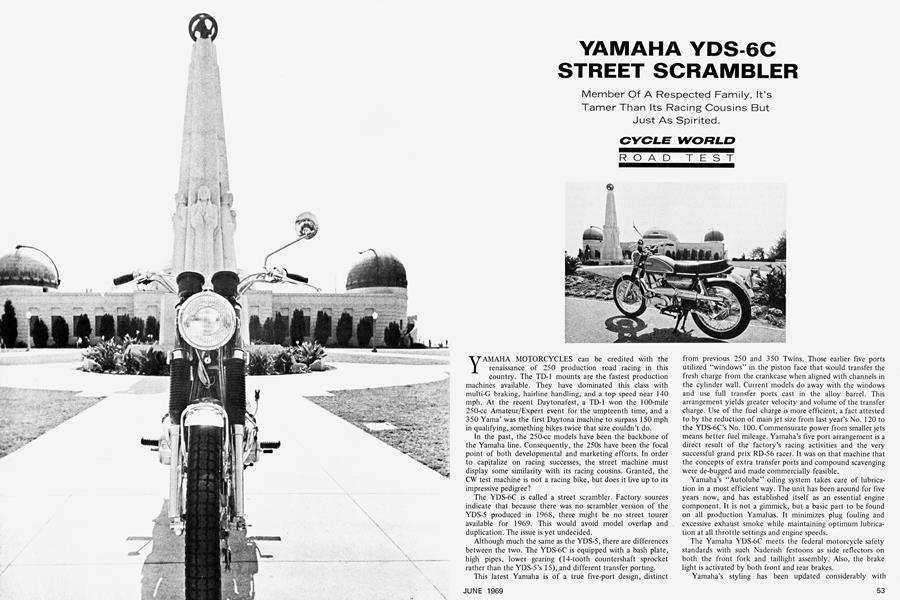

YAMAHA YDS-6C STREET SCRAMBLER

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

Member Of A Respected Family, It's Tamer Than Its Racing Cousins But Just As Spirited.

YAMAHA MOTORCYCLES can be credited with the renaissance of 250 production road racing in this country. The TD-1 mounts are the fastest production machines available. They have dominated this class with multi-G braking, hairline handling, and a top speed near 140 mph. At the recent Daytonafest, a TD-1 won the 100-mile 250-cc Amateur/Expert event for the umpteenth time, and a 350 Yama’ was the first Daytona machine to surpass 150 mph in qualifying, something bikes twice that size couldn’t do.

In the past, the 250-cc models have been the backbone of the Yamaha line. Consequently, the 250s have been the focal point of both developmental and marketing efforts. In order to capitalize on racing successes, the street machine must display some similarity with its racing cousins. Granted, the CW test machine is not a racing bike, but does it live up to its impressive pedigree?

The YDS-6C is called a street scrambler. Factory sources indicate that because there was no scrambler version of the YDS-5 produced in 1968, there might be no street tourer available for 1969. This would avoid model overlap and duplication. The issue is yet undecided.

Although much the same as the YDS-5, there are differences between the two. The YDS-6C is equipped with a bash plate, high pipes, lower gearing (14-tooth countershaft sprocket rather than the YDS-5’s 15), and different transfer porting.

This latest Yamaha is of a true five-port design, distinct from previous 250 and 350 Twins. Those earlier five ports utilized “windows” in the piston face that would transfer the fresh charge from the crankcase when aligned with channels in the cylinder wall. Current models do away with the windows and use full transfer ports cast in the alloy barrel. This arrangement yields greater velocity and volume of the transfer charge. Use of the fuel charge is more efficient, a fact attested to by the reduction of main jet size from last year’s No. 120 to the YDS-6C’s No. 100. Commensurate power from smaller jets means better fuel mileage. Yamaha’s five port arrangement is a direct result of the factory’s racing activities and the very successful grand prix RD-56 racer. It was on that machine that the concepts of extra transfer ports and compound scavenging were de-bugged and made commercially feasible.

Yamaha’s “Autolube” oiling system takes care of lubrication in a most efficient way. The unit has been around for five years now, and has established itself as an essential engine component. It is not a gimmick, but a basic part to be found on all production Yamahas. It minimizes plug fouling and excessive exhaust smoke while maintaining optimum lubrication at all throttle settings and engine speeds.

The Yamaha YDS-6C meets the federal motorcycle safety standards with such Naderish festoons as side reflectors on both the front fork and taillight assembly. Also, the brake light is activated by both front and rear brakes.

Yamaha’s styling has been updated considerably with pleasing results. The speedometer and tachometer no longer share the same location on the headlight nacelle. They are now separate units. The two meters benefit from this as the dials are larger, with smaller increments, and are much easier to read at a glance. The redesigned fuel tank is smaller (2.9 vs. 4.0 gal.) but is easier on the eyes than the YDS-5’s bulbous, chromed container. The spacious tuck and roll seat and the restyled upswept pipes are new, too. The cooling fins have been squared off and the engine’s side covers are polished aluminum rather than painted silver. Overall effect of this restyling makes the bike appear much leaner than previous models, while external dimensions remain much the same.

The seating position is not very comfortable for taller riders. The seat itself is wide and soft, no complaint there; but the footpeg and handlebar locations cause the rider to sit somewhat forward and bolt upright. Beside being uncomfortable, this position is not the best for weight distribution at high speeds.

