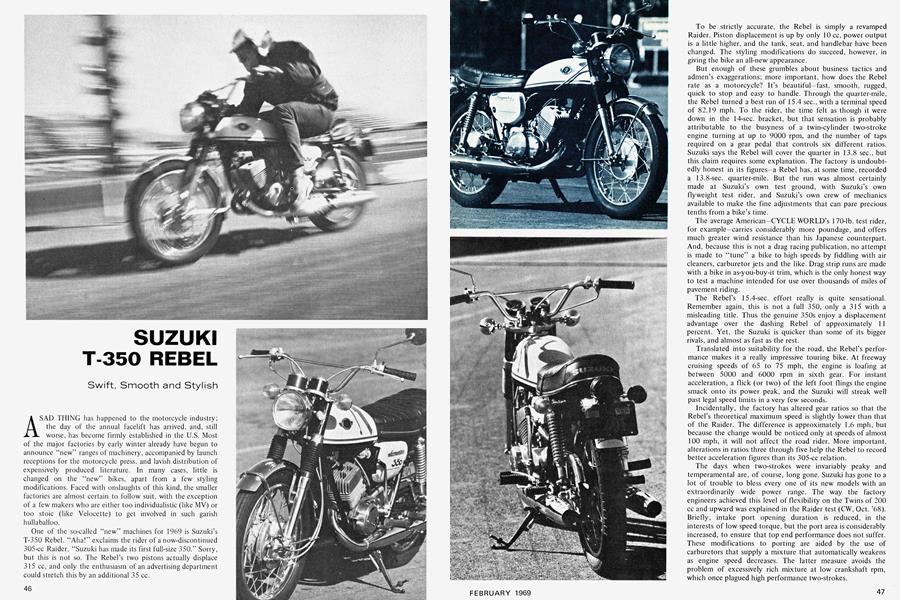

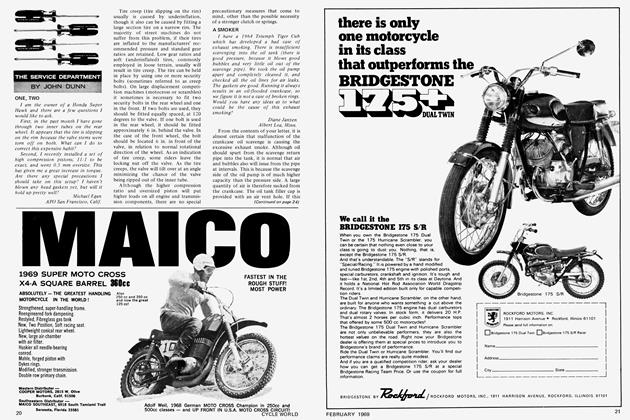

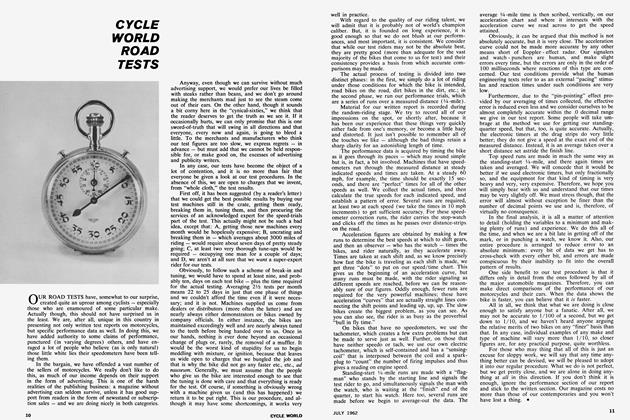

SUZUKI T-350 REBEL

Swift, Smooth and Stylish

A SAD THING has happened to the motorcycle industry; the day of the annual facelift has arrived, and, still worse, has become firmly established in the U.S. Most of the major factories by early winter already have begun to announce "new" ranges of machinery, accompanied by launch receptions for the motorcycle press, and lavish distribution of expensively produced literature. In many cases, little is changed on the "new" bikes, apart from a few styling modifications. Faced with onslaughts of this kind, the smaller factories are almost certain to follow suit, with the exception of a few makers who are either too individualistic (like MV) or too stoic (like Velocette) to get involved in such garish hullaballoo.

