GREEVES CHALLENGER

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

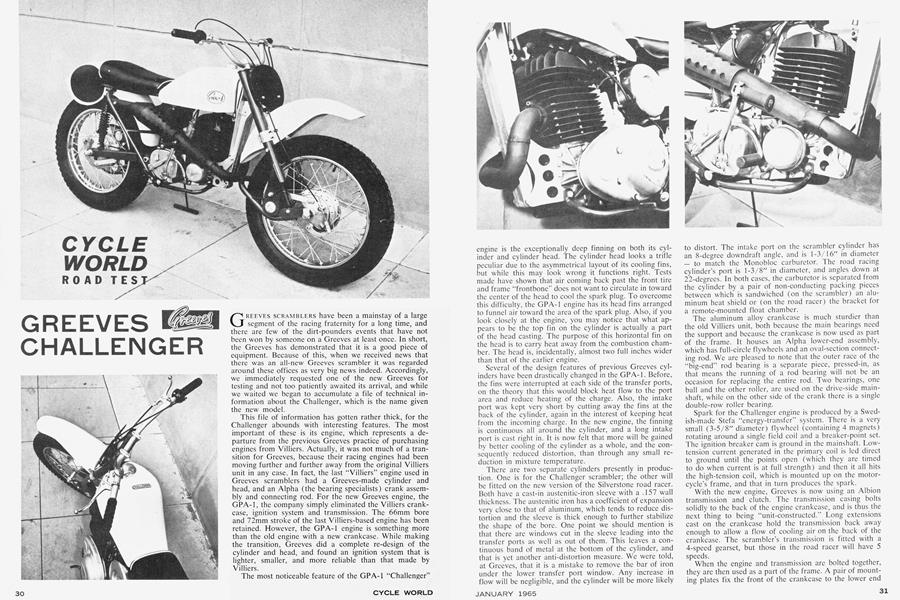

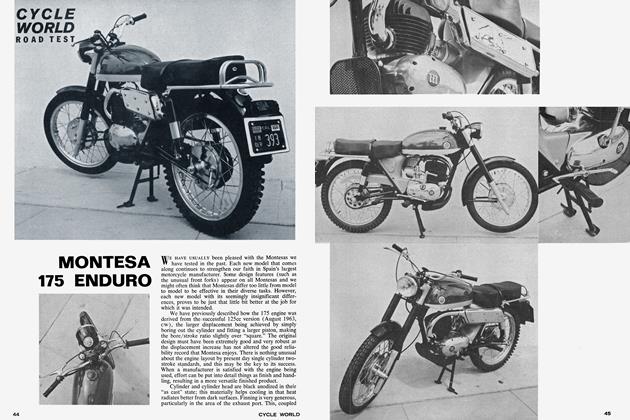

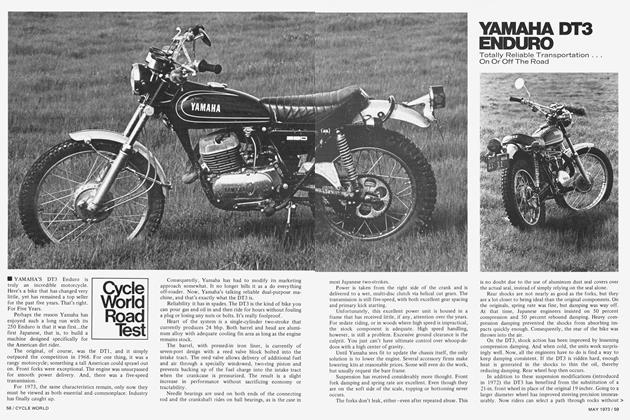

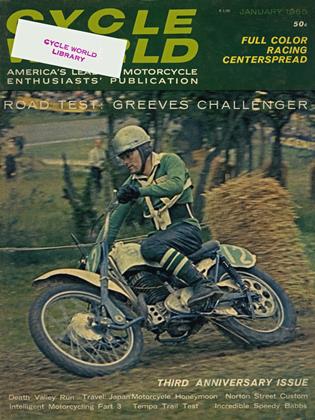

GREEVES SCRAMBLERS have been a mainstay of a large segment of the racing fraternity for a long time, and there are few of the dirt-pounders events that have not been won by someone on a Greeves at least once. In short, the Greeves has demonstrated that it is a good piece of equipment. Because of this, when we received news that there was an all-new Greeves scrambler it was regarded around these offices as very big news indeed. Accordingly, we immediately requested one of the new Greeves for testing and not too patiently awaited its arrival, and while we waited we began to accumulate a file of technical information about the Challenger, which is the name given the new model.