The battery-coil ignition system was trouble free throughout the test. After long periods of idling the engine never missed a beat when wound out all the way. Warm starts seldom needed more than one kick, while cold starts rarely called for more than two. Warm-ups took less and less time as miles accumulated and the machine loosened up. And, with the exception of the first 30 miles or so, engine temperature was moderate and stable in spite of very hard riding. Piston clearance in iron liners is a snug 0.0014-0.0016 in., which means that the first few miles of engine operation are very important. Take it easy for that period and give the reciprocating parts an opportunity to bed-in, and the engine should buzz happily thereafter. Yamaha’s extensive racing experience has qualified it for near papal infallibility in the fields of engine design and choice of materials. Consequently, a correctly set up Yamaha will show minimal temperamentality even when abused. On the other hand, times does not permit CW testers to observe breaking-in procedures. Our test bike was flogged constantly and it bore the abuse nobly without complaint.

Typical of high performance two-strokes, the 246-cc engine is peaky. Power comes in with a great rush at 5000 rpm and extends to the 7500 mark. With less than 60 miles on the odometer, the engine would rev to its 8400-rpm redline in the first four gears. Gear ratios are excellently chosen. From its 1100-1200-rpm idle the bike will power away without elaborate clutching and throttling. While drag strip starts necessitate clutch slipping to avoid such unpleasantries as wheelies and bogging, the bike would nonetheless insist upon leaving a few feet of rubber. Full throttle shifts into second gear consistently separated the front wheel from the pavement.

The gear box was indecisive at times, delivering an occasional neutral even though the shift lever was seemingly snicked up to its stop. This situation would occur when the bike was ridden easily. As the test progressed, this annoying tendency became increasingly rare. This leads us to believe that it was due to clutch drag and the tight newness of the transmission. As the seven-plate clutch began to wear in, the racing heritage of the clutch and transmission became more evident. They are capable of absorbing terrific abuse with an almost spiritual resignation. One reason for this is the use of six torsion springs in the clutch shell. These springs absorb shock loadings imparted to the clutch through the geared primary drive. The drive train is further insulated from impulses by a conventional vane/rubber biscuit shock absorber in the rear sprocket.

There is little to be said of our test bike’s brakes except that they are excellent. The front unit is a twin-cammer that allows faultless control and sensitivity. The rear brake is just as good in that respect. Straight line stops from 80 mph are no problem. Under very hard braking there is no tail wagging or skipping from the rear tire. In spite of sudden forward weight transfer it stays firmly on the ground. Racing most definitely improves the breed as evidenced by these stoppers.

Handling, too, is very good. The Yamaha was ridden hard into sweeping turns and leaned way over with no sign of instability.

Upshifting, down shifting, and braking in the middle of fast turns revealed no wobbles, shudders, or similarly poor manners. In all situations the bike retains that characteristic electric motor smoothness. With its high pipes, lower gearing, and 6.0-in. ground clearance, the bike is amenable to an occasional foray off the road, although its 319-lb. curb weight will frustrate most competitive efforts. This is not new; the Big Bears were bugabooed by overweight too. However, the YDS-6C has lost a good 20 lb. in the last year and its handling, particularly at lower speeds, has benefited accordingly.

This machine can be used for daily transportation (65-mph cruising speed). But more than that, it is a machine for the man who likes to ride. Not only to potter about, but to ride it hard and wring it out; to shift, to brake and to accelerate; in short, to ride with it, not on it. Ride it hard and it repays you with clairvoyant obedience. [Oj

YAMAHA YDS-6C STREET SCRAMBLER

$655

PECiFICATiOt~.~

jt~1fi!i~t[[ø~i

tJi~t~

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Round Up

June 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

The Scene

June 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

The Service Department

June 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1969 -

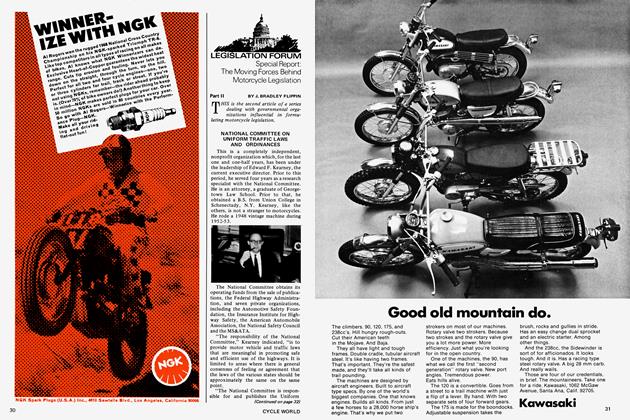

Legislation Forum

Legislation ForumSpecial Report: the Moving Forces Behind Motorcycle Legislation

June 1969 By J. Bradley Flippin -

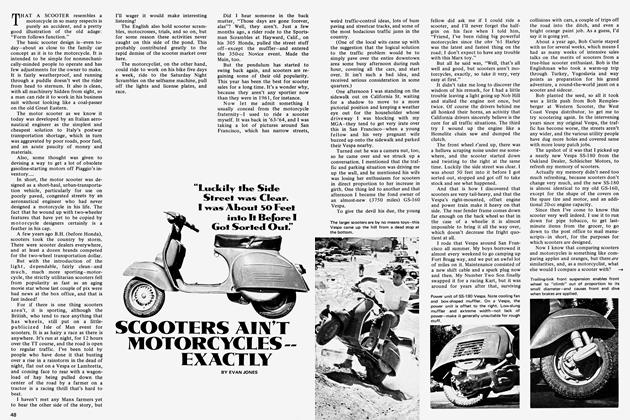

Offshoot Dept.

Offshoot Dept.Scooters Ain't Motorcycles-- Exactly

June 1969 By Evan Jones