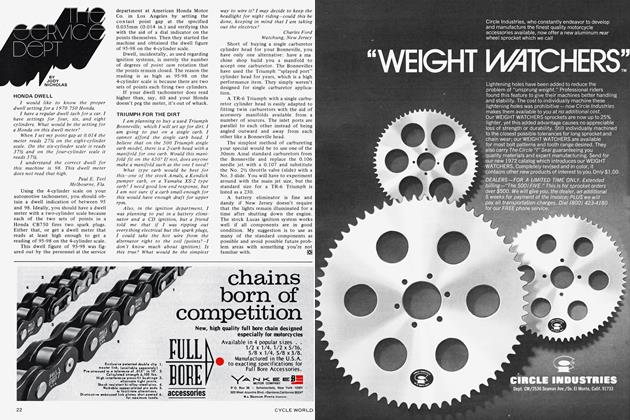

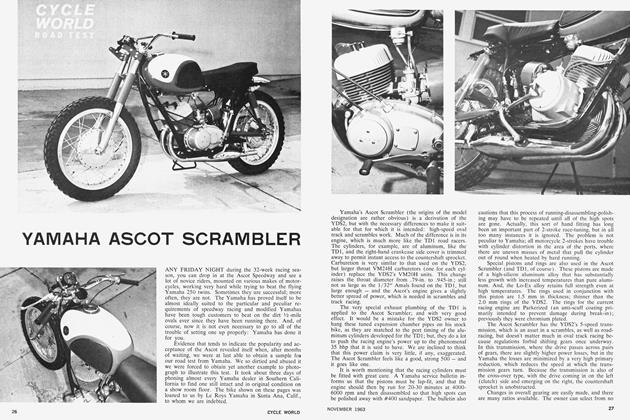

BULTACO SHERPA T350

Cycle World Road Test

It's A Bigger And Better Sherpa T

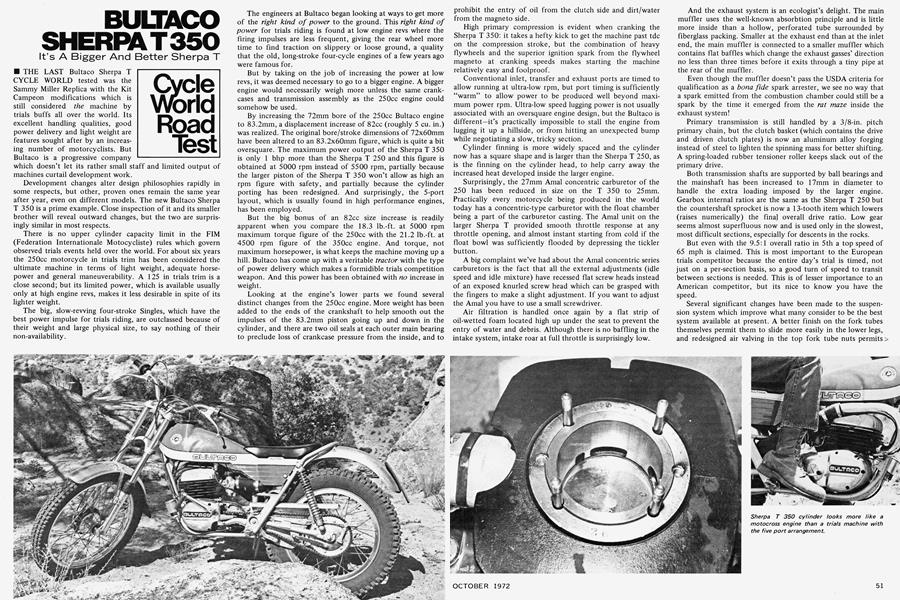

THE LAST Bultaco Sherpa T CYCLE WORLD tested was the Sammy Miller Replica with the Kit Campeon modifications which is still considered the machine by trials buffs all over the world. Its excellent handling qualities, good power delivery and light weight are features sought after by an increasing number of motorcyclists. But Bultaco is a progressive company which doesn't let its rather small staff and limited output of machines curtail development work.

Development changes alter design philosophies rapidly in some respects, but other, proven ones remain the same year after year, even on different models. The new Bultaco Sherpa T 350 is a prime example. Close inspection of it and its smaller brother will reveal outward changes, but the two are surprisingly similar in most respects.

There is no upper cylinder capacity limit in the FIM (Federation Internationale Motocycliste) rules which govern observed trials events held over the world. For about six years the 250cc motorcycle in trials trim has been considered the ultimate machine in terms of light weight, adequate horsepower and general maneuverability. A 125 in trials trim is a close second; but its limited power, which is available usually only at high engine revs, makes it less desirable in spite of its lighter weight.