This file of information has gotten rather thick, for the Challenger abounds with interesting features. The most important of these is its engine, which represents a departure from the previous Greeves practice of purchasing engines from Villiers. Actually, it was not much of a transition for Greeves, because their racing engines had been moving further and further away from the original Villiers unit in any case. In fact, the last “Villiers” engine used in Greeves scramblers had a Greeves-made cylinder and head, and an Alpha (the bearing specialists) crank assembly and connecting rod. For the new Greeves engine, the GPA-1, the company simply eliminated the Villiers crankcase, ignition system and transmission. The 66mm bore and 72mm stroke of the last Villiers-based engine has been retained. However, the GPA-1 engine is something more than the old engine with a new crankcase. While making the transition, Greeves did a complete re-design of the cylinder and head, and found an ignition system that is lighter, smaller, and more reliable than that made by Villiers.

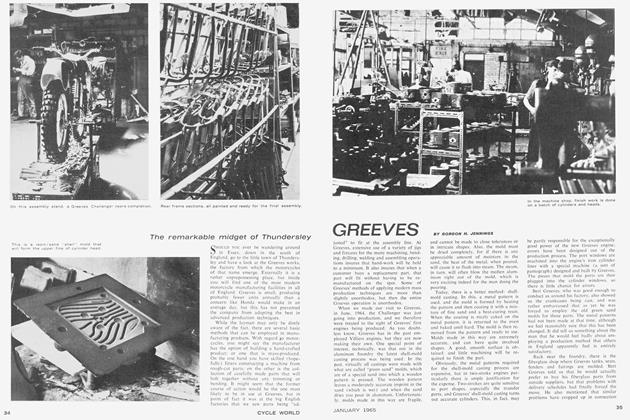

The most noticeable feature of the GPA-1 “Challenger” engine is the exceptionally deep finning on both its cylinder and cylinder head. The cylinder head looks a trifle peculiar due to the asymmetrical layout of its cooling fins, but while this may look wrong it functions right. Tests made have shown that air coming back past the front tire and frame “frontbone” does not want to circulate in toward the center of the head to cool the spark plug. To overcome this difficulty, the GPA-1 engine has its head fins arranged to funnel air toward the area of the spark plug. Also, if you look closely at the engine, you may notice that what appears to be the top fin on the cylinder is actually a part of the head casting. The purpose of this horizontal fin on the head is to carry heat away from the combustion chamber. The head is, incidentally, almost two full inches wider than that of the earlier engine.

Several of the design features of previous Greeves cylinders have been drastically changed in the GPA-1. Before, the fins were interrupted at each side of the transfer ports, on the theory that this would block heat flow to the port area and reduce heating of the charge. Also, the intake port was kept very short by cutting away the fins at the back of the cylinder, again in the interest of keeping heat from the incoming charge. In the new engine, the finning is continuous all around the cylinder, and a long intake port is cast right in. It is now felt that more will be gained by better cooling of the cylinder as a whole, and the consequently reduced distortion, than through any small reduction in mixture temperature.

There are two separate cylinders presently in production. One is for the Challenger scrambler; the other will be fitted on the new version of the Silverstone road racer. Both have a cast-in austenitic-iron sleeve with a .157 wall thickness. The austenitic iron has a coefficient of expansion very close to that of aluminum, which tends to reduce distortion and the sleeve is thick enough to further stabilize the shape of the bore. One point we should mention is that there are windows cut in the sleeve leading into the transfer ports as well as out of them. This leaves a continuous band of metal at the bottom of the cylinder, and that is yet another anti-distortion measure. We were told, at Greeves, that it is a mistake to remove the bar of iron under the lower transfer port window. Any increase in flow will be negligible, and the cylinder will be more likely to distort. The intake port on the scrambler cylinder has an 8-degree downdraft angle, and is 1-3/16" in diameter — to match the Monobloc carburetor. The road racing cylinder’s port is 1-3/8" in diameter, and angles down at 22-degrees. In both cases, the carburetor is separated from the cylinder by a pair of non-conducting packing pieces between which is sandwiched (on the scrambler) an aluminum heat shield or (on the road racer) the bracket for a remote-mounted float chamber.

The aluminum alloy crankcase is much sturdier than the old Villiers unit, both because the main bearings need the support and because the crankcase is now used as part of the frame. It houses an Alpha lower-end assembly, which has full-circle flywheels and an oval-section connecting rod. We are pleased to note that the outer race of the “big-end” rod bearing is a separate piece, pressed-in, as that means the running of a rod bearing will not be an occasion for replacing the entire rod. Two bearings, one ball and the other roller, are used on the drive-side mainshaft, while on the other side of the crank there is a single double-row roller bearing.

Spark for the Challenger engine is produced by a Swedish-made Stefa “energy-transfer” system. There is a very small (3-5/8" diameter) flywheel (containing 4 magnets) rotating around a single field coil and a breaker-point set. The ignition breaker cam is ground in the mainshaft. Lowtension current generated in the primary coil is led direct to ground until the points open (which they are timed to do when current is at full strength) and then it all hits the high-tension coil, which is mounted up on the motorcycle’s frame, and that in turn produces the spark.

