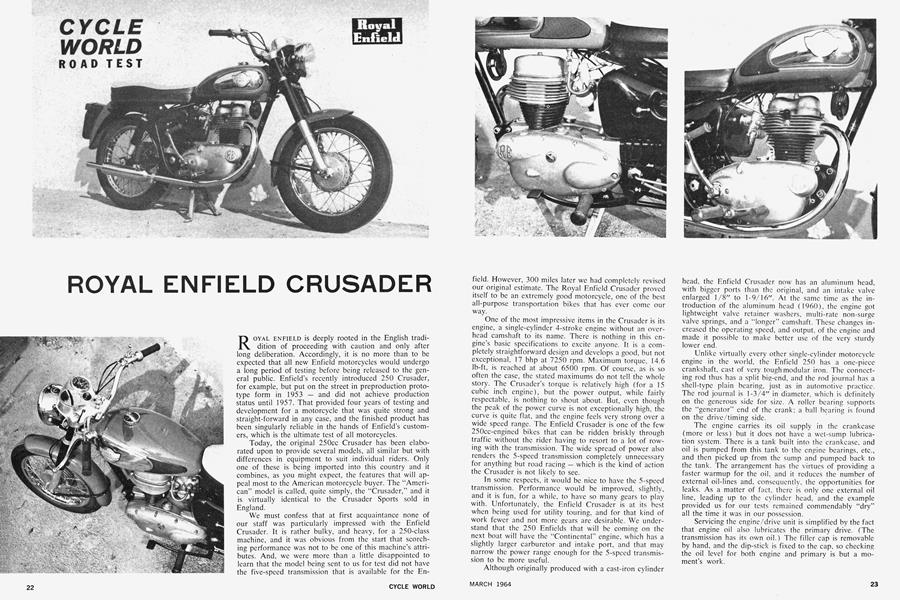

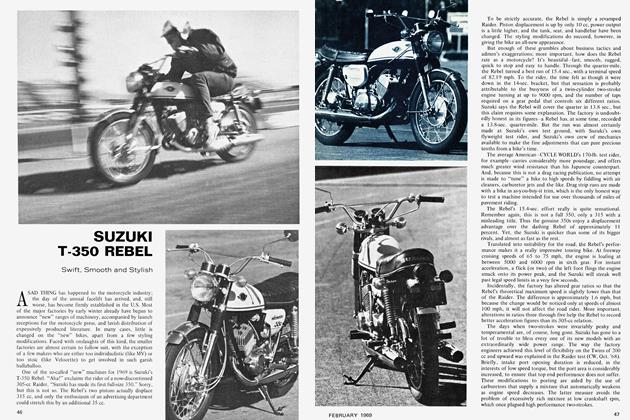

ROYAL ENFIELD CRUSADER

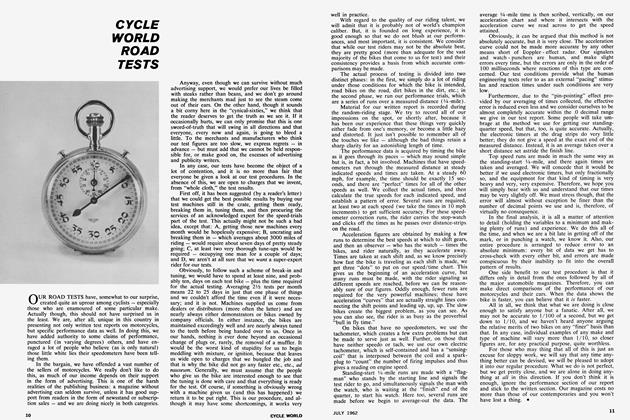

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

ROYAL ENFIELD is deeply rooted in the English tradidition of proceeding with caution and only after long deliberation. Accordingly, it is no more than to be expected that all new Enfield motorcycles would undergo a long period of testing before being released to the general public. Enfield's recently introduced 250 Crusader, for example, but put on the street in preproduction prototype form in 1953 — and did not achieve production status until 1957. That provided four years of testing and development for a motorcycle that was quite strong and straight-forward in any case, and the finished product has been singularly reliable in the hands of Enfield's customers, which is the ultimate test of all motorcycles.

