A FUTURE FOR DIRT TRACK?

IGNITION

TDC

FABULOUS TRAINING GROUND DESERVES BETTER

KEVIN CAMERON

When US dirt-track star Brad Baker defeated MotoGP World Champion Marc Marquez in the Spanish Superprestigio indoor short-track event last December, people paid attention. Why? First of all, enthusiasts could see the show streamed live on fanschoice.tv, thanks to last-minute arrangements. Secondly, dirt track suddenly was in the spotlight as a seething hotbed of talent.

Whatever became of the oncedynamic AMA Grand National Championship and of the central role of flat track within it? When the late, great Gary Nixon was winning that title, riders needed points won in all its disciplines—mile and half-mile flat track, roadrace, and TT.

What happened was that motocross and roadracing established themselves as major attractions in their own right, and the British manufacturers who had given Harley such a run for its money since WWII sickened and died after 1972.

Yet dirt racing had been a wellspring of talent and technical innovation. Through the 1950s and ’60s, California’s Ascot half-mile had been America’s University of Speed, a hot nucleus spitting out top riders and innovative builders. Those days offered none of the plane tickets, motorhomes, or airconditioned team transporters of today. Those were battles of men who carried everything they needed in the backs of pickup trucks and drove pre-interstate two-laners to wherever the most money was up for grabs. My former rider Ron Pierce described being able to pick up an easy $300 a night at smaller dirt tracks around Southern California in the late 1960s. Dick Mann was a dirttrack gypsy, equipment in the back of his pickup, traveling with a younger hopeful as student and co-earner. Mann himself had learned from mentor and

innovator Albert Gunter. Hungry? Need a piston for the Gold Star? Gas for the truck? Prize money was the only money. Injured? To eat, you gotta race, so out comes a saw to cut off the plaster and get on with the program.

After 1970, the dirt-track-centered AMA Grand National Championship hit competition. Bultaco in the late 1960s revealed the market for light, cheap two-stroke off-road bikes, and when the Japanese saw that, motocross established itself as the new, true path to stardom and high income on two wheels. AMA’s accidental success in creating a 750 roadrace class in 1972 created another route to factory rides and world status. Big things were happening—and not at the fairgrounds.

The collapse of British brands ended the once-dynamic 1950s and ’60s scene, leaving only Harley and Yamaha. Dirt track was now coasting on its history. The series continued and great names emerged, but it had become a small pond, far from the great ocean.

Since then, the AMA has put forth at least six initiatives to revitalize dirt track—to make cheaper bikes available and to interest young people in flat-track racing. Kenny Roberts did his best on Yamaha’s XSóso-based bikes but drove a stake into the heart of tradition by winning the 1975 Indianapolis Mile on a thoroughly frightening Yamaha TZ750A two-stroke. Erv Kanemoto fielded a close-firing-order version of Kawasaki’s 750 H2 triple, and the speed and threat of these two-strokes panicked the AMA into banning them from dirt track at the end of that season.

The next interruption came from Honda, as a cooperative project between the company, rider/promoter Gene Romero, cam engineer Jim Dour, and machinist/engineer Dave Ijams. When the resulting Honda RS750 eventually won races, a second shock wave of AMA