The big, slow-revving four-stroke Singles, which have the best power impulse for trials riding, are outclassed because of their weight and large physical size, to say nothing of their non-availability.

The engineers at Bultaco began looking at ways to get more of the right kind of power to the ground. This right kind of power for trials riding is found at low engine revs where the firing impulses are less frequent, giving the rear wheel more time to find traction on slippery or loose ground, a quality that the old, long-stroke four-cycle engines of a few years ago were famous for.

But by taking on the job of increasing the power at low revs, it was deemed necessary to go to a bigger engine. A bigger engine would necessarily weigh more unless the same crankcases and transmission assembly as the 250cc engine could somehow be used.

By increasing the 72mm bore of the 250cc Bultaco engine to 83.2mm, a displacement increase of 82cc (roughly 5 cu. in.) was realized. The original bore/stroke dimensions of 72x60mm have been altered to an 83.2x60mm figure, which is quite a bit oversquare. The maximum power output of the Sherpa T 350 is only 1 bhp more than the Sherpa T 250 and this figure is obtained at 5000 rpm instead of 5500 rpm, partially because the larger piston of the Sherpa T 350 won’t allow as high an rpm figure with safety, and partially because the cylinder porting has been redesigned. And surprisingly, the 5-port layout, which is usually found in high performance engines, has been employed.

But the big bonus of an 82cc size increase is readily apparent when you compare the 18.3 lb.-ft. at 5000 rpm maximum torque figure of the 250cc with the 21.2 lb.-ft. at 4500 rpm figure of the 350cc engine. And torque, not maximum horsepower, is what keeps the machine moving up a hill. Bultaco has come up with a veritable tractor with the type of power delivery which makes a formidible trials competition weapon. And this power has been obtained with no increase in weight.

Looking at the engine’s lower parts we found several distinct changes from the 250cc engine. More weight has been added to the ends of the crankshaft to help smooth out the impulses of the 83.2mm piston going up and down in the cylinder, and there are two oil seals at each outer main bearing to preclude loss of crankcase pressure from the inside, and to prohibit the entry of oil from the clutch side and dirt/water from the magneto side.

High primary compression is evident when cranking the Sherpa T 350: it takes a hefty kick to get the machine past tdc on the compression stroke, but the combination of heavy flywheels and the superior ignition spark from the flywheel magneto at cranking speeds makes starting the machine relatively easy and foolproof.

Conventional inlet, transfer and exhaust ports are timed to allow running at ultra-low rpm, but port timing is sufficiently “warm” to allow power to be produced well beyond maximum power rpm. Ultra-low speed lugging power is not usually associated with an oversquare engine design, but the Bultaco is different—it’s practically impossible to stall the engine from lugging it up a hillside, or from hitting an unexpected bump while negotiating a slow, tricky section.

Cylinder finning is more widely spaced and the cylinder now has a square shape and is larger than the Sherpa T 250, as is the finning on the cylinder head, to help carry away the increased heat developed inside the larger engine.

Surprisingly, the 27mm Amal concentric carburetor of the 250 has been reduced in size on the T 350 to 25mm. Practically every motorcycle being produced in the world today has a concentric-type carburetor with the float chamber being a part of the carburetor casting. The Amal unit on the larger Sherpa T provided smooth throttle response at any throttle opening, and almost instant starting from cold if the float bowl was sufficiently flooded by depressing the tickler button.

A big complaint we’ve had about the Amal concentric series carburetors is the fact that all the external adjustments (idle speed and idle mixture) have recessed flat screw heads instead of an exposed knurled screw head which can be grasped with the fingers to make a slight adjustment. If you want to adjust the Amal you have to use a small screwdriver.

Air filtration is handled once again by a flat strip of oil-wetted foam located high up under the seat to prevent the entry of water and debris. Although there is no baffling in the intake system, intake roar at full throttle is surprisingly low.

And the exhaust system is an ecologist’s delight. The main muffler uses the well-known absorbtion principle and is little more inside than a hollow, perforated tube surrounded by fiberglass packing. Smaller at the exhaust end than at the inlet end, the main muffler is connected to a smaller muffler which contains flat baffles which change the exhaust gasses’ direction no less than three times before it exits through a tiny pipe at the rear of the muffler.

Even though the muffler doesn’t pass the USDA criteria for qualification as a bona fide spark arrester, we see no way that a spark emitted from the combustion chamber could still be a spark by the time it emerged from the rat maze inside the exhaust system!