One of the so-called "new" machines for 1969 is Suzuki's T-350 Rebel. "Aha!" exclaims the rider of a now-discontinued 305-cc Raider, "Suzuki has made its first full-size 350." Sorry, but this is not so. The Rebel's two pistons actually displace 315 cc, and only the enthusiasm of an advertising department could stretch this by an additional 35 cc.

To be strictly accurate, the Rebel is simply a revamped Raider. Piston displacement is up by only 10 cc, power output is a little higher, and the tank, seat, and handlebar have been changed. The styling modifications do succeed, however, in giving the bike an all-new appearance.

But enough of these grumbles about business tactics and admen’s exaggerations; more important, how does the Rebel rate as a motorcycle? It’s beautiful -fast, smooth, rugged, quick to stop and easy to handle. Through the quarter-mile, the Rebel turned a best run of 15.4 sec., with a terminal speed of 82.19 mph. To the rider, the time felt as though it were down in the 14-sec. bracket, but that sensation is probably attributable to the busyness of a twin-cylinder two-stroke engine turning at up to 9000 rpm, and the number of taps required on a gear pedal that controls six different ratios. Suzuki says the Rebel will cover the quarter in 13.8 sec., but this claim requires some explanation. The factory is undoubtedly honest in its figures—a Rebel has, at some time, recorded a 13.8-sec. quarter-mile. But the run was almost certainly made at Suzuki’s own test ground, with Suzuki’s own flyweight test rider, and Suzuki’s own crew of mechanics available to make the fine adjustments that can pare precious tenths from a bike’s time.

The average American—CYCLE WORLD’S 170-lb. test rider, for example—carries considerably more poundage, and offers much greater wind resistance than his Japanese counterpart. And, because this is not a drag racing publication, no attempt is made to “tune” a bike to high speeds by fiddling with air cleaners, carburetor jets and the like. Drag strip runs are made with a bike in as-you-buy-it trim, which is the only honest way to test a machine intended for use over thousands of miles of pavement riding.

The Rebel’s 15.4-sec. effort really is quite sensational. Remember again, this is not a full 350, only a 315 with a misleading title. Thus the genuine 350s enjoy a displacement advantage over the dashing Rebel of approximately 11 percent. Yet, the Suzuki is quicker than some of its bigger rivals, and almost as fast as the rest.

Translated into suitability for the road, the Rebel’s performance makes it a really impressive touring bike. At freeway cruising speeds of 65 to 75 mph, the engine is loafing at between 5000 and 6000 rpm in sixth gear. For instant acceleration, a flick (or two) of the left foot flings the engine smack onto its power peak, and the Suzuki will streak well past legal speed limits in a very few seconds.

Incidentally, the factory has altered gear ratios so that the Rebel’s theoretical maximum speed is slightly lower than that of the Raider. The difference is approximately 1.6 mph, but because the change would be noticed only at speeds of almost 100 mph, it will not affect the road rider. More important, alterations in ratios three through five help the Rebel to record better acceleration figures than its 305-cc relation.

The days when two-strokes were invariably peaky and temperamental are, of course, long gone. Suzuki has gone to a lot of trouble to bless every one of its new models with an extraordinarily wide power range. The way the factory engineers achieved this level of flexibility on the Twins of 200 cc and upward was explained in the Raider test (CW, Oct. ’68). Briefly, intake port opening duration is reduced, in the interests of low speed torque, but the port area is considerably increased, to ensure that top end performance does not suffer. These modifications to porting are aided by the use of carburetors that supply a mixture that automatically weakens as engine speed decreases. The latter measure avoids the problem of excessively rich mixture at low crankshaft rpm, which once plagued high performance two-strokes.

These changes aid the Rebel in the same way that they transformed the Raider. Power feeds in smoothly from as low as 2000 rpm, with little fuss or kickback, and really usable urge starts as low as 4000 rpm. If it had to, the Rebel could manage quite easily with only five gears.