Today, the original 250cc Crusader has been elaborated upon to provide several models, all similar but with differences in equipment to suit individual riders. Only one of these is being imported into this country and it combines, as you might expect, the features that will appeal most to the American motorcycle buyer. The “American” model is called, quite simply, the “Crusader,” and it is virtually identical to the Crusader Sports sold in England.

We must confess that at first acquaintance none of our staff was particularly impressed with the Enfield Crusader. It is rather bulky, and heavy, for a 250-class machine, and it was obvious from the start that scorching performance was not to be one of this machine's attributes. And, we were more than a little disappointed to learn that the model being sent to us for test did not have the five-speed transmission that is available for the Enfield. However, 300 miles later we had completely revised our original estimate. The Royal Enfield Crusader proved itself to be an extremely good motorcycle, one of the best all-purpose transportation bikes that has ever come our way.

One of the most impressive items in the Crusader is its engine, a single-cylinder 4-stroke engine without an overhead camshaft to its name. There is nothing in this engine’s basic specifications to excite anyone, it is a completely straightforward design and develops a good, but not exceptional, 17 bhp at 7250 rpm. Maximum torque, 14.6 lb-ft, is reached at about 6500 rpm. Of course, as is so often the case, the stated maximums do not tell the whole story. The Crusader’s torque is relatively high (for a 15 cubic inch engine), but the power output, while fairly respectable, is nothing to shout about. But, even though the peak of the power curve is not exceptionally high, the curve is quite flat, and the engine feels very strong over a wide speed range. The Enfield Crusader is one of the few 250cc-engincd bikes that can be ridden briskly through traffic without the rider having to resort to a lot of rowing with the transmission. The wide spread of power also renders the 5-spced transmission completely unnecessary for anything but road racing — which is the kind of action the Crusader is not likely to see.

In some respects, it would be nice to have the 5-specd transmission. Performance would be improved, slightly, and it is fun, for a while, to have so many gears to play with. Unfortunately, the Enfield Crusader is at its best when being used for utility touring, and for that kind of work fewer and not more gears are desirable. We understand that the 250 Enfields that will be coming on the next boat will have the “Continental" engine, which has a slightly larger carburetor and intake port, and that may narrow the power range enough for the 5-specd transmission to be more useful.

Although originally produced with a cast-iron cylinder head, the Enfield Crusader now has an aluminum head, with bigger ports than the original, and an intake valve enlarged 1/8" to 1-9/16". At the same time as the introduction of the aluminum head (1960), the engine got lightweight valve retainer washers, multi-rate non-surge valve springs, and a “longer” camshaft. These changes increased the operating speed, and output, of the engine and made it possible to make better use of the very sturdy lower end.

Unlike virtually every other single-cylinder motorcycle engine in the world, the Enfield 250 has a one-piece crankshaft, cast of very tough modular iron. The connecting rod thus has a split big-end, and the rod journal has a shell-type plain bearing, just as in automotive practice. The rod journal is 1-3/4" in diameter, which is definitely on the generous side for size. A roller bearing supports the “generator” end of the crank; a ball bearing is found on the drive/timing side.

The engine carries its oil supply in the crankcase (more or less) but it does not have a wet-sump lubrication system. There is a tank built into the crankcase, and oil is pumped from this tank to the engine bearings, etc., and then picked up from the sump and pumped back to the tank. The arrangement has the virtues of providing a faster warmup for the oil, and it reduces the number of external oil-lincs and, consequently, the opportunities for leaks. As a matter of fact, there is only one external oil line, leading up to the cylinder head, and the example provided us for our tests remained commendably “dry” all the time it was in our possession.

Servicing the engine/drive unit is simplified by the fact that engine oil also lubricates the primary drive. (The transmission has its own oil.) The filler cap is removable by hand, and the dip-stick is fixed to the cap, so checking the oil level for both engine and primary is but a moment’s work.