Primary transmission is still handled by a 3/8-in. pitch primary chain, but the clutch basket (which contains the drive and driven clutch plates) is now an aluminum alloy forging instead of steel to lighten the spinning mass for better shifting.

A spring-loaded rubber tensioner roller keeps slack out of the primary drive.

Both transmission shafts are supported by ball bearings and the mainshaft has been increased to 17mm in diameter to handle the extra loading imposed by the larger engine. Gearbox internal ratios are the same as the Sherpa T 250 but the countershaft sprocket is now a 13-tooth item which lowers (raises numerically) the final overall drive ratio. Low gear seems almost superfluous now and is used only in the slowest, most difficult sections, especially for descents in the rocks.

But even with the 9.5:1 overall ratio in 5th a top speed of 65 mph is claimed. This is most important to the European trials competitor because the entire day’s trial is timed, not just on a per-section basis, so a good turn of speed to transit between sections is needed. This is of lesser importance to an American competitor, but its nice to know you have the speed.

Several significant changes have been made to the suspension system which improve what many consider to be the best system available at present. A better finish on the fork tubes themselves permit them to slide more easily in the lower legs, and redesigned air valving in the top fork tube nuts permits smoother operation of the forks because the air trapped inside now only has to overcome a flapper valve to escape rather than unseat a check ball and compress a spring.

In order to increase the rigidity of the front fork assembly the forged aluminum lower triple-clamp is arch-shaped and contains strengthening ribs. This arch-shaping increases the distance between it and the top triple-clamp. It also shortens the distance from the axle to the lower fork clamp and thus makes for a more rigid fork assembly. The front forks offer 6.5 in. of travel. The small diameter rear suspension units, which are also manufactured to Bultaco specifications by Betor, feature a three-way spring adjustment and a tiny bit less than 4 in. of travel.

The rear shocks’ damping is not adjustable but seemed spot on to all our staff members. Damping, and to a lesser extent compression resistance of the front forks, may be altered by the substitution of different viscosity oils.

The brakes on a trials or motocross machine are much smaller than, say, a road machine or a road racer, but are in every way just as important. The Sherpa T 350 front brake hub is a tiny affair which features an aluminum hub with the brake band being steel which is deposited on the aluminum by an electrolytic process. Because a great amount of heat is not developed in stopping a lightweight trials machine from low speeds there is really no sense in having a shrunk-in steel brake liner to add unnecessary unsprung weight to the machine. The complete front wheel assembly, without the tire, weighs a mere 8.5 lb.!

The proven rear brake assembly of the Sherpa T 250 is used on the larger machine and has the same outstanding feel and control. The rear brake pedal end is a circular ring which is saw-toothed on the top edge and hollow in the center to allow mud from the rider’s left boot to fall back to the ground.

The rear chain features a spring-loaded tensioner to keep it

moving smoothly between the sprockets, to preclude its becoming derailed by branches and to remove any slack in the drive system. When the rider wants a tiny bit of power, or a little less power, he can obtain either by judicious throttle control without having to wait for the slack of the two chains to be taken up. Trials riding requires a great amount of finesse, but the Sherpa T makes it easier to be graceful!

One of the nice little touches on a Bultaco trialer is its rear chain oiler in the left hand swinging arm leg. A small quantity of oil placed in the hollow leg is delivered to the rear chain through an adjustable feed needle and a plastic tube.

The strong double cradle frame is a duplicate of the Sherpa T 250 and is characterized by adequate steel plate bracing at points of stress and a bash plate to protect the underside of the engine which is welded between the bottom horizontal frame tubes.

The appearance and functionality of Spanish machinery has made great strides in the past few years. Fiberglass work is smooth and well finished, the welding on the frames is getting smoother and more attractive, and the cast aluminum clutch and front brake levers are exquisite in detail and functionality. And besides being aesthetically beautiful, the ultra-narrow one-piece seat/gas tank is designed to allow the rider to keep his knees together, or to clamber about keeping his balance.

About the only thing we could find to complain about were the tires which came fitted to the machine—they were motocross pattern knobbies. The first thing we did was fit Dunlop trials universal tires. Then we fired the machine up and had several of the most exciting rides imaginable. In spite of some skepticism about the 350 (actually 326cc) engine being the way to go for trials competition, we feel that once the hardened trials buffs get used to the additional power they will like it. And we feel sure the novices will get a charge out of owning a machine that will climb almost anything!

BULTACO SHERPA T 350

SPECIFICATIONS

$1049

POWER TRANSMISSION

DIMENSIONS