Along with the styling changes, Suzuki has given the Rebel new color schemes. The test bike featured an ivory tank and side panels, with a red stripe along the lower edge of the tank—a very fetching match. Also available is a blue-withwhite-stripe arrangement. The new tank appears longer, lower, and slimmer than the Raider version, while the seat is a baroquely quilted affair, but very comfortable, and thickly padded.

Streamlining of the tank has done more than improve its looks; its capacity also has been reduced-to 3.0 gal. That sounds reasonable, until it’s remembered that sporty twostroke Twins are thirsty devils, with no regard for a man’s

pocket or the distance between service stations on littletraveled roads. In other words, the tank capacity is pitifully incompatible with the Rebel’s performance and fuel demands. American riders are no strangers to long distance hauls that are measured in thousands, rather than hundreds, of miles. But, if such a journey is attempted on a Rebel equipped with a standard tank, high average speeds will be socked in the eye by the delays at service stations while four-door armchairs get bloated on 20-gal. mouthfuls of fuel.

Similarly, the handlebar is great for trundling downtown, but not such a good idea for prolonged high speeds. The Rebel will thrum along tirelessly, seemingly forever, but motorcyclists are human, and will tire of that wind-buffeted upright riding position long before the Suzuki is ready to quit. However, criticisms of this kind probably should be directed more at riders than at manufacturers. Small tanks and high bars apparently sell motorcycles, even though they hamper performance and foul up long trips.

Suzuki also has tamed another traditional bugbear of high-revving two-strokes—high frequency vibration. The Rebel can be thrashed to peak rpm without any lunatic oscillations of handlebar tips, footpegs, or seat interfering with the pilot’s concentration. Again, advances in two-stroke technology enable Suzuki to reduce clearances between pistons and cylinder walls. This results in a reduction in the ringing and pinging that once accompanied quick two-strokes. In fact, the Rebel is a pleasantly quiet machine, helped by a pair of long, chromed silencers. The exhaust note is a mellow yowl that is easy to control in city streets.

A standout feature of the Rebel is its impeccable set of brakes. The front unit is a two leading shoe affair, and the rear brake features conventional single-cam operation. And, though both are no more than average in drum and lining dimensions, they provide phenomenal stopping powers—a halt from 60 mph in less than 120 ft., for example. This fierce power is mated with fine sensitivity, so that it’s possible to execute stops smoothly, without grab or judder. Moreover, the front brake refuses to lock the wheel. The tire will squeal a violent protest—but it won’t stop turning.

A typically Japanese frame holds everything tautly in place. Apart from the two front downtubes, the frame is hardly apparent behind the engine, tank, seat, and transmission. But have no doubt about its efficiency. Solidly constructed of generously-sized tubing, it possesses plenty of strengthening braces and gussets. High speed cornering becomes effortless; no flexing or pitching upsets the chosen line. The Rebel weighs 323 lb., with a half-tank of fuel, which makes it 9 lb. lighter than the Raider.

The frame is painted black, but almost everything else on the machine, apart from the tank and side panels, is finished either in gleaming chrome or polished alloy. Instrumentation is comprised of Suzuki’s customary tachometer and speedometer, mounted directly in front of the rider, with no cables or handlebar struts to obstruct vision. A pair of large, amber indicator lights is provided at each end of the machine, and help to make automobile drivers aware that the Suzuki is there. The operating switch, however, too easily can be flicked from one position, straight through “neutral,” to the other position. The movement should be less delicate, and more positive, to lessen the chance of making inadvertent signals.

Small tank, high bars, fussy indicator switch, all are criticisms that are forgiven in the Rebel’s case, however. Six speeds, a turbine-like powerplant, and sophisticated Posi-Force oil injection are very real bargains for a suggested retail price of less than $800. The Rebel is more than a stornier, it’s a swinger.

SUZUKI T-350 REBEL

SPECIFICATIONS

$792

PERFORMANCE