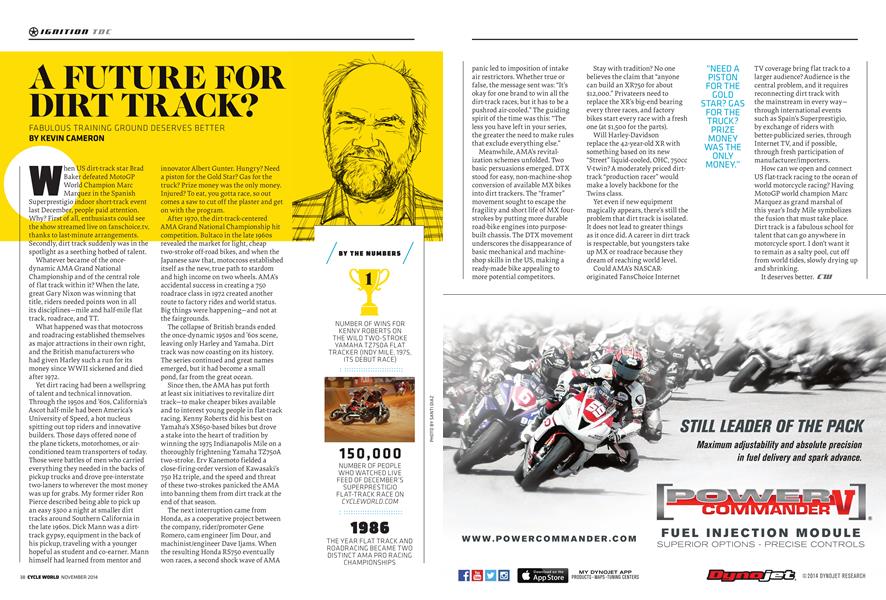

BY THE NUMBERS

NUMBER OF WINS FOR KENNY ROBERTS ON THE WILD TWO-STROKE YAMAHA TZ7SOA FLAT TRACIKER (INDY MILE, 1975, ITS DEBUT RACE)

150,000 NUMBER OF PEOPLE WHO WATCHED LIVE FEED OF DECEMBER'S SUPERPRESTIGIO FLAT-TRACK RACE ON CYCLEWORLD.COM

1986 THE YEAR FLAT TRACK AND ROADRACING BECAME TWO DISTINCT AMA PRO RACING CHAMPIONSHIPS

panic led to imposition of intake air restrictors. Whether true or false, the message sent was: “It’s okay for one brand to win all the dirt-track races, but it has to be a pushrod air-cooled.” The guiding spirit of the time was this: “The less you have left in your series, the greater the need to make rules that exclude everything else.” Meanwhile, AMA’s revitalization schemes unfolded. Two basic persuasions emerged. DTX stood for easy, non-machine-shop conversion of available MX bikes into dirt trackers. The “framer” movement sought to escape the fragility and short life of MX fourstrokes by putting more durable road-bike engines into purposebuilt chassis. The DTX movement underscores the disappearance of basic mechanical and machineshop skills in the US, making a ready-made bike appealing to more potential competitors.

Stay with tradition? No one believes the claim that “anyone can build an XR750 for about $12,000.” Privateers need to replace the XR’s big-end bearing every three races, and factory bikes start every race with a fresh one (at $1,500 for the parts).

Will Harley-Davidson replace the 42-year-old XR with something based on its new “Street” liquid-cooled, OHC, 75OCC V-twin? A moderately priced dirttrack “production racer” would make a lovely backbone for the Twins class.

Yet even if new equipment magically appears, there’s still the problem that dirt track is isolated. It does not lead to greater things as it once did. A career in dirt track is respectable, but youngsters take up MX or roadrace because they dream of reaching world level.

Could AMA’s NASCARoriginated FansChoice Internet

TV coverage bring flat track to a larger audience? Audience is the central problem, and it requires reconnecting dirt track with the mainstream in every waythrough international events such as Spain’s Superprestigio, by exchange of riders with better-publicized series, through Internet TV, and if possible, through fresh participation of manufacturer/importers.

How can we open and connect US flat-track racing to the ocean of world motorcycle racing? Having MotoGP world champion Marc Marquez as grand marshal of this year’s Indy Mile symbolizes the fusion that must take place. Dirt track is a fabulous school for talent that can go anywhere in motorcycle sport. I don’t want it to remain as a salty pool, cut off from world tides, slowly drying up and shrinking.

It deserves better. E1U

“NEED A PISTON FOR THE GOLD STAR? GAS FOR THE TRUCK? PRIZE MONEY WAS THE ONLY MONEY.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Golden Cage

November 2014 By Mark Hoyer -

Intake

IntakeIntake

November 2014 -

Ignition

IgnitionBattery Basics

November 2014 By Kevin Cameron -

Ignition

IgnitionThe Kinetic Art of Marc Marquez

November 2014 By Milagro, Tino Martino -

Ignition

IgnitionCw 25 Years Ago November 1989

November 2014 By Mark Hoyer -

Ignition

IgnitionSidi Insider Shoe

November 2014