One item of service that many owners will find bothersome, but should be done regularly, is the cleaning and replacement of the engine's two oil filters. There is a felt filter under a round cover on the left upper side of the crankcase, and the owner's manual asks that this be removed and cleaned at 2000 mile intervals, and replaced after 5000 miles. Another filter, made of metal gauze, is located up in the forward end of the primary case, the cover of which must be removed for service. The manual specifies that this filter be cleaned at 2000 mile intervals. We applaud the use of good filters in the oil system, which are essential to long engine life, but we wonder if motorcycle manufacturers will ever adopt the effective and convenient screw-on cartridges now common in automobiles.

In sharp contrast with the almost fanatical concern with filtering the oil, the engine is allowed to breathe into the carburetor anything that might be airborne and in the area. There is not even the pretense of a gravel-strainer filter, which would at least prevent the engine from ingesting coarse sand and small, low-flying birds.

No reserve is provided in the fuel system, and this is a serious lack. The engine burns so little fuel, even when cruising at 60 mph, that the cruising range is good, but when the fuel is gone, it is gone to the last drop. And, with the fuel filler located in the center of the tank top. a peek in only shows the rider the top of the ridge in the tank's bottom that provides clearance for the frame. It is all but impossible to see the fuel level after it falls below the half-full point. Some of the curse is removed from this arrangement by the fact that the bike is equipped with a trip-meter on the speedometer head. This can be reset when the tank is filled (by pulling down and twisting a long wand) and with experience, the rider will know how many miles he may safely ride before a refill is necessary.

The overall construction and finish of the Crusader makes a good impression. The frame is all of steel tubing and plate, and welded together. There are none of the heavy cast-iron lugs seen on most English machines. The welds, incidentally, look good enough to have been made in America, and even the paint on the frame is good. The only points where the finish was less than good were at the engine cases, which were in as-cast condition, and in the fuel tank’s side plates, which are chromed snap-on pressings that do nothing for the bike's appearance.

In keeping with the Crusader’s basic character, we did most of our test riding on pavement, mixing the mileage between town and country riding. Perhaps the most important thing we discovered was that the Crusader would be ready to crusade after only a couple of prods at the kick lever whether hot or cold. Indeed, most of the time, one gentle jab was enough to bring the engine to life. On the Crusader, an electric starter would be largely wasted.

Riding comfort was quite good. The seat is wide, soft and long, and riders of all sizes will find some place along it where the handlebars arc a perfect reach. The bars are, we arc happy to report, at precisely the right height for comfortable cruising; they are too low for scrambles, of course, and too high for road racing — but who cares? There is a neutral indicator on the side of the transmission casing, but on our test machine it did not indicate properly. This small flaw did not bother us much; the shift mechanism is so smooth, and positive, that it is a snap to find neutral just by feeling with one's toe. Catching neutral is so easy, in fact, that we soon fell into the habit of slipping the box into neutral as we approached a stop.

Performance was fairly good; very good for a rather heavy and tail-geared 250. The bike doesn't blast up to speed, but it pulls with smoothness and determination, and it docs get along briskly. More important, it will cruise along at 60-65 mph without feeling strained, and that is not a quality that comes with every 250cc bike.

Handling was quite good. The steering is sensitive and quick, perhaps because the fork angle is" steep and there is no damper. Almost enough steering lock is provided to make the Crusader suitable as a trials machine. Unless considerably modified, it will not make much of a scrambler. We tried a run in the dirt, and the front wheel felt as though it was mounted on a caster, with no connection between it and the handlebars.

Whatever shortcomings the Royal Enfield Crusader may have as a scrambler, dragster or road racer, it is a very fine utility touring bike. It always starts easily, and it is strong enough (and feels like it) so that the rider never gives a thoueht to the possibilitv of a break-down. The bike provided for our tests was flogged unmercifully at times, and it showed not the least""sign of distress over being worked so furiously. To reinforce the impression of great reliability that we gained from the bike itself, there arc the reports from people who ride an Enfield 250 every dav: they apparently never show their faces at the local shop unless they need a spark phi" or an oil change. •

ROYAL ENFIELD CRUSADER

$679.00

View Full Issue

View Full Issue