With the new engine, Greeves is now using an Albion transmission and clutch. The transmission casing bolts solidly to the back of the engine crankcase, and is thus the next thing to being “unit-constructed.” Long extensions cast on the crankcase hold the transmission back away enough to allow a flow of cooling air on the back of the crankcase. The scrambler’s transmission is fitted with a 4-speed gearset, but those in the road racer will have 5 speeds.

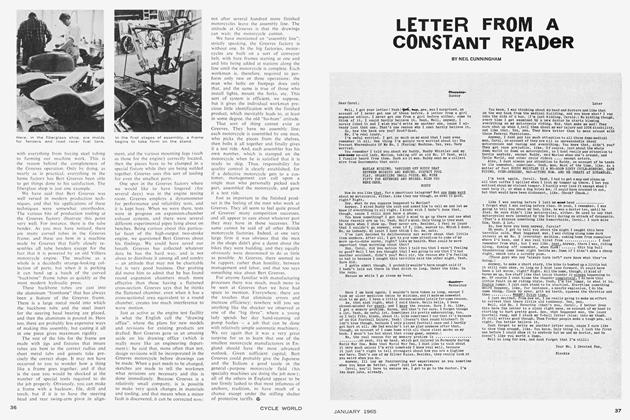

When the engine and transmission are bolted together, they are then used as a part of the frame. A pair of mounting plates fix the front of the crankcase to the lower end of the cast-aluminum frame member, and the back of the transmission bolts to brackets on the lower end of the frame’s backbone tube, thereby forming a bridge at the bottom of the frame. This measure provides a more rigid frame than before, and it has the additional benefit of giving more ground clearance. The added ground clearance has obvious usefulness on the scrambler, and it has given Greeves enough room for an improved expansionchamber exhaust system on the road racer. The scrambler also has an expansion chamber exhaust, but it is “tuned” more for torque than high engine speeds and pure horsepower. It is also somewhat less noisy than the old stub megaphone, which was much appreciated by our test crew.

To complement the new frame, Greeves have made detail changes in the scrambler's suspension, and while we have not been able to determine precisely what has been changed, the results tell us the changes have certainly been effective. As those of you who have ridden Greeves scramblers surely know, the previous model’s front forks would swing slowly back and forth when running at high speeds. In the Challenger this is entirely missing; it runs along at any speed without a sign of “hunting” at the front end. Fortunately, the old Greeves characteristic of having a front wheel that will at least try to climb over anything is still present. There may be lightweights that will equal the Greeves in rough going; there are none better.

The new fiberglass tank and fenders give the Challenger quite a different appearance: it now looks somehow more substantial; less spidery. At first glance the front fender seems too flimsy to survive much bashing around; you can push it around with your hand like so much starched cloth. However, here is the old story of the tree bending so as to avoid breaking, and that is precisely what the Challenger’s fender does. One of our crew became too enthusiastic, and dropped the machine in just the right spot to clout a rock with the front fender. Steel, aluminum or heavy fiberglass would have been permanently disarranged; the Challenger’s fender simply warped to one side and sprang back when the bike was lifted back on its wheels. In this, we may have also tested the Challenger’s handlebars, which are made of heat-treated spring steel, which will not take a permanent bend; they will pull away from the forks first.

For the first time, we had a Greeves on our hands that was an absolute snap to start. The Challenger is the first Greeves scrambler to be fitted with a choke, and this gave remarkably easy starting when cold. When hot, the engine needed no fussing at all: kick it a couple of times and it was running. We also noted with some pleasure that this latest Greeves, the first with an all-Greeves engine, had an even wider power band than the old models, and would take full throttle even at very low engine speeds without a cough.

When we totaled everything, we discovered that the only things about the Greeves Challenger that were less than a delight were the seat, which was a trifle thin and would “bottom” given the combination of a heavy rider and jolting terrain, and the transmission, which had a discouragingïy vague feeling. The shift lever has too much travel, and if you shift deliberately, it seems to fall through to the next gear. And, unfortunately, the travel at the lever feels the same whether the gear engages or not; not until you release the clutch do you know if the jab at the lever has accomplished anything. Try forcing shifts fast, and as often as not the transmission will stop in a neutral; there is room for improvement in this department.

While we did not care much for the Challenger’s transmission, the rest of the motorcycle made up for this single deficiency. It handles well, will run along at great speed over terrible terrain, had more power than before with an even wider power range and shows every promise of being even more reliable than any previous Greeves. We suppose it could be best described, for all of you Greeves’ enthusiasts out there, as “more of the same; but better.’ G

GREEVES CHALLENGER

SPECIFICATIONS

$875.00

POWER TRANSMISSION

DIMENSIONS, IN.

PER FORMANCE

ACCELERATION

View Full Issue

View Full Issue